Email

New 50-State Data; Why waiving prison medical copays isn't all its cracked up to be.

| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | New 50-State Data; Why waiving prison medical copays isn't all its cracked up to be. |

| Date | May 15, 2025 2:38 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Waivers for prison medical copays sound nice. But they can't fix a broken system.

Prison Policy Initiative updates for May 15, 2025 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Policies for waiving medical copays in prisons are not enough to undo the harm caused by charging incarcerated people for health care access [[link removed]] Our review of copay policies show that exemptions are so limited, ill-defined, and inconsistent that they fail to make the copay system less harmful for incarcerated people. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra and Dr. Emily Lupez

In most states, people incarcerated in prisons must pay medical “copays, [[link removed]]” which are essentially fees to access health care including physician visits, medications, dental treatment, and other health services. While these fees may seem reasonable at two or five dollars, research shows they actually act as barriers to health care for incarcerated people who typically [[link removed]] earn less than a dollar an hour, if they are paid at all. Prison administrators claim these fees deter the “ overuse and abuse [[link removed]]” of limited health care resources, and have countered critiques by including waivers and exceptions in their copay policies and insisting that no one is denied care because they can’t afford to pay. However, our review of these policies and evidence from a recent study show that these exemptions are so limited, ill-defined, and inconsistent that they fail to make the copay system fairer and less harmful for incarcerated people. Instead, these exemptions lend a veneer of rationality to prison medical fee policies — which are known to limit access to care — ultimately helping to perpetuate them.

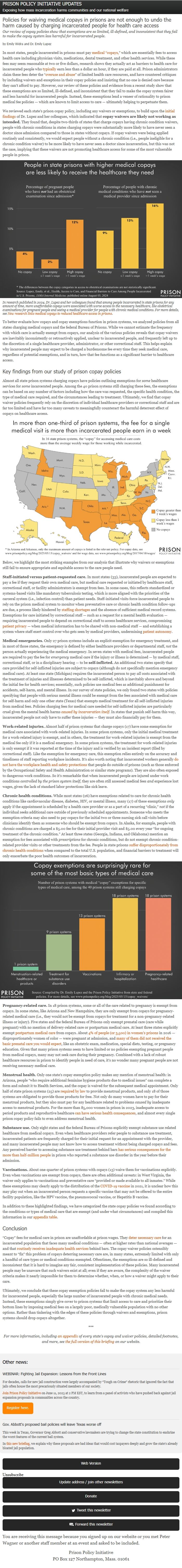

We reviewed each state’s prison copay policy, including any waivers or exemptions, to build upon the initial findings [[link removed]] of Dr. Lupez and her colleagues, which indicated that copay waivers are likely not working as intended. They found that, despite two-thirds of states that charge copays having chronic condition waivers, people with chronic conditions in states charging copays were substantially more likely to have never seen a doctor since admission compared to those in states without copays. If copay waivers were being applied routinely and consistently, we would expect people without a chronic condition (i.e., people ineligible for a chronic condition waiver) to be more likely to have never seen a doctor since incarceration, but this was not the case, implying that these waivers are not promoting healthcare access for some of the most vulnerable people in prison.

In research published in 2024, Dr. Lupez and her colleagues found that among people incarcerated in state prisons for any amount of time, more unaffordable copays were associated with worse access to the necessary healthcare, like obstetrical examinations for pregnant people and seeing a medical provider for people with chronic medical conditions. For more details, see New research links medical copays to reduced healthcare access in prisons [[link removed]].

To better evaluate how copays and copay exemptions function in prison systems, we analyzed policies from all states charging medical copays and the federal Bureau of Prisons. While we cannot estimate the frequency with which care is actually exempt from copays, our analysis of the various policies reveals that copay waivers are inevitably inconsistently or retroactively applied, unclear to incarcerated people, and frequently left up to the discretion of a single healthcare provider, administrator, or other correctional staff. This helps explain why incarcerated people may expect to be charged a burdensome fee every time they seek medical care, regardless of potential exemptions, and in turn, how that fee functions as a significant barrier to healthcare access.

