Email

Happy Hanukkah! Let's talk about Jews

| From | Ben Samuels <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Happy Hanukkah! Let's talk about Jews |

| Date | December 30, 2024 1:07 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

I’m Jewish. That’s not a surprise to the people who know me, and it’s something I talked about publicly [ [link removed] ] when I ran for Congress.

In large part because of what’s happening in the Middle East, Jewish issues were more top of mind during the 2024 presidential election than in the past. But that’s been analyzed every which way already, and it’s not what I’ll focus on here.

Instead, I’ll talk about where Jews live, and how the 100+ million Americans who don’t know someone Jewish think about these issues—Americans like Carter, who I interviewed for this newsletter. He’s an Army Reserve veteran, and until we met, he hadn’t ever met a Jewish person before.

Going into our conversation, my sense had been that Jews are either loved or loathed in the U.S.:

Jewish people are the most favorably viewed religious group in the U.S. [ [link removed] ]

Simultaneously, and paradoxically, Jews are also widely distrusted [ [link removed] ] and are, by far, the target of the most religious hate crimes [ [link removed] ] of any group in America.

But the truth is more nuanced: there are lots of people who don’t think about these issues at all, because they’re not relevant in their communities.

As we do more cultural exchange across religious and cultural groups within America—work I believe is vital—it’s important to keep that in mind.

Jewish Geography [ [link removed] ]

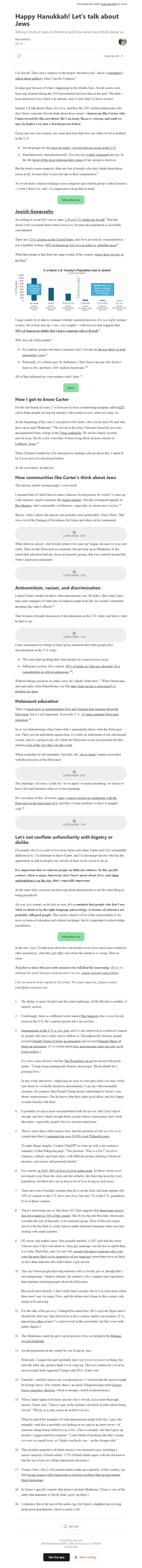

According to recent Pew survey data, 2.4% of U.S. adults are Jewish [ [link removed] ]. But that doesn’t tell you much about where Jews live, because the population is incredibly concentrated.

There are 3,143 counties in the United States [ [link removed] ], and Jews are heavily concentrated in just a handful of them: 96% of American Jews live in urban or suburban areas [ [link removed] ].

What that means is that there are large swaths of the country where there are few or no Jews [ [link removed] ]:

Using county-level data to estimate whether someone knows a Jew is a highly inexact science, but it does line up—very, very roughly—with surveys that suggests that 34% of American adults don’t know someone who is Jewish [ [link removed] ].

Why does all of this matter?

For starters, people who know someone who’s Jewish are far less likely to hold antisemitic views [ [link removed] ].

Personally, it’s a blind spot: by definition, I don’t know anyone who doesn’t know a Jew, and that’s 100+ million Americans.

All of that informed my conversation with Carter.

How I got to know Carter

For the last bunch of years, I’ve been involved in a mentorship program called ACP [ [link removed] ], which helps people leaving the military with resume review, interview prep, etc.

At the beginning of the year, I was paired with Carter, who’s in his mid-20s and who grew up in rural Oklahoma. He served in the Army National Guard for six years and graduated from college in the Texas panhandle [ [link removed] ]. He and his family recently moved away, but for a few years they’d been living about an hour outside of Lubbock, Texas [ [link removed] ].

When I floated whether he’d be interested in chatting with me about this, I asked if he’d ever met a Jewish person before.

As far as he knew, he had not.

How communities like Carter’s think about Jews

The answer, maybe unsurprisingly, is not much.

I assumed that if I asked him to name a famous Jewish person, he would’ve come up with someone: maybe someone like Adam Sandler [ [link removed] ], who has widespread appeal, or Ben Shapiro [ [link removed] ], who’s reasonably well known—especially in conservative circles.

But no, when I asked, the answer was probably more predictable: Jesus Christ. That was a lot of the framing of Jewishness for Carter and others in his community.

What about in school—did Jewish culture ever come up? Again, the answer is no, not really. More on the Holocaust in a moment, but growing up in Oklahoma, to the extent that education had any focus on minority groups, that was centered around the Native American community.

Antisemitism, racism, and discrimination

I asked Carter whether he knew what antisemitism was. He didn’t. But when I gave him some examples of what anti-Jewishness might look like, he couldn’t remember anything like what I offered.

That became a broader discussion of discrimination in the U.S. today, and here’s what he had to say:

Carter mentioned two things to back up his assertion that white people face discrimination in the U.S. today:

The sense that anything that white people do is perceived as racist.

Affirmative action. (For context: 68% of adults say that race shouldn’t be a consideration in college admissions [ [link removed] ].)

Without taking a position on either issue, he’s hardly alone here. White Americans, and especially white Republicans, say that anti-white racism is increasingly a problem for them [ [link removed] ].

Holocaust education

There is much more to understanding Jews and Judaism than learning about the Holocaust [ [link removed] ], but it’s still important. Across the U.S., 23 states mandate Holocaust education [ [link removed] ].

So it was disheartening when Carter didn’t immediately know what the Holocaust was. That’s not an indictment against him; it’s really an indictment of our educational system. And it’s jarring to me, for whom the Holocaust is not just personal but also informs a lot of the way that I see the world [ [link removed] ].

When reminded, he did remember, basically, the “never again” [ [link removed] ] mantra associated with the atrocities of the Holocaust.

The challenge, of course, is that for “never again” to mean something, we’d have to know first and foremost what we’re not repeating.

He’s not alone in this, of course; many younger people are unfamiliar with the Holocaust or the particulars of it [ [link removed] ], and that’s a huge problem we have to grapple with.

Let’s not conflate unfamiliarity with bigotry or dislike

For people who live a state or two away from each other, Carter and I live remarkably different lives. I’m fortunate to know Carter, and I’d encourage anyone who has the opportunity to talk to people way outside of their social circles to do so.

It is important that we educate people on different cultures. In this specific context, when so many Americans don’t know much about Jews, and when antisemitism is on the rise [ [link removed] ], that’s especially important.

At the same time, someone not knowing about antisemitism is not the same thing as being prejudiced.

As ever, in a country as divided as ours, it’s a reminder that people who don’t use what we deem to be the right language, phraseology, or frames of reference are probably still good people. That doesn’t absolve of us of the responsibility to do more in terms of education and cultural exchange, but it’s important to acknowledge nonetheless.

In the new year, I’ll talk more about how the media covers Jews (and issues related to other minorities), what they get right, and where the narrative is wrong. More to come.

Feel free to share this post with someone who will find this interesting. (If you’re reading this email because someone sent it to you, please consider subscribing [ [link removed] ].)

I do not receive direct replies to this email. For press inquiries, please contact [email protected].

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

I’m Jewish. That’s not a surprise to the people who know me, and it’s something I talked about publicly [ [link removed] ] when I ran for Congress.

In large part because of what’s happening in the Middle East, Jewish issues were more top of mind during the 2024 presidential election than in the past. But that’s been analyzed every which way already, and it’s not what I’ll focus on here.

Instead, I’ll talk about where Jews live, and how the 100+ million Americans who don’t know someone Jewish think about these issues—Americans like Carter, who I interviewed for this newsletter. He’s an Army Reserve veteran, and until we met, he hadn’t ever met a Jewish person before.

Going into our conversation, my sense had been that Jews are either loved or loathed in the U.S.:

Jewish people are the most favorably viewed religious group in the U.S. [ [link removed] ]

Simultaneously, and paradoxically, Jews are also widely distrusted [ [link removed] ] and are, by far, the target of the most religious hate crimes [ [link removed] ] of any group in America.

But the truth is more nuanced: there are lots of people who don’t think about these issues at all, because they’re not relevant in their communities.

As we do more cultural exchange across religious and cultural groups within America—work I believe is vital—it’s important to keep that in mind.

Jewish Geography [ [link removed] ]

According to recent Pew survey data, 2.4% of U.S. adults are Jewish [ [link removed] ]. But that doesn’t tell you much about where Jews live, because the population is incredibly concentrated.

There are 3,143 counties in the United States [ [link removed] ], and Jews are heavily concentrated in just a handful of them: 96% of American Jews live in urban or suburban areas [ [link removed] ].

What that means is that there are large swaths of the country where there are few or no Jews [ [link removed] ]:

Using county-level data to estimate whether someone knows a Jew is a highly inexact science, but it does line up—very, very roughly—with surveys that suggests that 34% of American adults don’t know someone who is Jewish [ [link removed] ].

Why does all of this matter?

For starters, people who know someone who’s Jewish are far less likely to hold antisemitic views [ [link removed] ].

Personally, it’s a blind spot: by definition, I don’t know anyone who doesn’t know a Jew, and that’s 100+ million Americans.

All of that informed my conversation with Carter.

How I got to know Carter

For the last bunch of years, I’ve been involved in a mentorship program called ACP [ [link removed] ], which helps people leaving the military with resume review, interview prep, etc.

At the beginning of the year, I was paired with Carter, who’s in his mid-20s and who grew up in rural Oklahoma. He served in the Army National Guard for six years and graduated from college in the Texas panhandle [ [link removed] ]. He and his family recently moved away, but for a few years they’d been living about an hour outside of Lubbock, Texas [ [link removed] ].

When I floated whether he’d be interested in chatting with me about this, I asked if he’d ever met a Jewish person before.

As far as he knew, he had not.

How communities like Carter’s think about Jews

The answer, maybe unsurprisingly, is not much.

I assumed that if I asked him to name a famous Jewish person, he would’ve come up with someone: maybe someone like Adam Sandler [ [link removed] ], who has widespread appeal, or Ben Shapiro [ [link removed] ], who’s reasonably well known—especially in conservative circles.

But no, when I asked, the answer was probably more predictable: Jesus Christ. That was a lot of the framing of Jewishness for Carter and others in his community.

What about in school—did Jewish culture ever come up? Again, the answer is no, not really. More on the Holocaust in a moment, but growing up in Oklahoma, to the extent that education had any focus on minority groups, that was centered around the Native American community.

Antisemitism, racism, and discrimination

I asked Carter whether he knew what antisemitism was. He didn’t. But when I gave him some examples of what anti-Jewishness might look like, he couldn’t remember anything like what I offered.

That became a broader discussion of discrimination in the U.S. today, and here’s what he had to say:

Carter mentioned two things to back up his assertion that white people face discrimination in the U.S. today:

The sense that anything that white people do is perceived as racist.

Affirmative action. (For context: 68% of adults say that race shouldn’t be a consideration in college admissions [ [link removed] ].)

Without taking a position on either issue, he’s hardly alone here. White Americans, and especially white Republicans, say that anti-white racism is increasingly a problem for them [ [link removed] ].

Holocaust education

There is much more to understanding Jews and Judaism than learning about the Holocaust [ [link removed] ], but it’s still important. Across the U.S., 23 states mandate Holocaust education [ [link removed] ].

So it was disheartening when Carter didn’t immediately know what the Holocaust was. That’s not an indictment against him; it’s really an indictment of our educational system. And it’s jarring to me, for whom the Holocaust is not just personal but also informs a lot of the way that I see the world [ [link removed] ].

When reminded, he did remember, basically, the “never again” [ [link removed] ] mantra associated with the atrocities of the Holocaust.

The challenge, of course, is that for “never again” to mean something, we’d have to know first and foremost what we’re not repeating.

He’s not alone in this, of course; many younger people are unfamiliar with the Holocaust or the particulars of it [ [link removed] ], and that’s a huge problem we have to grapple with.

Let’s not conflate unfamiliarity with bigotry or dislike

For people who live a state or two away from each other, Carter and I live remarkably different lives. I’m fortunate to know Carter, and I’d encourage anyone who has the opportunity to talk to people way outside of their social circles to do so.

It is important that we educate people on different cultures. In this specific context, when so many Americans don’t know much about Jews, and when antisemitism is on the rise [ [link removed] ], that’s especially important.

At the same time, someone not knowing about antisemitism is not the same thing as being prejudiced.

As ever, in a country as divided as ours, it’s a reminder that people who don’t use what we deem to be the right language, phraseology, or frames of reference are probably still good people. That doesn’t absolve of us of the responsibility to do more in terms of education and cultural exchange, but it’s important to acknowledge nonetheless.

In the new year, I’ll talk more about how the media covers Jews (and issues related to other minorities), what they get right, and where the narrative is wrong. More to come.

Feel free to share this post with someone who will find this interesting. (If you’re reading this email because someone sent it to you, please consider subscribing [ [link removed] ].)

I do not receive direct replies to this email. For press inquiries, please contact [email protected].

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a