| Know better. Do better. |  | Climate. Change.News from the ground, in a warming world |

|

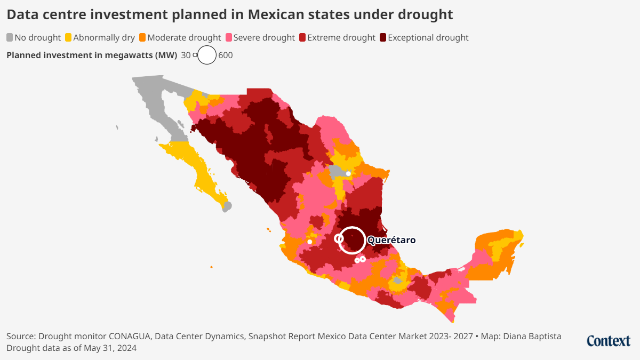

| | Data or crops?Dubbed Mexico's "data centre valley" by local politicians, the state of Querétaro in Mexico has attracted billions of dollars in investment from Microsoft, Google and Amazon.

With generous government incentives and an ideal location, near Mexico City and away from earthquake zones, the tech giants saw a new home for data centres in this semi-desert area.

But the region is also suffering from extreme drought. And data centres are thirsty.

Our data journalist Diana Baptista went to Colón, a municipality in the state, to report a new mini-documentary with video journalist Fintan McDonnell.

She found that many locals have been struggling with dead crops and water rationing, as an extreme two-year long drought has taken hold.

In nearby La Salitrera, a community of farmers and fishermen, dams are now nearly empty and tourist numbers have also fallen.

Huge data centres, meanwhile, generally use large amounts of water to cool their servers.  Drone shot of one of Microsoft's data centres located in the municipality of Colón, in Querétaro, México, June 17, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Miguel Tovar |

"There is no way of knowing how water is being distributed to those data centres. The only certainty is data centres are being

privileged over the citizens' well-being," said environmental activist Teresa Roldán.

She said more data centres would deepen the water shortage and unequal distribution of water in the region.

"If there is no water for the population, much less will there be water for the companies," she said.

With new data centre technology, companies say they are finding ways to use less water, such as using electricity for cooling.

And in Querétaro, the Secretary for Sustainable Development Marco del Prete is excited about the potential economic boost - he believes the new investments could create 20,000 indirect jobs.

But as their crops fail and they face daily water shortages, locals still do not know how much the companies are using. |

Pushing for answersContext received very limited information from the global firms and local authorities about exactly how much water they would use.

Microsoft said its data centres would only consume water "less than 5% of the year", Amazon Web Services said it had chosen "an air-cooled data centre design" instead of water cooling, and Google said it was partnering with environmentally responsible suppliers that would reduce its water consumption.

For now, Diana found many locals are not particularly aware of the issues, but tech firms know the potential controversies all too well.

Thomson Reuters Foundation/Diana Baptista |

In Uruguay's capital of Montevideo, for example, Google tried to open a data centre during a drought - planning to use 7.6 million litres of water a day, or about 10% of the city's water supply, according to activists.

After public pushback, the company created a new design using less water, but there is now concern that it could put more pressure on the electricity grid.

As demand for data surges with artificial intelligence, uncertainty remains around the specific local environmental impacts of the infrastructure needed to support it.

"It's somewhat ironic that there's not a lot of data on data centres," said Arman Shehabi, a scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Without that information, who will hold these firms to account for their impacts on communities like Colón?

See you next week,

Jack |

|

|

|