|

|

The Rise and Demise of the Great American Songbook

Unlike the dissonant anger and rage of recent music, the songbook offers both beauty and hard-won wisdom

By Martha Bayles

The music of the people is like a rare and lovely flower growing amidst encroaching weeds.—Antonin Dvořák

The Great American Songbook is the retrospective label for a body of music, from jazz standards to show tunes, largely created during the first half of the 20th century. Because it emerged alongside radio and recording, the Songbook includes not just written scores but performances by the finest singers and instrumentalists of the time, captured on wax cylinders, shellac discs and vinyl—and accessible today on compact discs and, of course, digitally. The wide range and varied beauty of this music are nicely captured in this passage from the renowned music critic Henry Pleasants. It is an encomium to Ella Fitzgerald, but it encompasses the Songbook as a whole:

She has a lovely voice, one of the warmest and most radiant in its natural range that I have heard in a lifetime of listening to singers in every category. She also has an impeccable and ultimately sophisticated rhythmic sense, and flawless intonation. Her harmonic sensibility is extraordinary. She is endlessly inventive. Her melodic deviations and embellishments are as varied as they are invariably appropriate. And she is versatile, moving easily from up-tempo scatting … to the simplest ballad gently intoned over a cushion of strings.

Taken as a whole, the Songbook is best understood as a singular artistic blossoming, comparable to the Zen ink art of 14th-century Japan, the plays and poetry of 16th-century England, the chamber music of 18th-century Austria, and the Impressionist painting of 19th-century France.

If this assertion sounds odd, it is probably because the latter four blossoms are considered high culture, while the Songbook is considered … what? Not low culture, surely. But not quite in the same class as Asian and European masterworks created by highly trained artisans for royal, noble and religious patrons, and treasured by subsequent generations for their beauty and significance.

As a lifelong student of American popular culture, I submit that this difference in cultural status is not about beauty or significance. It is about origins. Instead of being fashioned by elite artisans for elite patrons, the Songbook was produced by and for ordinary people, who supported the music not as patrons but as paying customers. And according to a long line of highbrow critics, Marxist critics, and (don’t forget) highbrow-Marxist critics, no cultural product sold for profit to the hoi polloi can ever be high culture—just as no peasant, proletarian or bourgeois can ever be an aristocrat.

But “culture” is one of those airy abstractions with so many meanings it might as well have none. So it is worth pondering its down-to-earth, even earthy, etymology. “Culture” comes from the Latin colere, meaning to tend or cultivate a field, garden or vineyard. That is why, even in our mediated, frictionless world, the most cultivated artists still have a little dirt under their fingernails. They know that the best blossoms require the most compost.

What kind of compost produced the Great American Songbook? According to the Alsatian-born historian Frédéric Louis Ritter, it was thin soil. Writing in 1884, he called “the American landscape ... silent and monotonous” because “the American farmer, mechanic, journeyman, stage-driver, shepherd, etc. does not sing.” Echoing Tocqueville, he blamed the Puritans, whose “emotional life” was so “stifled and suppressed,” there existed “no folk-poetry and no folk-songs in America,” only minstrel shows, brass bands and early vaudeville, which he found “vulgar, arrogant, and frivolous.”

From this account you would never know that this same soil was, at that very moment, germinating a new, world-conquering music. Called ragtime for its syncopated rhythm, it was seeded by Ernest Hogan, a Black Kentuckian who worked as a blackface minstrel after the Civil War.

Before the war, the vast majority of blackface minstrels were white men who smeared their faces with burnt cork and enacted stereotyped versions of the dance, music and humor of enslaved Blacks. The Black performers who, like Hogan, replaced these whites in the postbellum years were required to do the same. And although a few would eventually become famous enough to shed the blackface, the stereotypes persisted. So for good as well as ill, minstrelsy is an important layer in America’s musical compost.

Up From Minstrelsy

Born three years after the Civil War, Scott Joplin never wrote minstrel songs. Instead, this son of a formerly enslaved railroad worker (who played the fiddle) and a freeborn domestic worker (who sang and played banjo) is remembered as ragtime’s true cultivator. When Joplin’s father left the family, his mother struggled to feed her eight children. But she never stopped encouraging his musical education. So when a German-Jewish immigrant named Julius Weiss offered to tutor him free of charge, she gratefully accepted.

Ragtime was not the first American music to blend African-derived timbres and rhythms with European melodies and harmonies. Nor would it be the last. By the time Joplin died in 1917, that same cross-fertilization was nurturing an even more world-conquering music: jazz. The first green shoots appeared in the ethnic melting pot of New Orleans, but carried by riverboat, railroad and audio recording, jazz swiftly spread to the rest of the United States—and the world.

Which brings us to the Songbook, a hybrid of two distinct musical strains: jazz, dominated by Black innovators; and formal songwriting, dominated by immigrant Jews and “old stock” Anglo-Protestants. In the early days, many songwriters objected to jazz innovators who carried improvisation to the point of deconstructing the songwriters’ carefully crafted scores. But over time, those same songwriters came to revere jazz artists who knew how to enliven a song with just the right “swing” and melodic improvisation.

Please note that the hybridity I speak of is musical, not racial. This story includes classically trained Black songwriters such as Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, as well as innovative white jazz artists such as Gerry Mulligan and Bill Evans. Today, the Songbook is alive and well, as gifted musicians from around the world perform and update its repertoire. Its hybrid flowering is open to anyone blessed with talent, opportunity and the leisure for long practice.

But America being America, there have been endless disputes about whether Black or white artists deserve the most credit for the Songbook. These disputes can never be resolved because as Ralph Ellison once wrote, “To fashion a theory of American Negro culture ignoring the intricate network of connections which binds Negroes to the larger society … is to attempt a delicate brain surgery with a switch-blade.”

For many admirers, the Songbook’s first blossoming came to an untimely end in the 1950s, when the leading edge of the baby boomers traded musical quality for the cheap thrills of rock ’n’ roll. This criticism is not wrong. Compared to the efflorescence of Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, George Gershwin, Hoagy Carmichael, Duke Ellington, Richard Rodgers, Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer, most (not all) rock ’n’ roll songwriting is crabgrass. And compared to the rich vocalism of Ethel Waters, Louis Armstrong, Ethel Merman, Bing Crosby, Mildred Bailey, Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Peggy Lee and Judy Garland, most (not all) 1950s rock ’n’ roll singing is a thin reed.

But neither is this criticism of rock ’n’ roll fully correct. By the time Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley and Bill Haley came along, the Songbook was already past its prime. In the 1950s, some of the music purveyed as “pop” by the six major record labels adhered to the Songbook’s high standards. But a lot more did not. Drenched in syrupy string arrangements and slowed to a tempo that would put a rhinoceros to sleep, this kind of “pop,” later called “easy listening,” was so sluggish, only a sleep-walking rhinoceros could dance to it.

Hence the appeal of catchy, rootsy, toe-tapping rock ’n’ roll, itself a hybrid of rhythm & blues (R&B, the marketing label for Delta blues, electric blues, doo-wop, black gospel and soul); and country & western (C&W, the label for bluegrass, close harmony, white gospel and old-time banjo & fiddle). Right through the late 1960s, a roster of artists, some as gifted as their Songbook forebears, grew an array of new variants, all sharing the same tangled but nurturing roots.

Le Deluge

Then came the deluge. It’s a long story, but the upshot is that along with its other disruptions, the late-1960s counterculture broke the continuity of America’s deep-rooted musical tradition and replaced it with a very different sensibility that over time has proven sadly inferior.

One important if overlooked source of that break was the late-1950s, early-1960s art scene in New York. Not just on the fringes but at the center of that scene were several “experimental” figures who made names for themselves by recycling ideas and practices from such historic avant-garde movements as Grand Guignol in Paris, Expressionist theater in Berlin, Futurism in Milan and Moscow, and Dada in Zurich.

One of these movements was Fluxus, described in a 1963 manifesto by its founder, George Maciunas, as an effort to “Purge dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic art, mathematical art” from modern life, while also endeavoring to “promote living art, anti-art” and “NON ART REALITY.” (emphasis in original)

In practice, Fluxus was a mild retread of Dada, with some borrowings from the Theater of the Absurd (then in its heyday). But Fluxus got a PR boost in 1966 when Maciunas persuaded a tiny offbeat gallery in London to mount a one-woman show by a friend of his. The show was called “Unfinished Paintings and Objects,” and just before it opened, a world-famous musician walked in and decided to climb one of the artworks: a stepladder standing under a blank canvas suspended horizontally from the ceiling.

At the top of the stepladder, the musician found a spyglass, clearly intended to magnify a word written in tiny letters on the canvas above. Later, he would recall: “You’re on this ladder—you feel like a fool, you could fall any minute—and you look through [the spyglass] and it just says ‘YES’. … And just that ‘YES’ made me stay.”

By now the reader has probably guessed that the famous musician was John Lennon and the Fluxus-style artist his future wife and collaborator, Yoko Ono. Today, Ono is blamed for breaking up the Beatles, but by all reports, that breakup was underway well before she arrived on the scene. However, Ono was partly responsible for another, more serious break—the one that severed American music from its roots.

In recalling that day, Lennon also made it clear why he was charmed by Ono’s use of the word “Yes.” It was a welcome change, he said, from what everyone else was doing: “All the so-called avant-garde art at the time, and everything that was supposedly interesting, was all negative; this smash-the-piano-with-a-hammer, break-the-sculpture, boring, negative crap. It was all anti-, anti-, anti-. Anti-art, anti-establishment.”

This comment contains a painful irony. Ono may not have smashed anything in that exhibition. But when it came to bludgeoning music, she had no peer. Look it up on YouTube: In dozens of studio sessions, live performances and LP albums, the music of others is drowned out by Ono’s tuneless wailing, howling, bleating, yipping, grunting and screaming. In the short term, this “experimental” vocalizing is hard to endure. In the long term, it is enough to make the saints in heaven confess to the most abhorrent sins.

But Ono was hardly the only purveyor of “boring negative crap.” By the mid-1960s, a number of fringe rock bands were taking up the same “smash-the-piano-with-a-hammer” attitude. In 1965, the Velvet Underground traded its dark, expressive minimalism for 15 minutes of fame providing the cacophonous soundtrack to Andy Warhol’s multimedia “happening,” the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention were masters of the rock idiom but in the late 1960s did their best to deconstruct it (along with everything else). Following suit were Alice Cooper, Iggy Pop and countless others for whom the musical idiom they made their name with became another idol to be smashed.

In a moment, I will try to illustrate this point with a quick tour through the three Woodstock festivals: the original one in 1969, the 25-year anniversary in 1994, and the 30-year anniversary in 1999. But first, I must say something about the blues.

In 1930, the composer Aaron Copland complained that jazz was not capable of expressing the emotional heights and depths of the American experience. At the time, his point of comparison was the power of late-19th-century romantic music, which in Wagner and Mahler was reaching for emotion at its vastest and most oceanic—creating a whole world in a symphony, as Mahler famously said. The “two dominant jazz moods,” Copland wrote, were “the blues and the snappy number.” And neither was up to the job.

The best reply to this complaint is that no art form should be faulted for not doing what it never set out to do. The blues was created by a group of people who could ill afford to cultivate extreme emotion, especially negative emotion. The passionate intensity achieved in both blues and gospel is ritual in nature, evoked not as an end in itself but to help both performers and listeners get a grip, get over, get through another day.

This is why Ellison’s friend, critic and novelist Albert Murray, referred to the blues as “equipment for living.” Not just for Black people but for all people, the “blues idiom,” as Murray called it, combines two bedrock attitudes: “a sober acceptance of adversity as an inescapable condition of human existence” and “an affirmative disposition toward all obstacles.”

Say what you will about the 1960s counterculture, it placed no value on emotional restraint. Instead, it was about getting in touch with your passions and letting them all hang out, as the saying went. It was this liberationist ideal that persuaded the 1960s generation that Janis Joplin was a great blues singer. She did in fact have the talent to evolve in that direction. But she chose a different path, which was to cauterize her strong, three-octave voice by continual screaming.

According to her British biographer David Dalton, this was progress because it “detonated the hysteria latent in the blues … the violence, eroticism, craziness and spluttering of rage.” Dalton is right to say that in the classic blues, the passions are “codified and ironized.” But to treat this as a problem is to get it exactly backwards.

Joplin screamed her heart out at the original Woodstock. But most of her fellow performers—Richie Havens, the Band, Canned Heat, Creedence Clearwater Revival, the Grateful Dead, Arlo Guthrie, Santana, Sly & the Family Stone, Johnny Winter, Jimi Hendrix, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young—did no such thing. This is because they all came out of the same tradition, which encompasses blues, bluegrass, gospel, rockabilly, Latin jazz and vintage New Orleans jazz. Indeed, the latter was on display in the anti–Vietnam War anthem sung by Country Joe and the Fish, which was set to the tune of the “Muskrat Ramble,” a Kid Ory composition from 1926.

Down With “Peace and Love”

Today, what old and young find most memorable about Country Joe’s performance is not the catchy antiwar anthem but what preceded it: the famous “fish cheer,” which consisted of getting several thousand people to yell “F**k!” in unison. Believe it or not, the “fish cheer” was considered shocking at the time, but necessary to make the antiwar point.

Twenty-five years later, making political points was far less important than screaming and profanity. At Woodstock ’94 in Saugerties, New York, this was pretty much the norm, as the majority of the acts—Nine Inch Nails, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Cypress Hill, Alice in Chains, Henry Rollins—worked overtime to be as ear-bleedingly angry and outrageous as possible. And the crowd did the same, shoving and kicking one another in the mosh pit until the medical tent filled with casualties. (I know this because I was there and learned from a nurse that one young man had broken his back in two places.)

I skipped Woodstock ’99 because I had no desire to fry on the sizzling tarmac of a recently decommissioned air force base in Rome, New York. On video I watched Fred Durst, lead vocalist for the nu metal band Limp Bizkit, set the tone by roaring at the crowd of 220,000: “This is 1999, motherf**kers! Stick those Birkenstocks up your ass!” The heat, humidity, overflowing latrines and shortage of potable water made the crowd even more “angry and aggressive” than they wanted to be, according to Daniel Kreps of Rolling Stone.

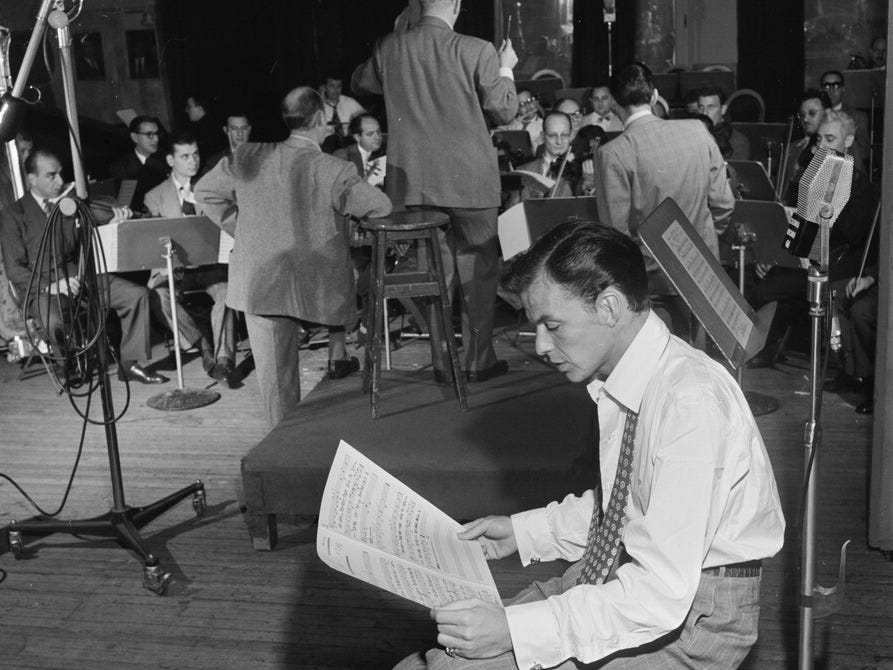

Kreps also reported a rash of sexual assaults and other violence on the tarmac, which Durst egged on by rapping obscenities, screaming and occasionally shrieking in a banshee voice that no human being, including Yoko Ono, would ever want to hear coming from his or her own mouth. Needless to say, this is about as far from, say, Sinatra with the Red Norvo Quintet as one could get.

Toward the end of Woodstock ’99, the mob, which had already been hurling projectiles at the stage and ripping the plywood sheathing off the sound relay towers, exposing the high-voltage equipment, proceeded to burn down every structure on the field. As Kreps concluded, “Woodstock ’99 devolved fully into Lord of the Flies.” It is significant that on the 50th anniversary of the original Woodstock in 2019, the alliance of groups trying to organize another concert fell apart amid quarrels, lawsuits and countersuits. And it is telling that none of the venues invited to host the event considered it worth the risk. “Peace and Love” was always a sappy slogan. But is “War and Hate” an improvement?

The anger that consumed popular music in the final three decades of the 20th century has now migrated elsewhere: to politics, the news media, and of course, the social media platforms that make their money by cranking up the “boring, negative crap” (to quote John Lennon again). And apart from a few superstars, some more impressive than others, musicians no longer occupy the beating heart of American culture. Taste is fragmented into billions of algorithmically curated playlists, and those who require bloody rage can find plenty of it in the deepest, most illicit corners of the web.

How did we Americans allow our world-conquering music to suffer such decay? In the 1990s heyday of shock metal, death metal, punk rock and gangsta rap (a subject for another essay), apologists, academics and advertisers alike insisted that this firehose of fury was cathartic because in the words of heavy metal producer Tom Werman, young people “need to be angry, they need to have music they can clench their fists by, to pump themselves up by. They're not always happy. They're confused and alienated. … They need an outlet.”

But what did this mean? Was Werman suggesting that young people were already angry, and the purpose of music was to help them cope, in the manner of the blues? Or was he saying that young people were not angry enough, and the purpose of music was to whip up more rage? If Werman meant the latter, and I fear he did, what good has all this whipped-up rage done? The past half-century has been full of stresses and strains, with no relief in sight. So it has become a cliché that the sober affirmation of the blues is passé, and the only authentic music is the kind that vents anger and despair by abusing innocent musical instruments, including the human voice.

If this cliché persists, it is doubtless because the world can seem a lot grimmer than it used to be, especially for middle-class youth looking back at the optimism of middle-class youth in the 1960s. But the roots of American music go deeper than that. Times were truly grim for the men and women who created ragtime, jazz, blues, gospel, swing, bebop, country and the rest. What can I say? The music they came up with can seem mercurial, spontaneous and unpredictable. But in fact it is highly disciplined, and to perform it well, an artist must be in full command of his or her faculties.

That goes double for the tradition’s finest flower, the Great American Songbook, which for all its joys expresses a hard-won wisdom still present in American culture, if you know where to look for it. That wisdom was well stated two millennia ago by Epictetus, the Stoic philosopher who had been a Roman slave: “It is difficulties that show what men are.”

You’re currently a free subscriber to Discourse .