|

|

The 60 Minutes Controversy Shows We Forgot the Lessons of ‘Rathergate’

A scandal involving CBS News and electoral politics from 20 years ago has much to teach us about what’s happening in the media today

Donald Trump calls it “an UNPRECEDENTED SCANDAL” and “the Biggest Scandal in Broadcast history.” He’s talking about the allegation that “60 Minutes” edited its interview with Kamala Harris to make the vice president and Democratic candidate sound more presidential.

Most of the attention concerns Harris’ response to a question about whether Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is listening to America’s pleas to end the war in Gaza. In a teaser video, Harris sounded like a student who hadn’t done the reading before class—she meandered and buried her point. When “60 Minutes” aired, though, Harris gave a concise, well-considered response, more like a Ph.D. student defending a dissertation.

Did “60 Minutes” editors run interference for Harris to eliminate her word salad, or did they simply trim the 45-minute interview down to fit the 20-minute segment?

We would have a better idea if CBS released the full interview or a transcript, as several Republican lawmakers have urged and 85% of Americans want. But the news program’s actions so far and Trump’s response underscore that we have forgotten the lessons learned in a bigger scandal that unfolded on CBS almost exactly 20 years ago, if we ever learned those lessons at all.

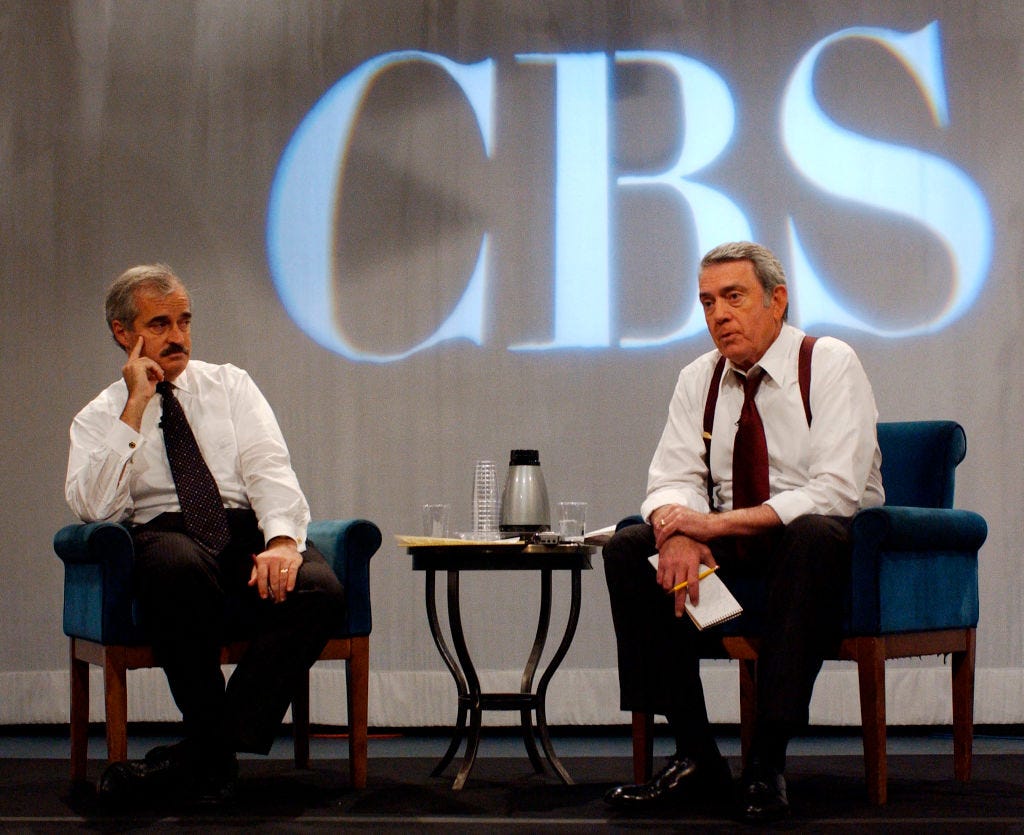

I’m talking about “Rathergate,” a controversy that began when CBS anchor Dan Rather dropped a bombshell less than two months before the 2004 election: that CBS had obtained memos casting doubt on then-President George W. Bush’s Vietnam-era service in the Texas Air National Guard (ANG). But fact-checking bloggers quickly revealed that those documents were probably fake.

This incident seems to be largely forgotten today. A Google Trends graph shows that hardly anyone has searched for keywords or people related to the story since 2005, although that may change given this latest kerfuffle at CBS News. Those who do remember Rathergate likely recall it as just another example of blatant media bias. That is what I thought for years. But this year, I have come to see it as something much more: a cautionary tale to anyone—whether a journalist, a blogger or just someone who reads the news—about what it will take to restore trust in America’s institutions.

Rathergate Broke a Story. Bloggers Broke It Down

Late in the summer of 2004, the CBS producer Mary Mapes met a former Texas national guardsman who had memos detailing shortcomings in Bush’s Texas ANG service. Signed by Bush’s commander, Lt. Col. Jerry Killian, the documents showed that Killian had been disappointed in the young Bush’s performance but that he faced pressure from the Texas ANG commander to “sugarcoat” his evaluation of the future president. Mapes saw this as confirmation of long-standing allegations that Bush got into the ANG thanks to his father’s political connections in order to keep him from having to serve in the Vietnam War. She and her colleagues rushed to break the story to the world.

On September 8, 2004, only six days after Mapes received a copy of the first memos, Rather revealed the documents on “60 Minutes Wednesday.” He said the memos had been “taken from” Killian’s personal file and that reporters had “consulted with a handwriting analyst and document expert who believes the material is authentic.”

The “60 Minutes Wednesday” team felt like they had blasted a home run. But the next day, they realized they’d actually hit a foul. Overnight, bloggers had started exposing problems with the documents. For starters, the memos looked like they had been written relatively recently, rather than 30 years ago. Specifically, the documents contained Times New Roman font, variable space between letters and a superscript “th” after numbers, all hallmarks of something typed in contemporary Microsoft Word rather than on a 1970s typewriter.

Over the next week, the story continued to fall apart. Critics pointed out anachronistic phrases and abbreviations in the memos. The commander supposedly pressuring Killian to fluff Bush’s record had retired more than a year before the memo supposedly was written. The man who provided the documents admitted that he had lied about how he got them. And the document examiners involved said the report overstated their confidence in the documents; in fact, they had told the reporters that they could not authenticate the documents since they had only seen copies rather than the originals.

Twelve days after running the original story, Rather admitted that he no longer had confidence in the memos and should not have used them. “We made a mistake in judgment, and for that I am sorry,” he said on television. After a panel reviewed the reporting on the story, Rather stepped down as anchor of CBS “Evening News,” and Mapes—a producer celebrated for breaking stories such as the American abuse of detainees at Abu Ghraib—was fired.

Taking Another Look

A couple years ago I began a deep dive into data about the collapse of trust in America. When a friend mentioned that Rathergate marked his moment of losing faith in the media, I realized I wanted to understand it better.

Since then, I’ve watched Rather’s hopeful interview with Killian’s secretary, who helped him argue that the documents were “fake but accurate.” But I also watched Rather’s apology and was stunned by the audible regret in his voice.

I studied the report that a CBS-appointed panel produced about the incident and learned how the story had come together. Earlier this year, I finally decided I wanted to know Mapes’ side of the story. So I read her 2005 book, “Truth and Duty: The Press, the President, and the Privilege of Power,” and saw the human element behind the headlines.

I believe that Rathergate is not a story about lying reporters or conspiracies to create fake news in order to win the election for the Democrats. Instead, it’s a cautionary tale about what can happen—what does happen—to any of us as we try to navigate the onslaught of information around us in a competitive and fast-paced environment.

The panel that investigated the incident concluded that political animus or bias was not the root cause of the mistaken story. Instead, “These problems were caused primarily by a myopic zeal to be the first news organization to broadcast what was believed to be a new story ... and the rigid and blind defense of the segment after it aired,” the panel wrote.

The panel concluded there was a “perfect storm” in which the proper vetting process fell short. “The combination of a new 60 Minutes Wednesday management team, great deference given to a highly respected producer [Mapes] and the network’s news anchor [Rather], competitive pressures, and a zealous belief in the truth of the segment seem to have led many to disregard some fundamental journalistic principles,” the panel wrote.

In other words, Mapes never tried to make fake news. Instead, she found information that completed a story she had been chasing for years about Bush’s ANG service. It confirmed something that many people in the press—who overwhelmingly identify with the Democratic Party and progressive politics—believed about Bush, that he had stumbled into the presidency through the privilege of his last name alone. This dynamic, coupled with competitive pressures to get the revelations out, resulted in her pushing to complete the story too quickly. And when things fell apart, her first reaction, and Rather’s, was to dig in.

Remembering Rathergate’s Lessons

Isn’t that what most of us do, though—at least sometimes? We process a massive amount of information on our televisions and smartphones, in our inboxes and our newsfeeds. We come across a graph or a news story that affirms a story or narrative percolating in our brain. We share it on social media without checking the facts—and maybe without even reading it, and we watch the likes roll in from others who agree. Someone fact-checks us, but we double down and cast doubt on those who contradict us. Wash, rinse, repeat.

It’s unfortunate when this happens in an individual’s social media feed, but the consequences become much more serious when this dynamic occurs in organizations that are supposed to be practicing journalism. And unfortunately, we have had too many Rathergate-like news stories in recent years.

The media’s treatment of Covington Catholic High School students—most notably Nick Sandmann—in 2019 stands out. The image of teenage boys in red Trump hats facing off against a Native American protester confirmed a narrative of rising racism, so the media ran with that story, only to have a very different view emerge once all the facts were in. Eventually, Sandmann sued and settled with several media corporations.

“The media’s reckless mishandling of the story stands as an important warning against the kind of agenda-driven, outrage-mongering clickbait that unfortunately thrives in the world of online journalism,” Reason writer Robby Soave wrote a year later. “But no less noteworthy was the news cycle that followed the initial flawed coverage, which featured a host of ideologically-motivated partisans doubling down on their initial assumption, digging for new information to justify it, and reassuring themselves that they were right all along.”

On the other side of the aisle, Fox News’ coverage supporting conspiracy theories about the 2020 election being stolen—including through allegations that vote tallies were rigged through voting machine manipulation—made for good ratings at the time because it confirmed what so many Trump Republicans thought. Because Fox executives knew the network was lying, this led to Fox’s $787 million payout to Dominion Voting Systems.

The faulty coverage of the Covington Catholic High run-in at the Lincoln Memorial and Fox’s reporting on the 2020 election took place on different sides of the aisle, but they share this in common: They both confirmed the narratives that the journalists or their audiences believed. And unlike in Rathergate, there seems to be no record of reporters or networks apologizing for their coverage, only spending money to end a lawsuit. No wonder trust in the media collapsed more in the Trump era than it did after the botched reporting about Bush.

What does this have to do with the vice president’s “60 Minutes” interview? For one, it shows that trimming a candidate’s words hardly registers on the scandal meter in comparison either to Rathergate or to the other cases of journalistic malpractice I’ve just cited. And that might be all there is to this story—after all, the only reason Trump can complain about the editing is that CBS published the full Netanyahu clip that Trump accuses the network of trying to hide.

But these stories also show that it is all too possible that someone at “60 Minutes” did run interference for Harris. If a journalist’s political leanings did play a role in deciding to show the Democratic candidate’s strongest answers during a popular, prime-time news show, it would be nothing new. And after Rathergate, it certainly shouldn’t be a surprise to CBS News.

This is why Americans deserve to have CBS release the full transcript, if not the full recording. Americans deserve to know what Harris said, how many times Bill Whitaker had to press her to get an answer that made sense and what else may have been cut out of the interview or done when the story was edited. As CBS should have learned in 2004, only transparency and faultless reporting can maintain trust as accusations fly online.

From CBS to Fox, the media would do well to think about the solutions that the post-Rathergate panel proposed: Establish standards, give someone power to enforce them and make no exceptions. When a news segment needs defending, make sure the defense is offered by someone other than the team that produced it. These practices ensure that zealous beliefs and political narratives don’t get in the way of reporting truth.

For those of us not in the news business, the lessons of Rathergate should also matter. Knowing our tendency to latch onto stories that confirm our priors, we can seek out and consume more ideologically diverse media. We can have compassion for reporters when they get something wrong, but we can also demand that they come clean and do better going forward. And whether in a college classroom, a local business, the dinner table or the town square, we can join conversations with people who disagree with us, rather than shut those conversations down and dig into our existing narratives. Only this robust exchange of diverse ideas can sharpen those ideas, help us find common ground and rebuild trust across our differences.

You’re currently a free subscriber to Discourse .