Key findings from our study of prison copay policies

Almost all state prison systems charging copays have policies outlining exemptions for some healthcare services for some incarcerated people. Among the 40 prison systems still charging these fees, the exemptions can be based on any number of factors including how the care was requested, the specific health condition, the type of medical care required, and the circumstances leading to treatment. Ultimately, we find that copay waiver policies frequently rely on the discretion of individual healthcare providers or correctional staff and are far too limited and have far too many caveats to meaningfully counteract the harmful deterrent effect of copays on healthcare access.

Below, we highlight the most striking examples from our analysis that illustrate why waivers or exemptions still fail to ensure appropriate and equitable access to the care people need.

Staff-initiated versus patient-requested care. In most states (33), incarcerated people are expected to pay a fee if they request their own medical care, but medical care requested or initiated by healthcare staff, correctional staff, or facility administrators is exempt from fees. In some cases, this reflects standardized or systems-based visits like mandatory tuberculosis testing, which is more aligned with the priorities of the carceral system (i.e., infection control) than patient needs. Staff-initiated visits force incarcerated people to rely on the prison medical system to monitor when preventative care or chronic health condition follow-ups are due, a process likely hindered by staffing shortages [[link removed]] and the absence of sufficient medical record systems. Exemptions for care initiated by correctional staff — such as a request for a mental health evaluation — requiring incarcerated people to depend on correctional staff to access healthcare services, compromising patient privacy [[link removed]] — when medical information has to be shared with non-medical staff — and establishing a system where staff exert control over who gets seen by medical providers, undermining patient autonomy [[link removed]].

Medical emergencies. Only 27 prison systems include an explicit exemption for emergency treatment, and in most of those states, the emergency is defined by either healthcare providers or departmental staff, not the person actually experiencing the medical emergency. In seven states with medical fees, incarcerated people are required to pay the fee for emergency medical care if the injury or illness is determined — by medical staff, correctional staff, or in a disciplinary hearing — to be self-inflicted. An additional two states specify that care provided for self-inflicted injuries are subject to copays (although do not specifically mention emergency medical care). At least one state (Michigan) requires the incarcerated person to pay all costs associated with the treatment of injuries and illnesses determined to be self-inflicted, which is inevitably above and beyond the initial fee for health services; essentially, such policies use medical fees as additional punishment for accidents, self-harm, and mental illness. In our survey of state policies, we only found two states with policies specifying that people with serious mental illness could be exempt from the fees associated with medical care for self-harm and only one other state (Texas) that exempts medical treatment for all self-inflicted injuries from medical fees. Policies charging fees for medical care needed for self-inflicted injuries are particularly cruel given the mental health harms caused by incarceration itself [[link removed]]. In states that punish self-harm this way, incarcerated people not only have to suffer these injuries — they must also financially pay for them.

Work-related injuries. Almost half of prison systems that charge copays (17) have some exemption for medical care associated with work-related injuries. In some prison systems, only the initial medical treatment for a work-related injury is exempt, and in others, the treatment for work-related injuries is exempt from the medical fee only if it is a medical emergency. In some prison systems, the treatment for work-related injuries is only exempt if it was reported at the time of the injury and is verified by an incident report (filed by correctional staff). Like the exemption for emergency care, this exemption relies entirely on the accuracy and timeliness of staff reporting workplace incidents. It’s also worth noting that incarcerated workers generally do not have the workplace health and safety protections [[link removed]] that people do outside of prisons (such as those enforced by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration or similar state programs). They are also often exposed to dangerous work conditions. So it’s remarkable that when incarcerated people are injured under work conditions controlled by the prison system itself, they are often still assessed medical fees and experience lost wages, given the lack of standard labor protections like sick leave.

Chronic health conditions. While most states (26) have exemptions related to care for chronic health conditions like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, HIV, or mental illness, many (17) of these exemptions only apply if the appointment is scheduled by a health care provider or as a part of a recurring “clinic,” not if the individual seeks additional care outside of previously scheduled appointments. Someone who meets the exemption criteria may also need to pay copays for the initial two or three nursing sick call visits before clinicians identify them as someone who should be exempt from copays. In Alaska, for example, people with chronic conditions are charged a $5.00 fee for their initial provider visit and $5.00 every year “for ongoing treatment of the chronic condition.” At least three states (Georgia, Indiana, and Oklahoma) mention an exemption for fees associated with prescriptions for chronic conditions, but do not exempt chronic condition-related provider visits or other treatments from the fee. People in state prisons suffer disproportionately from chronic health conditions [[link removed]] when compared to the total U.S. population, and financial barriers to treatment will only exacerbate the poor health outcomes of incarceration.

Pregnancy-related care. In 18 prison systems, some or all of the care related to pregnancy is exempt from copays. In some states, like Arizona and New Hampshire, they are only exempt from copays for pregnancy-related medical care (i.e., they would not be exempt from copays for treatment for a non-pregnancy-related illness or injury). Five states and the federal Bureau of Prisons only exempt prenatal care (care while pregnant) with no mention of delivery-related care or postpartum medical care. At least three states explicitly exempt postpartum medical care [[link removed]] from copays. About 4% of people (or 3,500) in women’s prisons [[link removed]] in 2016 — disproportionately women of color — were pregnant at admission, and many of them did not received the basic prenatal care you would expect [[link removed]], like an obstetric exam, medication, special diets, testing, or pregnancy education. Given that many prison systems seem to have limited or no policies exempting pregnant people from medical copays, many may not seek care during their pregnancy. Combined with a lack of robust healthcare resources in prison to identify people in need of care, it’s no wonder many pregnant people are not receiving necessary medical care.

Menstrual health. Only one state’s copay exemption policy makes any mention of menstrual health: in Arizona, people “who require additional feminine hygiene products due to medical issues” can complete a form and submit it to Health Services, and the copay is waived for the subsequent medical appointment. Only half of state prison systems (25) are required by law [[link removed]] to provide menstrual products, and only 18 of those systems are obligated to provide those products for free. Not only do many women have to pay for their menstrual products, but they also must pay for any healthcare related to problems caused by inadequate access to menstrual products. For the more than 85,000 women in prison in 2023, inadequate access to period products and reproductive healthcare can have serious health consequences [[link removed]], and almost every single prison copay policy fails to even address menstrual health.

Substance use. Only eight states and the federal Bureau of Prisons explicitly exempt substance use related healthcare from medical copays. Even when healthcare providers refer people to substance use treatment, incarcerated patients are frequently charged for their initial request for an appointment with the provider, and many incarcerated people may not know how to access treatment without being charged copays and fees. Any perceived barrier to accessing substance use treatment behind bars has serious consequences for the more than half-million people [[link removed]] in prison who reported a substance use disorder in the year before their admission.

Vaccinations. About one-quarter of prison systems with copays (13) waive them for vaccinations explicitly. Even when vaccinations are exempt from copays, there are often additional caveats: in West Virginia, the waiver only applies to vaccinations and preventative care “provided or made available to all inmates.” While these exemptions may clearly apply to the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine [[link removed]] in 2021, it is unclear how this may play out when an incarcerated person requests a specific vaccine that may not be offered to the entire facility population, like the HPV vaccine, the pneumococcal vaccine, or Hepatitis B vaccine.

In addition to these highlighted findings, we have categorized the state copay policies we found according to the conditions or types of medical care that are exempt (and under what circumstances) and compiled this information in our appendix table [[link removed]].

Conclusion

“Copay” fees for medical care in prison are unaffordable at prison wages. They deter necessary care [[link removed]] for an incarcerated population that faces many medical conditions — often at higher rates than national averages — and that routinely receives inadequate health services [[link removed]] behind bars. The copay waiver policies ostensibly meant to “fix” this problem of copays deterring necessary care are, in many states, extremely limited with only a handful of care types or medical conditions exempted. Oftentimes, the exemptions are so ill-defined and inconsistent that it is hard to imagine any fair, consistent implementation of these policies. Many incarcerated people may be unaware that such waivers exist at all; even if they are aware, the complexity of the waiver criteria makes it nearly impossible for them to determine whether, when, or how a waiver might apply to their care.

Ultimately, we conclude that these copay exemption policies fail to make the copay system any less harmful for incarcerated people, especially the large number of incarcerated people with chronic medical needs. Instead, these exemptions simply give cover to prison systems that limit access to care and prioritize their bottom lines by imposing medical fees on a largely poor, medically vulnerable population with no other options. Rather than tinkering with the edges of these policies through waivers and exemptions, prison systems should drop copays altogether.

***

For more information, including an appendix [[link removed]] of every state's copay and waiver policies, detailed footnotes, and more, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: WEBINAR: Fighting Jail Expansion: Lessons from the Front Lines [[link removed]]

For decades, calls for new jail construction were largely accompanied by “Tough on Crime” rhetoric that ignored the fact that jails often house the most precariously situated members of our society.

Join Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]] on June 11, 2025 at 2 PM EST, to learn from a panel of activists who have pushed back against jail expansion proposals in communities across the country.

Register here. [[link removed]]

Gov. Abbott's proposed bail policies will leave Texas worse off [[link removed]]

This week in Texas, Governor Greg Abbott and conservative lawmakers are trying to change the state constitution to enshrine the worst features of the current bail system.

In this new briefing [[link removed]], we explain why these proposals are bad ideas that would cost taxpayers deeply and grow the state's already bloated jail population.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for May 15, 2025 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Policies for waiving medical copays in prisons are not enough to undo the harm caused by charging incarcerated people for health care access [[link removed]] Our review of copay policies show that exemptions are so limited, ill-defined, and inconsistent that they fail to make the copay system less harmful for incarcerated people. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra and Dr. Emily Lupez

In most states, people incarcerated in prisons must pay medical “copays, [[link removed]]” which are essentially fees to access health care including physician visits, medications, dental treatment, and other health services. While these fees may seem reasonable at two or five dollars, research shows they actually act as barriers to health care for incarcerated people who typically [[link removed]] earn less than a dollar an hour, if they are paid at all. Prison administrators claim these fees deter the “ overuse and abuse [[link removed]]” of limited health care resources, and have countered critiques by including waivers and exceptions in their copay policies and insisting that no one is denied care because they can’t afford to pay. However, our review of these policies and evidence from a recent study show that these exemptions are so limited, ill-defined, and inconsistent that they fail to make the copay system fairer and less harmful for incarcerated people. Instead, these exemptions lend a veneer of rationality to prison medical fee policies — which are known to limit access to care — ultimately helping to perpetuate them.

We reviewed each state’s prison copay policy, including any waivers or exemptions, to build upon the initial findings [[link removed]] of Dr. Lupez and her colleagues, which indicated that copay waivers are likely not working as intended. They found that, despite two-thirds of states that charge copays having chronic condition waivers, people with chronic conditions in states charging copays were substantially more likely to have never seen a doctor since admission compared to those in states without copays. If copay waivers were being applied routinely and consistently, we would expect people without a chronic condition (i.e., people ineligible for a chronic condition waiver) to be more likely to have never seen a doctor since incarceration, but this was not the case, implying that these waivers are not promoting healthcare access for some of the most vulnerable people in prison.

In research published in 2024, Dr. Lupez and her colleagues found that among people incarcerated in state prisons for any amount of time, more unaffordable copays were associated with worse access to the necessary healthcare, like obstetrical examinations for pregnant people and seeing a medical provider for people with chronic medical conditions. For more details, see New research links medical copays to reduced healthcare access in prisons [[link removed]].

To better evaluate how copays and copay exemptions function in prison systems, we analyzed policies from all states charging medical copays and the federal Bureau of Prisons. While we cannot estimate the frequency with which care is actually exempt from copays, our analysis of the various policies reveals that copay waivers are inevitably inconsistently or retroactively applied, unclear to incarcerated people, and frequently left up to the discretion of a single healthcare provider, administrator, or other correctional staff. This helps explain why incarcerated people may expect to be charged a burdensome fee every time they seek medical care, regardless of potential exemptions, and in turn, how that fee functions as a significant barrier to healthcare access.

Key findings from our study of prison copay policies

Almost all state prison systems charging copays have policies outlining exemptions for some healthcare services for some incarcerated people. Among the 40 prison systems still charging these fees, the exemptions can be based on any number of factors including how the care was requested, the specific health condition, the type of medical care required, and the circumstances leading to treatment. Ultimately, we find that copay waiver policies frequently rely on the discretion of individual healthcare providers or correctional staff and are far too limited and have far too many caveats to meaningfully counteract the harmful deterrent effect of copays on healthcare access.

Below, we highlight the most striking examples from our analysis that illustrate why waivers or exemptions still fail to ensure appropriate and equitable access to the care people need.

Staff-initiated versus patient-requested care. In most states (33), incarcerated people are expected to pay a fee if they request their own medical care, but medical care requested or initiated by healthcare staff, correctional staff, or facility administrators is exempt from fees. In some cases, this reflects standardized or systems-based visits like mandatory tuberculosis testing, which is more aligned with the priorities of the carceral system (i.e., infection control) than patient needs. Staff-initiated visits force incarcerated people to rely on the prison medical system to monitor when preventative care or chronic health condition follow-ups are due, a process likely hindered by staffing shortages [[link removed]] and the absence of sufficient medical record systems. Exemptions for care initiated by correctional staff — such as a request for a mental health evaluation — requiring incarcerated people to depend on correctional staff to access healthcare services, compromising patient privacy [[link removed]] — when medical information has to be shared with non-medical staff — and establishing a system where staff exert control over who gets seen by medical providers, undermining patient autonomy [[link removed]].

Medical emergencies. Only 27 prison systems include an explicit exemption for emergency treatment, and in most of those states, the emergency is defined by either healthcare providers or departmental staff, not the person actually experiencing the medical emergency. In seven states with medical fees, incarcerated people are required to pay the fee for emergency medical care if the injury or illness is determined — by medical staff, correctional staff, or in a disciplinary hearing — to be self-inflicted. An additional two states specify that care provided for self-inflicted injuries are subject to copays (although do not specifically mention emergency medical care). At least one state (Michigan) requires the incarcerated person to pay all costs associated with the treatment of injuries and illnesses determined to be self-inflicted, which is inevitably above and beyond the initial fee for health services; essentially, such policies use medical fees as additional punishment for accidents, self-harm, and mental illness. In our survey of state policies, we only found two states with policies specifying that people with serious mental illness could be exempt from the fees associated with medical care for self-harm and only one other state (Texas) that exempts medical treatment for all self-inflicted injuries from medical fees. Policies charging fees for medical care needed for self-inflicted injuries are particularly cruel given the mental health harms caused by incarceration itself [[link removed]]. In states that punish self-harm this way, incarcerated people not only have to suffer these injuries — they must also financially pay for them.

Work-related injuries. Almost half of prison systems that charge copays (17) have some exemption for medical care associated with work-related injuries. In some prison systems, only the initial medical treatment for a work-related injury is exempt, and in others, the treatment for work-related injuries is exempt from the medical fee only if it is a medical emergency. In some prison systems, the treatment for work-related injuries is only exempt if it was reported at the time of the injury and is verified by an incident report (filed by correctional staff). Like the exemption for emergency care, this exemption relies entirely on the accuracy and timeliness of staff reporting workplace incidents. It’s also worth noting that incarcerated workers generally do not have the workplace health and safety protections [[link removed]] that people do outside of prisons (such as those enforced by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration or similar state programs). They are also often exposed to dangerous work conditions. So it’s remarkable that when incarcerated people are injured under work conditions controlled by the prison system itself, they are often still assessed medical fees and experience lost wages, given the lack of standard labor protections like sick leave.

Chronic health conditions. While most states (26) have exemptions related to care for chronic health conditions like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, HIV, or mental illness, many (17) of these exemptions only apply if the appointment is scheduled by a health care provider or as a part of a recurring “clinic,” not if the individual seeks additional care outside of previously scheduled appointments. Someone who meets the exemption criteria may also need to pay copays for the initial two or three nursing sick call visits before clinicians identify them as someone who should be exempt from copays. In Alaska, for example, people with chronic conditions are charged a $5.00 fee for their initial provider visit and $5.00 every year “for ongoing treatment of the chronic condition.” At least three states (Georgia, Indiana, and Oklahoma) mention an exemption for fees associated with prescriptions for chronic conditions, but do not exempt chronic condition-related provider visits or other treatments from the fee. People in state prisons suffer disproportionately from chronic health conditions [[link removed]] when compared to the total U.S. population, and financial barriers to treatment will only exacerbate the poor health outcomes of incarceration.

Pregnancy-related care. In 18 prison systems, some or all of the care related to pregnancy is exempt from copays. In some states, like Arizona and New Hampshire, they are only exempt from copays for pregnancy-related medical care (i.e., they would not be exempt from copays for treatment for a non-pregnancy-related illness or injury). Five states and the federal Bureau of Prisons only exempt prenatal care (care while pregnant) with no mention of delivery-related care or postpartum medical care. At least three states explicitly exempt postpartum medical care [[link removed]] from copays. About 4% of people (or 3,500) in women’s prisons [[link removed]] in 2016 — disproportionately women of color — were pregnant at admission, and many of them did not received the basic prenatal care you would expect [[link removed]], like an obstetric exam, medication, special diets, testing, or pregnancy education. Given that many prison systems seem to have limited or no policies exempting pregnant people from medical copays, many may not seek care during their pregnancy. Combined with a lack of robust healthcare resources in prison to identify people in need of care, it’s no wonder many pregnant people are not receiving necessary medical care.

Menstrual health. Only one state’s copay exemption policy makes any mention of menstrual health: in Arizona, people “who require additional feminine hygiene products due to medical issues” can complete a form and submit it to Health Services, and the copay is waived for the subsequent medical appointment. Only half of state prison systems (25) are required by law [[link removed]] to provide menstrual products, and only 18 of those systems are obligated to provide those products for free. Not only do many women have to pay for their menstrual products, but they also must pay for any healthcare related to problems caused by inadequate access to menstrual products. For the more than 85,000 women in prison in 2023, inadequate access to period products and reproductive healthcare can have serious health consequences [[link removed]], and almost every single prison copay policy fails to even address menstrual health.

Substance use. Only eight states and the federal Bureau of Prisons explicitly exempt substance use related healthcare from medical copays. Even when healthcare providers refer people to substance use treatment, incarcerated patients are frequently charged for their initial request for an appointment with the provider, and many incarcerated people may not know how to access treatment without being charged copays and fees. Any perceived barrier to accessing substance use treatment behind bars has serious consequences for the more than half-million people [[link removed]] in prison who reported a substance use disorder in the year before their admission.

Vaccinations. About one-quarter of prison systems with copays (13) waive them for vaccinations explicitly. Even when vaccinations are exempt from copays, there are often additional caveats: in West Virginia, the waiver only applies to vaccinations and preventative care “provided or made available to all inmates.” While these exemptions may clearly apply to the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine [[link removed]] in 2021, it is unclear how this may play out when an incarcerated person requests a specific vaccine that may not be offered to the entire facility population, like the HPV vaccine, the pneumococcal vaccine, or Hepatitis B vaccine.

In addition to these highlighted findings, we have categorized the state copay policies we found according to the conditions or types of medical care that are exempt (and under what circumstances) and compiled this information in our appendix table [[link removed]].

Conclusion

“Copay” fees for medical care in prison are unaffordable at prison wages. They deter necessary care [[link removed]] for an incarcerated population that faces many medical conditions — often at higher rates than national averages — and that routinely receives inadequate health services [[link removed]] behind bars. The copay waiver policies ostensibly meant to “fix” this problem of copays deterring necessary care are, in many states, extremely limited with only a handful of care types or medical conditions exempted. Oftentimes, the exemptions are so ill-defined and inconsistent that it is hard to imagine any fair, consistent implementation of these policies. Many incarcerated people may be unaware that such waivers exist at all; even if they are aware, the complexity of the waiver criteria makes it nearly impossible for them to determine whether, when, or how a waiver might apply to their care.

Ultimately, we conclude that these copay exemption policies fail to make the copay system any less harmful for incarcerated people, especially the large number of incarcerated people with chronic medical needs. Instead, these exemptions simply give cover to prison systems that limit access to care and prioritize their bottom lines by imposing medical fees on a largely poor, medically vulnerable population with no other options. Rather than tinkering with the edges of these policies through waivers and exemptions, prison systems should drop copays altogether.

***

For more information, including an appendix [[link removed]] of every state's copay and waiver policies, detailed footnotes, and more, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: WEBINAR: Fighting Jail Expansion: Lessons from the Front Lines [[link removed]]

For decades, calls for new jail construction were largely accompanied by “Tough on Crime” rhetoric that ignored the fact that jails often house the most precariously situated members of our society.

Join Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]] on June 11, 2025 at 2 PM EST, to learn from a panel of activists who have pushed back against jail expansion proposals in communities across the country.

Register here. [[link removed]]

Gov. Abbott's proposed bail policies will leave Texas worse off [[link removed]]

This week in Texas, Governor Greg Abbott and conservative lawmakers are trying to change the state constitution to enshrine the worst features of the current bail system.

In this new briefing [[link removed]], we explain why these proposals are bad ideas that would cost taxpayers deeply and grow the state's already bloated jail population.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor