| From | Brad Sears <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Saying goodbye to Stu Walter |

| Date | November 19, 2024 6:26 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

([link removed])

A message from Brad Sears, Founding Executive Director

Dear friends,

It is with much sadness that I must let you know that Stu Walter, one of the founders of the Williams Institute, has passed away.

Stu was a quiet man of uncommon intelligence, generosity, strength, and warmth. His sharp eyes did not miss anything. His expansive heart accepted everyone.

Above everything, Stu was a warrior. Faced with Herculean challenges, he was dedicated to finding solutions not only for himself but for his broader communities. At various points in his life, that meant pushing back against a pre-Stonewall America that simply did not want gay men to exist, living openly in a same-sex couple decades before marriage equality, fighting for his own life and that of his community during the darkest days of AIDS, and ultimately making sure the Williams Institute was focused on those who needed the most support--including transgender people, LGBTQ people of color, and those living in poverty.

Born in 1943, the son of an elementary school principal and a cemetery superintendent, Stu started life as a gifted scientist and musician. In elementary school, Stu won science fair honors for building an electronic well, radio transmitter, electrocardiograph, and a five-foot robot that could "talk, swing its arms, and clutch things." He became a talented violinist in high school, playing in the Pennsylvania State Regional Orchestra. When he enrolled in the University of Miami in 1961, he declared a major in Physics and a minor in Math. He wrote of his plans to attend graduate school to become a nuclear physicist. In addition to the violin, he listed the piano, alto horn, and "building boats" as hobbies.

The crucible of homophobia of the 1950s and 60s meant the world never got to know the contributions of Stu, the scientist and musician. But he forged a path of service, nonetheless. He left the University of Miami and spent several years moving between the growing LGBTQ communities of New York City, San Francisco, and finally, Los Angeles, where he met Chuck Williams in 1967.

Stu talked about the risks of being gay at the time, including being attacked, entrapped by the police, and fired from a job. He spoke about California's Atascadero State Hospital, notorious in the United States as one of the worst facilities that would confine gay men and youth as "sexual deviants" for conversion therapy for indefinite periods of time. But he rode through those years on a motorcycle, frequently in red speedos on the way to some of the first LGBTQ restaurants in San Francisco.

In the 1980s, Stu was diagnosed with HIV and then AIDS. He tried a number of toxic medications and alternative therapies that would seem bizarre to anyone but the dying and desperate before more effective medications became available in the mid-1990s. Stu knew if those medications had become available even a year later, he would not have survived. But Stu did survive, beating the odds not only against AIDS but lung cancer and COPD, living a full life of over eight decades.

Stu did not take this borrowed time for granted. When the world dictated a life of loneliness, Stu created community. When the world punched down with homophobia, he helped forge a path forward not just for himself but for all LGBTQ people.

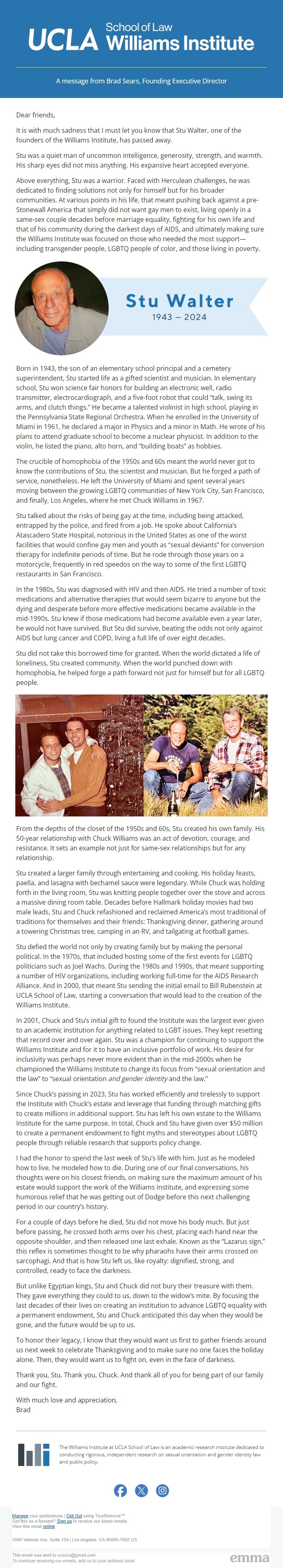

From the depths of the closet of the 1950s and 60s, Stu created his own family. His 50-year relationship with Chuck Williams was an act of devotion, courage, and resistance. It sets an example not just for same-sex relationships but for any relationship.

Stu created a larger family through entertaining and cooking. His holiday feasts, paella, and lasagna with bechamel sauce were legendary. While Chuck was holding forth in the living room, Stu was knitting people together over the stove and across a massive dining room table. Decades before Hallmark holiday movies had two male leads, Stu and Chuck refashioned and reclaimed America's most traditional of traditions for themselves and their friends: Thanksgiving dinner, gathering around a towering Christmas tree, camping in an RV, and tailgating at football games.

Stu defied the world not only by creating family but by making the personal political. In the 1970s, that included hosting some of the first events for LGBTQ politicians such as Joel Wachs. During the 1980s and 1990s, that meant supporting a number of HIV organizations, including working full-time for the AIDS Research Alliance. And in 2000, that meant Stu sending the initial email to Bill Rubenstein at UCLA School of Law, starting a conversation that would lead to the creation of the Williams Institute.

In 2001, Chuck and Stu's initial gift to found the Institute was the largest ever given to an academic institution for anything related to LGBT issues. They kept resetting that record over and over again. Stu was a champion for continuing to support the Williams Institute and for it to have an inclusive portfolio of work. His desire for inclusivity was perhaps never more evident than in the mid-2000s when he championed the Williams Institute to change its focus from "sexual orientation and the law" to "sexual orientation and gender identity and the law."

Since Chuck's passing in 2023, Stu has worked efficiently and tirelessly to support the Institute with Chuck's estate and leverage that funding through matching gifts to create millions in additional support. Stu has left his own estate to the Williams Institute for the same purpose. In total, Chuck and Stu have given over $50 million to create a permanent endowment to fight myths and stereotypes about LGBTQ people through reliable research that supports policy change.

I had the honor to spend the last week of Stu's life with him. Just as he modeled how to live, he modeled how to die. During one of our final conversations, his thoughts were on his closest friends, on making sure the maximum amount of his estate would support the work of the Williams Institute, and expressing some humorous relief that he was getting out of Dodge before this next challenging period in our country's history.

For a couple of days before he died, Stu did not move his body much. But just before passing, he crossed both arms over his chest, placing each hand near the opposite shoulder, and then released one last exhale. Known as the "Lazarus sign," this reflex is sometimes thought to be why pharaohs have their arms crossed on sarcophagi. And that is how Stu left us, like royalty: dignified, strong, and controlled, ready to face the darkness.

But unlike Egyptian kings, Stu and Chuck did not bury their treasure with them. They gave everything they could to us, down to the widow's mite. By focusing the last decades of their lives on creating an institution to advance LGBTQ equality with a permanent endowment, Stu and Chuck anticipated this day when they would be gone, and the future would be up to us.

To honor their legacy, I know that they would want us first to gather friends around us next week to celebrate Thanksgiving and to make sure no one faces the holiday alone. Then, they would want us to fight on, even in the face of darkness.

Thank you, Stu. Thank you, Chuck. And thank all of you for being part of our family and our fight.

With much love and appreciation,

Brad

The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law is an academic research institute dedicated to conducting rigorous, independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy.

([link removed])

% link:[link removed] name="[link removed]" content="" %]

% link:[link removed] name="[link removed]" content="" %]

[Manage]([link removed]) your preferences | [Opt Out]([link removed]) using TrueRemove™

Got this as a forward? [Sign up]([link removed]) to receive our future emails.

View this email [online]([link removed]).

1060 Veteran Ave. Suite 134 | Los Angeles, CA 90095-7092 US

This email was sent to [email protected].

To continue receiving our emails, add us to your address book.

([link removed])

A message from Brad Sears, Founding Executive Director

Dear friends,

It is with much sadness that I must let you know that Stu Walter, one of the founders of the Williams Institute, has passed away.

Stu was a quiet man of uncommon intelligence, generosity, strength, and warmth. His sharp eyes did not miss anything. His expansive heart accepted everyone.

Above everything, Stu was a warrior. Faced with Herculean challenges, he was dedicated to finding solutions not only for himself but for his broader communities. At various points in his life, that meant pushing back against a pre-Stonewall America that simply did not want gay men to exist, living openly in a same-sex couple decades before marriage equality, fighting for his own life and that of his community during the darkest days of AIDS, and ultimately making sure the Williams Institute was focused on those who needed the most support--including transgender people, LGBTQ people of color, and those living in poverty.

Born in 1943, the son of an elementary school principal and a cemetery superintendent, Stu started life as a gifted scientist and musician. In elementary school, Stu won science fair honors for building an electronic well, radio transmitter, electrocardiograph, and a five-foot robot that could "talk, swing its arms, and clutch things." He became a talented violinist in high school, playing in the Pennsylvania State Regional Orchestra. When he enrolled in the University of Miami in 1961, he declared a major in Physics and a minor in Math. He wrote of his plans to attend graduate school to become a nuclear physicist. In addition to the violin, he listed the piano, alto horn, and "building boats" as hobbies.

The crucible of homophobia of the 1950s and 60s meant the world never got to know the contributions of Stu, the scientist and musician. But he forged a path of service, nonetheless. He left the University of Miami and spent several years moving between the growing LGBTQ communities of New York City, San Francisco, and finally, Los Angeles, where he met Chuck Williams in 1967.

Stu talked about the risks of being gay at the time, including being attacked, entrapped by the police, and fired from a job. He spoke about California's Atascadero State Hospital, notorious in the United States as one of the worst facilities that would confine gay men and youth as "sexual deviants" for conversion therapy for indefinite periods of time. But he rode through those years on a motorcycle, frequently in red speedos on the way to some of the first LGBTQ restaurants in San Francisco.

In the 1980s, Stu was diagnosed with HIV and then AIDS. He tried a number of toxic medications and alternative therapies that would seem bizarre to anyone but the dying and desperate before more effective medications became available in the mid-1990s. Stu knew if those medications had become available even a year later, he would not have survived. But Stu did survive, beating the odds not only against AIDS but lung cancer and COPD, living a full life of over eight decades.

Stu did not take this borrowed time for granted. When the world dictated a life of loneliness, Stu created community. When the world punched down with homophobia, he helped forge a path forward not just for himself but for all LGBTQ people.

From the depths of the closet of the 1950s and 60s, Stu created his own family. His 50-year relationship with Chuck Williams was an act of devotion, courage, and resistance. It sets an example not just for same-sex relationships but for any relationship.

Stu created a larger family through entertaining and cooking. His holiday feasts, paella, and lasagna with bechamel sauce were legendary. While Chuck was holding forth in the living room, Stu was knitting people together over the stove and across a massive dining room table. Decades before Hallmark holiday movies had two male leads, Stu and Chuck refashioned and reclaimed America's most traditional of traditions for themselves and their friends: Thanksgiving dinner, gathering around a towering Christmas tree, camping in an RV, and tailgating at football games.

Stu defied the world not only by creating family but by making the personal political. In the 1970s, that included hosting some of the first events for LGBTQ politicians such as Joel Wachs. During the 1980s and 1990s, that meant supporting a number of HIV organizations, including working full-time for the AIDS Research Alliance. And in 2000, that meant Stu sending the initial email to Bill Rubenstein at UCLA School of Law, starting a conversation that would lead to the creation of the Williams Institute.

In 2001, Chuck and Stu's initial gift to found the Institute was the largest ever given to an academic institution for anything related to LGBT issues. They kept resetting that record over and over again. Stu was a champion for continuing to support the Williams Institute and for it to have an inclusive portfolio of work. His desire for inclusivity was perhaps never more evident than in the mid-2000s when he championed the Williams Institute to change its focus from "sexual orientation and the law" to "sexual orientation and gender identity and the law."

Since Chuck's passing in 2023, Stu has worked efficiently and tirelessly to support the Institute with Chuck's estate and leverage that funding through matching gifts to create millions in additional support. Stu has left his own estate to the Williams Institute for the same purpose. In total, Chuck and Stu have given over $50 million to create a permanent endowment to fight myths and stereotypes about LGBTQ people through reliable research that supports policy change.

I had the honor to spend the last week of Stu's life with him. Just as he modeled how to live, he modeled how to die. During one of our final conversations, his thoughts were on his closest friends, on making sure the maximum amount of his estate would support the work of the Williams Institute, and expressing some humorous relief that he was getting out of Dodge before this next challenging period in our country's history.

For a couple of days before he died, Stu did not move his body much. But just before passing, he crossed both arms over his chest, placing each hand near the opposite shoulder, and then released one last exhale. Known as the "Lazarus sign," this reflex is sometimes thought to be why pharaohs have their arms crossed on sarcophagi. And that is how Stu left us, like royalty: dignified, strong, and controlled, ready to face the darkness.

But unlike Egyptian kings, Stu and Chuck did not bury their treasure with them. They gave everything they could to us, down to the widow's mite. By focusing the last decades of their lives on creating an institution to advance LGBTQ equality with a permanent endowment, Stu and Chuck anticipated this day when they would be gone, and the future would be up to us.

To honor their legacy, I know that they would want us first to gather friends around us next week to celebrate Thanksgiving and to make sure no one faces the holiday alone. Then, they would want us to fight on, even in the face of darkness.

Thank you, Stu. Thank you, Chuck. And thank all of you for being part of our family and our fight.

With much love and appreciation,

Brad

The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law is an academic research institute dedicated to conducting rigorous, independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy.

([link removed])

% link:[link removed] name="[link removed]" content="" %]

% link:[link removed] name="[link removed]" content="" %]

[Manage]([link removed]) your preferences | [Opt Out]([link removed]) using TrueRemove™

Got this as a forward? [Sign up]([link removed]) to receive our future emails.

View this email [online]([link removed]).

1060 Veteran Ave. Suite 134 | Los Angeles, CA 90095-7092 US

This email was sent to [email protected].

To continue receiving our emails, add us to your address book.

([link removed])

Message Analysis

- Sender: Williams Institute

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Emma