|

Critical State: Danger for Doctors

If you read just one thing … read about a revealing incident in Kolkata!

As Johanna Deeksha and Christianez Ratna Kiruba write in Scroll, a recent violent incident in Kolkata can tell us something more about the dangers women doctors in India are forced to face.

“The rape and murder of a doctor in RG Kar hospital in Kolkata on August 9 has led to widespread protests by doctors and medical students across the country. They are demanding that the management of hospitals and college campuses provide them with better facilities and security,” they write.

The victim was asleep in the hospital’s seminar room, and so part of what is so horrifying to so many is the sense that this happened to the victim, but could have happened to any number of women.

Responses from institutions, some of which put the onus on female doctors, students, and staff to be extra careful or monitor their own behavior, further angered protesters. Women are explaining how there are systemic issues that need to be addressed for their safety and security, and that they currently work and live in fear of threats from both outside of and within the medical system, including sexual harassment from superiors, and with very few avenues for recourse.

If You Read More Than One Thing: The Calm That Follows

In +972, Tamer Nafar, a rapper, actor, and screenwriter from Lyd, writes of fear on the part of Palestinians citizens of Israel for what will happen when the war ends.

As Nafar puts it, “my fear is something else, which the Jewish Israelis standing in line cannot understand: not war so much as the calm that follows; not the roar of the fighter planes, but the silence they leave in their wake; not Iran, Hezbollah, or the two combined, but what Israel will be like on the ‘day after.’” In other words, the society Nafar will be left to live in and the other people living in it.

Palestinians citizens of Israel will have “to live beside the people who sexually abused Palestinian prisoners in the notorious Sde Teiman prison without punishment; beside the right-wing extremists who called them heroes and rallied to their defense,” writes Nafar. “We will be forced to live alongside hundreds of thousands of newly armed civilians, with M-16s slung over their shoulders and pistols tucked into their waistbands thanks to National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir’s expansion of gun licenses.” Nafar also expresses concern over what the men fighting in Gaza will do to women and children when they come back home.

Women’s Rights, Wronged

A UN committee found that Poland’s restrictive abortion law violated women’s rights, writes Alicja Ptak in Notes From Poland.

Per Ptak’s report, “Women in Poland face severe human rights violations due to the country’s restrictive abortion law, found the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)... The committee noted that the situation of women in Poland was further aggravated after a constitutional court ruling rendered abortion in cases of significant fetal deformities illegal.”

The committee went so far as to say that the situation in Poland constitutes gender-based violence and may even be torture. The report was made after a three year inquiry into allegations by NGOs: “In March 2019, KARAT Coalition (Koalicja KARAT), the Federation for Women and Family Planning (Federacja na Rzecz Kobiet i Planowania Rodziny) and the Center for Reproductive Rights first notified CEDAW of the systemic restriction on accessing abortion in Poland.” These allegations were added to later in 2019 as well as in 2020 to make clear that aiding abortion is criminalized in Poland and that pregnancy termination options are “extremely limited.”

Deep Dive: Turning Left in Southern Europe

José Pedro Lopes, in a recent article titled “Post-industrial alignment and class support for radical left parties in Southern Europe,” published in the journal of South European Society and Politics, identifies a pattern of post-industrial class support for the radical left. “Leveraging survey data,” Lopes writes, the article “shows class support for the radical left is linked to a horizontal distinction in the labor market based on work logic.”

The transition to post-industrial economies led to a realignment of partisan preferences in most advanced economies in the Western hemisphere, but attention, per Lopes, has mostly focused on mainstream and far-right parties. This article set out to understand “whether there is a post-industrial pattern of class support for the radical left, focusing on Southern Europe.”

By radical left parties, Lopes is referring to a family of parties to the left of social democracy. They oppose the current socioeconomic and political status quo and reject “contemporary capitalism,” instead embracing collectivism and redistribution of wealth, though of course there are degrees to which said parties actually reject capitalism in practice. Historically, Lopes writes, communist parties attracted production workers and farmers and some progressive members of the middle class, while left socialists stressed “post-materialist issues” and as such count “a considerable amount of new middle-class groups among their voters, as well as younger and more educated voters.” These parties have gone through significant changes over the 30 years since the fall of the Soviet Union — but, then, Western societies have changed in that time, too.

The article used data from the European Social Survey (ESS) and the Hellenic National Election Study (ELNES) to analyze the extent to which support for radical left parties in Portugal, Spain, and Greece from 2008 to 2020 could be explained by occupational class. This region made sense, Lopes argued, because of the success of radical left parties there, particularly since the Eurozone crisis. Lopes also felt that Southern Europe’s relatively larger production and service workforce and relatively smaller middle class made it worthy of consideration.

Lopes found that people with daily interaction with other people as part of their work, specifically as interpersonal workers, were significantly more likely to support radical left parties. As Lopes writes, “Because these occupations deal with human individuality (e.g. health and education sectors), are heavily reliant on communication, and focus on people-work (e.g. direct care of children or elderly), these employees are more likely to hold culturally progressive attitudes and accept diversity and solidarity as principles of life.”

These parties receive less support from what’s thought of as the traditional working class, which is to say production workers; instead, support for these parties “is also firmly grounded in sectors of the professional middle classes (technical and sociocultural professionals) and, to a lesser extent, in the ‘new working-class’ of service workers.”

Lopes suggests that future research should broaden the scope and include more recent developments, like the “electoral stagnation” of these parties in Spain and Portugal as the far right rises.

Show Us the Receipts

Marcus Andreopoulos looked at the future of Bangladesh now that Sheikh Hasina resigned and fled the country. As Andreopoulos put it, “a long road remains ahead for the people of Bangladesh. Hasina leaving was only half of the battle. The real challenge now lies in rebuilding a democratic system of government that can successfully avoid a descent into further polarization and violence.” Andreopoulos also considered what it might mean for India, Pakistan, China, and even the United States, which “cannot expect New Delhi to assist its strategic aims in the South China Sea if India faces suffocating pressure from Beijing along its own borders.”

Patrick Carver Fox argued that Kamala Harris and Tim Walz should, if elected, try to make America a global “Good Neighbor,” a reference to a policy from the early 20th century articulated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt: “I would dedicate this nation to the policy of the good neighbor, the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others,” he said in his inaugural address in 1933. Today, “A Global Good Neighbor policy can pursue a global network of alliances on the merits of America’s strengths rather than fears about our enemies,” focusing on climate change and more effectively working with other democracies.

Michael Fox reported on Prudentópolis, a small Brazilian town celebrating its ties to Ukraine. The town’s founders came from what is today western Ukraine in the 1890s. As Fox explained, “At the time, the new Brazilian Republic was actively soliciting immigrants to open up farmland and colonize the countryside. The founders of Prudentópolis came to escape poverty, and other waves of Ukrainians followed.” Today, they celebrate Ukrainian culture to remember their roots and that these links still exist — everyone in the town, per Fox’s reporting, is paying close attention to the war in Ukraine.

Well-Played

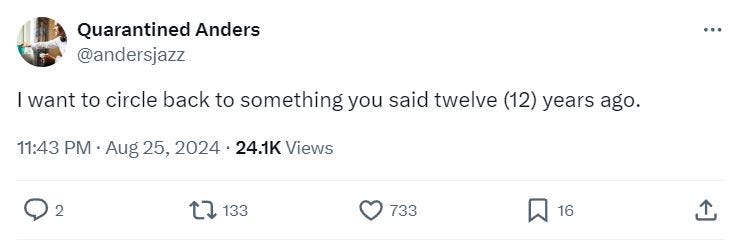

Just circling back.

To those who heed our warnings.

Sublime voice

So true, Pop Crave.

Could someone go check on Guillermo?

Please welcome to the stage…

Critical State is written by Emily Tamkin with Inkstick Media.

The World is a weekday public radio show and podcast on global issues, news, and insights from PRX and GBH.

With an online magazine and podcast featuring a diversity of expert voices, Inkstick Media is “foreign policy for the rest of us.”

Critical State is made possible in part by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

You're currently a free subscriber to Inkstick’s Substack. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.