| Know better. Do better. |  | Climate. Change.News from the ground, in a warming world |

|

| | | By Jack Graham | Climate Journalist | | |

|  |

| "A nuclear winter"As a child, I was taken around the world from Pacific coastlines to Arctic waters - through a small TV screen, led by the distinctive voice of David Attenborough.

If you're reading this newsletter, I'd imagine you have similar memories.

Watching the now 99-year-old's new documentary called “Ocean,” a few tears escaped down my cheeks.

Not because the film is a delicate swansong for the great naturalist. Because what's shown on screen is brutal and heartbreaking.

Attenborough's team managed to get first-of-its-kind footage of bottom trawling - a fishing practice where heavy nets are dragged along the sea floor and kill most life in their wake. My colleague Beatrice Tridimas wrote a helpful explainer on it last week.

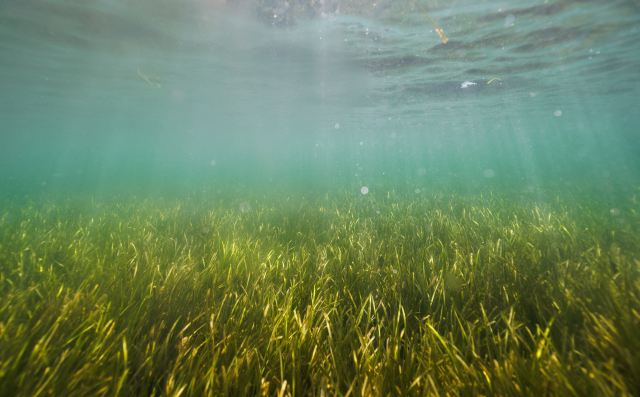

Scientists say it can destroy whole habitats like seagrasses and reefs, create huge amounts of bycatch and release planet-heating carbon in the process. Yet bottom trawling is still pervasive around the world - even in marine protected areas.  Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham |

In the film, a scallop diver on the Isle of Arran in Scotland explained what he saw when exploring a freshly trawled area:

“It was like swimming over the garden of Eden to a nuclear winter," he said.

You can even see it from space. My jaw dropped when the film showed the routes of trawling boats visible from satellite images.

Ocean campaigners often complain to me that these issues are not given the attention they deserve. And given the role that our ocean plays in the climate, they're probably right.

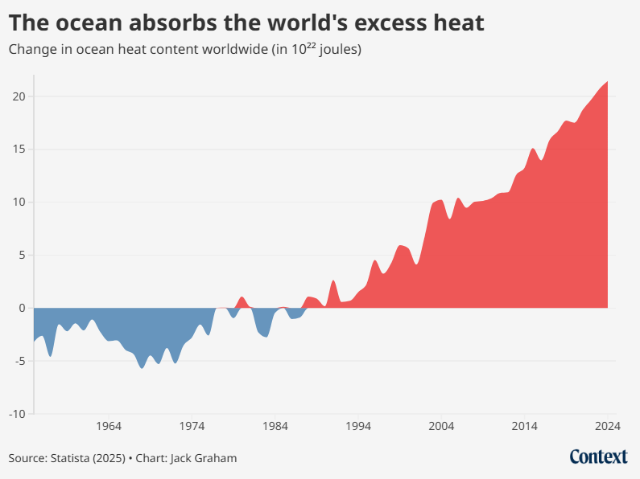

The ocean absorbs 90% of the extra heat the world is producing from planet-heating greenhouse gas emissions, produces half the oxygen we breathe and regulates global weather patterns.

The trouble is, we're not doing a very good job at protecting it.  The sun lights up a seagrass meadow close to the beach of Falckenstein, near Kiel, Germany, July 10, 2023. REUTERS/Lisi Niesner |

Paper parksLast week, governments met in Nice, France, for the third U.N. Oceans Conference to try to tackle some of these issues. Around 60 world leaders came to put oceans in the spotlight.

Countries came a step closer to ratifying an agreement to protect the high seas, several financial pledges were announced – including €1 billion from the European Commission - and the week ended with a firm political declaration to boost ocean action.

But the talks are not legally binding. It will be up to countries themselves to add teeth to their marine protected areas, often referred to as MPAs.

The world has agreed to protect 30% of the oceans by 2030, but currently only 8.6% is reported as protected - and just 2.7% effectively protected, according to an annual report by international NGOs.

"The majority of our MPAs in Europe are paper parks. They only exist on paper," said Nicolas Fournier from Oceana, a marine conservation organisation.

Oceana is part of a coalition of non-profits taking legal action over the European Union allowing bottom trawling in its protected areas.

Speaking to me before the U.N. talks, Fournier said a breakthrough would require more countries to step up efforts in their own national waters. |  | The majority of our MPAs in Europe are paper parks. They only exist on paper. | | |

| |

|

Britain recently took the lead from its famous documentarian and announced plans to rapidly increase the area where bottom trawling is prohibited.

Britain is home to one of the case studies Oceana points to as good marine governance: Lyme Bay off of the Dorset and Devon coast, a famous spot for seafood like lobster and sole.

I went there a couple years ago to see for myself what a protected area looked like. Introducing strict restrictions, including the banning of bottom trawling, wasn't easy. Fishermen were resistant, and some went out of business.

But longer term, the seabed started recovering and fish numbers increased significantly. For local fishing boats, business is good again.

"We go out, we fish, we catch for a day, and we sell it," Marc Newton, a fourth-generation fishmonger in the Devon village of Beer told me.

"We don't have any waste. That's sustainability to me."

See you next time,

Jack |

|

|

|