Email

The Russian Paradox: So Much Education, So Little Human Capital

| From | AEI American Enterprise <[email protected]> |

| Subject | The Russian Paradox: So Much Education, So Little Human Capital |

| Date | April 9, 2025 9:02 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

April 2025

Welcome to the April edition of The American Enterprise! This month, we are featuring pieces from Nicholas Eberstadt <[link removed]> on the paradox of Russian

educational attainment and human capital; Todd Harrison <[link removed]> on Donald Trump's push for a Golden Dome missile defense system; Frederick M. Hess <[link removed]> on the root causes of the ongoing backlash against diversity, equity, and inclusion; and Philip Wallach <[link removed]> on how Congress can keep pace with the Trump administration.

Make sure to subscribe <[link removed]> and read the online version here <[link removed]>!

The Russian Paradox: So Much Education, So Little Human Capital <[link removed]>

By Nicholas Eberstadt

Ever since Nobel laureate T. W. Schultz’s foundational 1960 lecture <[link removed]> on “human capital,” economists have documented the importance of “investing in human beings” and the crucial role that education plays in economic development.

Higher levels of educational attainment are associated with better health and lower mortality for both adults <[link removed]> and children <[link removed]> globally, even in countries where

income levels remain relatively low. Further, education’s productivity-enhancing properties abet the rise of “service economies” and “knowledge economies.” Education, and the human capital it creates, lies at the heart of modern economic development.

Yet in Russia today, we see an exception to the seemingly global correspondence between educational attainment and human capital. Russia presents the curious counterexample of a country where high levels of education coexist with strikingly poor health profiles—where the population’s considerable schooling contributes only feebly to its “knowledge production” and skills-intensive international service sector.

This Russian paradox merits attention—and not for academic reasons alone. Understanding the economic and defense potential of this large and highly schooled population will be an increasingly pressing security question as the world heads into a second cold war.

International demographic and economic data illustrate the Russian paradox. I focus on Russian conditions on the eve of the coronavirus pandemic (i.e., circa 2019) rather than trends for the early 2020s, since the demographic and economic reverberations of the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine severely complicate any effort to compare Russian readings with more recent soundings from other countries.

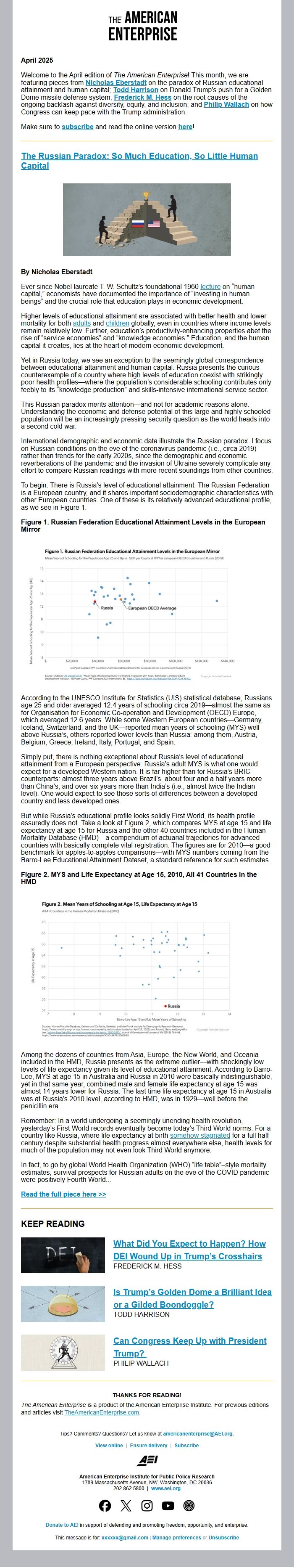

To begin: There is Russia’s level of educational attainment. The Russian Federation is a European country, and it shares important sociodemographic characteristics with other European countries. One of these is its relatively advanced educational profile, as we see in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Russian Federation Educational Attainment Levels in the European Mirror

<[link removed]>

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) statistical database, Russians age 25 and older averaged 12.4 years of schooling circa 2019—almost the same as for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Europe, which averaged 12.6 years. While some Western European countries—Germany, Iceland, Switzerland, and the UK—reported mean years of schooling (MYS) well above Russia’s, others reported lower levels than Russia: among them, Austria, Belgium, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain.

Simply put, there is nothing exceptional about Russia’s level of educational attainment from a European

perspective. Russia’s adult MYS is what one would expect for a developed Western nation. It is far higher than for Russia’s BRIC counterparts: almost three years above Brazil’s, about four and a half years more than China’s; and over six years more than India’s (i.e., almost twice the Indian level). One would expect to see those sorts of differences between a developed country and less developed ones.

But while Russia’s educational profile looks solidly First World, its health profile assuredly does not. Take a look at Figure 2, which compares MYS at age 15 and life expectancy at age 15 for Russia and the other 40 countries included in the Human Mortality Database (HMD)—a compendium of actuarial trajectories for advanced countries with basically complete vital registration. The figures are for 2010—a good benchmark for apples-to-apples comparisons—with MYS numbers coming from the Barro-Lee Educational Attainment Dataset, a standard reference for such estimates.

Figure 2. MYS and Life Expectancy at Age 15, 2010, All 41 Countries in the HMD

<[link removed]>

Among

the dozens of countries from Asia, Europe, the New World, and Oceania included in the HMD, Russia presents as the extreme outlier—with shockingly low levels of life expectancy given its level of educational attainment. According to Barro-Lee, MYS at age 15 in Australia and Russia in 2010 were basically indistinguishable, yet in that same year, combined male and female life expectancy at age 15 was almost 14 years lower for Russia. The last time life expectancy at age 15 in Australia was at Russia’s 2010 level, according to HMD, was in 1929—well before the penicillin era.

Remember: In a world undergoing a seemingly unending health revolution, yesterday’s First World records eventually become today’s Third World norms. For a country like Russia, where life expectancy at birth somehow stagnated <[link removed]> for a full half century despite substantial health progress almost everywhere else, health levels for much of the population may not even look Third World anymore.

In fact, to go by global World Health Organization (WHO) “life table”–style mortality estimates, survival prospects for Russian adults on the eve of the COVID pandemic were positively Fourth World...

Read the full piece here >> <[link removed]>

KEEP READING

What Did You Expect to Happen? How DEI Wound Up in Trump’s Crosshairs <[link removed]>

FREDERICK M. HESS

Is Trump’s Golden Dome a Brilliant Idea or a Gilded Boondoggle? <[link removed]>

TODD HARRISON

Can Congress Keep Up with President Trump? <[link removed]>

PHILIP WALLACH

THANKS FOR READING!

The American Enterprise is a product of the American Enterprise Institute. For previous editions and articles visit TheAmericanEnterprise.com <[link removed]>.

Tips? Comments? Questions? Let us know at <span style="color: #008ccc;"><strong><a href= "[link removed]" target="_blank" style="color: #008ccc;" >[email protected]</a></strong></span>.

View online | Ensure delivery <[link removed]> | Subscribe <[link removed]>

American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research

1789 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20036 <[[#]]>

202.862.5800 <[[#]]> | www.aei.org <[link removed]>

<[link removed]> <[link removed]> <[link removed]> <[link removed]>

Donate to AEI <[link removed]> in support of defending and promoting freedom, opportunity, and enterprise.

This message is for: [email protected] <[email protected]> | Manage Preferences <[link removed]> |

<!-- This is a comment -->

Welcome to the April edition of The American Enterprise! This month, we are featuring pieces from Nicholas Eberstadt <[link removed]> on the paradox of Russian

educational attainment and human capital; Todd Harrison <[link removed]> on Donald Trump's push for a Golden Dome missile defense system; Frederick M. Hess <[link removed]> on the root causes of the ongoing backlash against diversity, equity, and inclusion; and Philip Wallach <[link removed]> on how Congress can keep pace with the Trump administration.

Make sure to subscribe <[link removed]> and read the online version here <[link removed]>!

The Russian Paradox: So Much Education, So Little Human Capital <[link removed]>

By Nicholas Eberstadt

Ever since Nobel laureate T. W. Schultz’s foundational 1960 lecture <[link removed]> on “human capital,” economists have documented the importance of “investing in human beings” and the crucial role that education plays in economic development.

Higher levels of educational attainment are associated with better health and lower mortality for both adults <[link removed]> and children <[link removed]> globally, even in countries where

income levels remain relatively low. Further, education’s productivity-enhancing properties abet the rise of “service economies” and “knowledge economies.” Education, and the human capital it creates, lies at the heart of modern economic development.

Yet in Russia today, we see an exception to the seemingly global correspondence between educational attainment and human capital. Russia presents the curious counterexample of a country where high levels of education coexist with strikingly poor health profiles—where the population’s considerable schooling contributes only feebly to its “knowledge production” and skills-intensive international service sector.

This Russian paradox merits attention—and not for academic reasons alone. Understanding the economic and defense potential of this large and highly schooled population will be an increasingly pressing security question as the world heads into a second cold war.

International demographic and economic data illustrate the Russian paradox. I focus on Russian conditions on the eve of the coronavirus pandemic (i.e., circa 2019) rather than trends for the early 2020s, since the demographic and economic reverberations of the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine severely complicate any effort to compare Russian readings with more recent soundings from other countries.

To begin: There is Russia’s level of educational attainment. The Russian Federation is a European country, and it shares important sociodemographic characteristics with other European countries. One of these is its relatively advanced educational profile, as we see in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Russian Federation Educational Attainment Levels in the European Mirror

<[link removed]>

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) statistical database, Russians age 25 and older averaged 12.4 years of schooling circa 2019—almost the same as for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Europe, which averaged 12.6 years. While some Western European countries—Germany, Iceland, Switzerland, and the UK—reported mean years of schooling (MYS) well above Russia’s, others reported lower levels than Russia: among them, Austria, Belgium, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain.

Simply put, there is nothing exceptional about Russia’s level of educational attainment from a European

perspective. Russia’s adult MYS is what one would expect for a developed Western nation. It is far higher than for Russia’s BRIC counterparts: almost three years above Brazil’s, about four and a half years more than China’s; and over six years more than India’s (i.e., almost twice the Indian level). One would expect to see those sorts of differences between a developed country and less developed ones.

But while Russia’s educational profile looks solidly First World, its health profile assuredly does not. Take a look at Figure 2, which compares MYS at age 15 and life expectancy at age 15 for Russia and the other 40 countries included in the Human Mortality Database (HMD)—a compendium of actuarial trajectories for advanced countries with basically complete vital registration. The figures are for 2010—a good benchmark for apples-to-apples comparisons—with MYS numbers coming from the Barro-Lee Educational Attainment Dataset, a standard reference for such estimates.

Figure 2. MYS and Life Expectancy at Age 15, 2010, All 41 Countries in the HMD

<[link removed]>

Among

the dozens of countries from Asia, Europe, the New World, and Oceania included in the HMD, Russia presents as the extreme outlier—with shockingly low levels of life expectancy given its level of educational attainment. According to Barro-Lee, MYS at age 15 in Australia and Russia in 2010 were basically indistinguishable, yet in that same year, combined male and female life expectancy at age 15 was almost 14 years lower for Russia. The last time life expectancy at age 15 in Australia was at Russia’s 2010 level, according to HMD, was in 1929—well before the penicillin era.

Remember: In a world undergoing a seemingly unending health revolution, yesterday’s First World records eventually become today’s Third World norms. For a country like Russia, where life expectancy at birth somehow stagnated <[link removed]> for a full half century despite substantial health progress almost everywhere else, health levels for much of the population may not even look Third World anymore.

In fact, to go by global World Health Organization (WHO) “life table”–style mortality estimates, survival prospects for Russian adults on the eve of the COVID pandemic were positively Fourth World...

Read the full piece here >> <[link removed]>

KEEP READING

What Did You Expect to Happen? How DEI Wound Up in Trump’s Crosshairs <[link removed]>

FREDERICK M. HESS

Is Trump’s Golden Dome a Brilliant Idea or a Gilded Boondoggle? <[link removed]>

TODD HARRISON

Can Congress Keep Up with President Trump? <[link removed]>

PHILIP WALLACH

THANKS FOR READING!

The American Enterprise is a product of the American Enterprise Institute. For previous editions and articles visit TheAmericanEnterprise.com <[link removed]>.

Tips? Comments? Questions? Let us know at <span style="color: #008ccc;"><strong><a href= "[link removed]" target="_blank" style="color: #008ccc;" >[email protected]</a></strong></span>.

View online | Ensure delivery <[link removed]> | Subscribe <[link removed]>

American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research

1789 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20036 <[[#]]>

202.862.5800 <[[#]]> | www.aei.org <[link removed]>

<[link removed]> <[link removed]> <[link removed]> <[link removed]>

Donate to AEI <[link removed]> in support of defending and promoting freedom, opportunity, and enterprise.

This message is for: [email protected] <[email protected]> | Manage Preferences <[link removed]> |

<!-- This is a comment -->

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Marketo