|

|

For Your Reference

In this week’s Editor’s Corner, Jennifer Tiedemann discusses her dual obsession with the ‘World Almanac’ and classic game shows

When I read Dan Rothschild’s recent Discourse essay talking about his childhood love of reference books, I had to laugh, because he might as well have been talking about me.

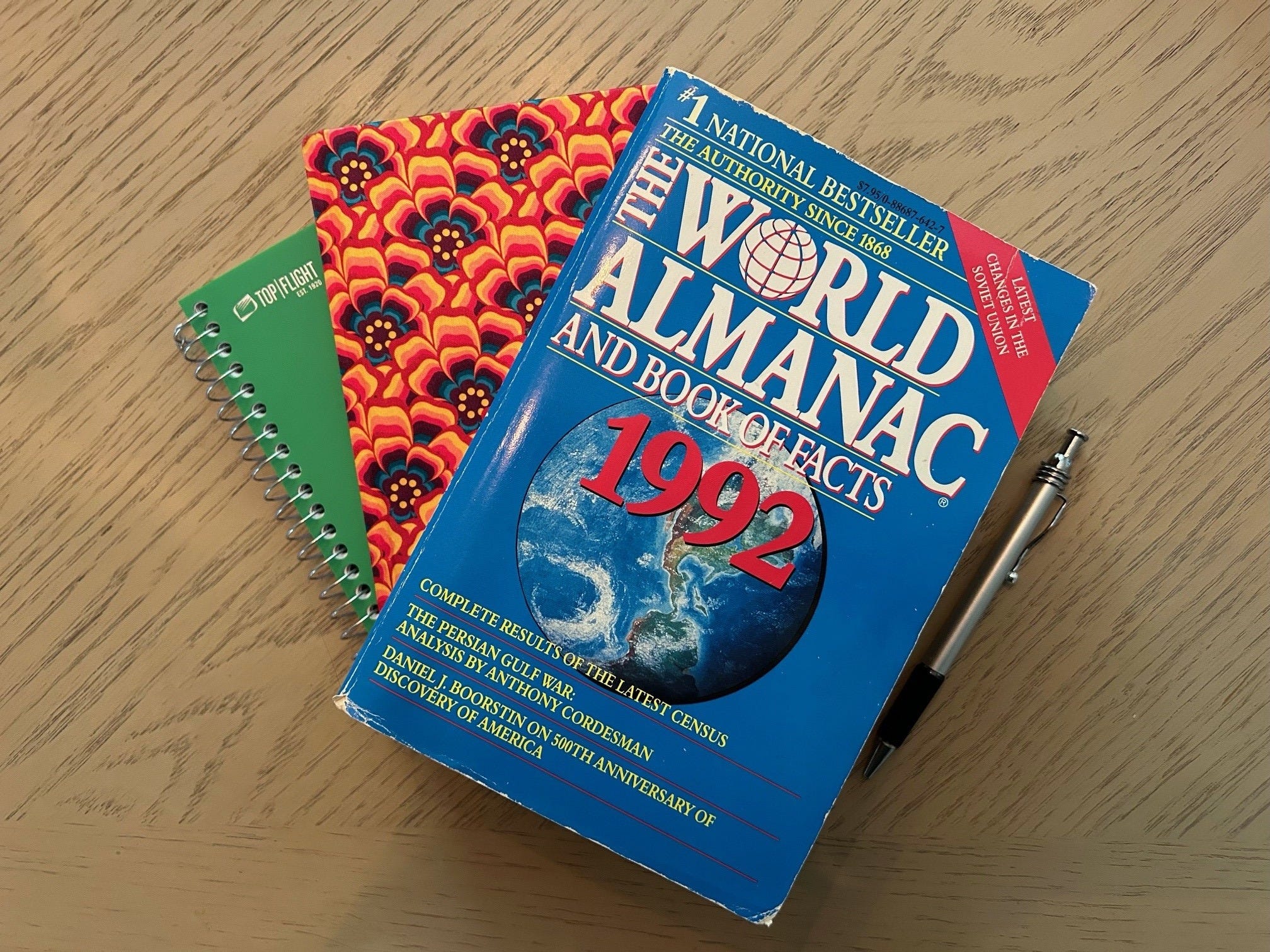

When I was about eight or nine, not too long after my family got our first home computer, I received a version of the computer game “Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego?” as a gift. Included in the box of floppy disks was the 1992 edition of “The World Almanac and Book of Facts,” which you were supposed to use to look up geographical information to help you in the game. As much as I liked the computer game, the “World Almanac” was the big winner here; I spent a lot of time with that book (I wasn’t really that different from the child who sets aside the toy to play with the box it came in).

Now, this was more than a bit inexplicable: To be honest, the “World Almanac” wasn’t exactly the sort of book you’d think would be interesting to a kid. Hundreds upon hundreds of pages of tiny type. Birth and death dates of famous people. Information about the year’s biggest news topics. Results from the 1990 Census. Have I put you to sleep yet?

But for some reason, I loved this book. I’m sure I eventually read every part of it, but it was far from cover-to-cover—I’d just open it up to a random page and see what it held for me. There was just so much to know! About everything! It was hard to believe that so much information could be held in such a relatively small paperback. (Apparently, in the 1980s, the “World Almanac” was produced by a staff of just 10 people; as a member of a small but mighty editorial team today, I have to say I have a bottomless respect for what they were able to put together.)

Until I read Dan’s essay, I really hadn’t considered why I might be a reference book fan. Rather than some strange idiosyncrasy of my own, it’s an interest that many others seem to share. Our interest in reference books is an insight into our personalities; Dan writes that as he grew up, “I found out that many of my friends (especially those who are weird and heterodox and maybe a little bit neuroatypical) gravitated to [reference books].” It sounds like Dan was describing me as a kid, for sure—and it’s clear that I’m not the only one who can identify with this sentiment.

But I think Dan really gets to the core of what I loved about the “World Almanac”: “You as the reader can make [reference books] comply with the demands of your knowledge, intellect and time constraints, not vice versa.” One thing that turns a lot of kids off from reading (including, honestly, myself) is its necessity. At least during the school year, I was reading lots of books that I didn’t choose and that I had to finish by a certain deadline. Now, it’s not that I didn’t like to read (I did become an editor, after all!), but I didn’t like to be obliged to read.

For me, reading the “World Almanac” was the exact opposite of an obligation—it was something I could get lost in because I wanted to. Whatever sorts of factoids I felt like reading about that day, I read about. If I felt like going down a certain rabbit hole, from the economy to offbeat stories, I could. Is it any wonder I like trivia nights as an adult?

Given how many people have read Dan’s essay (it’s one of our most popular recent pieces), many of you probably feel the same way about reference books as I do. And if misery loves company, maybe nerdiness does too.

Meanwhile ...

What I’m Watching: Lest you think that all I did for fun as a kid was read the “World Almanac,” I’ll have you know I also watched a lot of game shows. Sorry, Big Bird, but I learned to read by watching not “Sesame Street,” but “Wheel of Fortune.” I spent sick days as a kid cozying up to “The Price Is Right.” Even as an adult, I’m a big fan of watching ’70s and ’80s game shows. There are few better ways to spend an evening than trying to watch someone with big hair try to win a Daihatsu Charade on Alex Trebek’s “Classic Concentration.”

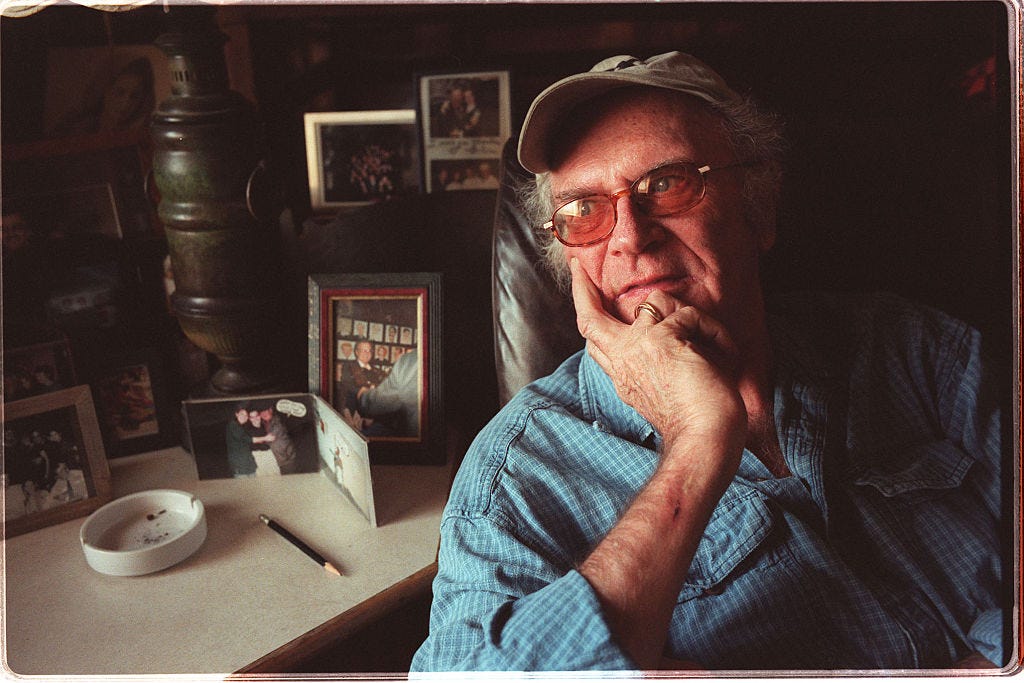

One of my favorite rewatches, though, is the ’70s classic “Match Game,” where a panel of six celebrities attempted to match a contestant’s fill-in-the-blank answer in an inane statement (“Peter said to Dumb Dora, ‘That’s not the TV you’re watching; it’s the _____!’”). The show was always good for a laugh—and a host of double entendres. Charles Nelson Reilly was a nearly ever-present panelist throughout the show’s run, and he was famous largely for, well, appearing on game shows (though younger Discourse readers might recognize him as the voice of the Dirty Bubble on “SpongeBob SquarePants”). With his Paul Lynde-ish campiness and his wicked sense of humor, he was a fan favorite.

But as with a lot of folks who seem like “one-trick ponies,” there’s a lot more to the story. Shortly before his death in 2007, Reilly performed a one-man show about his life that was a made into a feature film called, appropriately enough, “The Life of Reilly.” This, from the IMBD overview of the film, explains it better than I could: “If, in 1940, you had a lobotomized aunt, an institutionalized father, a racist mother, and were the only gay kid on the block, what do you think the odds would be that you’d end up a Tony winner, a staple of television, and a generational icon?” That’s what his performance is all about—you get to see how the man who often seemed like a caricature on TV and the stage was a real person with much to overcome.

It’s striking that Reilly spends very little time discussing the parts of his career that people are familiar with. Rather, he goes deeply into the joys and tragedies of growing up, living with a dysfunctional family and trying to get an acting career off the ground while facing significant hurdles. In doing so, he produces something very special—something truly hilarious, tear-jerking and literally jaw-dropping.

There’s only one drawback to watching the film, and that’s “watching the film”—finding it is not easy. The best way to watch it—really, the only way to watch it right now—is via a series of 28 clips of the movie on YouTube. Strung together, you can see the whole feature film. Ok, it may not be the easiest way to catch a movie, but trust me, you won’t regret going the extra mile to watch this fantastic and moving film.

Latest Stories

Christian Schneider, “Harris Leaves Trump Grasping for a Plan”

Robert Tracinski, “The Era of the Do-Nothing Congress”

Jon Gabriel, “We Need More Little Platoons”

David Masci, “We Need More Discourse”

Michael Puttré, “Life in Space Means Being Inside All the Time”

Christian Schneider, “Republicans Are Desperate To Join the Celebrity Culture They Abhor”

Addison Del Mastro, “Suing the City”

From the Archives

David Masci, “Different Candidate, Same Plan”

Jennifer Tiedemann, “The GOP-Conservative Breakup Is Officially Complete”

Ben Klutsey, “Pluralist Points: Acting Together While Thinking Differently”

You’re currently a free subscriber to Discourse .