Email

Tablets may be making it harder — not easier — to get books behind bars

| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Tablets may be making it harder — not easier — to get books behind bars |

| Date | September 16, 2024 2:47 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

The same two companies that got rich off prison phone calls are now focused on tablets.

Prison Policy Initiative updates for September 16, 2024 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Prison Banned Books Week: Books give incarcerated people access to the world, but tablets are often used to wall them off [[link removed]] Instead of taking advantage of their possibilities, the companies that got rich off prison phone calls offer limited book selections on tablets, as part of their continued efforts to sap money from incarcerated people and their families. [[link removed]]

by Mike Wessler and Juliana Luna

Books have long served as a bridge to the outside world for incarcerated people. They allow people cut off from their normal lives — and often from their families [[link removed]] — to engage with thinking and ideas that can open their mind and stories that transport them anywhere on earth and beyond. But carceral authorities have also always restricted access to books, and reading behind bars has only become harder in recent years.

This year’s Prison Banned Books Week [[link removed]] highlights the role tablets are ironically playing in further restricting incarcerated people’s access to reading materials. To better understand these changes, we looked at data collected by the Prison Banned Books Week campaign on prison book bans, policies around books, and the availability of ebooks on tablet computers. What we found is that tablets limit access to important modern writing and knowledge behind bars.

Tablets are nearly everywhere

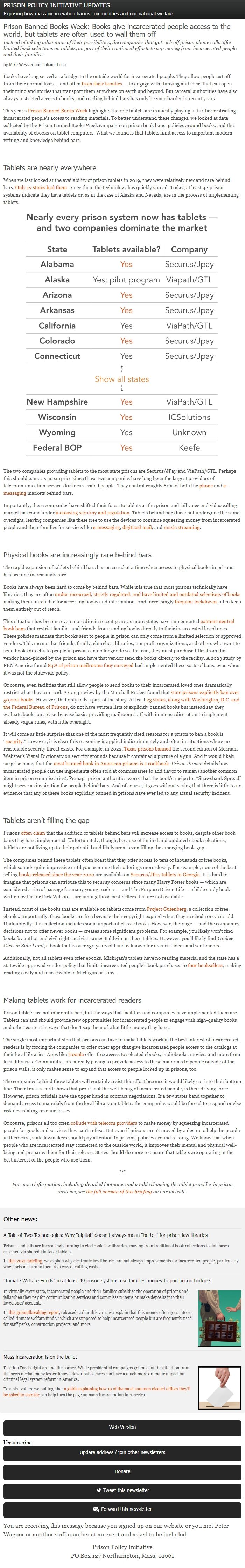

When we last looked at the availability of prison tablets in 2019, they were relatively new and rare behind bars. Only 12 states had them [[link removed]]. Since then, the technology has quickly spread. Today, at least 48 prison systems indicate they have tablets or, as in the case of Alaska and Nevada, are in the process of implementing tablets.

The two companies providing tablets to the most state prisons are Securus/JPay and ViaPath/GTL. Perhaps this should come as no surprise since these two companies have long been the largest providers of telecommunication services for incarcerated people. They control roughly 80% of both the phone [[link removed]] and e-messaging [[link removed]] markets behind bars.

Importantly, these companies have shifted their focus to tablets as the prison and jail voice and video calling market has come under increasing scrutiny and regulation [[link removed]]. Tablets behind bars have not undergone the same oversight, leaving companies like these free to use the devices to continue squeezing money from incarcerated people and their families for services like e-messaging [[link removed]], digitized mail [[link removed]], and music streaming [[link removed]].

Physical books are increasingly rare behind bars

The rapid expansion of tablets behind bars has occurred at a time when access to physical books in prisons has become increasingly rare.

Books have always been hard to come by behind bars. While it is true that most prisons technically have libraries, they are often under-resourced, strictly regulated, and have limited and outdated selections of books [[link removed]] making them unreliable for accessing books and information. And increasingly frequent lockdowns [[link removed]] often keep them entirely out of reach.

This situation has become even more dire in recent years as more states have implemented content-neutral book bans [[link removed]] that restrict families and friends from sending books directly to their incarcerated loved ones. These policies mandate that books sent to people in prison can only come from a limited selection of approved vendors. This means that friends, family, churches, libraries, nonprofit organizations, and others who want to send books directly to people in prison can no longer do so. Instead, they must purchase titles from the vendor hand-picked by the prison and have that vendor send the books directly to the facility. A 2023 study by PEN America found 84% of prison mailrooms they surveyed [[link removed].] had implemented these sorts of bans, even when it was not the statewide policy.

Of course, even facilities that still allow people to send books to their incarcerated loved ones dramatically restrict what they can read. A 2023 review by the Marshall Project found that state prisons explicitly ban over 50,000 books [[link removed]]. However, that only tells a part of the story. At least 23 states, along with Washington, D.C. and the Federal Bureau of Prisons [[link removed]], do not have written lists of explicitly banned books but instead say they evaluate books on a case-by-case basis, providing mailroom staff with immense discretion to implement already vague rules, with little oversight.

It will come as little surprise that one of the most frequently cited reasons for a prison to ban a book is “ security [[link removed]].” However, it is clear this reasoning is applied indiscriminately and often in situations where no reasonable security threat exists. For example, in 2022, Texas prisons banned [[link removed]] the second edition of Merriam-Webster’s Visual Dictionary on security grounds because it contained a picture of a gun. And it would likely surprise many that the most banned book in American prisons is a cookbook [[link removed].]. Prison Ramen details how incarcerated people can use ingredients often sold at commissaries to add flavor to ramen (another common item in prison commissaries). Perhaps prison authorities worry that the book’s recipe for “Shawshank Spread” might serve as inspiration for people behind bars. And of course, it goes without saying that there is little to no evidence that any of these books explicitly banned in prisons have ever led to any actual security incident.

Tablets aren’t filling the gap

Prisons often claim [[link removed]] that the addition of tablets behind bars will increase access to books, despite other book bans they have implemented. Unfortunately, though, because of limited and outdated ebook selections, tablets are not living up to their potential and likely aren’t even filling the emerging book-gap.

The companies behind these tablets often boast that they offer access to tens of thousands of free books, which sounds quite impressive until you examine their offerings more closely. For example, none of the best-selling books released since the year 2000 [[link removed]] are available on Securus/JPay tablets in Georgia. [[link removed]] It is hard to imagine that prisons can attribute this to security concerns since many Harry Potter books — which are considered a rite of passage for many young readers — and The Purpose Driven Life — a bible study book written by Pastor Rick Wilson — are among those best-sellers that are not available.

Instead, most of the books that are available on tablets come from Project Gutenberg [[link removed]], a collection of free ebooks. Importantly, these books are free because their copyright expired when they reached 100 years old. Undoubtedly, this collection includes some important classic books. However, their age — and the companies’ decisions not to offer newer books — creates some significant problems. For example, you likely won’t find books by author and civil rights activist James Baldwin on these tablets. However, you’ll likely find Yankee Girls in Zulu Land, a book that is over 130 years old and is known for its racist ideas and sentiments.

Additionally, not all tablets even offer ebooks. Michigan’s tablets have no reading material and the state has a statewide approved vendor policy that limits incarcerated people’s book purchases to four booksellers [[link removed]], making reading costly and inaccessible in Michigan prisons.

Making tablets work for incarcerated readers

Prison tablets are not inherently bad, but the ways that facilities and companies have implemented them are. Tablets can and should provide new opportunities for incarcerated people to engage with high-quality books and other content in ways that don’t sap them of what little money they have.

The single most important step that prisons can take to make tablets work in the best interest of incarcerated readers is by forcing the companies to offer other apps that give incarcerated people access to the catalogs at their local libraries. Apps like Hoopla [[link removed]] offer free access to selected ebooks, audiobooks, movies, and more from local libraries. Communities are already paying to provide access to these materials to people outside of the prison walls, it only makes sense to expand that access to people locked up in prisons, too.

The companies behind these tablets will certainly resist this effort because it would likely cut into their bottom line. Their track record shows that profit, not the well-being of incarcerated people, is their driving force. However, prison officials have the upper hand in contract negotiations. If a few states band together to demand access to materials from the local library on tablets, the companies would be forced to respond or else risk devastating revenue losses.

Of course, prisons all too often collude with telecom providers [[link removed]] to make money by squeezing incarcerated people for goods and services they can’t refuse. But even if prisons aren’t moved by a desire to help the people in their care, state lawmakers should pay attention to prisons’ policies around reading. We know that when people who are incarcerated stay connected to the outside world, it improves their mental and physical well-being and prepares them for their release. States should do more to ensure that tablets are operating in the best interest of the people who use them.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes and a table showing the tablet provider in prison systems, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: A Tale of Two Technologies: Why “digital” doesn’t always mean “better” for prison law libraries [[link removed]]

Prisons and jails are increasingly turning to electronic law libraries, moving from traditional book collections to databases accessed via shared kiosks or tablets.

In this 2020 briefing [[link removed]], we explain why electronic law libraries are not always improvements for incarcerated people, particularly when prisons turn to them as a way of cutting costs.

"Inmate Welfare Funds" in at least 49 prison systems use families' money to pad prison budgets [[link removed]]

In virtually every state, incarcerated people and their families subsidize the operation of prisons and jails when they pay for communication services and commissary items or make deposits into their loved ones' accounts.

In this groundbreaking report [[link removed]], released earlier this year, we explain that this money often goes into so-called "inmate welfare funds," which are supposed to help incarcerated people but are frequently used for staff perks, construction projects, and more.

Mass incarceration is on the ballot [[link removed]]

Election Day is right around the corner. While presidential campaigns get most of the attention from the news media, many lesser-known down-ballot races can have a much more dramatic impact on criminal legal system reform in America.

To assist voters, we put together a guide explaining how 19 of the most common elected offices they'll be asked to vote for [[link removed]] can help turn the page on mass incarceration in America.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for September 16, 2024 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Prison Banned Books Week: Books give incarcerated people access to the world, but tablets are often used to wall them off [[link removed]] Instead of taking advantage of their possibilities, the companies that got rich off prison phone calls offer limited book selections on tablets, as part of their continued efforts to sap money from incarcerated people and their families. [[link removed]]

by Mike Wessler and Juliana Luna

Books have long served as a bridge to the outside world for incarcerated people. They allow people cut off from their normal lives — and often from their families [[link removed]] — to engage with thinking and ideas that can open their mind and stories that transport them anywhere on earth and beyond. But carceral authorities have also always restricted access to books, and reading behind bars has only become harder in recent years.

This year’s Prison Banned Books Week [[link removed]] highlights the role tablets are ironically playing in further restricting incarcerated people’s access to reading materials. To better understand these changes, we looked at data collected by the Prison Banned Books Week campaign on prison book bans, policies around books, and the availability of ebooks on tablet computers. What we found is that tablets limit access to important modern writing and knowledge behind bars.

Tablets are nearly everywhere

When we last looked at the availability of prison tablets in 2019, they were relatively new and rare behind bars. Only 12 states had them [[link removed]]. Since then, the technology has quickly spread. Today, at least 48 prison systems indicate they have tablets or, as in the case of Alaska and Nevada, are in the process of implementing tablets.

The two companies providing tablets to the most state prisons are Securus/JPay and ViaPath/GTL. Perhaps this should come as no surprise since these two companies have long been the largest providers of telecommunication services for incarcerated people. They control roughly 80% of both the phone [[link removed]] and e-messaging [[link removed]] markets behind bars.

Importantly, these companies have shifted their focus to tablets as the prison and jail voice and video calling market has come under increasing scrutiny and regulation [[link removed]]. Tablets behind bars have not undergone the same oversight, leaving companies like these free to use the devices to continue squeezing money from incarcerated people and their families for services like e-messaging [[link removed]], digitized mail [[link removed]], and music streaming [[link removed]].

Physical books are increasingly rare behind bars

The rapid expansion of tablets behind bars has occurred at a time when access to physical books in prisons has become increasingly rare.

Books have always been hard to come by behind bars. While it is true that most prisons technically have libraries, they are often under-resourced, strictly regulated, and have limited and outdated selections of books [[link removed]] making them unreliable for accessing books and information. And increasingly frequent lockdowns [[link removed]] often keep them entirely out of reach.

This situation has become even more dire in recent years as more states have implemented content-neutral book bans [[link removed]] that restrict families and friends from sending books directly to their incarcerated loved ones. These policies mandate that books sent to people in prison can only come from a limited selection of approved vendors. This means that friends, family, churches, libraries, nonprofit organizations, and others who want to send books directly to people in prison can no longer do so. Instead, they must purchase titles from the vendor hand-picked by the prison and have that vendor send the books directly to the facility. A 2023 study by PEN America found 84% of prison mailrooms they surveyed [[link removed].] had implemented these sorts of bans, even when it was not the statewide policy.

Of course, even facilities that still allow people to send books to their incarcerated loved ones dramatically restrict what they can read. A 2023 review by the Marshall Project found that state prisons explicitly ban over 50,000 books [[link removed]]. However, that only tells a part of the story. At least 23 states, along with Washington, D.C. and the Federal Bureau of Prisons [[link removed]], do not have written lists of explicitly banned books but instead say they evaluate books on a case-by-case basis, providing mailroom staff with immense discretion to implement already vague rules, with little oversight.

