Email

NEW DATA: Fewer people are in contact with police, but racial disparities persist

| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | NEW DATA: Fewer people are in contact with police, but racial disparities persist |

| Date | January 7, 2025 3:44 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Racial disparities in arrest, police misconduct, and use of force persist.

Prison Policy Initiative updates for January 7, 2025 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Despite fewer people experiencing police contact, racial disparities in arrests, police misconduct, and police use of force continue [[link removed]] New Bureau of Justice Statistics data reveal that concerning trends in policing persisted in 2022, even while fewer people interacted with police than in prior years. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra

Almost 50 million people reported contact with police in 2022, reflecting the fewest number of police encounters with the public since 2008 [[link removed]]. But just because the sheer number of police interactions was lower than it has been in decades does not mean the problems with our nation’s fraught system of policing are solved. The newest report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Public-Police Contact series [[link removed]] reveals that racial disparities in police interactions, misconduct, and use of force remained pervasive in 2022. In this briefing, we examine the latest data showing that Black people continued to face higher rates of enforcement actions, police misconduct, and use of force despite relatively similar rates of contact with police. These new data also show heightened levels of police interaction and use of force against young adults, and a growing rate of use of force against women, warranting further investigation of trends in policing.

Millions of people contacted police, but mostly not to report crime

Most police contacts are initiated by residents: almost 30 million people initiated contact with police in 2022. However, only half of these people ever reported possible crimes. More often, they were seeking help. Among people who initiated their most recent contact with police, 25% were reporting a non-crime emergency (like a medical emergency or car accident they weren’t involved in), 26% were reporting other non-emergencies (including requests for custody enforcement or other services, accidental 911 calls, asking for directions, and looking for lost pets), and 3% were block watch-related contacts.

Although we have little national context regarding the reasons for resident-initiated police contact and the outcome of those interactions, a 2022 analysis of over 4 million 911 calls for police service in eight major U.S. cities [[link removed]] found that only 4% of calls were related to violent offenses (including gunshot reports); the majority of calls for service did not result in any action related to law enforcement or crime prevention. In other words, most calls to the police would be best directed elsewhere if communities had the necessary funding and capacity. Given how dangerous seemingly innocent police interactions can be [[link removed]], this is a sign of the need for community investments and government infrastructure that are better suited to address concerns about quality of life (e.g., noise, animals, or disorderly behavior), health (mental, physical, and behavioral), and vehicle and traffic issues — some of the most common themes of 911 calls for service in the 2022 study.

Traffic stops remain the most common reason for police-initiated contact across all demographics

In 2022, fewer than 1 in 5 U.S. residents over the age of 16 (or 18.5%) had face-to-face contact with police, down from 24% [[link removed]] in 2018 [[link removed]]. The Bureau of Justice Statistics attributes this decline to a decrease in the number of traffic stops, which fell by 33% from over 24 million to 16.2 million over this same four-year period. Despite this decline, traffic stops were still the most common type of police-initiated contact, regardless of gender, race, or age: more than 12 million drivers were stopped by police in 2022, and these stops are often fraught with racial bias [[link removed]] and violence [[link removed]].

Racial disparities pervade police encounters

White people were far more likely than Black people, Hispanic people, and Asian people to initiate contact with the police, for reasons including to report possible crimes and emergencies, to participate in block watches, or to seek other kinds of help from police. In fact, 2 out of every 5 (42%) U.S. residents over the age of 16 who had any police contact in 2022 were white people initiating police contact.

On the other hand, people of color — and Black people in particular — were more likely to experience police-initiated contact, including street stops, traffic stops, and arrests. Forty-five percent of Black and Hispanic people who had any contact with the police were approached by police, compared to 40% or less of white people, Asian people, and people of other races. Not only were Black people disproportionately likely to experience traffic stops and arrests, but they were also more likely to experience enforcement actions from police during street stops and traffic stops, and to face police misconduct and use of force:

Street stops: While the survey found little racial or ethnic difference in the likelihood of being stopped on the street by police, Black people were somewhat more likely to face enforcement actions from police in street stops: 18% of Black people stopped received a warning compared to 15% of white people, and 8% of Black people stopped were searched or arrested compared to 6% of white people. Hispanic people were far less likely (11%) to receive an enforcement action when stopped than white (24%) or Black people (25%).

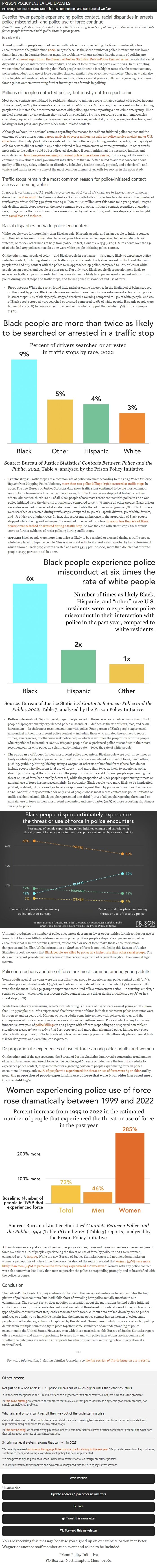

Traffic stops: Traffic stops are a common site of police violence: according to the 2023 Police Violence Report from Mapping Police Violence, more than 100 police killings (13%) occurred at traffic stops [[link removed]] in 2023. The new Bureau of Justice Statistics data show traffic stops continued to be the most common reason for police-initiated contact across all races, but Black people are stopped at higher rates than others: almost two-thirds (62%) of all Black people whose most recent contact with police in 2022 was police-initiated were the driver in a traffic stop compared to 56-59% among all other groups. Black drivers were also searched or arrested at a rate more than double that of other racial groups: 9% of Black drivers were searched or arrested during traffic stops, compared to 4% of Hispanic drivers, 3% of white drivers, and 5% of drivers of other races. In fact, this represents an increase in the proportion of Black people stopped while driving and subsequently searched or arrested by police: in 2020, less than 6% of Black drivers were searched or arrested during a traffic stop [[link removed]]. As was the case with street stops, these trends serve as further evidence of racist policing during traffic stops. Arrests: Black people were more than twice as likely to be searched or arrested during a traffic stop as white people and Hispanic people. This is consistent with total arrest rates reported by law enforcement, which showed Black people were arrested at a rate (4,544 per 100,000) more than double that of white people (2,155 per 100,000) in 2022.

Police misconduct: Serious racial disparities persisted in the experience of police misconduct. Black people disproportionately experienced police misconduct — defined as the use of slurs, bias, and sexual harassment — in their most recent encounters with police. Four percent of Black people experienced misconduct in their most recent police contact — including those who initiated the contact to report crimes, emergencies, or otherwise seek police help — which is six times the proportion of white people who experienced misconduct (0.7%). Hispanic people also experienced police misconduct in their most recent encounter with police at a significantly higher rate — twice the rate of white people. Threat or use of force: In their most recent police encounters, Black people were over three times as likely as white people to experience the threat or use of force — defined as threat of force, handcuffing, pushing, grabbing, hitting, kicking, using a weapon or other use of nonfatal force (these data do not include people who died from fatal use of force) — and more than twice as likely to experience police shouting or cursing at them. Since 2020, the proportion of white and Hispanic people experiencing the threat or use of force has actually decreased, while the proportion of Black people experiencing threats or nonfatal use of force has increased slightly. In particular, Black people were more likely to be handcuffed, pushed, grabbed, hit, or kicked, or have a weapon used against them by police in 2022 than they were in 2020. And while they accounted for only 12% of people whose most recent contact was police-initiated or traffic accident-related, Black people represented one-third (32%) of all people reporting threatened or nonfatal use of force in their most recent encounter, and one-quarter (24%) of those reporting shouting or cursing by police.

Ultimately, reducing the number of police encounters does mean fewer opportunities for misconduct or use of force, but it has done little to address racism in policing. Black people’s disparate experiences in police encounters that result in searches, arrests, misconduct, or use of force make those encounters more dangerous and deadlier. While information on fatal use of force is not included in this Bureau of Justice Statistics report, we know that Black people are killed by police at a higher rate than other racial groups [[link removed]]. The data in this report provide further evidence of the pervasive pattern of racism throughout the criminal legal system.

Police interactions and use of force are most common among young adults

Young adults aged 18-24 years were the most likely age group to experience any police contact at all (25%), including police-initiated contact (15%), and police contact related to a traffic accident (4%). Young adults were also the most likely age group to experience some kind of law enforcement action — a warning, a ticket, a search or arrest — when their most recent police contact was as a driver during a traffic stop (95%) or in a street stop (28%).

While these rates are concerning, what’s most alarming is the rate of use of force against young adults: more than 1 in 5 people (21%) who experienced the threat or use of force in their most recent police encounter were between 16 and 24 years old. Millions of young adults come into contact with police each year, and the consequences of those interactions are serious and can be life-threatening. Police contact of any kind is not innocuous: over 70% of police killings [[link removed]] in 2023 began with officers responding to a suspected non-violent situation or a case where no crime had been reported, and more than a hundred police killings took place after a traffic stop in 2023. The high rate of police contact among young adults ultimately places them at high risk for dangerous and even fatal consequences.

Disproportionate experiences of use of force among older adults and women

On the other end of the age spectrum, the Bureau of Justice Statistics data reveal a concerning trend among older adults experiencing use of force. While people aged 65 years or older were the least likely adults to experience police contact, they accounted for a growing portion of people experiencing force in police encounters. In 2015, only 0.4% of people who experienced the threat or use of force were 65 or older [[link removed]] and by 2022, the proportion of people experiencing use of force that were 65 or older increased more than tenfold to 5%.

Although women are just as likely to encounter police as men, more and more women are experiencing use of force over time: 28% of people experiencing the threat or use of force by police in 2022 were women, compared to 13% in 1999 [[link removed]]. While the new Bureau of Justice Statistics report did not include statistics on women’s perceptions of police force, the 2020 iteration of the report revealed that women (51%) were more likely than men (44%) to perceive the force they experienced as “excessive.” [[link removed]] Women with any police contact were also somewhat less likely than men to perceive the police as responding promptly and to be satisfied with the police response.

Conclusion

The Police-Public Contact Survey continues to be one of the few opportunities we have to monitor the big picture of police encounters, but it still falls short of revealing how police actually function in our communities. The current survey does not offer information about the motivations behind police-initiated contact, nor does it provide contextual information behind threatened or nonfatal use of force, such as which type of police contact is most frequently associated with force. Without data broken down by sex or gender and race or ethnicity, we have little insight into the impacts police contact has on women of color, trans people, and other demographics not captured by this dataset. Given these limitations, we are often left pulling details from multiple sources to try to piece together some semblance of an understanding of police encounters in the United States. However, even with those restrictions, this Bureau of Justice Statistics report offers a crucial — and rare — opportunity to assess how and why police interactions are happening and whether the outcomes are safe and appropriate for situations actually requiring police intervention at a national level.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes, see the full version of this briefing on our website [[link removed]].

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Not just “a few bad apples”: U.S. police kill civilians at much higher rates than other countries [[link removed]]

It is no secret that police in the U.S. kill civilians at a higher rate than other countries, but just how bad is the problem?

In this 2020 briefing [[link removed]], we crunched the numbers that make clear that police violence is a systemic problem in America, not simply an incidental problem.

Why jails and prisons can’t recruit their way out of the understaffing crisis [[link removed]]

Jails and prisons across the country have record-high vacancies, creating bad working conditions for corrections staff and nightmarish living conditions for incarcerated people.

In this new briefing [[link removed]], we examine why pay raises, benefits, and new facilities haven't turned recruitment around, and what does that tell us about the state of mass incarceration.

34 criminal legal system reforms that can win in 2025 [[link removed]]

We recently released our annual listing of policies that are ripe for victory in the new year [[link removed]]. We provide research on key problems, solutions to them, and examples of where each policy has been implemented.

We also provide tips to push back when lawmakers advocate for failed "tough-on-crime" policies.

It is a vital resource for lawmakers and advocates as they head into their 2025 legislative sessions.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for January 7, 2025 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Despite fewer people experiencing police contact, racial disparities in arrests, police misconduct, and police use of force continue [[link removed]] New Bureau of Justice Statistics data reveal that concerning trends in policing persisted in 2022, even while fewer people interacted with police than in prior years. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra

Almost 50 million people reported contact with police in 2022, reflecting the fewest number of police encounters with the public since 2008 [[link removed]]. But just because the sheer number of police interactions was lower than it has been in decades does not mean the problems with our nation’s fraught system of policing are solved. The newest report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Public-Police Contact series [[link removed]] reveals that racial disparities in police interactions, misconduct, and use of force remained pervasive in 2022. In this briefing, we examine the latest data showing that Black people continued to face higher rates of enforcement actions, police misconduct, and use of force despite relatively similar rates of contact with police. These new data also show heightened levels of police interaction and use of force against young adults, and a growing rate of use of force against women, warranting further investigation of trends in policing.

Millions of people contacted police, but mostly not to report crime

Most police contacts are initiated by residents: almost 30 million people initiated contact with police in 2022. However, only half of these people ever reported possible crimes. More often, they were seeking help. Among people who initiated their most recent contact with police, 25% were reporting a non-crime emergency (like a medical emergency or car accident they weren’t involved in), 26% were reporting other non-emergencies (including requests for custody enforcement or other services, accidental 911 calls, asking for directions, and looking for lost pets), and 3% were block watch-related contacts.

Although we have little national context regarding the reasons for resident-initiated police contact and the outcome of those interactions, a 2022 analysis of over 4 million 911 calls for police service in eight major U.S. cities [[link removed]] found that only 4% of calls were related to violent offenses (including gunshot reports); the majority of calls for service did not result in any action related to law enforcement or crime prevention. In other words, most calls to the police would be best directed elsewhere if communities had the necessary funding and capacity. Given how dangerous seemingly innocent police interactions can be [[link removed]], this is a sign of the need for community investments and government infrastructure that are better suited to address concerns about quality of life (e.g., noise, animals, or disorderly behavior), health (mental, physical, and behavioral), and vehicle and traffic issues — some of the most common themes of 911 calls for service in the 2022 study.

Traffic stops remain the most common reason for police-initiated contact across all demographics

In 2022, fewer than 1 in 5 U.S. residents over the age of 16 (or 18.5%) had face-to-face contact with police, down from 24% [[link removed]] in 2018 [[link removed]]. The Bureau of Justice Statistics attributes this decline to a decrease in the number of traffic stops, which fell by 33% from over 24 million to 16.2 million over this same four-year period. Despite this decline, traffic stops were still the most common type of police-initiated contact, regardless of gender, race, or age: more than 12 million drivers were stopped by police in 2022, and these stops are often fraught with racial bias [[link removed]] and violence [[link removed]].

Racial disparities pervade police encounters

White people were far more likely than Black people, Hispanic people, and Asian people to initiate contact with the police, for reasons including to report possible crimes and emergencies, to participate in block watches, or to seek other kinds of help from police. In fact, 2 out of every 5 (42%) U.S. residents over the age of 16 who had any police contact in 2022 were white people initiating police contact.

On the other hand, people of color — and Black people in particular — were more likely to experience police-initiated contact, including street stops, traffic stops, and arrests. Forty-five percent of Black and Hispanic people who had any contact with the police were approached by police, compared to 40% or less of white people, Asian people, and people of other races. Not only were Black people disproportionately likely to experience traffic stops and arrests, but they were also more likely to experience enforcement actions from police during street stops and traffic stops, and to face police misconduct and use of force:

Street stops: While the survey found little racial or ethnic difference in the likelihood of being stopped on the street by police, Black people were somewhat more likely to face enforcement actions from police in street stops: 18% of Black people stopped received a warning compared to 15% of white people, and 8% of Black people stopped were searched or arrested compared to 6% of white people. Hispanic people were far less likely (11%) to receive an enforcement action when stopped than white (24%) or Black people (25%).

Traffic stops: Traffic stops are a common site of police violence: according to the 2023 Police Violence Report from Mapping Police Violence, more than 100 police killings (13%) occurred at traffic stops [[link removed]] in 2023. The new Bureau of Justice Statistics data show traffic stops continued to be the most common reason for police-initiated contact across all races, but Black people are stopped at higher rates than others: almost two-thirds (62%) of all Black people whose most recent contact with police in 2022 was police-initiated were the driver in a traffic stop compared to 56-59% among all other groups. Black drivers were also searched or arrested at a rate more than double that of other racial groups: 9% of Black drivers were searched or arrested during traffic stops, compared to 4% of Hispanic drivers, 3% of white drivers, and 5% of drivers of other races. In fact, this represents an increase in the proportion of Black people stopped while driving and subsequently searched or arrested by police: in 2020, less than 6% of Black drivers were searched or arrested during a traffic stop [[link removed]]. As was the case with street stops, these trends serve as further evidence of racist policing during traffic stops. Arrests: Black people were more than twice as likely to be searched or arrested during a traffic stop as white people and Hispanic people. This is consistent with total arrest rates reported by law enforcement, which showed Black people were arrested at a rate (4,544 per 100,000) more than double that of white people (2,155 per 100,000) in 2022.

Police misconduct: Serious racial disparities persisted in the experience of police misconduct. Black people disproportionately experienced police misconduct — defined as the use of slurs, bias, and sexual harassment — in their most recent encounters with police. Four percent of Black people experienced misconduct in their most recent police contact — including those who initiated the contact to report crimes, emergencies, or otherwise seek police help — which is six times the proportion of white people who experienced misconduct (0.7%). Hispanic people also experienced police misconduct in their most recent encounter with police at a significantly higher rate — twice the rate of white people. Threat or use of force: In their most recent police encounters, Black people were over three times as likely as white people to experience the threat or use of force — defined as threat of force, handcuffing, pushing, grabbing, hitting, kicking, using a weapon or other use of nonfatal force (these data do not include people who died from fatal use of force) — and more than twice as likely to experience police shouting or cursing at them. Since 2020, the proportion of white and Hispanic people experiencing the threat or use of force has actually decreased, while the proportion of Black people experiencing threats or nonfatal use of force has increased slightly. In particular, Black people were more likely to be handcuffed, pushed, grabbed, hit, or kicked, or have a weapon used against them by police in 2022 than they were in 2020. And while they accounted for only 12% of people whose most recent contact was police-initiated or traffic accident-related, Black people represented one-third (32%) of all people reporting threatened or nonfatal use of force in their most recent encounter, and one-quarter (24%) of those reporting shouting or cursing by police.

Ultimately, reducing the number of police encounters does mean fewer opportunities for misconduct or use of force, but it has done little to address racism in policing. Black people’s disparate experiences in police encounters that result in searches, arrests, misconduct, or use of force make those encounters more dangerous and deadlier. While information on fatal use of force is not included in this Bureau of Justice Statistics report, we know that Black people are killed by police at a higher rate than other racial groups [[link removed]]. The data in this report provide further evidence of the pervasive pattern of racism throughout the criminal legal system.

Police interactions and use of force are most common among young adults

Young adults aged 18-24 years were the most likely age group to experience any police contact at all (25%), including police-initiated contact (15%), and police contact related to a traffic accident (4%). Young adults were also the most likely age group to experience some kind of law enforcement action — a warning, a ticket, a search or arrest — when their most recent police contact was as a driver during a traffic stop (95%) or in a street stop (28%).

While these rates are concerning, what’s most alarming is the rate of use of force against young adults: more than 1 in 5 people (21%) who experienced the threat or use of force in their most recent police encounter were between 16 and 24 years old. Millions of young adults come into contact with police each year, and the consequences of those interactions are serious and can be life-threatening. Police contact of any kind is not innocuous: over 70% of police killings [[link removed]] in 2023 began with officers responding to a suspected non-violent situation or a case where no crime had been reported, and more than a hundred police killings took place after a traffic stop in 2023. The high rate of police contact among young adults ultimately places them at high risk for dangerous and even fatal consequences.

Disproportionate experiences of use of force among older adults and women

On the other end of the age spectrum, the Bureau of Justice Statistics data reveal a concerning trend among older adults experiencing use of force. While people aged 65 years or older were the least likely adults to experience police contact, they accounted for a growing portion of people experiencing force in police encounters. In 2015, only 0.4% of people who experienced the threat or use of force were 65 or older [[link removed]] and by 2022, the proportion of people experiencing use of force that were 65 or older increased more than tenfold to 5%.

Although women are just as likely to encounter police as men, more and more women are experiencing use of force over time: 28% of people experiencing the threat or use of force by police in 2022 were women, compared to 13% in 1999 [[link removed]]. While the new Bureau of Justice Statistics report did not include statistics on women’s perceptions of police force, the 2020 iteration of the report revealed that women (51%) were more likely than men (44%) to perceive the force they experienced as “excessive.” [[link removed]] Women with any police contact were also somewhat less likely than men to perceive the police as responding promptly and to be satisfied with the police response.

Conclusion

The Police-Public Contact Survey continues to be one of the few opportunities we have to monitor the big picture of police encounters, but it still falls short of revealing how police actually function in our communities. The current survey does not offer information about the motivations behind police-initiated contact, nor does it provide contextual information behind threatened or nonfatal use of force, such as which type of police contact is most frequently associated with force. Without data broken down by sex or gender and race or ethnicity, we have little insight into the impacts police contact has on women of color, trans people, and other demographics not captured by this dataset. Given these limitations, we are often left pulling details from multiple sources to try to piece together some semblance of an understanding of police encounters in the United States. However, even with those restrictions, this Bureau of Justice Statistics report offers a crucial — and rare — opportunity to assess how and why police interactions are happening and whether the outcomes are safe and appropriate for situations actually requiring police intervention at a national level.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes, see the full version of this briefing on our website [[link removed]].

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Not just “a few bad apples”: U.S. police kill civilians at much higher rates than other countries [[link removed]]

It is no secret that police in the U.S. kill civilians at a higher rate than other countries, but just how bad is the problem?

In this 2020 briefing [[link removed]], we crunched the numbers that make clear that police violence is a systemic problem in America, not simply an incidental problem.

Why jails and prisons can’t recruit their way out of the understaffing crisis [[link removed]]

Jails and prisons across the country have record-high vacancies, creating bad working conditions for corrections staff and nightmarish living conditions for incarcerated people.

In this new briefing [[link removed]], we examine why pay raises, benefits, and new facilities haven't turned recruitment around, and what does that tell us about the state of mass incarceration.

34 criminal legal system reforms that can win in 2025 [[link removed]]

We recently released our annual listing of policies that are ripe for victory in the new year [[link removed]]. We provide research on key problems, solutions to them, and examples of where each policy has been implemented.

We also provide tips to push back when lawmakers advocate for failed "tough-on-crime" policies.

It is a vital resource for lawmakers and advocates as they head into their 2025 legislative sessions.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor