Email

New research links medical copays to reduced healthcare access in prisons

| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | New research links medical copays to reduced healthcare access in prisons |

| Date | September 4, 2024 2:33 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Many people in prison do not receive the most basic, necessary healthcare.

Prison Policy Initiative updates for September 4, 2024 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

New research links medical copays to reduced healthcare access in prisons [[link removed]] Using our prior research on prison wages and medical copays, researchers found that higher copays obstruct access to necessary healthcare behind bars, even as prison populations face increasing rates of physical and mental health conditions. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra

In most states, people incarcerated in prisons must pay medical copays and fees for physician visits, medications, dental treatment, and other health services. While these copays may be as little as two or five dollars, they still represent massive barriers to healthcare. This is because incarcerated people are disproportionately poor [[link removed]] to start with, and those who work typically [[link removed]] earn less than a dollar an hour and many don’t work [[link removed].] at all. A new report [[link removed]] published in JAMA Internal Medicine builds on our analyses of prison copay [[link removed]] and wage [[link removed]] policies across all state prison systems and the findings are clear: medical copays in prisons are associated with worse access to healthcare behind bars. These unaffordable fees are particularly devastating because they deter necessary care among an incarcerated population that faces many medical conditions — often at higher rates than national averages — and routinely faces inadequate health services behind bars.

In their recent publication, Dr. Lupez and her fellow researchers analyzed nationally representative data from state and federal prison populations published in the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Survey of Prison Inmates, 2016 [[link removed]]. While we previously published our own analysis [[link removed]] of the same dataset in 2021, this new research goes further by analyzing changes from the 2004 data and mapping our copays and wages data onto health data from people in prison. The researchers compared the 2004 and 2016 iterations of the Survey and found that, overall, people in prison are facing more chronic physical and mental health conditions than they were in 2004.

The findings are clear: medical copays in prisons are associated with worse access to healthcare behind bars.

Additionally, Dr. Lupez and her colleagues measured the effect of prison medical copays on access to specific healthcare services (including pregnancy-related care), access to clinicians for people with chronic physical conditions, and the continuation of medications for mental health. For each state, they used our 2017 copay and wage data to categorize each survey participant into one of three categories: no copays, copay amounts less than or equal to one week’s prison wage, and copay amounts greater than one week’s prison wage. Their results provide further evidence that medical copays limit access to care among the most vulnerable people in the system.

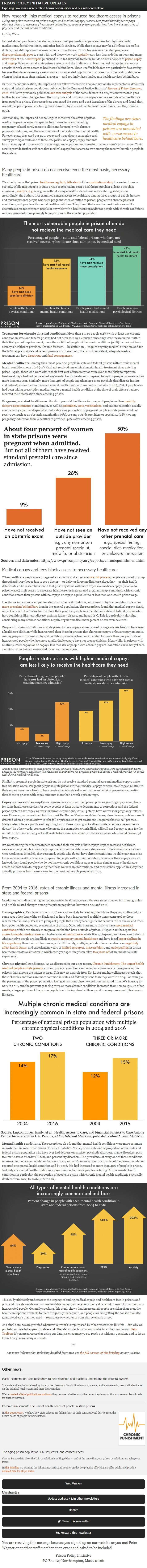

Many people in prison do not receive even the most basic, necessary healthcare

We already know that prison healthcare [[link removed]] regularly [[link removed]] falls [[link removed]] short [[link removed]] of the constitutional duty [[link removed]] to care for those in custody. While most people in state prison report having seen a healthcare provider at least once since admission, nearly 1 in 5 [[link removed]] have gone without a single health-related visit since entering state prison. Accordingly, the authors first examined general access to healthcare among three groups of people in state and federal prisons: people who were pregnant when admitted to prison, people with chronic physical conditions, and people with mental health conditions. They found that even the most basic care — like obstetric exams for pregnant people or any visit with a healthcare provider for people with chronic conditions — is not provided to surprisingly large portions of the affected population.

Treatment for chronic physical conditions. More than 1 in 10 people (14%) with at least one chronic condition in state and federal prisons had not been seen by a clinician since they were incarcerated. Within their first year of imprisonment, more than a fifth of people with chronic conditions (22%) had not yet been seen by a healthcare provider. Chronic diseases — by definition — require ongoing medical attention, and for the 62% people in state and federal prisons who have them, the lack of consistent, adequate medical treatment can have disastrous [[link removed]] and fatal [[link removed]] consequences [[link removed]].

Mental healthcare. Among the almost 400,000 people in state and federal prisons with chronic mental health conditions, one third (33%) had not received any clinical mental health treatment since entering prison. Again, those who were within their first year of incarceration were even more likely to report no treatment: 39% had not yet received any mental health treatment compared to 29% of people incarcerated for more than one year. Similarly, more than 41% of people experiencing severe psychological distress in state and federal prisons had not received mental health treatment. And more than one third (34%) of people who had been taking prescription medication for a mental health condition at the time of their offense had not received their medication since entering prison.

Pregnancy-related healthcare. Standard prenatal healthcare for pregnant people involves monthly doctor’s appointments [[link removed]] at minimum, as well as screenings [[link removed]], tests [[link removed]], vaccinations [[link removed]], and patient education usually conducted by a perinatal specialist. But a shocking proportion of pregnant people in state prisons did not receive so much as an obstetric examination (9%), see any outside providers or specialists (26%), or any pregnancy-education from a healthcare provider (50%) after entering prison.

Medical copays and fees block access to necessary healthcare

When healthcare needs come up against an arduous and expensive sick call process [[link removed]], people are forced to jump through arbitrary hoops just to see a doctor — or delay or forgo medical care altogether — as their health deteriorates. The researchers found that prison systems with more expensive medical copays (relative to prison wages) limit access to necessary healthcare for incarcerated pregnant people and those with chronic conditions more than prisons with no copays or copays equivalent to or less than one week’s prison wage.

Healthcare in prisons is subpar for almost any medical condition, and chronic physical conditions are often more prevalent behind bars [[link removed]] than in the general population. The researchers found that medical copays clearly impact access to healthcare for the more than 500,000 people incarcerated in state and federal prisons who have conditions like heart disease, asthma, kidney disease, and hepatitis C. This is particularly alarming considering many of these conditions require regular medical management or can even be cured.

People with chronic conditions in state prisons where copays exceed a week’s wage are less likely to have seen a healthcare clinician while incarcerated than those in prisons that charge no copays or lower copay amounts. Among people with chronic physical conditions who have been incarcerated for more than one year, 12% of incarcerated people who face more unaffordable copays have not seen a clinician. Meanwhile, in prisons with relatively lower copays or no copays, less than 8% of people with chronic physical conditions have not yet seen a clinician after being incarcerated for more than one year.

Among people incarcerated in state prisons for any amount of time, more unaffordable copays were associated with worse access to the necessary healthcare, like obstetrical examinations for pregnant people and seeing a medical provider for people with chronic medical conditions.

Similarly, pregnant people in state prisons do not receive standard prenatal care and medical copays make this situation worse. Pregnant people in state prisons without medical copays or with lower copays relative to their wages were more likely to have received an obstetrical examination and clinical pregnancy education than those in prisons with copay amounts more than a week’s prison wage.

Copay waivers and exemptions. Researchers also identified prison policies granting copay exemptions for some healthcare services for some people: at least 25 state departments of corrections and the federal prison system have copay waivers for chronic conditions, while 13 states have waivers for pregnancy-related care. However, as correctional health expert Dr. Homer Venters explains: “many chronic care problems aren’t detected when a person arrives [at the jail or prison], so to get treatment… requires the sick call process… Many systems have a practice of requiring two or three nursing sick call encounters before a person sees a doctor.” In other words, someone who meets the exemption criteria likely will still need to pay copays for the initial two or three nursing sick call visits before clinicians identify them as someone who should be exempt from copays.

It’s worth noting that the researchers repeated their analysis of how copays impact access to healthcare services among people without any reported chronic conditions in state prisons. If the chronic care waivers were working as intended, they reasoned, people who do not have chronic conditions would experience even lower rates of healthcare access compared to people with chronic conditions who have their copays waived. Instead, they found people who do not have chronic conditions appear to face similar rates of healthcare access as those who do, suggesting that these waivers are not routinely and consistently applied in a way that actually promotes healthcare access for the most vulnerable people in prison.

From 2004 to 2016, rates of chronic illness and mental illness increased in state and federal prisons

In addition to finding that higher copays restrict healthcare access, the researchers delved into demographic and health-related changes among the prison population between 2004 and 2016.

Demographics. People in prison in 2016 were more likely to be older; identify as Hispanic, multiracial, or some race other than white or Black; and to have been incarcerated multiple times compared to those incarcerated in 2004. These are groups of people that already face significant barriers to healthcare and often have poor health outcomes, even outside of prison. Older adults are more likely to have more medical conditions [[link removed]], which are already more prevalent behind bars. Outside of prison, Hispanic adults report less access to regular medical care [[link removed]] and higher rates of uninsurance [[link removed]], while Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native people are less likely to receive necessary mental healthcare [[link removed]] and have faced larger declines in life expectancy [[link removed]] than their white counterparts. Ultimately, multiple periods of incarceration can negatively affect health status [[link removed]], and experiencing years of limited resources [[link removed]], inaccessibility [[link removed]], and understaffing [[link removed]] in prison healthcare creates a situation in which each year spent in prison takes two years off [[link removed]] of an individual’s life expectancy.

Chronic physical conditions. As we discussed in our 2021 report, Chronic Punishment: The unmet health needs of people in state prisons [[link removed]], chronic physical conditions and infectious diseases are more prevalent in prisons than among the nation at large. This newest analysis from Dr. Lupez and her colleagues reveals that these chronic conditions are more common in state and federal prisons than they were in 2004. For example, the percentage of the prison population facing at least one chronic condition increased from 56% in 2004 to 62% in 2016, and the percentage facing three or more chronic conditions increased from 12% to 15%. In other words, a larger portion of the prison population is facing chronic illness, and in many cases multiple chronic illnesses.

Mental health conditions. The researchers also found that mental health conditions were more common in 2016 than in 2004. The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Survey offers data on the proportion of the state and federal prison population who have ever had depression, anxiety, psychotic disorders, manic disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and personality disorders. The prevalence of every one of these conditions increased in the prison population between 2004 and 2016: in 2004, nearly a quarter of the prison population reported one mental health condition and by 2016, this had increased to more than 40% of people in prison. Not only are mental health conditions more common, but more people are facing chronic mental health conditions in particular: the proportion of people in prison with chronic mental health conditions practically doubled from 2004 to 2016 (14% to 27%).

This study ultimately underscores the urgency of ending medical copays and healthcare fees in prisons and jails, and provides evidence that unaffordable copays put necessary medical care out of reach for far too many incarcerated people. Generally speaking, this study shows that incarcerated people are sicker than ever, the healthcare options available to them are grossly inadequate, and people are not getting the constitutionally-guaranteed care that they need — regardless of whether prisons charge copays or not.

As a final note, we are gratified whenever our work is repurposed by other researchers like this — it’s why we publish our detailed appendix tables and other data collections, many of which can be found in our Data Toolbox [[link removed]]. If you are a researcher using our data, we encourage you to reach out with any questions and to let us know how you are using our work.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Mass Incarceration 101: Resources to help students and teachers understand the carceral system [[link removed]]

Students and teachers are heading back to the classroom. In addition to math, science, and language arts, many will also focus on the criminal legal system and mass incarceration.

We’ve curated a list of publications and tools [[link removed]] they can use to better study the carceral system and that can serve as launchpads for further research.

Chronic Punishment: The unmet health needs of people in state prisons [[link removed]]

In this 2022 report [[link removed]], we show how state prisons are falling short of their constitutional duty to meet the health needs of people in their custody.

The aging prison population: Causes, costs, and consequences [[link removed]]

Census Bureau data show the U.S. population is getting older .— and at the same time, our prison populations are aging even faster.

In this briefing [[link removed]], we examine the inhumane, costly, and counterproductive practice of locking up older adults and provide detailed data for all 50 states [[link removed]].

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for September 4, 2024 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

New research links medical copays to reduced healthcare access in prisons [[link removed]] Using our prior research on prison wages and medical copays, researchers found that higher copays obstruct access to necessary healthcare behind bars, even as prison populations face increasing rates of physical and mental health conditions. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra

In most states, people incarcerated in prisons must pay medical copays and fees for physician visits, medications, dental treatment, and other health services. While these copays may be as little as two or five dollars, they still represent massive barriers to healthcare. This is because incarcerated people are disproportionately poor [[link removed]] to start with, and those who work typically [[link removed]] earn less than a dollar an hour and many don’t work [[link removed].] at all. A new report [[link removed]] published in JAMA Internal Medicine builds on our analyses of prison copay [[link removed]] and wage [[link removed]] policies across all state prison systems and the findings are clear: medical copays in prisons are associated with worse access to healthcare behind bars. These unaffordable fees are particularly devastating because they deter necessary care among an incarcerated population that faces many medical conditions — often at higher rates than national averages — and routinely faces inadequate health services behind bars.

In their recent publication, Dr. Lupez and her fellow researchers analyzed nationally representative data from state and federal prison populations published in the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Survey of Prison Inmates, 2016 [[link removed]]. While we previously published our own analysis [[link removed]] of the same dataset in 2021, this new research goes further by analyzing changes from the 2004 data and mapping our copays and wages data onto health data from people in prison. The researchers compared the 2004 and 2016 iterations of the Survey and found that, overall, people in prison are facing more chronic physical and mental health conditions than they were in 2004.

The findings are clear: medical copays in prisons are associated with worse access to healthcare behind bars.

Additionally, Dr. Lupez and her colleagues measured the effect of prison medical copays on access to specific healthcare services (including pregnancy-related care), access to clinicians for people with chronic physical conditions, and the continuation of medications for mental health. For each state, they used our 2017 copay and wage data to categorize each survey participant into one of three categories: no copays, copay amounts less than or equal to one week’s prison wage, and copay amounts greater than one week’s prison wage. Their results provide further evidence that medical copays limit access to care among the most vulnerable people in the system.

Many people in prison do not receive even the most basic, necessary healthcare

We already know that prison healthcare [[link removed]] regularly [[link removed]] falls [[link removed]] short [[link removed]] of the constitutional duty [[link removed]] to care for those in custody. While most people in state prison report having seen a healthcare provider at least once since admission, nearly 1 in 5 [[link removed]] have gone without a single health-related visit since entering state prison. Accordingly, the authors first examined general access to healthcare among three groups of people in state and federal prisons: people who were pregnant when admitted to prison, people with chronic physical conditions, and people with mental health conditions. They found that even the most basic care — like obstetric exams for pregnant people or any visit with a healthcare provider for people with chronic conditions — is not provided to surprisingly large portions of the affected population.

Treatment for chronic physical conditions. More than 1 in 10 people (14%) with at least one chronic condition in state and federal prisons had not been seen by a clinician since they were incarcerated. Within their first year of imprisonment, more than a fifth of people with chronic conditions (22%) had not yet been seen by a healthcare provider. Chronic diseases — by definition — require ongoing medical attention, and for the 62% people in state and federal prisons who have them, the lack of consistent, adequate medical treatment can have disastrous [[link removed]] and fatal [[link removed]] consequences [[link removed]].

Mental healthcare. Among the almost 400,000 people in state and federal prisons with chronic mental health conditions, one third (33%) had not received any clinical mental health treatment since entering prison. Again, those who were within their first year of incarceration were even more likely to report no treatment: 39% had not yet received any mental health treatment compared to 29% of people incarcerated for more than one year. Similarly, more than 41% of people experiencing severe psychological distress in state and federal prisons had not received mental health treatment. And more than one third (34%) of people who had been taking prescription medication for a mental health condition at the time of their offense had not received their medication since entering prison.

Pregnancy-related healthcare. Standard prenatal healthcare for pregnant people involves monthly doctor’s appointments [[link removed]] at minimum, as well as screenings [[link removed]], tests [[link removed]], vaccinations [[link removed]], and patient education usually conducted by a perinatal specialist. But a shocking proportion of pregnant people in state prisons did not receive so much as an obstetric examination (9%), see any outside providers or specialists (26%), or any pregnancy-education from a healthcare provider (50%) after entering prison.

Medical copays and fees block access to necessary healthcare

When healthcare needs come up against an arduous and expensive sick call process [[link removed]], people are forced to jump through arbitrary hoops just to see a doctor — or delay or forgo medical care altogether — as their health deteriorates. The researchers found that prison systems with more expensive medical copays (relative to prison wages) limit access to necessary healthcare for incarcerated pregnant people and those with chronic conditions more than prisons with no copays or copays equivalent to or less than one week’s prison wage.

Healthcare in prisons is subpar for almost any medical condition, and chronic physical conditions are often more prevalent behind bars [[link removed]] than in the general population. The researchers found that medical copays clearly impact access to healthcare for the more than 500,000 people incarcerated in state and federal prisons who have conditions like heart disease, asthma, kidney disease, and hepatitis C. This is particularly alarming considering many of these conditions require regular medical management or can even be cured.

People with chronic conditions in state prisons where copays exceed a week’s wage are less likely to have seen a healthcare clinician while incarcerated than those in prisons that charge no copays or lower copay amounts. Among people with chronic physical conditions who have been incarcerated for more than one year, 12% of incarcerated people who face more unaffordable copays have not seen a clinician. Meanwhile, in prisons with relatively lower copays or no copays, less than 8% of people with chronic physical conditions have not yet seen a clinician after being incarcerated for more than one year.

Among people incarcerated in state prisons for any amount of time, more unaffordable copays were associated with worse access to the necessary healthcare, like obstetrical examinations for pregnant people and seeing a medical provider for people with chronic medical conditions.

Similarly, pregnant people in state prisons do not receive standard prenatal care and medical copays make this situation worse. Pregnant people in state prisons without medical copays or with lower copays relative to their wages were more likely to have received an obstetrical examination and clinical pregnancy education than those in prisons with copay amounts more than a week’s prison wage.

Copay waivers and exemptions. Researchers also identified prison policies granting copay exemptions for some healthcare services for some people: at least 25 state departments of corrections and the federal prison system have copay waivers for chronic conditions, while 13 states have waivers for pregnancy-related care. However, as correctional health expert Dr. Homer Venters explains: “many chronic care problems aren’t detected when a person arrives [at the jail or prison], so to get treatment… requires the sick call process… Many systems have a practice of requiring two or three nursing sick call encounters before a person sees a doctor.” In other words, someone who meets the exemption criteria likely will still need to pay copays for the initial two or three nursing sick call visits before clinicians identify them as someone who should be exempt from copays.

It’s worth noting that the researchers repeated their analysis of how copays impact access to healthcare services among people without any reported chronic conditions in state prisons. If the chronic care waivers were working as intended, they reasoned, people who do not have chronic conditions would experience even lower rates of healthcare access compared to people with chronic conditions who have their copays waived. Instead, they found people who do not have chronic conditions appear to face similar rates of healthcare access as those who do, suggesting that these waivers are not routinely and consistently applied in a way that actually promotes healthcare access for the most vulnerable people in prison.

From 2004 to 2016, rates of chronic illness and mental illness increased in state and federal prisons

In addition to finding that higher copays restrict healthcare access, the researchers delved into demographic and health-related changes among the prison population between 2004 and 2016.

Demographics. People in prison in 2016 were more likely to be older; identify as Hispanic, multiracial, or some race other than white or Black; and to have been incarcerated multiple times compared to those incarcerated in 2004. These are groups of people that already face significant barriers to healthcare and often have poor health outcomes, even outside of prison. Older adults are more likely to have more medical conditions [[link removed]], which are already more prevalent behind bars. Outside of prison, Hispanic adults report less access to regular medical care [[link removed]] and higher rates of uninsurance [[link removed]], while Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native people are less likely to receive necessary mental healthcare [[link removed]] and have faced larger declines in life expectancy [[link removed]] than their white counterparts. Ultimately, multiple periods of incarceration can negatively affect health status [[link removed]], and experiencing years of limited resources [[link removed]], inaccessibility [[link removed]], and understaffing [[link removed]] in prison healthcare creates a situation in which each year spent in prison takes two years off [[link removed]] of an individual’s life expectancy.

Chronic physical conditions. As we discussed in our 2021 report, Chronic Punishment: The unmet health needs of people in state prisons [[link removed]], chronic physical conditions and infectious diseases are more prevalent in prisons than among the nation at large. This newest analysis from Dr. Lupez and her colleagues reveals that these chronic conditions are more common in state and federal prisons than they were in 2004. For example, the percentage of the prison population facing at least one chronic condition increased from 56% in 2004 to 62% in 2016, and the percentage facing three or more chronic conditions increased from 12% to 15%. In other words, a larger portion of the prison population is facing chronic illness, and in many cases multiple chronic illnesses.

Mental health conditions. The researchers also found that mental health conditions were more common in 2016 than in 2004. The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Survey offers data on the proportion of the state and federal prison population who have ever had depression, anxiety, psychotic disorders, manic disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and personality disorders. The prevalence of every one of these conditions increased in the prison population between 2004 and 2016: in 2004, nearly a quarter of the prison population reported one mental health condition and by 2016, this had increased to more than 40% of people in prison. Not only are mental health conditions more common, but more people are facing chronic mental health conditions in particular: the proportion of people in prison with chronic mental health conditions practically doubled from 2004 to 2016 (14% to 27%).

This study ultimately underscores the urgency of ending medical copays and healthcare fees in prisons and jails, and provides evidence that unaffordable copays put necessary medical care out of reach for far too many incarcerated people. Generally speaking, this study shows that incarcerated people are sicker than ever, the healthcare options available to them are grossly inadequate, and people are not getting the constitutionally-guaranteed care that they need — regardless of whether prisons charge copays or not.

As a final note, we are gratified whenever our work is repurposed by other researchers like this — it’s why we publish our detailed appendix tables and other data collections, many of which can be found in our Data Toolbox [[link removed]]. If you are a researcher using our data, we encourage you to reach out with any questions and to let us know how you are using our work.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Mass Incarceration 101: Resources to help students and teachers understand the carceral system [[link removed]]

Students and teachers are heading back to the classroom. In addition to math, science, and language arts, many will also focus on the criminal legal system and mass incarceration.

We’ve curated a list of publications and tools [[link removed]] they can use to better study the carceral system and that can serve as launchpads for further research.

Chronic Punishment: The unmet health needs of people in state prisons [[link removed]]

In this 2022 report [[link removed]], we show how state prisons are falling short of their constitutional duty to meet the health needs of people in their custody.

The aging prison population: Causes, costs, and consequences [[link removed]]

Census Bureau data show the U.S. population is getting older .— and at the same time, our prison populations are aging even faster.

In this briefing [[link removed]], we examine the inhumane, costly, and counterproductive practice of locking up older adults and provide detailed data for all 50 states [[link removed]].

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor