|

|

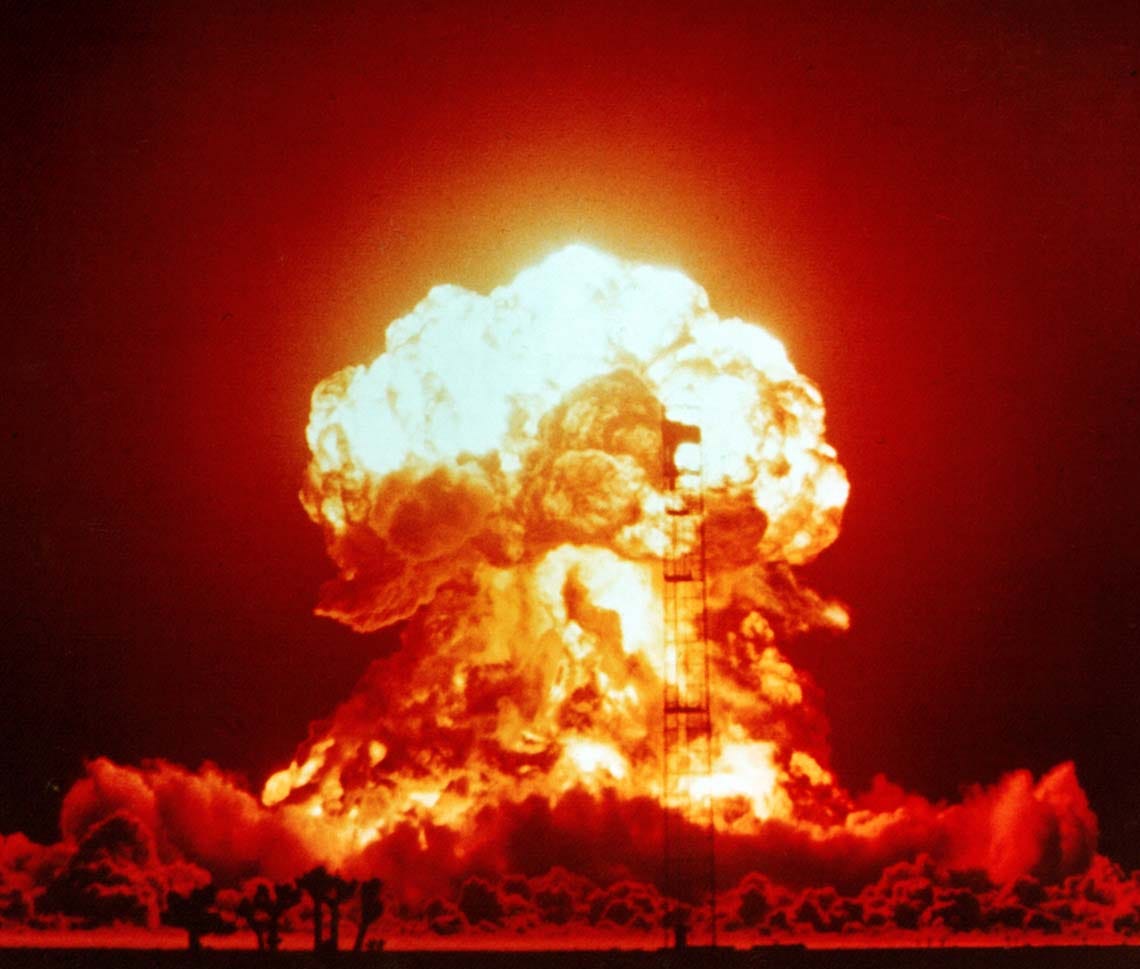

Learn To Worry and Love the Bomb

A recent book about the worst day ever reminds us we neglect nuclear deterrence at our peril

Lately, Annie Jacobsen’s “Nuclear War: A Scenario” has been getting a lot of attention in circles I pay attention to. So, when an old friend told me he was reading her book, I also decided to take the plunge.

Like my friend, I took nuclear strategy classes in college, e.g., National Security Policy, dubbed “Bombs and Rockets.” One of my professors was Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, who famously applied the expected utility theory of economic risk, gain and loss to issues of war and peace. Having come of age during the Cold War era, I also read a lot on the subject on my own, notably “The Third World War, August 1985“ by Gen. Sir John Hackett, and others of that ilk. Tom Clancy’s “Red Storm Rising” was sort of a pop “The Da Vinci Code” example of that genre.

My early issues with the Jacobsen book were the breathless description of the imagined nuclear strike on D.C. in lurid detail and her conceit that she was blowing the lid off mutually assured destruction, like it was some dark secret that she had only just uncovered rather than explicit American policy for seven decades. She writes:

How and why do U.S. defense scientists know such hideous things, and with exacting precision? How does the U.S. government know so many nuclear effects-related facts while the general public remains blind? The answer is as grotesque as the questions themselves.

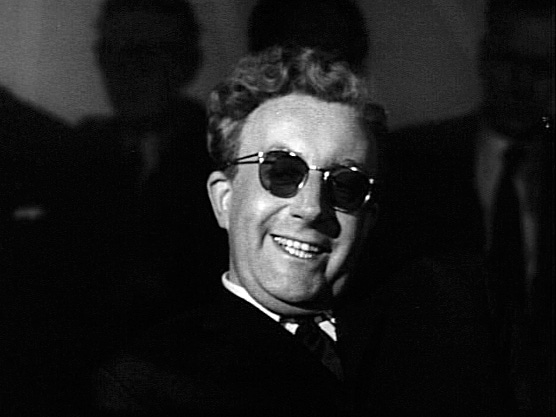

Did Jacobsen never see “Dr. Strangelove“?

