| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | NEW RESEARCH: The horrific realities of giving birth in jail |

| Date | July 1, 2025 2:53 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Little data exists about the experience of giving birth in jail. What we do know is horrifying.

Prison Policy Initiative updates for July 1, 2025 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Birth behind bars: Ten years of U.S. jail births covered in the news highlight horrific experiences and minimal data collection [[link removed]] For some of the thousands of pregnant people entering jails each year, at what might be their moment of greatest need — going into labor — jails turn a blind eye, harming mothers, newborns, and their families. [[link removed]]

by Leah Wang and Bianca Schindeler

In the confines of an unsanitary jail cell, a woman delivers a baby alone: This is a typical news article about a jail birth. But when it comes to the 1.5 million women cycling through jails [[link removed]] each year, what more do experts know about jail births on a larger scale? The answer: Nothing — there is no regular data collection on pregnant or postpartum people held in local jails. (As for those in prisons, there is some limited data collection.)

Given the lack of transparency from jails about pregnancies, birth outcomes, and other facets of reproductive care, a team of student researchers is drawing attention to this data blind spot. The Birth in Jails Media Project, which draws entirely from local news coverage of jail births, provides a rich picture of how some pregnant people experience incarceration, labor, and childbirth, with more detail about jail conditions and staff responses than a national dataset can typically provide.

In this briefing, we present the first-ever published findings from the Birth in Jails Media Project, one of many indispensable efforts from Advocacy and Research on Reproductive Wellness of Incarcerated People [[link removed]] (ARRWIP), a reproductive justice-oriented research group at John Hopkins University led by researcher and obstetrician-gynecologist Dr. Carolyn Sufrin. (We’ve previously lifted up [[link removed]] ARRWIP’s important work [[link removed]] on contraception, abortion, breastfeeding, and medication for opioid use disorder policies for pregnant women in custody.)

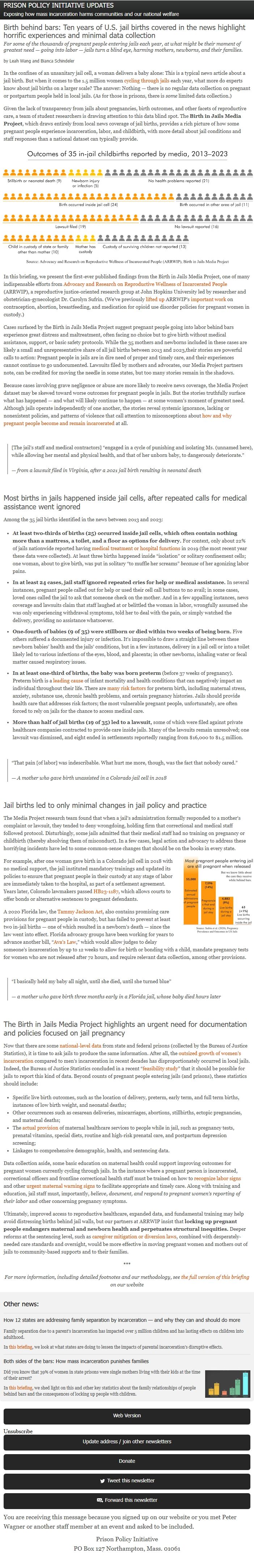

Cases surfaced by the Birth in Jails Media Project suggest pregnant people going into labor behind bars experience great distress and maltreatment, often facing no choice but to give birth without medical assistance, support, or basic safety protocols. While the 35 mothers and newborns included in these cases are likely a small and unrepresentative share of all jail births between 2013 and 2023,their stories are powerful calls to action: Pregnant people in jails are in dire need of proper and timely care, and their experiences cannot continue to go undocumented. Lawsuits filed by mothers and advocates, our Media Project partners note, can be credited for moving the needle in some states, but too many stories remain in the shadows.

Because cases involving grave negligence or abuse are more likely to receive news coverage, the Media Project dataset may be skewed toward worse outcomes for pregnant people in jails. But the stories truthfully surface what has happened — and what will likely continue to happen — at some women’s moment of greatest need. Although jails operate independently of one another, the stories reveal systemic ignorance, lacking or nonexistent policies, and patterns of violence that call attention to misconceptions about how and why pregnant people become and remain incarcerated [[link removed]] at all.

[The jail’s staff and medical contractors] “engaged in a cycle of punishing and isolating Ms. (unnamed here), while allowing her mental and physical health, and that of her unborn baby, to dangerously deteriorate.”

— from a lawsuit filed in Virginia, after a 2021 jail birth resulting in neonatal death

Most births in jails happened inside jail cells, after repeated calls for medical assistance went ignored

Among the 35 jail births identified in the news between 2013 and 2023:

At least two-thirds of births (25) occurred inside jail cells, which often contain nothing more than a mattress, a toilet, and a floor as options for delivery. For context, only about 22% of jails nationwide reported having medical treatment or hospital functions [[link removed]] in 2019 (the most recent year these data were collected). At least three births happened inside “isolation” or solitary confinement cells; one woman, about to give birth, was put in solitary “to muffle her screams” because of her agonizing labor pains. In at least 24 cases, jail staff ignored repeated cries for help or medical assistance. In several instances, pregnant people called out for help or used their cell call buttons to no avail; in some cases, loved ones called the jail to ask that someone check on the mother. And in a few appalling instances, news coverage and lawsuits claim that staff laughed at or belittled the woman in labor, wrongfully assumed she was only experiencing withdrawal symptoms, told her to deal with the pain, or simply watched the delivery, providing no assistance whatsoever. One-fourth of babies (9 of 35) were stillborn or died within two weeks of being born. Five others suffered a documented injury or infection. It’s impossible to draw a straight line between these newborn babies’ health and the jails’ conditions, but in a few instances, delivery in a jail cell or into a toilet likely led to various infections of the eyes, blood, and placenta; in other newborns, inhaling water or fecal matter caused respiratory issues. In at least one-third of births, the baby was born preterm (before 37 weeks of pregnancy). Preterm birth is a leading cause [[link removed]] of infant mortality and health conditions that can negatively impact an individual throughout their life. There are many risk factors [[link removed]] for preterm birth, including maternal stress, anxiety, substance use, chronic health problems, and certain pregnancy histories. Jails should provide health care that addresses risk factors; the most vulnerable pregnant people, unfortunately, are often forced to rely on jails for the chance to access medical care. More than half of jail births (19 of 35) led to a lawsuit, some of which were filed against private healthcare companies contracted to provide care inside jails. Many of the lawsuits remain unresolved; one lawsuit was dismissed, and eight ended in settlements reportedly ranging from $16,000 to $1.5 million.

“That pain [of labor] was indescribable. What hurt me more, though, was the fact that nobody cared.”

— A mother who gave birth unassisted in a Colorado jail cell in 2018

Jail births led to only minimal changes in jail policy and practice

The Media Project research team found that when a jail’s administration formally responded to a mother’s complaint or lawsuit, they tended to deny wrongdoing, holding firm that correctional and medical staff followed protocol. Disturbingly, some jails admitted that their medical staff had no training on pregnancy or childbirth (thereby absolving them of misconduct). In a few cases, legal action and advocacy to address these horrifying incidents have led to some common-sense changes that should be on the books in every state.

For example, after one woman gave birth in a Colorado jail cell in 2018 with no medical support, the jail instituted mandatory trainings and updated its policies to ensure that pregnant people in their custody at any stage of labor are immediately taken to the hospital, as part of a settlement agreement. Years later, Colorado lawmakers passed HB23-1187 [[link removed]], which allows courts to offer bonds or alternative sentences to pregnant defendants.

A 2020 Florida law, the Tammy Jackson Act [[link removed]], also contains promising care provisions for pregnant people in custody, but has failed to prevent at least two in-jail births — one of which resulted in a newborn’s death — since the law went into effect. Florida advocacy groups have been working for years to advance another bill, “ Ava’s Law [[link removed]],” which would allow judges to delay someone’s incarceration by up to 12 weeks to allow for birth or bonding with a child, mandate pregnancy tests for women who are not released after 72 hours, and require relevant data collection, among other provisions.

