|

|

Keeping the Faith

In our current hypersecular era, we seem to have forgotten that religion has a place in the public square

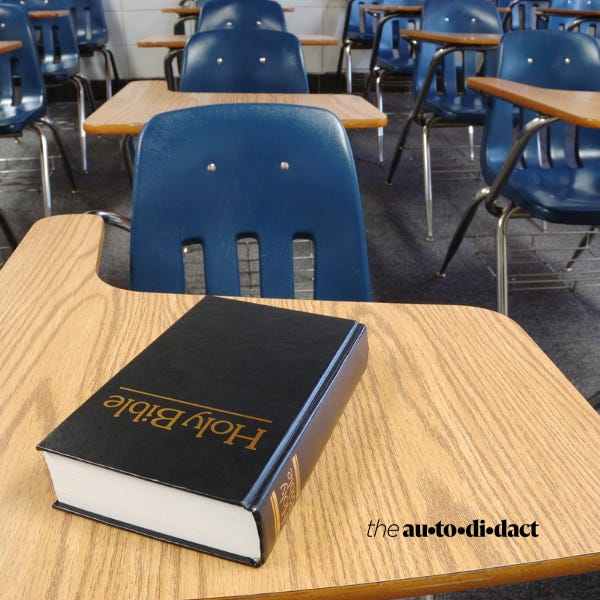

In June, Louisiana mandated that the Ten Commandments be displayed in every public school classroom. Just days later, Oklahoma went further, requiring schools to incorporate the Bible and the Ten Commandments into their curricula for grades five through 12. Nearly immediately, lawsuits were promised, and denunciations were fierce. The ACLU said, “the government should not be taking sides in this theological debate.” Interfaith Alliance called the laws “blatant religious coercion” and part of a “Christian nationalist agenda.”

For students of modern U.S. history, the episode felt familiar. The antireligious panic felt like a throwback to the 1960s, when freedom of religion began devolving into freedom from it. Campaigns against prayer in schools, city-hosted Christmas displays and the occasional mountaintop cross eventually won out. Today, in a country where 81% of residents believe in God, it’s somehow considered déclassé to mention Him in public.

But as Ryan Walters, Oklahoma’s state superintendent of public instruction, said, “the Bible is a necessary historical document to teach our kids about the history of this country, to have a complete understanding of Western civilization, to have an understanding of the basis of our legal system.” Basic knowledge of the Bible is essential to understanding the rest of Western literature, from Chaucer to Cormac McCarthy. Without it, history students can’t grasp the myriad allusions made by America’s founders, civil rights leaders—even politicians today.

Joe Biden’s Department of Education is fine with the Louisiana and Oklahoma changes, at least according to their official guidance on teaching religion in public schools. “Public schools may not provide religious instruction,” it states, “but they may teach about religion and promote religious liberty and respect for the religious views (or lack thereof) of all.” Later, the administration’s guidance approves “philosophical questions concerning religion, the history of religion, comparative religion, religious texts as literature, and the role of religion in the history of the United States.” Nothing Louisiana or Oklahoma has done runs afoul of these guidelines.

The Hypersecular Moment

The last half-century of hypersecularism is an oddity in American history. Our first public education law was created by the Massachusetts Bay Colony to ensure children could read the scriptures. Even famed atheist Richard Dawkins declared “a native speaker of English who has never read a word of the King James Bible is verging on the barbarian.”

Yet the antireligious panic boils over when even the slightest mention of faith enters the public square. Religion, or at least personal virtue, is as essential to the civil order as the Constitution itself—at least according to those who wrote it.

As John Adams wrote in 1798, “our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” A less-quoted line in that letter states, “we have no Government armed with Power capable of contending with human Passions unbridled by morality and Religion.”

For the past several decades, America has scrubbed every last indication of spiritual life from the public square. It has been replaced with a weird secular issue du jour based on the latest moral panic. One year it’s #MeToo, the next climate change, then Black Lives Matter, all under a rainbow flag with more stripes added all the time.

Since our “elite” culture views faith traditions as unseemly, government tries to maintain order by adding thousands of laws and tens of thousands of regulations. Browsing the headlines shows that doesn’t work—and never has. As Cicero wrote of ancient Rome, “the more laws a society has, the less justice.” A century later, the great Roman historian Tacitus rephrased it as, “the more corrupt the state, the more numerous the laws.”

Espousing Religion Versus Accepting Religion

Allowing public affirmations of faith is a far cry from an establishment of religion. No one is calling for mandated megachurch sermons ghost-written by D.C. bureaucrats. As an Orthodox Christian, I’d be the bearded guy in the back passing around wallet-sized icons and contraband incense.

The mere public acceptance of religion is by no means sectarian, let alone “Christian nationalist,” whatever that means. The U.S. has 54 different denominations of Baptists alone—good luck getting them or anyone else on the same page.

The reactionary fear of religion is simply laughable. Worship has been a constant feature of society at least since Göbekli Tepe was built on the Anatolian plains 11 millennia ago. It isn’t going away regardless of how many lawsuits are filed.

Thankfully, the secular absolutists remain the oddballs in a country that celebrates faith in all its diversity.

When my daughters were in elementary school, their best friends were sisters with the same age gap. We soon met their parents—Muslim immigrants from Tunisia—and often hung out together.

The first time they came for dinner, their father looked through my books and saw Bibles on the shelf. “Good, good,” he muttered. I asked him why he thought so.

“There’s a reason we like you guys. You believe in something.”

“No offense, but this country is crazy,” he laughed, then complained about whatever wokeness was called a dozen years ago.

We’ve shared similar experiences with Orthodox Jews. Our big, motley crew of friends jokingly calls ourselves the “Pan-Orthodox alliance”—conservative Christians, Jews and Muslims who agree on the big civic issues and work together to solve them. And none of us are afraid of one another’s beliefs—much as the founders intended.

They knew America’s success depended on the virtue of our people, not the virtue of our legislation. A good people courageously defends the rights endowed by their Creator, by ballot box or by defending our shores. But a crass citizenry would cede those rights for a fleeting sense of security. As Princeton’s Robert George explains, “people lacking in virtue could be counted on to trade liberty for protection, for financial or personal security, for comfort ... for having their problems solved quickly. And there will always be people occupying or standing for public office who will be happy to offer the deal.”

Since the framers knew man was selfish and imperfect, they found it ludicrous to entrust government with instilling virtue, let alone faith. They reserved that job for the individual, the family, the church—and yes, even educational institutions.

D.C. could add a million more laws, and it wouldn’t make people any more decent. Even our constitutional constraints will fail if citizens don’t understand how those constraints protect liberty, why that liberty is vital to our success and how to inculcate the ethics needed to maintain it. As James Madison put it, our Constitution requires “sufficient virtue among men for self-government.” Otherwise, “nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring one another.” The fact that we’ve conflated “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion” with the idea that the Bible shouldn’t even physically be in a public school classroom proves the point.

As President Washington wrote to a Rhode Island synagogue, our government “gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance,” and promised that “every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.” Perhaps future graduates of Louisiana and Oklahoma schools will know Washington was quoting Micah 4:4.

The free expression of religion in the public square might upset some people. That’s fine; free speech and a free press have the same effect. With all of these rights, Americans have the responsibility to accept those who dare disagree with them, whether in matters earthly or divine.

You’re currently a free subscriber to Discourse .