Early on I became concerned that Jacobsen doesn’t quite get the distinction between war planning for practical use (such as plans to defend against a Soviet invasion of Western Europe) and war planning for possible use in order to maintain an effective deterrent (such as plans of action in a global thermonuclear war). The big secret of deterrence is you actually have to be willing and able to fight that war you’re trying to deter in order for the deterrence to be credible. That means submarines and bombers and missile silos and satellites and doctrine and trained personnel. The fact that we haven’t had any global thermonuclear wars to date seems to suggest deterrence has been working pretty well so far.

In fact, the biggest threat to nuclear deterrence is a nation’s leadership and culture failing to take it seriously. If anything, the popularity of Jacobsen’s book may serve to bring the idea that nuclear war is an ever-present threat that must be prevented back into the popular consciousness and priorities of our leaders.

The Final Countdown

There is little profit (expected utility?) in dissecting the technical elements of Jacobsen’s nuclear war scenario. Overall, her attention to detail is admirable. “Nuclear War” is meticulously researched, and indeed, the book is front-loaded with the names of dozens of political and military officials, scientists, academics and experts Jacobsen interviewed. The listing almost comes across as a prophylactic against possible criticism. The timeline of the attack and subsequent apocalypse is laid out with creditable descriptions of the systems and technologies that would be used.

In Jacobsen’s scenario, North Korea attacks out of the blue with an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) from its territory and a submarine-launched missile off the coast of California. The political situation is left undescribed. This allows the scenario to unfold as if on autopilot. While the North Korean missiles are in the air, Jacobsen has the U.S. respond with a 50-missile “launch on warning” strike on North Korea to decapitate the regime so it can’t launch more missiles.

I have to throw a flag here. Launch on warning has little to do with decapitating an enemy, whose leaders are presumably already sequestered somewhere when they initiate the attack. The point of this strategy is to fire your ground-based missiles while the enemy’s massive strike is in the air so those warheads land on your empty silos. Ideally your missiles will find more lucrative targets. The one-off, two-off attack from North Korea wouldn’t impose the sort of all-or-nothing pressure to respond with many missiles that a massive inbound flight of ICBMs would, which is what the nuclear strategists who conceived launch on warning had envisioned.

Jacobsen stresses launch on warning because this fast-forwards the timeline to Armageddon, which is the point of the book: All flights lead to the agonizing holocaust, as Tom Lehrer put it, an hour and a half from now. As it happens, there is an alternate strategy in the face of a first strike: Ride out the attack, where you presume the enemy will expend most of its weapons trying to take out your missiles, and thus your surviving weapons will be available for a more calculated retaliatory strike. Submarines are a key component of this strategy because they are likely to be the hardest nuclear-armed platforms to destroy preemptively.

Ultimately, these strategies are irrelevant in the titular “scenario.” A “bolt from the blue” strike involving a few land- and submarine-launched missiles triggers a massive U.S. retaliation, which is perceived by Russia as a general strike, and so they launch their missiles and kaboom! We’ll meet again some sunny day.

Jacobsen is not alone in having to bend over backwards to come up with a chain of events leading to the end of the world. The scenario put forth in the aforementioned “Third World War” by Hackett also required a lot of hand-waving in order to get us to the brink of doom. This is because it is very difficult to envision a situation where a rational power would attack another with nuclear weapons knowing it would be incinerated in return. I’ll get back to that point in a minute.

Shall We Play a Game?

One of the best recommendations of “Nuclear War” comes from a Hollywood screenwriter who publishes under the pseudonym George MF Washington at his Continental Congress Substack. Finding Jacobsen’s work “an engrossing, highly-technical story full of bracing details,” he is persuaded by the scenario’s plausibility that “the world ends because it has to … because that’s how the system is designed to work.”

Arguable. However, George MF Washington makes a wonderful observation that for him Jacobsen’s book conjures up memories of the 1983 movie “WarGames” starring Matthew Broderick and Ally Sheedy. In the finale, the rogue defense supercomputer, on the brink of launching a first strike on the Soviet Union, runs through a series of possible warfighting scenarios and determines that these are all futile. Concludes the supercomputer: “The only winning move is not to play.”

This sums up Jacobsen’s theme perfectly, although she seems horrified that the “game” exists at all. In fact, she spends interludes between her countdown-to-extinction chronicle describing how U.S. war planners and nuclear strategists gathered like witches at black masses to develop the machinery and doctrines that will lead inevitably to Armageddon if unleashed. Herein lies the main flaw of the book.

The problem is that Jacobsen conflates the madness of waging a nuclear war with the necessity of being able to because your potential adversaries can do likewise. She bemoans the trillions of dollars the U.S. has spent on its nuclear capability without dwelling on the fact that the Soviet Union (and Russia) has also, and that China is building up its capability now. The macabre dance of East and West in the development of nuclear forces and warfighting doctrines is intricate and goes unexamined in Jacobsen’s scenario.

More to the point, deterrence is waved away with a “deterrence having failed” remark so she can get to the action. The reader is left unsatisfied by unanswered questions. Why was North Korea not deterred? What was it trying to accomplish in the book? Is it undeterrable in reality?

This is perhaps the most chilling issue U.S. leaders may face: an undeterrable foe with nuclear weapons. If North Korea really is undeterrable, as Jacobsen’s scenario suggests, what should have been the proper U.S. course of action before the bolt from the blue arrived over Washington, D.C.? What if Iran is undeterrable?

Hopefully, we have a scenario for that.

You’re currently a free subscriber to Discourse .