“I basically held my baby all night, until she died, until she turned blue”

— a mother who gave birth three months early in a Florida jail, whose baby died hours later

The Birth in Jails Media Project highlights an urgent need for documentation and policies focused on jail pregnancy

Now that there are some national-level data [[link removed]] from state and federal prisons (collected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics), it is time to ask jails to produce the same information. After all, the outsized growth of women’s incarceration [[link removed]] compared to men’s incarceration in recent decades has disproportionately occurred in local jails. Indeed, the Bureau of Justice Statistics concluded in a recent “ feasibility study [[link removed]]” that it should be possible for jails to report this kind of data. Beyond counts of pregnant people entering jails (and prisons), these statistics should include:

Specific live birth outcomes, such as the location of delivery, preterm, early term, and full term births, instances of low birth weight, and neonatal deaths; Other occurrences such as cesarean deliveries, miscarriages, abortions, stillbirths, ectopic pregnancies, and maternal deaths; The actual provision [[link removed]] of maternal healthcare services to people while in jail, such as pregnancy tests, prenatal vitamins, special diets, routine and high-risk prenatal care, and postpartum depression screening; Linkages to comprehensive demographic, health, and sentencing data.

Data collection aside, some basic education on maternal health could support improving outcomes for pregnant women currently cycling through jails. In the instance where a pregnant person is incarcerated, correctional officers and frontline correctional health staff must be trained on how to recognize labor signs [[link removed]] and other urgent maternal warning signs [[link removed]] to facilitate appropriate and timely care. Along with training and education, jail staff must, importantly, believe, document, and respond to pregnant women’s reporting of their labor and other concerning pregnancy symptoms.

Ultimately, improved access to reproductive healthcare, expanded data, and fundamental training may help avoid distressing births behind jail walls, but our partners at ARRWIP insist that locking up pregnant people endangers maternal and newborn health and perpetuates structural inequities. Deeper reforms at the sentencing level, such as caregiver mitigation or diversion laws [[link removed]], combined with desperately-needed care standards and oversight, would be more effective in moving pregnant women and mothers out of jails to community-based supports and to their families.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes and our methodology, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: How 12 states are addressing family separation by incarceration — and why they can and should do more [[link removed]]

Family separation due to a parent’s incarceration has impacted over 5 million children and has lasting effects on children into adulthood.

In this briefing [[link removed]], we look at what states are doing to lessen the impacts of parental incarceration's disruptive effects.

Both sides of the bars: How mass incarceration punishes families [[link removed]]

Did you know that 39% of women in state prisons were single mothers living with their kids at the time of their arrest?

In this briefing [[link removed]], we shed light on this and other key statistics about the family relationships of people behind bars and the consequences of locking up people with children.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for July 1, 2025 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Birth behind bars: Ten years of U.S. jail births covered in the news highlight horrific experiences and minimal data collection [[link removed]] For some of the thousands of pregnant people entering jails each year, at what might be their moment of greatest need — going into labor — jails turn a blind eye, harming mothers, newborns, and their families. [[link removed]]

by Leah Wang and Bianca Schindeler

In the confines of an unsanitary jail cell, a woman delivers a baby alone: This is a typical news article about a jail birth. But when it comes to the 1.5 million women cycling through jails [[link removed]] each year, what more do experts know about jail births on a larger scale? The answer: Nothing — there is no regular data collection on pregnant or postpartum people held in local jails. (As for those in prisons, there is some limited data collection.)

Given the lack of transparency from jails about pregnancies, birth outcomes, and other facets of reproductive care, a team of student researchers is drawing attention to this data blind spot. The Birth in Jails Media Project, which draws entirely from local news coverage of jail births, provides a rich picture of how some pregnant people experience incarceration, labor, and childbirth, with more detail about jail conditions and staff responses than a national dataset can typically provide.

In this briefing, we present the first-ever published findings from the Birth in Jails Media Project, one of many indispensable efforts from Advocacy and Research on Reproductive Wellness of Incarcerated People [[link removed]] (ARRWIP), a reproductive justice-oriented research group at John Hopkins University led by researcher and obstetrician-gynecologist Dr. Carolyn Sufrin. (We’ve previously lifted up [[link removed]] ARRWIP’s important work [[link removed]] on contraception, abortion, breastfeeding, and medication for opioid use disorder policies for pregnant women in custody.)

Cases surfaced by the Birth in Jails Media Project suggest pregnant people going into labor behind bars experience great distress and maltreatment, often facing no choice but to give birth without medical assistance, support, or basic safety protocols. While the 35 mothers and newborns included in these cases are likely a small and unrepresentative share of all jail births between 2013 and 2023,their stories are powerful calls to action: Pregnant people in jails are in dire need of proper and timely care, and their experiences cannot continue to go undocumented. Lawsuits filed by mothers and advocates, our Media Project partners note, can be credited for moving the needle in some states, but too many stories remain in the shadows.

Because cases involving grave negligence or abuse are more likely to receive news coverage, the Media Project dataset may be skewed toward worse outcomes for pregnant people in jails. But the stories truthfully surface what has happened — and what will likely continue to happen — at some women’s moment of greatest need. Although jails operate independently of one another, the stories reveal systemic ignorance, lacking or nonexistent policies, and patterns of violence that call attention to misconceptions about how and why pregnant people become and remain incarcerated [[link removed]] at all.

[The jail’s staff and medical contractors] “engaged in a cycle of punishing and isolating Ms. (unnamed here), while allowing her mental and physical health, and that of her unborn baby, to dangerously deteriorate.”

— from a lawsuit filed in Virginia, after a 2021 jail birth resulting in neonatal death

Most births in jails happened inside jail cells, after repeated calls for medical assistance went ignored

Among the 35 jail births identified in the news between 2013 and 2023:

At least two-thirds of births (25) occurred inside jail cells, which often contain nothing more than a mattress, a toilet, and a floor as options for delivery. For context, only about 22% of jails nationwide reported having medical treatment or hospital functions [[link removed]] in 2019 (the most recent year these data were collected). At least three births happened inside “isolation” or solitary confinement cells; one woman, about to give birth, was put in solitary “to muffle her screams” because of her agonizing labor pains. In at least 24 cases, jail staff ignored repeated cries for help or medical assistance. In several instances, pregnant people called out for help or used their cell call buttons to no avail; in some cases, loved ones called the jail to ask that someone check on the mother. And in a few appalling instances, news coverage and lawsuits claim that staff laughed at or belittled the woman in labor, wrongfully assumed she was only experiencing withdrawal symptoms, told her to deal with the pain, or simply watched the delivery, providing no assistance whatsoever. One-fourth of babies (9 of 35) were stillborn or died within two weeks of being born. Five others suffered a documented injury or infection. It’s impossible to draw a straight line between these newborn babies’ health and the jails’ conditions, but in a few instances, delivery in a jail cell or into a toilet likely led to various infections of the eyes, blood, and placenta; in other newborns, inhaling water or fecal matter caused respiratory issues. In at least one-third of births, the baby was born preterm (before 37 weeks of pregnancy). Preterm birth is a leading cause [[link removed]] of infant mortality and health conditions that can negatively impact an individual throughout their life. There are many risk factors [[link removed]] for preterm birth, including maternal stress, anxiety, substance use, chronic health problems, and certain pregnancy histories. Jails should provide health care that addresses risk factors; the most vulnerable pregnant people, unfortunately, are often forced to rely on jails for the chance to access medical care. More than half of jail births (19 of 35) led to a lawsuit, some of which were filed against private healthcare companies contracted to provide care inside jails. Many of the lawsuits remain unresolved; one lawsuit was dismissed, and eight ended in settlements reportedly ranging from $16,000 to $1.5 million.

“That pain [of labor] was indescribable. What hurt me more, though, was the fact that nobody cared.”

— A mother who gave birth unassisted in a Colorado jail cell in 2018

Jail births led to only minimal changes in jail policy and practice

The Media Project research team found that when a jail’s administration formally responded to a mother’s complaint or lawsuit, they tended to deny wrongdoing, holding firm that correctional and medical staff followed protocol. Disturbingly, some jails admitted that their medical staff had no training on pregnancy or childbirth (thereby absolving them of misconduct). In a few cases, legal action and advocacy to address these horrifying incidents have led to some common-sense changes that should be on the books in every state.

For example, after one woman gave birth in a Colorado jail cell in 2018 with no medical support, the jail instituted mandatory trainings and updated its policies to ensure that pregnant people in their custody at any stage of labor are immediately taken to the hospital, as part of a settlement agreement. Years later, Colorado lawmakers passed HB23-1187 [[link removed]], which allows courts to offer bonds or alternative sentences to pregnant defendants.

A 2020 Florida law, the Tammy Jackson Act [[link removed]], also contains promising care provisions for pregnant people in custody, but has failed to prevent at least two in-jail births — one of which resulted in a newborn’s death — since the law went into effect. Florida advocacy groups have been working for years to advance another bill, “ Ava’s Law [[link removed]],” which would allow judges to delay someone’s incarceration by up to 12 weeks to allow for birth or bonding with a child, mandate pregnancy tests for women who are not released after 72 hours, and require relevant data collection, among other provisions.

“I basically held my baby all night, until she died, until she turned blue”

— a mother who gave birth three months early in a Florida jail, whose baby died hours later

The Birth in Jails Media Project highlights an urgent need for documentation and policies focused on jail pregnancy

Now that there are some national-level data [[link removed]] from state and federal prisons (collected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics), it is time to ask jails to produce the same information. After all, the outsized growth of women’s incarceration [[link removed]] compared to men’s incarceration in recent decades has disproportionately occurred in local jails. Indeed, the Bureau of Justice Statistics concluded in a recent “ feasibility study [[link removed]]” that it should be possible for jails to report this kind of data. Beyond counts of pregnant people entering jails (and prisons), these statistics should include:

Specific live birth outcomes, such as the location of delivery, preterm, early term, and full term births, instances of low birth weight, and neonatal deaths; Other occurrences such as cesarean deliveries, miscarriages, abortions, stillbirths, ectopic pregnancies, and maternal deaths; The actual provision [[link removed]] of maternal healthcare services to people while in jail, such as pregnancy tests, prenatal vitamins, special diets, routine and high-risk prenatal care, and postpartum depression screening; Linkages to comprehensive demographic, health, and sentencing data.

Data collection aside, some basic education on maternal health could support improving outcomes for pregnant women currently cycling through jails. In the instance where a pregnant person is incarcerated, correctional officers and frontline correctional health staff must be trained on how to recognize labor signs [[link removed]] and other urgent maternal warning signs [[link removed]] to facilitate appropriate and timely care. Along with training and education, jail staff must, importantly, believe, document, and respond to pregnant women’s reporting of their labor and other concerning pregnancy symptoms.

Ultimately, improved access to reproductive healthcare, expanded data, and fundamental training may help avoid distressing births behind jail walls, but our partners at ARRWIP insist that locking up pregnant people endangers maternal and newborn health and perpetuates structural inequities. Deeper reforms at the sentencing level, such as caregiver mitigation or diversion laws [[link removed]], combined with desperately-needed care standards and oversight, would be more effective in moving pregnant women and mothers out of jails to community-based supports and to their families.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes and our methodology, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: How 12 states are addressing family separation by incarceration — and why they can and should do more [[link removed]]

Family separation due to a parent’s incarceration has impacted over 5 million children and has lasting effects on children into adulthood.

In this briefing [[link removed]], we look at what states are doing to lessen the impacts of parental incarceration's disruptive effects.

Both sides of the bars: How mass incarceration punishes families [[link removed]]

Did you know that 39% of women in state prisons were single mothers living with their kids at the time of their arrest?

In this briefing [[link removed]], we shed light on this and other key statistics about the family relationships of people behind bars and the consequences of locking up people with children.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor