|

Vaccines on offense

The anti-vaccination movement is dangerously effective. Time for science to go on offense.

Even with today’s endless cavalcade of corruption and bad policy, it’s impossible to get angry about everything. You’ll lose your mind.¹

It’s fine—and justified—to be angry. But I encourage people to focus on one or two things, because that’s the most impactful way to channel your energy.

For me, one of those issues: vaccines. The anti-vaccination movement is a moral and scientific outrage; people, children especially, are needlessly suffering and dying. That’s tragically on display in West Texas.

Sanity is losing right now. The science and pro-vaccine communities—that is to say, the people who are correct—are not doing a good job presenting their case. The anti-vaccine people are gaining ground because they’re running a campaign on fear.

It’s time to aggressively fight back.

The miracle of vaccines

This should go without saying but I’ll say it anyway: vaccines are miracles. They’re an absolute scientific wonder; the eradication of smallpox is arguably the most extraordinary accomplishment in the history of human civilization.²

Polio, measles, and rubella had all been eliminated in the U.S. The death rate from infectious diseases has been in decline for decades, even with a recent COVID spike.

We slayed one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.³ And now, for no good reason, Bobby Kennedy, Jr. and the Trump Administration are bringing that Horseman back to life.

The dangerously effective anti-vaccine movement

I mean this sincerely: Bobby Kennedy, Jr. is one of the worst people in America.⁴ But he’s not dumb, at least in the sense that he knows how to get his (wrong and dangerous) message out there. Skepticism around vaccines is as high as it’s been on record.⁵

Why? Some of this is a function of people with platforms spreading misinformation: Bobby Kennedy, Jr., Tucker Carlson, Ron Johnson, Marianne Williamson, and others.⁶ And some of this is a function of silos on social media: people who consume diverse media are much likelier to get vaccinated.

But a lot of this comes down to the power of fear.

Fear is a powerful—and lopsided—motivator

On July 29, 1944, my great-grandfather Leon wrote my grandmother Kit a letter. She was 12 years old and away at summer camp.

Leon was a collegiate swimmer and he’d stuck with the hobby for decades. But when he wrote the letter, he hadn’t gone swimming in over a month. Why? An outbreak of “Infantile,” shorthand for infantile paralysis—a disease we know today as polio.

“We are glad that you didn’t go to North Carolina,” my great-grandfather wrote in that letter, “because there are one thousand cases of Infantile in that state.”

A family friend, who grew up in St. Louis and recently turned 100, mentioned a few years ago that several of her elementary-school classmates spent time in iron lungs. Children and parents lived in fear of the iron lung for decades; they don’t anymore.⁷

|

What do parents fear today? Well, too many fear things that are patently untrue: that vaccines cause autism (false) or that they alter your DNA (false) or that they infect you with diseases (false) or that they contain microchips to track or control you (false).

But these are all real narratives, that real people—people trying to make the best, if misinformed, decisions for their children—believe. Their information is wrong but their fear is genuine.

The average age of a mom giving birth in the U.S. today is about 30 years old. That means that she was born in 1995, decades after the eradication of yellow fever, smallpox, and polio in the U.S.

She’s never experienced the fear that my grandmother and great-grandfather felt. As I’ve talked about before, when it comes to vaccines, we’re victims of our own success. But we need to make people fear these diseases, because they’re worth fearing.

Gaines County, Texas—the epicenter of the recent measles outbreak—has one of the lowest measles vaccination rates in the country.⁸ But even in Gaines County—where there’s demonstrable skepticism around vaccines—there’s been a spike in the number of children getting vaccinated.

Why? Fear is a powerful motivator, especially when the devil is on your doorstep.

Scientists: great at saving lives, bad at marketing

People should fear measles, fear polio, fear rubella, and fear other diseases. But scientists aren’t conveying that message particularly well. Take a look at the CDC’s websites for measles and polio.⁹

Factual? Yes. But these websites are also boring, and I sincerely doubt they’re changing anyone’s mind. On top of that, only 59% of Americans say that they trust the CDC,¹⁰ so they’re starting from behind.

COVID-19 was a vicious disease. But it wasn’t visually gruesome in the way that polio and measles are.

The pro-science people are often too in the weeds and too lost in the data. We need to deploy some of the same tactics of fear that have been so successful for the anti-vaccination crusaders.

This is what smallpox, polio, and measles look like. They were painful and unspeakably horrible diseases that, in many cases, hit children hardest. When you talk about this stuff—on social media, with vaccine skeptical friends and family—you need to remind people how terrible these afflictions were. We can start to do that by sharing pictures and stories more broadly than anything I’m seeing.

|

|

But it goes beyond that. Remember the panic at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic?

That baseline level of panic, fear, and paranoia was a way of life—except these diseases are much likelier to kill children, and they were around much more consistently.

Here’s a quote from David Oshinsky, a historian who wrote Polio: An American Story and lived through polio epidemics himself. (Emphasis added.)

The public was horribly and understandably frightened by polio. There was no prevention and no cure. Everyone was at risk, especially children. There was nothing a parent could do to protect the family. I grew up in this era. Each summer, polio would come like The Plague. Beaches and pools would close — because of the fear that the poliovirus was waterborne. Children had to stay away from crowds, so they often were banned from movie theaters, bowling alleys, and the like. My mother gave us all a ‘polio test’ each day: Could we touch our toes and put our chins to our chest? Every stomach ache or stiffness caused a panic. Was it polio? I remember the awful photos of children on crutches, in wheelchairs and iron lungs. And coming back to school in September to see the empty desks where the children hadn't returned.

We do not need to live with this level of fear—the success of vaccines is that we don’t have to live that way. But we do need to remind people that all of this is just around the corner.

More assertively sharing these photos and stories is one way to do that.

All of this is pretty heavy, so I’ll close this section with Police Chief Wiggum’s guidance to scientists:

Winning influence through (the right levels of) fear

I am supportive of vaccine mandates, especially for preventable childhood diseases like measles, but that’s not even what I’m talking about here, exactly. Americans are aggressively individualistic, and it’s probably true that telling people that they have to get vaccinated makes people less likely to want to get vaccinated.

What I’m really pushing for: we have to change the narrative such that people want to get their children vaccinated.

I am, in general, against the politics of fear. But this is something we need to be fearful of. Not every day, but just enough to remember that our fragile truce with disease is always perilously close to crumbling—especially with the anti-vaccination movement gaining steam.

Feel free to share this post with someone who will find this interesting. If you’re reading this email because someone sent it to you, please consider subscribing.

Note: A few people have told me that these emails are sometimes going into spam folders. If you a) mark the email as “not spam” and b) add [email protected] to your contacts, that should address the issue.

Or maybe you already have!

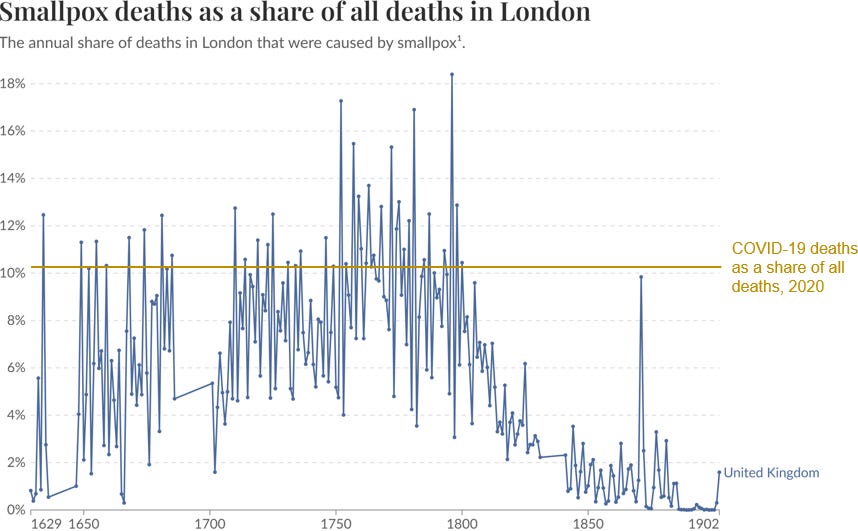

Below is one localized example of that. Data isn’t as readily available going back to the 19th century and earlier, but for literally centuries in London, smallpox was one of the leading causes of death:

|

For context (added into the graph above): COVID-19 was responsible for about 10.3% of all deaths in 2020, at the height of the pandemic.

Take a moment to reflect on that: for 50 years, people in London were dealing with COVID-level death rates from smallpox basically every single year. (What’s lost on this chart: far more of the deaths were children and young adults than was the case with COVID, and there were lots of other diseases going around too.) With the miracle of vaccines, no one in the world has died of smallpox in nearly 50 years.

h/t to Randall Munroe and xkcd for that framing.

I try not to resort to ad hominem attacks. But a) as I said above, this is one of the issues about which I am most passionate and most upset, and b) Bobby Kennedy, Jr. is responsible for needless deaths and needless suffering. He grew up with every privilege and educational opportunity in the world and should know better.

Because of this, I have no problem saying that of the 340 million of us, he’s one of the worst. I’m defining this in the utilitarian sense, where he’s singularly responsible for more harm than almost anyone else. He might not be the most evil, though he’s clearly got some of that in him too.

In fairness, this phenomenon isn’t limited to the United States. Take Japan, where vaccine hesitancy is high, and which had some of the lowest and slowest COVID-19 vaccination rates. It isn’t just in the U.S. where we’re victims of our own successes.

Notably: this is not cleanly a left-right issue. People on both sides of the aisle are susceptible to misinformation.

Paul Alexander, a polio survivor who lived in an iron lung for seven decades, died just last year. He was one of the very last people still using an iron lung.

Unsurprisingly, Gaines County also had one of the lowest COVID-19 vaccination rates in the U.S.

Frighteningly, the MMR vaccination rate in St. Louis is shockingly low, and something in our own backyard that we have to address.

I confirmed, by the way, that Bobby Kennedy, Jr. didn’t screw around with this webpage. Looking at an old vintage of the website (for measles and for polio), as far as I can tell, he hasn’t.

To be precise, that counts people who trust the CDC “a great deal” or “a fair amount.” People who trust the CDC “not much” and “not at all” were excluded from my count.

Obviously, the CDC has an enormous role to play in conducting research, finding cures, and funding life-saving efforts. It also informs how doctors talk to their patients—and 82% of Americans say that they trust their doctors.