|

|

Is the Revolt of the Public Over?

The public may still be revolting, but digital media is now ushering in the restoration of institutional control over society

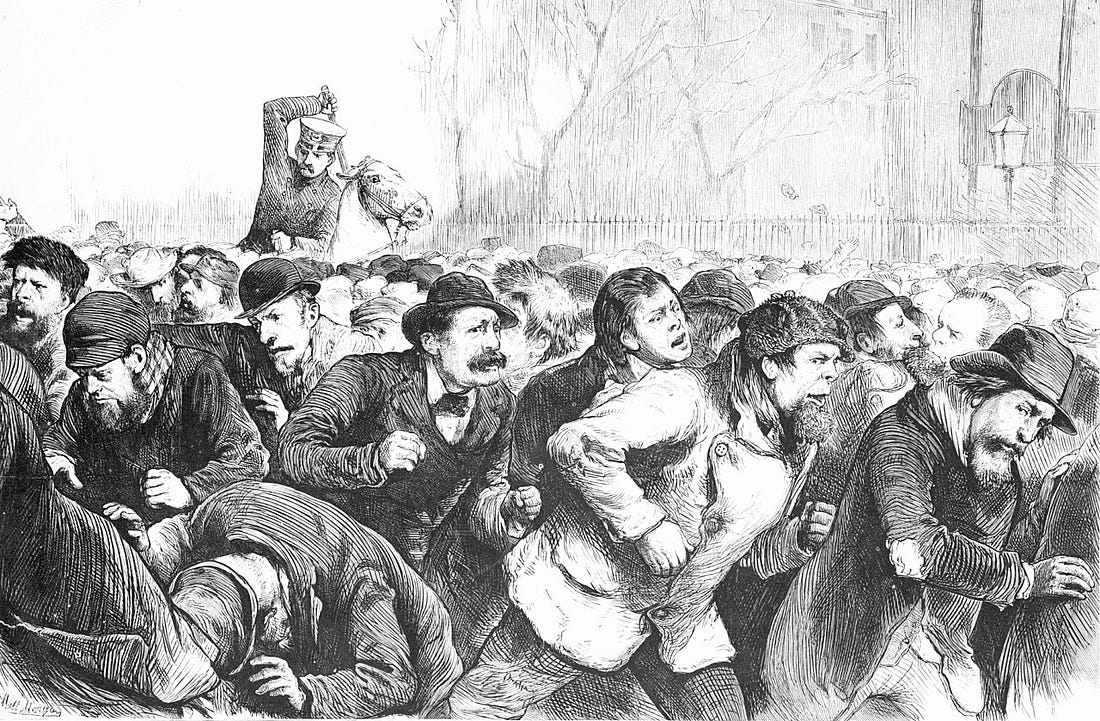

Donald Trump’s electoral win in November marked a turn in the political tide, one that looked like a turn against the elites. This victory of populist sentiment seems to be a continuation of Martin Gurri’s “Revolt of the Public.” According to Gurri, the blogosphere and social media in the early 2010s challenged the institutional order by giving people ample opportunity to inform each other. The internet disrupted the power balance between the public and the elites, causing a “crisis of authority,” in Gurri’s words. Institutions weakened and the power of the public rose, leading to the anti-establishment wave around the world—from the Twitter revolutions of 2009-2011 to Brexit and Trump’s initial rise to political power in 2016.

Institutions simply did not know how to deal with the disruptive power of the internet. As Peter Thiel put it in 2015, this was a “world in which bits were unregulated and atoms were regulated.”

But 10 years later, do these conditions still exist? Are bits as unregulated as they were in the early 2010s? Hardly so. On the contrary, institutions often struggle to regulate atoms, but they have learned to regulate bits. A vivid example: U.K. authorities flounder with finding solutions to the country’s immigration issues but have started arresting people for social media posts about it.

Put simply, the internet’s power has reversed: It now threatens the public, not institutions. This is happening worldwide, regardless of political regime. The elites forced digital platforms to create massive censorship machines to combat foreign interference, fake news, vaccine hesitancy and, eventually, political dissent. Prominent figures have called for criminalizing more online behavior or introducing digital ID to better control people’s actions. Institutions have learned not only to neutralize the disruptive power of the internet but also to harness its capacity for subjugation.

Analyzing these symptoms after the arrest of Telegram’s CEO Pavel Durov in France last summer, I wrote that the revolt of the public is over. Then Donald Trump returned to power. His and his allies’ anti-establishment resolve seemed to showcase that the revolt of the public continues. Referring to my thesis about the restoration of institutions, Martin Gurri wrote in November following the election: “We are living through a moment of revolt, not reaction. …That is to say, government censorship failed completely: The public was still in command of the strategic heights above the information landscape.”

A significant part of the public does express an anti-establishment sentiment in the U.S. and worldwide. Yet, as counterintuitive as it may seem after Trump’s second win, the internet now empowers institutions rather than disrupting them. Institutions keep failing on so many fronts, but with the public? No, they are regaining control over the public, rebellious or not.

Four Factors Ending the Revolt of the Public

For years, Martin Gurri and I saw things so similarly that he once called us “intellectual doppelgängers.” Yet, we approached the subject from different angles. Martin’s focus was political—how the internet disrupted the balance of power between elites and the public. My perspective was media-ecological—how social media turned online activity into political activism. Media ecology has changed drastically since the Twitter revolutions of the early 2010s. However dear Martin is to me, media ecology is dearer. And media ecology says that the revolt of the public is over and the restoration of institutional power has begun.

Here are four environmental factors that brought this era to an end.

Factor 1: The global demographic transition to the digital realm, which caused the revolt of the public in the first place, is now complete.

The demographic transition to digital occurred in two distinct waves. First, social media was adopted by the young, educated, urban and progressive in the late 2000s and early 2010s. This led to Twitter revolutions everywhere, from the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street. Soon, however, social media proliferated further and empowered older, less urban, less educated and more conservative demographics, leading to the conservative rebound and the global right turn in the late 2010s, exemplified by Brexit, Trump, Bolsonaro and so on.

With this, the demographic resource to be politicized by social media was exhausted. There will be no significant demographic arrivals to fuel the digital transition that once ignited the clash between the digitized public and old institutions. Of course, new generations of youngsters and new media platforms for them can still cause political turbulence, but this will be generational—Turgenev’s “Fathers and Sons” issues, not a global demographic media transition. That’s now complete.

Factor 2: Old institutions absorbed rebellious elements from the public, transforming them into institutional loyalists and champions.

During the Digital Rush of the early 2010s, old institutions needed to switch to digital, too, and so they began courting early social media adopters, who were mostly progressive at the time. As a result, a significant portion of academia, journalists, pop culture and other “normally” rebellious strata—even activists—were co-opted and corrupted by the establishment, creating a chimeric hybrid of establishment and activism.

This could not last—no society has the resources to rest on disruption for too long. With the arrival of the second, more conservative demographic wave on social media, the progressive disruption eventually encountered a conservative backlash, which is now disrupting the previously disrupted through a new round of political turmoil. In the U.S., institutions will now likely absorb contrarians from the right, as exemplified by the Trump administration. This is becoming more of a rotation of the elites rather than a revolt of the public, even though the public’s revolt has had some residual impact on the process: The demolition of bureaucracy and the exposure of its expenses are cheered by the crowd that propelled Trump to power.

Factor 3: The class of professional abusers of the internet emerged, inciting growing public frustration and a demand for harsher control over information.

The internet that spurred the revolt of the public in the late 2000s was innocent—unspoiled by fake actors and sophisticated manipulations. The first social media users were educated and mostly considerate people. However, with the growth of the user base, the quality of online conversation inevitably degraded.

The enshittification of the internet, as Cory Doctorow calls it, was dramatically amplified by its “organic” capacity for professional abuse. It began in 2011, or even earlier, when the U.S. military deployed an “online persona management service” that allowed one operator “to control up to 10 separate identities from all over the world.” After the Russian election meddling in 2016, it became known as fake accounts and bot farms.

In 2012, as the media reported with naïve admiration, the “digital wizards” behind Barack Obama’s reelection campaign built a vast digital operation that combined a “unified database on millions of Americans with the power of Facebook to target individual voters.” At the time, it was called the “power of friendship.” After the scandal with Facebook and Cambridge Analytica in 2018, it is now known as social media profiling and the manipulation of personal data.

In the late 2010s, fake accounts, trolls, bot farms and the harvesting of personal data became major issues, changing the internet from a beacon of democracy into a poisoned well. Not only was the problem itself real, but it also led to growing societal frustration and created a widespread demand for institutions to tighten control over information. Institutions received carte blanche … from the public.

Factor 4: Algorithms emerged, leading to centralized, controllable digital platforms.

The essential condition for the revolt of the public was not only the public’s awakened awareness regarding the elites but also the elites’ inability to deal with the dispersed nature of protests. Old institutions, however powerful the tools of oppression they possessed, simply could not catch the organizers of the revolt, as there were none. It was like a fight between a bear and a beehive: A bear can take down a bee, or even many bees, but never the hive.

Algorithms improved content relevance for both users and advertisers, creating the incredible opportunity for customized ad targeting with precision and scale unimaginable in old media. As Douglas Rushkoff put it in 2019, “The Internet went from town hall to shopping mall.” The amorphous blogosphere evolved into centralized social media platforms, which are corporate entities. Institutions are well-versed in dealing with corporations, as corporations belong to the institutional world.

Carrying the risks of regulatory retaliation and profit loss, digital corporations readily complied with the elites’ demands. To extend the bear-bee metaphor, the bear has hired beekeepers. Digital platforms cannot host revolutions; they cannot tolerate any unsanctioned activity for long—ask Telegram’s Durov, who was arrested in France, essentially for noncompliance. The revolt of the public has largely lost its online hosting.

The Fire Burned Out, the Phoenix Reborn

In the 2010s, the internet enabled a progressive revolution followed by a conservative counter-revolution; both were subsequent parts of the revolt of the public. This phase is over because digital media ecology has changed. Institutions have adapted and rebuilt themselves to address digital challenges and capitalize on digital opportunities. Digital platforms have become the new gatekeepers, far more powerful than any previous tools of elite discourse control, whether old media, academia or Hollywood.

Who controls the platforms controls the public. This new landscape is evident everywhere in the world. Only the “land of the free” seemingly demonstrates a major setback by re-energizing the revolt of the public with the recent election of Trump.

Or does it?

The Donald Trump of 2016 was an outsider. His rule was superficial, based more on rhetoric and appeal to the masses in the fashion of a TV show, but through tweeting. But today, though still with a strong personal touch, he actively engages with institutions. His cadres control Republican Party bureaucracy. Some of his appointees might appear counter-elite, but collectively, they represent a pretty systemic approach to the disruption, or rather demolition, of the previous bureaucratic arrangements. The assault on bureaucracy is carried out by creating yet another bureaucratic institution—the Department of Government Efficiency. A part of the elites—including Big Tech, financial leaders, law enforcement and local governments, whatever their motives were—has joined Trump, strengthening his institutional power.

To the Gramscian strategy of infiltrating institutions, carried out by progressives over a decade, Trump responds with “flood the zone” tactics, issuing an avalanche of directives to overwhelm and paralyze opponents and disrupting everything else along the way. However, the battle is now fought on institutional grounds. It’s not the public’s assault on elites; it’s the fight for control—over power and the public—between the right and the left (or what’s left of the left, mostly in the media). And digital media now readily offer the means for such control. Trump’s second tenure may be a counter-elite revolution leading to political turmoil, but it is no longer a revolt of the public.

Moreover, the redesign of institutions under Trump could result in a more authoritarian institutional grip. The digital environment now favors not more freedom but more control. The most probable outcome of merging Western democracies with digital control will be anarcho-totalitarianism. State control will tighten where it’s easier to enforce with new digital tools, while weakening where the state lacks will or ability. The U.K. is already on this path. The U.S. may follow, though in a different political context, where the public is subjugated not to progressive narratives but to reactionary ones.

Revising the Revolt

Of course, the claim that the public’s revolt is over is an invitation to debate. Some events send mixed signals. Is Elon Musk freeing X from progressive-bureaucratic control and handing it over to support Trump a sign of the public’s revolt or institutional restoration? Does Mark Zuckerberg ending censorship on Facebook support the concept of revolt or the idea of power restoration? Digital speech in the U.S. might seem freer than it was two years ago, but this reflects the decisions of the digital oligarchs who own the platforms. They can easily tighten the screws as they please or as the political climate dictates.

This was impossible during the classic revolt of the public, as described by Gurri in 2014. Grassroots online activity still fuels the process, but it is contained on digital platforms and framed by algorithms executing corporate orders. Platforms have tamed the revolting public and subjected it to the game of institutions.

Gurri sees the signs of Trump’s institutionalization as well. In one recent essay, he states that the revolt continues, but at the same time he admits that it “gains legitimacy” and the populism behind it becomes “programmatic.” This is something truly new: The classic revolt of the public lacked both legitimacy and political programs. It could not elaborate policies; its only “policy” was anti-establishment nihilism. This is why the revolt of the public was regime-ignorant: In the early 2010s, it rebelled against Hosni Mubarak, Barack Obama or Vladimir Putin indiscriminately.

This time, however, as Gurri observes, populism “has begun to evolve a governing program,” and perpetual nihilism has turned into an action plan. Essentially, Trump’s counter-elite project seeks to remake institutions after 10 years of progressive affiliation and unchecked bureaucratic growth. As Gurri concludes his analysis, “it would be the crowning irony of Trump’s improbable trajectory if the motley collection of pirates and adventurers presently around him turns out to be the next American ruling class.”

That’s the point: The rotation of the elites is the elites’ business, not the public’s. The public is involved only to provide the proverbial “mandate” and carry some echoing legacy of the 2010s’ digital revolt that enabled Trump’s first win.

Fascinatingly, six years ago, Gurri already foresaw the possibility of digital institutionalization. In the second edition of “The Revolt of the Public” in 2018, he added a chapter with predictions—or, rather, hopes. He wrote: “Once government goes digital, it becomes possible to alter its structure, even redirect its purpose.” Ideally, this could be the outcome of fighting bureaucracy, if reforming the administration were to end up in good hands. Replacing a part of the government with AI-driven digital services is viable; it will increase efficiency and decrease cost.

“The revolt of the public, as I envision it, is a technology-driven churning of new people and classes,” wrote Gurri in 2018. Hoping for the emergence of new principles for legitimacy, hierarchy and authority, he essentially predicted the institutional restoration in a new, digitally modified society. We are certainly set to witness exactly this, for better or worse—the completion of society’s restructuring after the turbulent decade of digital transition. Martin Gurri, the oracle of the revolt of the public, saw it coming.

You’re currently a free subscriber to Discourse .