|

|

Sinking the Clipper Chip

An influential tech debate from the 1990s reveals still-relevant lessons about the tensions between tech innovation, government efficiency and privacy

With AI becoming increasingly popular, critics of the new technology have cited concerns about privacy and data security. Such objections are nothing new: Thirty years ago, increasingly widespread use of the internet prompted many of the same criticisms. In the early 1990s, as personal computing and web browsers connected ever more Americans, the U.S. government unveiled a controversial policy proposal that would ignite some of the most consequential debates about technology, privacy and democracy in recent decades: the clipper chip. Introduced in 1994, the clipper chip was a device designed by the National Security Agency to encrypt telephone calls and telecommunications while allowing the government to access these ostensibly private communications.

The proposal sparked fierce opposition from technologists, civil liberties advocates and business leaders. Sometimes remembered as the “crypto wars” of the 1990s, these debates revealed deep tensions between national security and individual privacy, foreshadowing many of the pressing challenges in governing technology today. Three decades later, what can we learn from one of the most contentious episodes in the history of surveillance, privacy and political conflict in the digital world?

A Technological Policy Raises Major Concerns

The clipper chip was unveiled in 1993 as a catch-all encryption tool by the NSA and the Clinton administration. In broad strokes, the NSA designed the new encryption hardware with the ostensible goal of giving consumers privacy—but with the dubious addition of a backdoor to allow the government to surveil civilian traffic. The administration, for its part, would use export controls to cajole manufacturers into installing it. These efforts would standardize tech governance policies that too often appeared as a confusing patchwork.

The idea for the clipper chip came to policymakers during the George H.W. Bush administration. But President Bush did not implement the clipper chip, leaving the policy in the lurch as a result of a presidential transition and the turnover it created. In 1992, officials within the FBI warned that the presidential transition itself created a potential problem for the chip’s advocates: What if the scheme came to light?

In a memo to FBI Director William S. Sessions in December 1992, analyst J.R. Davis warned that proceeding with installation of the clipper chip had several “potential pitfalls,” the most serious of which was the possibility that “the use of the ‘exploitable’ chip could surface publicly during the transition period or shortly after the Clinton administration arrives.” This would, Davis feared, potentially lead the new administration to “disavow” the chip rather than move forward “with us in a consolidated effort to convince Congress and the public of the merits of our position.” Davis’ warning, though prescient, did not shape government policy.

In the end, proposals for the clipper chip gained traction because of government and FBI worries that they would not be able to monitor information flows and surveil citizens because of the rapid evolution and increasing sophistication of communications encryption and digital technology. The clipper chip itself was designed for use in secure telephones, while a related technology, the capstone chip, would be used for electronic data. Both would scramble data packets sent through telephone lines or the internet, while chips at receiving telephones or computers would unscramble the data. Using a technique called “key escrow,” however, agents within the federal government would hold a secret key for each manufactured chip—thus ensuring access in the event of a national security emergency or during routine law enforcement practice.

The Coalition Against the Clipper Chip

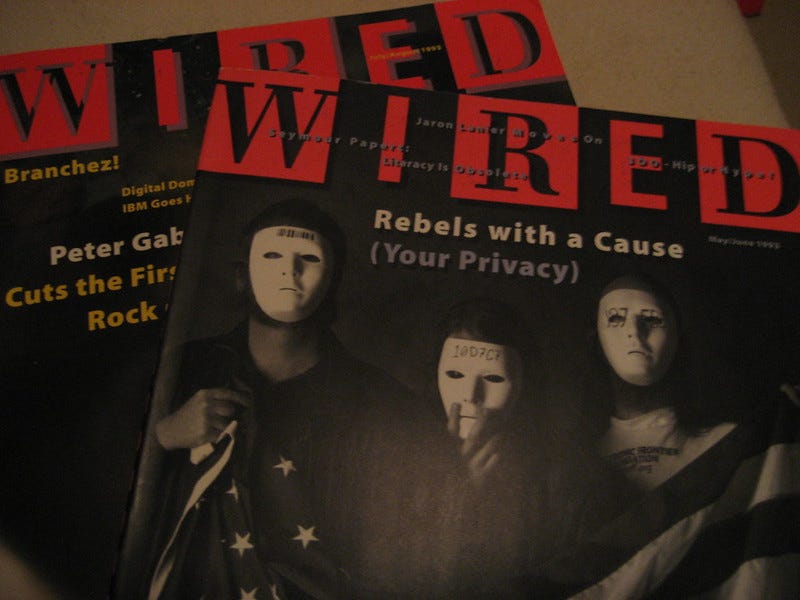

Resistance to the clipper chip united an eclectic coalition. Academics and critics quickly identified flaws. Civil libertarians decried the backdoor access as a fundamental violation of privacy and a potential tool for government overreach. Technology experts warned that centralizing encryption keys could create vulnerabilities, and business leaders feared the chip would harm American competitiveness in the global technology market. As a result, the clipper chip became a flashpoint for broader concerns about surveillance in the digital age.

Civil liberties organizations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the American Civil Liberties Union led the charge, emphasizing the risks the chip posed to constitutional rights. Professional organizations amplified these critiques: For example, Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility collected more than 50,000 signatures on a petition opposing the chip.

Corporate America also entered the fray, with major technology firms including Apple, IBM and Microsoft joining the opposition. These companies argued that adopting the clipper chip would hinder innovation and put U.S. businesses at a disadvantage in the international market, where clients valued secure communication free from government interference.

This opposition further extended to technologists and academics, many of whom warned of the chip's technical flaws. The NSA’s proprietary algorithm, kept secret from independent review, raised concerns about its efficacy and potential exploitation. Critics pointed out that determined adversaries could bypass the system altogether by using alternative encryption tools, rendering the clipper chip ineffective against sophisticated criminals and foreign agents.

Cypherpunks and Grassroots Activism

Among the most vocal opponents of the clipper chip were the cypherpunks, a decentralized group of technologists, cryptographers and activists who viewed strong encryption as essential for protecting privacy and enabling free expression in the digital age. As New York Times journalist Steven Levy described the cypherpunks in the 1990s, the group was a “loose confederation” of eccentric “high-tech rabble-rousers” who cohered in email listservs and online forums.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, former Intel engineer Timothy May was actively discussing the politics of encryption with other programmers and hackers such as Eric Hughes, John Gilmore and Jude Milhon. These allied technicians regularly held discussion groups on politics and technology in the Bay Area. Eventually, the group decided to take its conversations online. By 1992, the cypherpunks had formed an email listserv for continued discussion. It was Milhon who, at one of the first meetings in 1992, merged the words “cipher,” the basic unit of encryption, and “cyberpunk,” the new slang for scruffy users of high tech, into “cypherpunk.”

The cypherpunks’ mailing list flourished throughout the 1990s. Its reach peaked near 2,000 subscribers in the late 1990s and included many influential programmers, hackers, mathematicians, entrepreneurs, technologists and journalists, including Julian Assange. The listserv was an influential forum from the start. In time, as the cypherpunks expanded their ranks, the community coalesced around beliefs in the importance of privacy and anonymity and the danger of censorship and surveillance.

Eric Hughes, a founding member of the group, articulated this vision in his 1993 “Cypherpunk’s Manifesto,” declaring, “We must defend our own privacy if we expect to have any.” In time, this grassroots movement helped mobilize public sentiment against the clipper chip. Online forums, mailing lists and petitions spread awareness and galvanized opposition, demonstrating how digital networks could be harnessed for political activism.

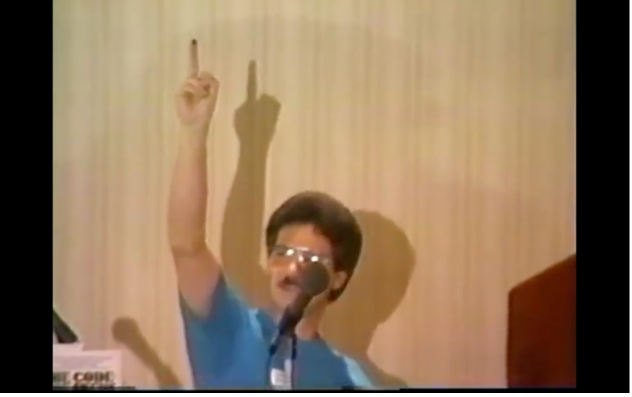

In August 1994, more than 1,000 hackers, computer scientists, consultants and observers gathered in New York City’s Hotel Pennsylvania for the first annual gathering of Hackers on Planet Earth (HOPE). Attendees learned about topics such as amateur radio, lockpicking, ID fabrication and how to “Control the World with Your PC.” HOPE sought to spark the “hacker spirit” within society in a computerized age. Thus, at the 1994 HOPE conference, cypherpunks convened a two-hour panel to dissect the clipper chip’s technical and political implications. Their disdain was evident when one panelist famously raised a clipper chip on his middle finger, symbolizing the community’s defiance.

|

The Clinton Administration’s Defense and Retreat

Facing mounting criticism, the Clinton administration sought to defend the clipper chip as a necessary compromise between privacy and security. Officials emphasized that the system was voluntary for American technology manufacturers and promised that the escrowed keys would be securely managed by trusted government agencies such as the Department of Commerce.

Yet these assurances failed to quell opposition. Critics labeled the “voluntary” framing disingenuous, noting that the U.S. government’s International Traffic in Arms Regulations had long treated any technology or code that encrypted information as a potential weapon—and therefore subject to strict export controls. Thus, the government effectively held the tools to compel compliance with any company wary of installing the clipper chip. Moreover, public trust in the NSA and FBI was low, and revelations about domestic surveillance abuses only deepened skepticism.

The administration also struggled to address the technical critiques and win over critics in the business community. A report from the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) highlighted the chip’s potential vulnerabilities. Moreover, the ACM suggested that the administration outright withdraw the clipper chip proposal, create “open forums” for discussing policy developments in cryptography, and prioritize policy advantages for U.S. manufacturers and privacy for its citizens. As pressure mounted, officials postponed the rollout and initiated reviews, but the clipper chip’s reputation was irreparably damaged.

Meanwhile, Bell Labs researcher Matt Blaze discovered vulnerabilities in the clipper chip’s design that the NSA had left undisclosed. In the private sector, industry associations including the Information Technology Association of America, Computer and Business Equipment Manufacturers Association, Business Software Alliance, Software Publishers Association and Information Systems Security Association all opposed the clipper chip as technologically cumbersome and economically infeasible.

Lessons from the Clipper Chip Debate

By 1996, the clipper chip had been roundly panned as bad policy, poor technology and a burden for American business. The proposal was abandoned in the face of overwhelming opposition. Its demise marked a victory for the coalition of technologists, activists and industry leaders who had championed privacy and innovation over government surveillance.

The clipper chip debates revealed the challenges of balancing security and liberty in the digital age. They underscored the risks of imposing top-down technological solutions without transparency or public trust. They also highlighted the power of grassroots mobilization and the importance of diverse coalitions in shaping technology policy.

Governments around the world continue to grapple with the “going dark” problem, where widespread encryption complicates law enforcement’s ability to access communications. Meanwhile, privacy advocates warn against proposals for backdoors, citing the clipper chip as a cautionary tale.

In light of the recent Chinese hacker group Salt Typhoon’s wiretaps of AT&T and Verizon, which exploited backdoors in the telecommunications infrastructure, lessons from the clipper chip are as relevant as ever: In computer security, it is best to assume there’s no such thing as a tool only the good guys will use.

You’re currently a free subscriber to Discourse .