| From | Peter Wagner <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Our new infographic shows the dysfunction of "compassionate release" |

| Date | May 29, 2020 5:32 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Only a tiny fraction of people who apply for compassionate release are approved

Prison Policy Initiative updates for May 29, 2020 Showing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Compassionate release was never designed to release large numbers of people [[link removed]] With help from artist Kevin Pyle, we explain why very few people who apply for compassionate release are approved — even during a pandemic. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra and Wanda Bertram

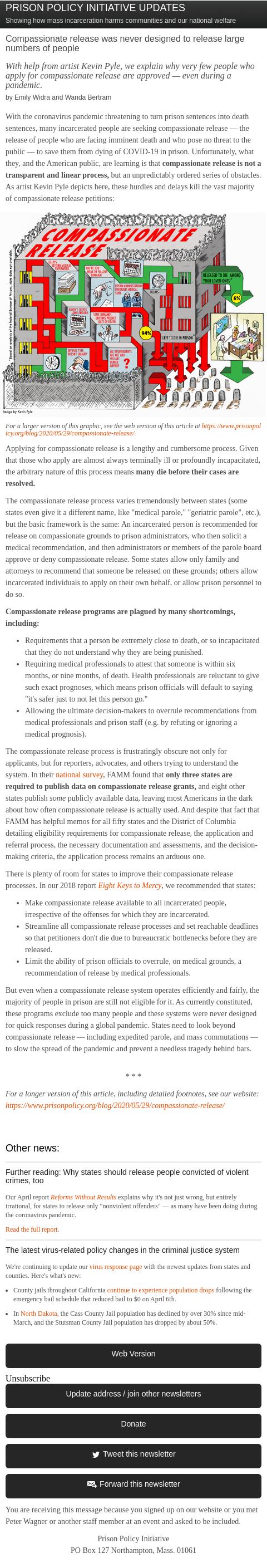

With the coronavirus pandemic threatening to turn prison sentences into death sentences, many incarcerated people are seeking compassionate release — the release of people who are facing imminent death and who pose no threat to the public — to save them from dying of COVID-19 in prison. Unfortunately, what they, and the American public, are learning is that compassionate release is not a transparent and linear process, but an unpredictably ordered series of obstacles. As artist Kevin Pyle depicts here, these hurdles and delays kill the vast majority of compassionate release petitions:

For a larger version of this graphic, see the web version of this article at [link removed]. [[link removed]]

Applying for compassionate release is a lengthy and cumbersome process. Given that those who apply are almost always terminally ill or profoundly incapacitated, the arbitrary nature of this process means many die before their cases are resolved.

The compassionate release process varies tremendously between states (some states even give it a different name, like "medical parole," "geriatric parole", etc.), but the basic framework is the same: An incarcerated person is recommended for release on compassionate grounds to prison administrators, who then solicit a medical recommendation, and then administrators or members of the parole board approve or deny compassionate release. Some states allow only family and attorneys to recommend that someone be released on these grounds; others allow incarcerated individuals to apply on their own behalf, or allow prison personnel to do so.

Compassionate release programs are plagued by many shortcomings, including:

Requirements that a person be extremely close to death, or so incapacitated that they do not understand why they are being punished. Requiring medical professionals to attest that someone is within six months, or nine months, of death. Health professionals are reluctant to give such exact prognoses, which means prison officials will default to saying "it's safer just to not let this person go." Allowing the ultimate decision-makers to overrule recommendations from medical professionals and prison staff (e.g. by refuting or ignoring a medical prognosis).

The compassionate release process is frustratingly obscure not only for applicants, but for reporters, advocates, and others trying to understand the system. In their national survey [[link removed]], FAMM found that only three states are required to publish data on compassionate release grants, and eight other states publish some publicly available data, leaving most Americans in the dark about how often compassionate release is actually used. And despite that fact that FAMM has helpful memos for all fifty states and the District of Columbia detailing eligibility requirements for compassionate release, the application and referral process, the necessary documentation and assessments, and the decision-making criteria, the application process remains an arduous one.

There is plenty of room for states to improve their compassionate release processes. In our 2018 report Eight Keys to Mercy [[link removed]], we recommended that states:

Make compassionate release available to all incarcerated people, irrespective of the offenses for which they are incarcerated. Streamline all compassionate release processes and set reachable deadlines so that petitioners don't die due to bureaucratic bottlenecks before they are released. Limit the ability of prison officials to overrule, on medical grounds, a recommendation of release by medical professionals.

But even when a compassionate release system operates efficiently and fairly, the majority of people in prison are still not eligible for it. As currently constituted, these programs exclude too many people and these systems were never designed for quick responses during a global pandemic. States need to look beyond compassionate release — including expedited parole, and mass commutations — to slow the spread of the pandemic and prevent a needless tragedy behind bars.

* * *

For a longer version of this article, including detailed footnotes, see our website: [[link removed]]

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Further reading: Why states should release people convicted of violent crimes, too [[link removed]]

Our April report Reforms Without Results [[link removed]] explains why it's not just wrong, but entirely irrational, for states to release only "nonviolent offenders" — as many have been doing during the coronavirus pandemic.

Read the full report. [[link removed]]

The latest virus-related policy changes in the criminal justice system [[link removed]]

We're continuing to update our virus response page [[link removed]] with the newest updates from states and counties. Here's what's new:

County jails throughout California continue to experience population drops [[link removed]] following the emergency bail schedule that reduced bail to $0 on April 6th. In North Dakota, [[link removed]] the Cass County Jail population has declined by over 30% since mid-March, and the Stutsman County Jail population has dropped by about 50%. Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives) [[link removed]]

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for May 29, 2020 Showing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Compassionate release was never designed to release large numbers of people [[link removed]] With help from artist Kevin Pyle, we explain why very few people who apply for compassionate release are approved — even during a pandemic. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra and Wanda Bertram

With the coronavirus pandemic threatening to turn prison sentences into death sentences, many incarcerated people are seeking compassionate release — the release of people who are facing imminent death and who pose no threat to the public — to save them from dying of COVID-19 in prison. Unfortunately, what they, and the American public, are learning is that compassionate release is not a transparent and linear process, but an unpredictably ordered series of obstacles. As artist Kevin Pyle depicts here, these hurdles and delays kill the vast majority of compassionate release petitions:

For a larger version of this graphic, see the web version of this article at [link removed]. [[link removed]]

Applying for compassionate release is a lengthy and cumbersome process. Given that those who apply are almost always terminally ill or profoundly incapacitated, the arbitrary nature of this process means many die before their cases are resolved.

The compassionate release process varies tremendously between states (some states even give it a different name, like "medical parole," "geriatric parole", etc.), but the basic framework is the same: An incarcerated person is recommended for release on compassionate grounds to prison administrators, who then solicit a medical recommendation, and then administrators or members of the parole board approve or deny compassionate release. Some states allow only family and attorneys to recommend that someone be released on these grounds; others allow incarcerated individuals to apply on their own behalf, or allow prison personnel to do so.

Compassionate release programs are plagued by many shortcomings, including:

Requirements that a person be extremely close to death, or so incapacitated that they do not understand why they are being punished. Requiring medical professionals to attest that someone is within six months, or nine months, of death. Health professionals are reluctant to give such exact prognoses, which means prison officials will default to saying "it's safer just to not let this person go." Allowing the ultimate decision-makers to overrule recommendations from medical professionals and prison staff (e.g. by refuting or ignoring a medical prognosis).

The compassionate release process is frustratingly obscure not only for applicants, but for reporters, advocates, and others trying to understand the system. In their national survey [[link removed]], FAMM found that only three states are required to publish data on compassionate release grants, and eight other states publish some publicly available data, leaving most Americans in the dark about how often compassionate release is actually used. And despite that fact that FAMM has helpful memos for all fifty states and the District of Columbia detailing eligibility requirements for compassionate release, the application and referral process, the necessary documentation and assessments, and the decision-making criteria, the application process remains an arduous one.

There is plenty of room for states to improve their compassionate release processes. In our 2018 report Eight Keys to Mercy [[link removed]], we recommended that states:

Make compassionate release available to all incarcerated people, irrespective of the offenses for which they are incarcerated. Streamline all compassionate release processes and set reachable deadlines so that petitioners don't die due to bureaucratic bottlenecks before they are released. Limit the ability of prison officials to overrule, on medical grounds, a recommendation of release by medical professionals.

But even when a compassionate release system operates efficiently and fairly, the majority of people in prison are still not eligible for it. As currently constituted, these programs exclude too many people and these systems were never designed for quick responses during a global pandemic. States need to look beyond compassionate release — including expedited parole, and mass commutations — to slow the spread of the pandemic and prevent a needless tragedy behind bars.

* * *

For a longer version of this article, including detailed footnotes, see our website: [[link removed]]

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Further reading: Why states should release people convicted of violent crimes, too [[link removed]]

Our April report Reforms Without Results [[link removed]] explains why it's not just wrong, but entirely irrational, for states to release only "nonviolent offenders" — as many have been doing during the coronavirus pandemic.

Read the full report. [[link removed]]

The latest virus-related policy changes in the criminal justice system [[link removed]]

We're continuing to update our virus response page [[link removed]] with the newest updates from states and counties. Here's what's new:

County jails throughout California continue to experience population drops [[link removed]] following the emergency bail schedule that reduced bail to $0 on April 6th. In North Dakota, [[link removed]] the Cass County Jail population has declined by over 30% since mid-March, and the Stutsman County Jail population has dropped by about 50%. Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives) [[link removed]]

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor