Email

The vanishing voices of WWII veterans

| From | Ben Samuels <[email protected]> |

| Subject | The vanishing voices of WWII veterans |

| Date | December 3, 2024 4:09 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

When I was in fifth grade, after a unit on U.S. history, Mr. Greco gave us an assignment: interview a World War II veteran, and report back to the class with what we’d learned.

This was in 2002. Back then, that wasn’t particularly challenging: a lot of us had grandfathers who fought in WWII [ [link removed] ], and people who didn’t surely had a neighbor or a family friend who did. Most veterans were in their 70s or 80s.

Today, of course, is a different story. The youngest WWII veterans are 97.

It feels like every few weeks, you read a new story about a “last surviving” WWII veteran: the last of the Band of Brothers [ [link removed] ] or the last Doolittle Raider [ [link removed] ] or the last USS [ [link removed] ]Arizona [ [link removed] ] survivor [ [link removed] ], for instance. Within the next decade or so, the final World War II veteran will have died.

We are fast losing our tether to the people who fought to protect the world from fascism and tyranny. We’re losing the people who understand the dangers of isolationism, and why international collaboration is good.

Understanding that maybe helps us do something about it.

World War II veterans were ubiquitous for generations

Until recently, this wasn’t an issue.

16.4 million Americans [ [link removed] ] served during WWII, about 12% of the country’s population at the time [ [link removed] ]—an astonishingly high number. And that still understates the impact that WWII veterans would have for decades to come.

For generations, they were present in all walks of life—at our businesses, in our communities, and at our schools. They were also very present in American politics.

WWII veterans in elected office

Even against the baseline of enormous participation in World War II, veterans were disproportionately well represented in politics for decades.

From 1953 to 1993, every single President of the United States was a WWII veteran. And at its peak in the late ’60s and early ’70s, 54% of U.S. Senators had served in WWII [ [link removed] ].

Even 40 years after that peak, there were still Senators who’d served in the War, building seniority and expertise and cache such that even as their number dwindled, they continued to have an outsized impact on legislating and public discourse.

Why talk about this now?

The Greatest Generation [ [link removed] ] is valorized, at times in ways that sweep under the rug the challenges of wartime and post-War America. Rising prosperity in the late ’40s and ’50s often excluded both women and minorities, for instance, despite their contributions to the war effort.

The goal here is not to deify World War II veterans. Rather, it’s important to acknowledge that a group of people came together to win a war whose set of goals (non-exhaustively) included:

Defeating tyranny.

Fighting for the rights of minorities and the discriminated against.

Fighting for self-determination and democracy.

It’s no surprise, then, that in Congress, support for NATO, for international trade, and for the rights of refugees had been strong for decades.

That’s obviously quite different now. Donald Trump is threatening to cut ties to NATO [ [link removed] ], blow up international trade [ [link removed] ], and block refugees from coming [ [link removed] ] to the United States.

A generation ago, lawmakers would’ve (rightly) seen all of this as a threat to world peace and stability. They’d seen and experienced what happens when you dive head-first into isolationism.

But those people are mostly gone. Without their collective memory, wisdom, and experience, we are squarely living in the post-post-War era.

Younger people don’t believe in a lot of what America has stood for since 1945

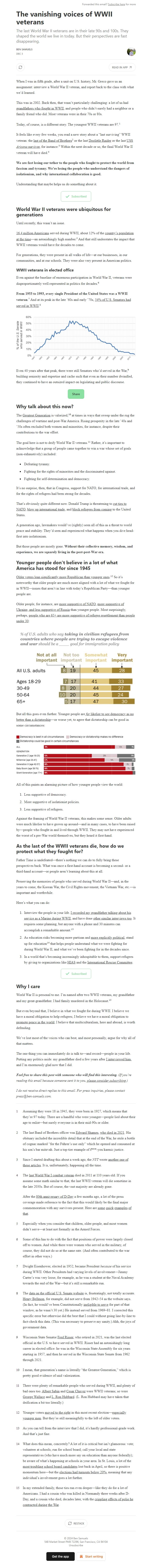

Older voters lean significantly more Republican than younger ones [ [link removed] ]. So it’s noteworthy that older people are much more aligned with a lot of what we fought for in WWII—issues that aren’t in line with today’s Republican Party—than younger people are.

Older people, for instance, are more supportive of NATO [ [link removed] ], more supportive of Ukraine, and less supportive of Russia [ [link removed] ] than younger people. Most surprisingly, perhaps, people who are 65+ are more supportive of refugee resettlement than people under 30 [ [link removed] ]:

But all this goes even further. Younger people are far [ [link removed] ] likelier to see democracy as no better than a dictatorship [ [link removed] ]—or worse yet, to agree that dictatorship can be good in some circumstances:

All of this paints an alarming picture of how younger people view the world:

Less supportive of democracy.

More supportive of isolationist policies.

Less supportive of refugees.

Against the framing of World War II veterans, this makes some sense. Older adults were much likelier to have grown up around—and in many cases, to have been raised by—people who fought in and lived through WWII. They may not have experienced the worst of a pre-War world themselves, but they heard it first-hand.

As the last of the WWII veterans die, how do we protect what they fought for?

Father Time is undefeated—there’s nothing we can do to fully bring these perspectives back. What was once a first-hand account is becoming a second- or a third-hand account—or people aren’t learning about this at all.

Preserving the memories of people who served during World War II—and, in the years to come, the Korean War, the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War, etc.—is important and worthwhile.

Here’s what you can do:

Interview the people in your life. I recorded my grandfather talking about his service as a Marine during WWII [ [link removed] ], and have done other similar interviews too [ [link removed] ]. It requires some planning, but anyone with a phone and 30 minutes can accomplish a remarkable amount.

As education risks becoming more partisan and more explicitly political [ [link removed] ], stand up for education that helps people understand what we were fighting for during World War II, and what we’ve been fighting for in the decades since.

In a world that’s becoming increasingly inhospitable to them, support refugees by giving to organizations like HIAS [ [link removed] ] and the International Rescue Committee [ [link removed] ].

Why I care

World War II is personal to me. I’m named after two WWII veterans, my grandfather and my great-grandfather. I had family murdered in the Holocaust.

But even beyond that, I believe in what we fought for during WWII. I believe we have a moral obligation to help refugees; I believe we have a moral obligation to promote peace in the world [ [link removed] ]; I believe that multiculturalism, here and abroad, is worth defending.

We’ve lost most of the voices who can best, and most personally, argue for why all of that matters.

The one thing you can immediately do is talk to—and record—people in your life. Putting any politics aside: my grandfather died a few years after I interviewed him [ [link removed] ], and I’m enormously glad now that I did.

Feel free to share this post with someone who will find this interesting. (If you’re reading this email because someone sent it to you, please consider subscribing [ [link removed] ].)

I do not receive direct replies to this email. For press inquiries, please contact [email protected].

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

When I was in fifth grade, after a unit on U.S. history, Mr. Greco gave us an assignment: interview a World War II veteran, and report back to the class with what we’d learned.

This was in 2002. Back then, that wasn’t particularly challenging: a lot of us had grandfathers who fought in WWII [ [link removed] ], and people who didn’t surely had a neighbor or a family friend who did. Most veterans were in their 70s or 80s.

Today, of course, is a different story. The youngest WWII veterans are 97.

It feels like every few weeks, you read a new story about a “last surviving” WWII veteran: the last of the Band of Brothers [ [link removed] ] or the last Doolittle Raider [ [link removed] ] or the last USS [ [link removed] ]Arizona [ [link removed] ] survivor [ [link removed] ], for instance. Within the next decade or so, the final World War II veteran will have died.

We are fast losing our tether to the people who fought to protect the world from fascism and tyranny. We’re losing the people who understand the dangers of isolationism, and why international collaboration is good.

Understanding that maybe helps us do something about it.

World War II veterans were ubiquitous for generations

Until recently, this wasn’t an issue.

16.4 million Americans [ [link removed] ] served during WWII, about 12% of the country’s population at the time [ [link removed] ]—an astonishingly high number. And that still understates the impact that WWII veterans would have for decades to come.

For generations, they were present in all walks of life—at our businesses, in our communities, and at our schools. They were also very present in American politics.

WWII veterans in elected office

Even against the baseline of enormous participation in World War II, veterans were disproportionately well represented in politics for decades.

From 1953 to 1993, every single President of the United States was a WWII veteran. And at its peak in the late ’60s and early ’70s, 54% of U.S. Senators had served in WWII [ [link removed] ].

Even 40 years after that peak, there were still Senators who’d served in the War, building seniority and expertise and cache such that even as their number dwindled, they continued to have an outsized impact on legislating and public discourse.

Why talk about this now?

The Greatest Generation [ [link removed] ] is valorized, at times in ways that sweep under the rug the challenges of wartime and post-War America. Rising prosperity in the late ’40s and ’50s often excluded both women and minorities, for instance, despite their contributions to the war effort.

The goal here is not to deify World War II veterans. Rather, it’s important to acknowledge that a group of people came together to win a war whose set of goals (non-exhaustively) included:

Defeating tyranny.

Fighting for the rights of minorities and the discriminated against.

Fighting for self-determination and democracy.

It’s no surprise, then, that in Congress, support for NATO, for international trade, and for the rights of refugees had been strong for decades.

That’s obviously quite different now. Donald Trump is threatening to cut ties to NATO [ [link removed] ], blow up international trade [ [link removed] ], and block refugees from coming [ [link removed] ] to the United States.

A generation ago, lawmakers would’ve (rightly) seen all of this as a threat to world peace and stability. They’d seen and experienced what happens when you dive head-first into isolationism.

But those people are mostly gone. Without their collective memory, wisdom, and experience, we are squarely living in the post-post-War era.

Younger people don’t believe in a lot of what America has stood for since 1945

Older voters lean significantly more Republican than younger ones [ [link removed] ]. So it’s noteworthy that older people are much more aligned with a lot of what we fought for in WWII—issues that aren’t in line with today’s Republican Party—than younger people are.

Older people, for instance, are more supportive of NATO [ [link removed] ], more supportive of Ukraine, and less supportive of Russia [ [link removed] ] than younger people. Most surprisingly, perhaps, people who are 65+ are more supportive of refugee resettlement than people under 30 [ [link removed] ]:

But all this goes even further. Younger people are far [ [link removed] ] likelier to see democracy as no better than a dictatorship [ [link removed] ]—or worse yet, to agree that dictatorship can be good in some circumstances:

All of this paints an alarming picture of how younger people view the world:

Less supportive of democracy.

More supportive of isolationist policies.

Less supportive of refugees.

Against the framing of World War II veterans, this makes some sense. Older adults were much likelier to have grown up around—and in many cases, to have been raised by—people who fought in and lived through WWII. They may not have experienced the worst of a pre-War world themselves, but they heard it first-hand.

As the last of the WWII veterans die, how do we protect what they fought for?

Father Time is undefeated—there’s nothing we can do to fully bring these perspectives back. What was once a first-hand account is becoming a second- or a third-hand account—or people aren’t learning about this at all.

Preserving the memories of people who served during World War II—and, in the years to come, the Korean War, the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War, etc.—is important and worthwhile.

Here’s what you can do:

Interview the people in your life. I recorded my grandfather talking about his service as a Marine during WWII [ [link removed] ], and have done other similar interviews too [ [link removed] ]. It requires some planning, but anyone with a phone and 30 minutes can accomplish a remarkable amount.

As education risks becoming more partisan and more explicitly political [ [link removed] ], stand up for education that helps people understand what we were fighting for during World War II, and what we’ve been fighting for in the decades since.

In a world that’s becoming increasingly inhospitable to them, support refugees by giving to organizations like HIAS [ [link removed] ] and the International Rescue Committee [ [link removed] ].

Why I care

World War II is personal to me. I’m named after two WWII veterans, my grandfather and my great-grandfather. I had family murdered in the Holocaust.

But even beyond that, I believe in what we fought for during WWII. I believe we have a moral obligation to help refugees; I believe we have a moral obligation to promote peace in the world [ [link removed] ]; I believe that multiculturalism, here and abroad, is worth defending.

We’ve lost most of the voices who can best, and most personally, argue for why all of that matters.

The one thing you can immediately do is talk to—and record—people in your life. Putting any politics aside: my grandfather died a few years after I interviewed him [ [link removed] ], and I’m enormously glad now that I did.

Feel free to share this post with someone who will find this interesting. (If you’re reading this email because someone sent it to you, please consider subscribing [ [link removed] ].)

I do not receive direct replies to this email. For press inquiries, please contact [email protected].

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a