It will come as little surprise that one of the most frequently cited reasons for a prison to ban a book is “ security [[link removed]].” However, it is clear this reasoning is applied indiscriminately and often in situations where no reasonable security threat exists. For example, in 2022, Texas prisons banned [[link removed]] the second edition of Merriam-Webster’s Visual Dictionary on security grounds because it contained a picture of a gun. And it would likely surprise many that the most banned book in American prisons is a cookbook [[link removed].]. Prison Ramen details how incarcerated people can use ingredients often sold at commissaries to add flavor to ramen (another common item in prison commissaries). Perhaps prison authorities worry that the book’s recipe for “Shawshank Spread” might serve as inspiration for people behind bars. And of course, it goes without saying that there is little to no evidence that any of these books explicitly banned in prisons have ever led to any actual security incident.

Tablets aren’t filling the gap

Prisons often claim [[link removed]] that the addition of tablets behind bars will increase access to books, despite other book bans they have implemented. Unfortunately, though, because of limited and outdated ebook selections, tablets are not living up to their potential and likely aren’t even filling the emerging book-gap.

The companies behind these tablets often boast that they offer access to tens of thousands of free books, which sounds quite impressive until you examine their offerings more closely. For example, none of the best-selling books released since the year 2000 [[link removed]] are available on Securus/JPay tablets in Georgia. [[link removed]] It is hard to imagine that prisons can attribute this to security concerns since many Harry Potter books — which are considered a rite of passage for many young readers — and The Purpose Driven Life — a bible study book written by Pastor Rick Wilson — are among those best-sellers that are not available.

Instead, most of the books that are available on tablets come from Project Gutenberg [[link removed]], a collection of free ebooks. Importantly, these books are free because their copyright expired when they reached 100 years old. Undoubtedly, this collection includes some important classic books. However, their age — and the companies’ decisions not to offer newer books — creates some significant problems. For example, you likely won’t find books by author and civil rights activist James Baldwin on these tablets. However, you’ll likely find Yankee Girls in Zulu Land, a book that is over 130 years old and is known for its racist ideas and sentiments.

Additionally, not all tablets even offer ebooks. Michigan’s tablets have no reading material and the state has a statewide approved vendor policy that limits incarcerated people’s book purchases to four booksellers [[link removed]], making reading costly and inaccessible in Michigan prisons.

Making tablets work for incarcerated readers

Prison tablets are not inherently bad, but the ways that facilities and companies have implemented them are. Tablets can and should provide new opportunities for incarcerated people to engage with high-quality books and other content in ways that don’t sap them of what little money they have.

The single most important step that prisons can take to make tablets work in the best interest of incarcerated readers is by forcing the companies to offer other apps that give incarcerated people access to the catalogs at their local libraries. Apps like Hoopla [[link removed]] offer free access to selected ebooks, audiobooks, movies, and more from local libraries. Communities are already paying to provide access to these materials to people outside of the prison walls, it only makes sense to expand that access to people locked up in prisons, too.

The companies behind these tablets will certainly resist this effort because it would likely cut into their bottom line. Their track record shows that profit, not the well-being of incarcerated people, is their driving force. However, prison officials have the upper hand in contract negotiations. If a few states band together to demand access to materials from the local library on tablets, the companies would be forced to respond or else risk devastating revenue losses.

Of course, prisons all too often collude with telecom providers [[link removed]] to make money by squeezing incarcerated people for goods and services they can’t refuse. But even if prisons aren’t moved by a desire to help the people in their care, state lawmakers should pay attention to prisons’ policies around reading. We know that when people who are incarcerated stay connected to the outside world, it improves their mental and physical well-being and prepares them for their release. States should do more to ensure that tablets are operating in the best interest of the people who use them.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes and a table showing the tablet provider in prison systems, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: A Tale of Two Technologies: Why “digital” doesn’t always mean “better” for prison law libraries [[link removed]]

Prisons and jails are increasingly turning to electronic law libraries, moving from traditional book collections to databases accessed via shared kiosks or tablets.

In this 2020 briefing [[link removed]], we explain why electronic law libraries are not always improvements for incarcerated people, particularly when prisons turn to them as a way of cutting costs.

"Inmate Welfare Funds" in at least 49 prison systems use families' money to pad prison budgets [[link removed]]

In virtually every state, incarcerated people and their families subsidize the operation of prisons and jails when they pay for communication services and commissary items or make deposits into their loved ones' accounts.

In this groundbreaking report [[link removed]], released earlier this year, we explain that this money often goes into so-called "inmate welfare funds," which are supposed to help incarcerated people but are frequently used for staff perks, construction projects, and more.

Mass incarceration is on the ballot [[link removed]]

Election Day is right around the corner. While presidential campaigns get most of the attention from the news media, many lesser-known down-ballot races can have a much more dramatic impact on criminal legal system reform in America.

To assist voters, we put together a guide explaining how 19 of the most common elected offices they'll be asked to vote for [[link removed]] can help turn the page on mass incarceration in America.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor