May 30, 2025

Permission to republish original opeds and cartoons granted.

1977 House Report: IEEPA ‘Basically Parallels Section 5(b) Of The Trading With The Enemy Act’ That Allows President To ‘Regulate… Importation’ Of Goods

|

|

|

The 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) “defines the international emergency economic authorities available to the President in the circumstances specified in section 202. This grant of authorities basically parallels 15 section 5(b) of the Trading With the Enemy Act.” That was a 1977 House Report on the adoption of the IEEPA that was used by President Donald Trump on April 2 in declaring a national trade emergency following the record $1.2 trillion trade in goods deficit in 2024 and levying reciprocal tariffs on U.S. trade partners, delineating that, with certain limitations, the powers granted in 1977 under the IEEPA “basically parallel” those that had existed under the 1917 Trading With the Enemy Act. In other words, the things that the President could do under the Trading With the Enemy Act were still things he could do under the IEEPA. That includes under 50 U.S. Code Sec. 1702 the power to “regulate… importation” of goods. The original intent of the legislation is important because in 1971, under the Trading With the Enemy Act, then-President Richard Nixon had declared a national emergency pursuant to the U.S. trade in goods deficit, then just $2.2 billion, and levied 10 percent duties on every trade partner in the world across the board. And in 1975, the U.S. Court for International Trade upheld Nixon’s decision, finding in Yoshida v. United States that “Congress, in enacting § 5(b) of the TWEA, authorized the President, during an emergency, to exercise the delegated substantive power, i.e., to ‘regulate importation,’ by imposing an import duty surcharge…” So it is with the Trading With the Enemy Act, so it is with the IEEPA. Or is it? On May 28, the U.S. Court for International Trade modified its prior standard and precedent as it relates to emergency tariffs in a case against President Trump’s reciprocal and other tariffs found that while Nixon’s actions were “limited” that those by Trump were not. The court conspicuously ignored this part of the House report. Who should we believe? The House report of the bill’s authors, or the court that ignores their clear statement of legislative intent on purpose? |

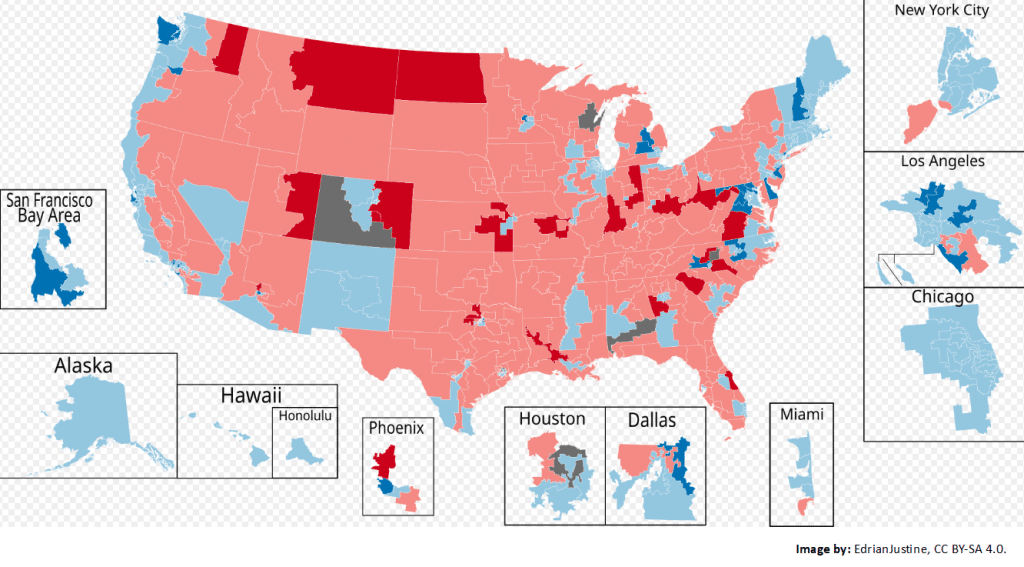

All Eyes On 16 House Crossover Districts in 2026 — But Dems Are Overextended into Potential Conservative Territory

|

|

|

In a recent Washington Post op-ed, Harrison Lavelle and Leon Sit pointed out the fact that while Democrats are sitting at an advantage heading into the midterm elections in terms of their party’s propensity for turning out in off-year elections, Democrats are over-leveraged into areas that may not be as friendly as they hope. At the center of this debate are 16 “crossover” U.S. House districts scattered across the country — districts where voters split their ticket between one party for Congress and the opposing party for president in 2024. According to analysis from the University of Virginia Center for Politics, Democrats are significantly more over-leveraged into potential conservative-friendly territory than Republicans are, with 13 of the 16 crossover House districts having elected a Democrat for Congress but voted for President Donald Trump for president. The other three districts voted for a Republican for Congress but favored Kamala Harris for president. These crossover districts will play a key role in 2026 because they represent districts where voter partisan allegiances are far from guaranteed, and where voter sentiment is relatively fluid. Democrats are now defending 13 seats in districts across the country where the district voted for President Trump’s populist approach to issues like taxes, border security, and trade. These issues are continuing to play a central role in political divisions in 2026. Democratic losses among swing-voter groups, particularly Latino voters, are escalating, and many of these districts include a significant share of Latino voters who are at risk of sitting out the election — or flipping their support to the Republican side. |

1977 House Report: IEEPA ‘Basically Parallels Section 5(b) Of The Trading With The Enemy Act’ That Allows President To ‘Regulate… Importation’ Of Goods

By Robert Romano

The 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) “defines the international emergency economic authorities available to the President in the circumstances specified in section 202. This grant of authorities basically parallels 15 section 5(b) of the Trading With the Enemy Act.”

That was a 1977 House Report on the adoption of the IEEPA that was used by President Donald Trump on April 2 in declaring a national trade emergency following the record $1.2 trillion trade in goods deficit in 2024 and levying reciprocal tariffs on U.S. trade partners, delineating that, with certain limitations, the powers granted in 1977 under the IEEPA “basically parallel” those that had existed under the 1917 Trading With the Enemy Act.

In other words, the things that the President could do under the Trading With the Enemy Act were still things he could do under the IEEPA. That includes under 50 U.S. Code Sec. 1702 the power to “regulate… importation” of goods.

The original intent of the legislation is important because in 1971, under the Trading With the Enemy Act, then-President Richard Nixon had declared a national emergency pursuant to the U.S. trade in goods deficit, then just $2.2 billion, and levied 10 percent duties on every trade partner in the world across the board.

And in 1975, the U.S. Court for International Trade upheld Nixon’s decision, finding in Yoshida v. United States that “Congress, in enacting § 5(b) of the TWEA, authorized the President, during an emergency, to exercise the delegated substantive power, i.e., to ‘regulate importation,’ by imposing an import duty surcharge…”

So it is with the Trading With the Enemy Act, so it is with the IEEPA. Or is it?

On May 28, the U.S. Court for International Trade modified its prior standard and precedent as it relates to emergency tariffs in a case against President Trump’s reciprocal and other tariffs found that while Nixon’s actions were “limited” that those by Trump were not.

It also found, remarkably, that “The legislative history surrounding IEEPA confirms that the words ‘regulate... importation’ have a narrower meaning than the power to impose any tariffs whatsoever… Congress enacted IEEPA to limit executive authority over international economic transactions, not merely to continue the executive authority granted by TWEA.”

That, even though the House report — which the court later selectively quoted — explicitly stated “This grant of authorities basically parallels 15 section 5(b) of the Trading With the Enemy Act.”

The court conspicuously ignored this part of the House report. Who should we believe? The House report of the bill’s authors, or the court that ignores their clear statement of legislative intent on purpose? The 2025 court even agreed that “both TWEA and IEEPA authorize the President to ‘regulate . . . importation.’” But that somehow, it is more “limited” under IEEPA. How? Why didn’t House report mention that?

The court’s decision has now been stayed by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on May 29. And it’s just as well.

Yes, Congress did limit the executive authority from the Trading With the Enemy Act, and the House report said how: “the authorities granted to the President by this title may be used to deal with such a threat, if the President declares a national emergency with respect to the threat, that they may only be used to deal, with that threat and not for any other purpose, and that the exercise of the authorities to deal with any new threat would require a new declaration of national emergency. By its own terms, and with repeal by section 101 (c) of this bill of the temporary exemption for section 5(b), the provisions of the National Emergencies Act are applicable to any exercise of authorities pursuant to any declaration of national emergency.”

And that, “Whenever a President declares a national emergency under section 202 of the bill, all of the above provisions automatically apply to the exercise of the authorities of section 203 of the bill under that declaration of national emergency.” Those provisions included: “the provisions of the National Emergencies Act are applicable to any exercise of authorities pursuant to any declaration of national emergency. Pertinent provisions of the National Emergencies Act provide that: (1) the President may declare a national emergency with respect to acts of Congress authorizing special or extraordinary power during time of national emergency, and that such declaration must be immediately transmitted to Congress and published in the Federal Register; (2) emergency authorities conferred by such acts of Congress are effective only when the President specifically declares a national emergency, and only if exercised in accordance with the National Emergencies Act; (3) national emergencies may be terminated by Presidential proclamation or by concurrent resolution of the Congress; (4) every 6 months that a national emergency remains in effect, each House must vote on a concurrent resolution on whether to terminate the emergency; (5) any national emergency declared by the President and not otherwise previously terminated will terminate on its anniversary date if, within 90 days prior to each anniversary date, the President does not publish in the Federal Register and transmit to Congress a notice that the emergency will continue in effect; (6) the President may not exercise any emergency power conferred by statute without specifying the statutory basis for his action; (.7) the President must keep and promptly transmit to Congress adequate records of all Executive orders and proclamations, rules and regulations, issued pursuant to a declaration of war or national emergency; and (8) during time of war or national emergency the President must transmit to Congress every 6 months a report on expenditures directly attributable to the exercise, of emergency authorities.” Trump properly declared the emergency in his executive order with all due notice.

There were further limitations outlined: “This grant of authorities does not include the following authorities which, under section 5(b) of the Trading With the Enemy Act, as amended by title I of this bill, are available to the President in time of declared war: (1) the power to vest, i.e., to take title to foreign property; (2) the power to regulate purely domestic transaction; 2 3 (3) the power to regulate gold or bullion; and (4) the power to seize records. Section 203(b) of the bill states that the authority granted to the President by this section does not include the authority to regulate or prohibit, and should not be used with the effect of regulating or prohibiting, personal communications which do not involve the transfer of aii3'thihg of value, or uncompensated transfers of anything of value except if the President determines that such transfers would seriously impair his ability to deal with the emergency, are in response to coercion against the recipient or donor, or would endanger U.S. Armed Forces.” Trump did not do any of those things with his reciprocal tariff order.

Further, the House report explicitly stated that it had only narrowed the scope of the grant from the Trading With the Enemy Act to only include those items with a “national security, foreign policy or econom[ic]” purpose: “It is the intent of the committee by this provision to reserve title II of the bill as an authority-for the regulation of international commercial and financial transactions as necessary to protect the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.”

In other words, the limitation that Congress enacted in 1977 was to put the exercise of the emergency economic powers — which admittedly include the power to “regulate… importation” — to the terms of the 1976 National Emergencies Act. That was the limited intent of the IEEPA as Congress was highly attentive to the fact that it did not wish to hinder a future president’s ability to deal with a bona fide emergency in the “national security, foreign policy or econom[ic]” sphere. That’s it.

Congress’ concern was that the powers could be used to restrict communications and other items that might violate the First Amendment, provisions that have absolutely nothing to do with President Trump’s order.

The only real difference the court could find was that in 1971 Nixon set one tariff rate, while in 2025, Trump set them on a country-by-country basis: “President Trump’s tariffs do not include the limitations that the court in Yoshida II relied upon in upholding President Nixon’s actions under TWEA. Where President Nixon’s tariffs were expressly limited by the rates established in the HTSUS, see Proclamation No. 4074, 85 Stat. at 927, the tariffs here contain no such limit.”

The implication is that if Trump revised his tariffs to a flat rate like Nixon, it would be okay — even if the rate might overshoot in some countries and undershoot in others to deal with the emergency, thereby undermining the ability of the tariffs to truly address the trade deficits or provoke meaningful discussions with trade partners on an individualized basis.

In other words, Trump’s intent with the emergency he declared was to initiate bilateral trade discussions with U.S. trading partners on a reciprocal basis, discussions that were initiated almost immediately. That way, Trump could use the tariff level as a mechanism to encourage other nations to reduce their own tariff and non-tariff barriers.

If the courts force a rule whereby emergency tariffs can only be set at a single flat rate, it would render them useless as the negotiating tool, undermining the President’s ability to conduct foreign affairs. But, then again, maybe that’s the entire point of the ruling after all.

Robert Romano is the Executive Director of Americans for Limited Government Foundation.

To view online: https://dailytorch.com/2025/05/1977-house-report-ieepa-basically-parallels-section-5b-of-the-trading-with-the-enemy-act-that-allows-president-to-regulate-importation-of-goods/

All Eyes On 16 House Crossover Districts in 2026 — But Dems Are Overextended into Potential Conservative Territory

By Manzanita Miller

In a recent Washington Post op-ed, Harrison Lavelle and Leon Sit pointed out the fact that while Democrats are sitting at an advantage heading into the midterm elections in terms of their party’s propensity for turning out in off-year elections, Democrats are over-leveraged into areas that may not be as friendly as they hope.

At the center of this debate are 16 “crossover” U.S. House districts scattered across the country — districts where voters split their ticket between one party for Congress and the opposing party for president in 2024.

According to analysis from the University of Virginia Center for Politics, Democrats are significantly more over-leveraged into potential conservative-friendly territory than Republicans are, with 13 of the 16 crossover House districts having elected a Democrat for Congress but voted for President Donald Trump for president. The other three districts voted for a Republican for Congress but favored Kamala Harris for president.

These crossover districts will play a key role in 2026 because they represent districts where voter partisan allegiances are far from guaranteed, and where voter sentiment is relatively fluid.

Democrats are now defending 13 seats in districts across the country where the district voted for President Trump’s populist approach to issues like taxes, border security, and trade. These issues are continuing to play a central role in political divisions in 2026. Democratic losses among swing-voter groups, particularly Latino voters, are escalating, and many of these districts include a significant share of Latino voters who are at risk of sitting out the election — or flipping their support to the Republican side.

One of the crossover districts is Texas’ 34th Congressional District, a majority-Latino district that encompasses parts of the southern Gulf Coast. The district reelected Democrat Vicente Gonzalez for U.S. House in 2024, defeating Republican challenger Mayra Flores with 51.3 percent of the vote to her 48.7 percent. Despite narrowly rejecting Flores as a Republican newcomer, the heavily Latino district voted for President Trump by 4.4 points, 51.8 percent to 47.4 percent. Texas’ 34th District is heavily Latino, with 91 percent of the district identified as Latino according to the U.S. Census. This district represents an opportunity for Republicans to capture the House seat in 2026, but Democrats are also eyeing the district with hopes of retaining power.

Texas’ heavily-Latino 28th Congressional District, which covers a region from the eastern edge of San Antonio to the U.S.-Mexico border is also on the watch list. The district is 75 percent Latino, and voted for President Trump by 7.3 points, 53.1 percent to 45.8 percent. However, the district reelected Democrat incumbent Henry Cuellar alongside President Trump. Texas’ 28th District represents an opportunity for conservatives to appeal to the Latino vote again in 2026, as voters are already open to the president’s America First approach.

Another target is California’s 13th Congressional District, which clocks in at 66 percent Latino, and voted for Trump by 5.4 points, 51.3 percent to 45.9 percent. The district narrowly elected a Democrat to Congress, with Adam Gray securing the district by less than 200 votes against Republican incumbent John Duarte. The razor-thin margin indicates the district could be in play for conservatives next year with the right approach.

The full list of crossover districts is available from the University of Virginia Center for Politics, and these districts will be in the spotlight heading into the midterm elections. Conservatives’ approach will vary by district, but several of the districts in California, Texas, New Mexico and Nevada include dense Latino populations that embraced President Trump’s America First set of priorities but chose to elect a Democrat to the House of Representatives. This could change in 2026, and watching these districts will be important to gauge how the Latino vote is engaging with both parties in a midterm election cycle.

Manzanita Miller is the senior political analyst at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.

To view online: https://dailytorch.com/2025/05/all-eyes-on-16-house-crossover-districts-in-2026-but-dems-are-overextended-into-potential-conservative-territory/