Email

Round and Round

| From | Trygve Hammer <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Round and Round |

| Date | January 12, 2025 11:15 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

The intel officer was pretty sure the hand-labeled VHS tapes in the TV stand were porn. There were dozens of them with labels like, ”1988 U.S. Open,” and “1990 Daytona 500.”

I told him that I found it hard to imagine anyone watching porn in the common area of a bachelor officer quarters.

“Sir, you don’t know some of these Southern boys,” he said. “They’re freaks.” He put in one of the tapes and hit ‘play.’ On the screen, numbered cars with corporate logos followed a pace car while announcers droned on about some guy in the whatever make of car who just missed the pole position and had finished 2nd in some other race to start the season. The intel officer fast-forwarded in search of the hidden porn, but where he had suspected a bunch of in-and-out, there was just a lot of round-and-round.

Another captain walked in: “Winston 500! What year is that?”

“The lieutenant’s just hunting for hidden porn,” I said. “You would actually sit and watch this?”

“Are you kidding? I’m from Winston-Salem,” he said, as if that explained everything.

“I told you,” I said to the intel officer. “Some of these Southern boys are freaks.”

There was more down time than I had anticipated between major training events on that deployment, and it wasn’t unusual during the slow periods to enter the common area and find Marines watching those recorded car races and golf tournaments. Not being a golfer or a person with a great love for or hatred of any driver or car manufacturer, I filled my unstructured time with books.

One of those books was Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards. As I read the book and completed the exercises, I progressed from kindergarten stick men to a passable self-portrait. I may have gained some skill in handling a pencil, but the main thing I had learned was how to see in a different way and avoid labeling the objects I was trying to draw.

Once we label something, our minds stop seeing lines and shadows and negative spaces and their relationship to each other. Instead, we see our personal stored symbols for hand or ear or koala or daffodil. Labels keep us from seeing things as they really are. Instead, we see our personal cartoon version of reality.

“People are too complicated to have simple labels,” wrote Philip Pullman in The Amber Spyglass. So are groups of people. We gather under the same banner or in the same house of worship or school of philosophy, but few of us see our chosen label in exactly the same way. And yet it is easy to look at those under an opposing label and see complete homogeneity. This causes some to demand purity within the group. “No true Republican would believe that,” they might say, for example. “You’re a cotton-pickin’ RINO!”

These days, some folks just can’t seem to help slapping an ideological label on anything they don’t like or anything they don’t understand but have been told they shouldn’t like. CRT is Marxism! SEL is communism! Neither of these things are true or even make any sense. This is simple name-calling. It is used to end the discussion, avoid the details, and keep people from looking any deeper than the label. It often works, because we are lazy—as nature intended—and we love shortcuts.

When I was teaching—especially substitute teaching—I used to play a game called “What’s in the box?” I borrowed the idea from the book Improv Wisdom by Patricia Ryan Madson, and it was usually both fun and a good filler for unstructured time. (A horror movie for substitute teachers would be titled Unstructured Time.) I would begin the game by describing a box and showing the dimensions with my hands. I would shake the box and listen, maybe remark on the weight of it, and then set it on my desk, lift the make-believe lid and report on the contents. It might be a cotton ball or an iguana or a miniature model of Jurassic Park complete with live miniature dinosaurs. After a few examples like that, the students would pass the box around the room and each one would report what he or she found inside. There were bunnies and squirrels and hand grenades and rattlesnakes, lots of rattlesnakes.

For one fourth grader the box contained a dragon from Game of Thrones. “A baby one like when they first come out of the fire,” he said. My first thought was that the baby dragons on Game of Thrones emerge from a funeral pyre perched on a naked woman, and that wasn’t even close to the top reason why a fourth grader should not be watching Game of Thrones. There were the whorehouses, the incest, the graphic violence . . .

“Amazing!” I said. “Next!”

I could have avoided the Game of Thrones problem by labeling the box “Things that are real and fit in the box,” but that would have stifled creativity and there would have been no rhinos or giraffes or grizzly bears or planets.

Now imagine trying to come up with a solution to some problem in our society, but you are only allowed to draw from a box marked “progressive” or “conservative” or “free-market solutions” or “government solutions.” From the start, you would be limited in the kinds of solutions you might find, and possibly confused, because these ideological labels tend to be a bit subjective anyway.

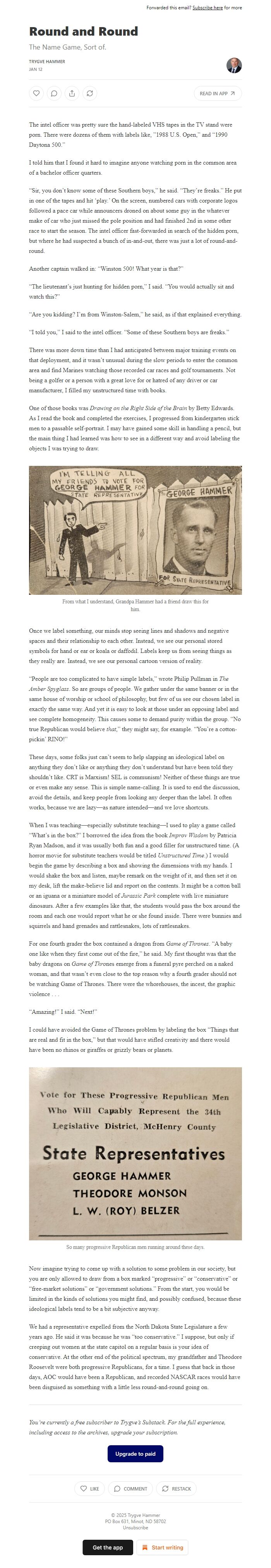

We had a representative expelled from the North Dakota State Legislature a few years ago. He said it was because he was “too conservative.” I suppose, but only if creeping out women at the state capitol on a regular basis is your idea of conservative. At the other end of the political spectrum, my grandfather and Theodore Roosevelt were both progressive Republicans, for a time. I guess that back in those days, AOC would have been a Republican, and recorded NASCAR races would have been disguised as something with a little less round-and-round going on.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

The intel officer was pretty sure the hand-labeled VHS tapes in the TV stand were porn. There were dozens of them with labels like, ”1988 U.S. Open,” and “1990 Daytona 500.”

I told him that I found it hard to imagine anyone watching porn in the common area of a bachelor officer quarters.

“Sir, you don’t know some of these Southern boys,” he said. “They’re freaks.” He put in one of the tapes and hit ‘play.’ On the screen, numbered cars with corporate logos followed a pace car while announcers droned on about some guy in the whatever make of car who just missed the pole position and had finished 2nd in some other race to start the season. The intel officer fast-forwarded in search of the hidden porn, but where he had suspected a bunch of in-and-out, there was just a lot of round-and-round.

Another captain walked in: “Winston 500! What year is that?”

“The lieutenant’s just hunting for hidden porn,” I said. “You would actually sit and watch this?”

“Are you kidding? I’m from Winston-Salem,” he said, as if that explained everything.

“I told you,” I said to the intel officer. “Some of these Southern boys are freaks.”

There was more down time than I had anticipated between major training events on that deployment, and it wasn’t unusual during the slow periods to enter the common area and find Marines watching those recorded car races and golf tournaments. Not being a golfer or a person with a great love for or hatred of any driver or car manufacturer, I filled my unstructured time with books.

One of those books was Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards. As I read the book and completed the exercises, I progressed from kindergarten stick men to a passable self-portrait. I may have gained some skill in handling a pencil, but the main thing I had learned was how to see in a different way and avoid labeling the objects I was trying to draw.

Once we label something, our minds stop seeing lines and shadows and negative spaces and their relationship to each other. Instead, we see our personal stored symbols for hand or ear or koala or daffodil. Labels keep us from seeing things as they really are. Instead, we see our personal cartoon version of reality.

“People are too complicated to have simple labels,” wrote Philip Pullman in The Amber Spyglass. So are groups of people. We gather under the same banner or in the same house of worship or school of philosophy, but few of us see our chosen label in exactly the same way. And yet it is easy to look at those under an opposing label and see complete homogeneity. This causes some to demand purity within the group. “No true Republican would believe that,” they might say, for example. “You’re a cotton-pickin’ RINO!”

These days, some folks just can’t seem to help slapping an ideological label on anything they don’t like or anything they don’t understand but have been told they shouldn’t like. CRT is Marxism! SEL is communism! Neither of these things are true or even make any sense. This is simple name-calling. It is used to end the discussion, avoid the details, and keep people from looking any deeper than the label. It often works, because we are lazy—as nature intended—and we love shortcuts.

When I was teaching—especially substitute teaching—I used to play a game called “What’s in the box?” I borrowed the idea from the book Improv Wisdom by Patricia Ryan Madson, and it was usually both fun and a good filler for unstructured time. (A horror movie for substitute teachers would be titled Unstructured Time.) I would begin the game by describing a box and showing the dimensions with my hands. I would shake the box and listen, maybe remark on the weight of it, and then set it on my desk, lift the make-believe lid and report on the contents. It might be a cotton ball or an iguana or a miniature model of Jurassic Park complete with live miniature dinosaurs. After a few examples like that, the students would pass the box around the room and each one would report what he or she found inside. There were bunnies and squirrels and hand grenades and rattlesnakes, lots of rattlesnakes.

For one fourth grader the box contained a dragon from Game of Thrones. “A baby one like when they first come out of the fire,” he said. My first thought was that the baby dragons on Game of Thrones emerge from a funeral pyre perched on a naked woman, and that wasn’t even close to the top reason why a fourth grader should not be watching Game of Thrones. There were the whorehouses, the incest, the graphic violence . . .

“Amazing!” I said. “Next!”

I could have avoided the Game of Thrones problem by labeling the box “Things that are real and fit in the box,” but that would have stifled creativity and there would have been no rhinos or giraffes or grizzly bears or planets.

Now imagine trying to come up with a solution to some problem in our society, but you are only allowed to draw from a box marked “progressive” or “conservative” or “free-market solutions” or “government solutions.” From the start, you would be limited in the kinds of solutions you might find, and possibly confused, because these ideological labels tend to be a bit subjective anyway.

We had a representative expelled from the North Dakota State Legislature a few years ago. He said it was because he was “too conservative.” I suppose, but only if creeping out women at the state capitol on a regular basis is your idea of conservative. At the other end of the political spectrum, my grandfather and Theodore Roosevelt were both progressive Republicans, for a time. I guess that back in those days, AOC would have been a Republican, and recorded NASCAR races would have been disguised as something with a little less round-and-round going on.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a