|

|

Close This Multitrillion-Dollar Budget Loophole

Congress needs a better baseline to evaluate legislation with a significant effect on the federal budget

As the federal government’s fiscal condition grows increasingly dire, budget watchdogs are contemplating how to reform federal budget processes to slow further deterioration. A good place to start would be to reform Congress’ scorekeeping rules to close a gaping loophole that has adverse effects reaching into the trillions of dollars. Specifically, the current scorekeeping baseline—which assumes enormous spending increases beyond what current law allows—should be supplemented with an additional baseline that does not assume these spending increases.

An Inadequate Baseline

Congress currently employs a specific set of rules for considering legislation with a significant budgetary impact. The projected effects of proposed legislation are compared to a scorekeeping baseline constructed by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) according to rules laid down in law. If the legislation would significantly increase federal deficits over 10 years, various procedural restrictions and points of order kick in. Grossly simplifying here, the gist of these rules is to make it harder to enact legislation that drives the deficit higher or lower without going through a privileged process known as budget reconciliation. Reconciliation cannot be used for nonbudgetary legislation but offers unique procedural advantages for provisions affecting the budget, among them reducing the threshold for passage from a three-fifths vote in the Senate to a simple majority. Congressional rules also establish procedural barriers against amendments offered within the reconciliation process that would further increase the deficit.

These budget rules depend on comparing a bill’s budgetary effects to the scorekeeping baseline, and therein lies the fundamental problem. The baseline is a patchwork of projection conventions, some of which reflect the operations of law, many of which do not. As a result, despite popular misconceptions to the contrary, current scorekeeping rules do not actually measure whether pending legislation worsens the fiscal outlook relative to current law.

It makes sense that many of the baseline’s assumptions deviate from actual law. For example, no federal funds can be spent without first being appropriated, which means that under current law, certain future federal spending levels technically revert to zero when relevant appropriations expire. Thus, if bills were evaluated relative to a strictly current-law baseline, any amount of appropriated spending beyond current expiration dates would be scored as worsening the deficit—even if that amount represented a sharp cut from current spending levels. Because of this, the scorekeeping rules instead direct CBO to compare proposed legislation to current levels of appropriations, adjusted for projected inflation, rather than to the zeroes in current law. CBO also assumes that instead of the current federal debt limit restraining future borrowing, it will be adjusted as necessary to avoid default. One could certainly find fault with these conventions, but it is necessary that some such conventions exist.

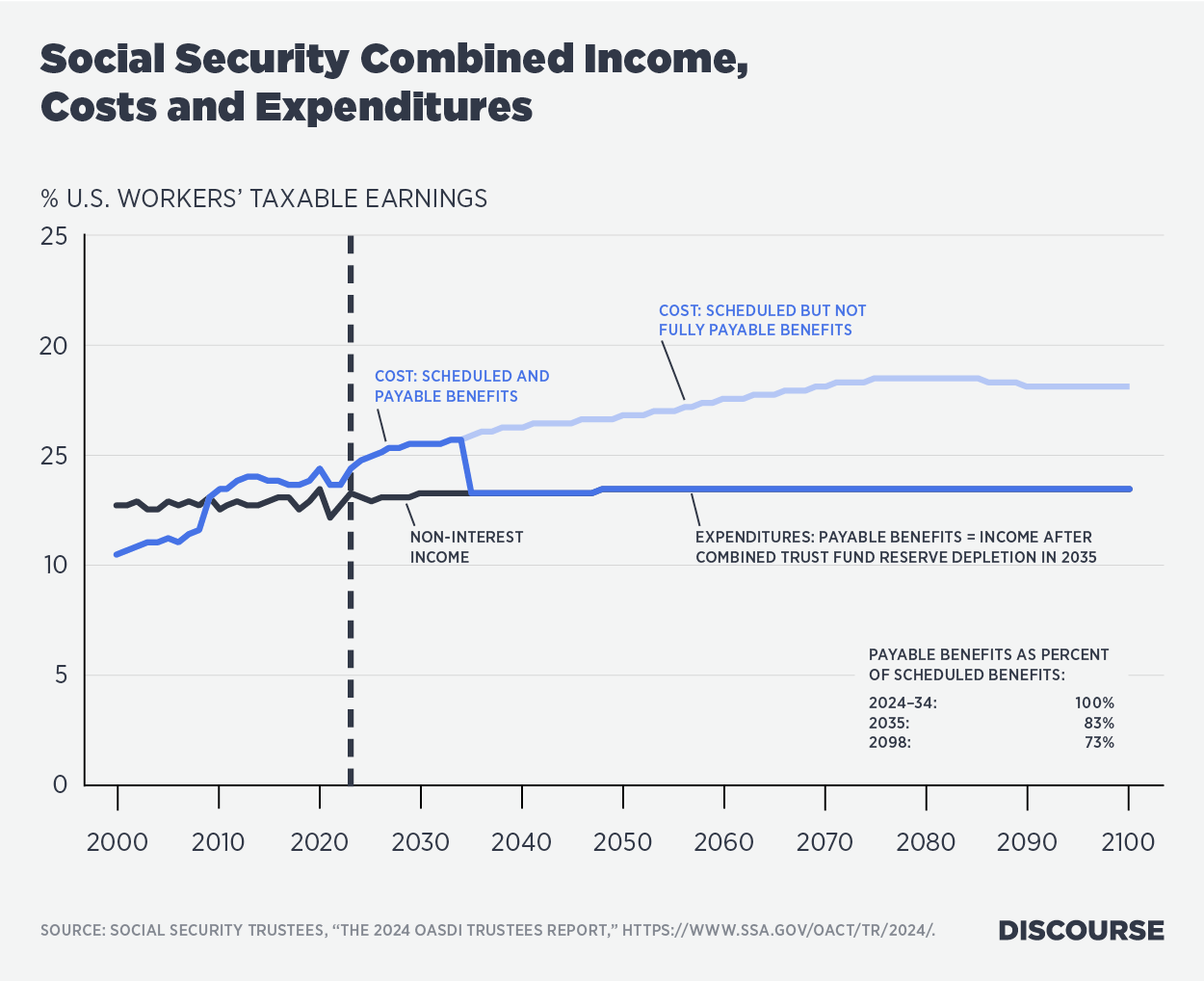

The scorekeeping baseline deviates from federal statute in one especially important way. By law, programs such as Social Security and Medicare are permitted to make benefit payments only from their trust funds. Social Security and Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) do not have the authority to borrow from or otherwise tap the federal government’s general fund. To the extent that these programs’ scheduled benefit obligations exceed the resources in their trust funds, those scheduled benefit obligations cannot be paid in full under current law. These restrictions exist because these are designed to be self-financing programs, funded by workers’ payroll tax contributions considered separately from the federal government’s general fund. If the programs’ tax revenue collections are inadequate to support benefit obligations, lawmakers are supposed to adjust benefit schedules, increase taxes or both, as necessary to close the shortfall. This was done for Social Security in 1983 and has been done several times for Medicare HI.

Congress’ scorekeeping procedures, however, ignore these important features of current law. The scorekeeping baseline assumes instead that all scheduled Social Security and Medicare benefits will be paid even when there is no statutory authority to do so. Similar inconsistencies exist with spending from other trust funds, such as the highway trust fund. (Note that Social Security and Medicare spending is automatically reauthorized from one year to the next; the issue with Social Security and Medicare, unlike annual appropriations, is not a lack of authorization but rather the spending level, which under law is determined by the amounts these programs’ trust funds can finance.) As it happens, this difference between the scorekeeping baseline and current law is enormous, because Social Security and Medicare benefit schedules currently exceed projected financing by trillions of dollars: The financing shortfall in Social Security alone over the next 75 years is estimated to be $22.6 trillion in present value.

CBO explains the discrepancy between the scorekeeping baseline and actual law as follows:

CBO’s baseline reflects the assumption that scheduled payments (for Social Security benefits, for example) will continue to be made in full after the funding source—namely, a program’s trust fund—has been exhausted, even if there is no legal authority to make such payments.

For now, I ask the reader to put aside the issue of what is likely to happen if Social Security and Medicare HI’s trust funds are actually depleted in the 2030s as currently projected. From a political perspective it is, of course, highly unlikely that lawmakers will simply sit back, take no action and allow Social Security old-age benefits to be cut 21% overnight due to trust fund inadequacy, as would occur under current law. What’s important for our purposes here is that there is a sharp deviation between the scorekeeping baseline and actual law.

Why the Loophole Is So Damaging

It is inherently troublesome for lawmakers to rely on a scoring baseline that assumes the spending of trillions of dollars beyond what current law permits. However, there are a number of specific respects in which this loophole causes real damage.

1. It’s inherently confusing to lawmakers, the press and the public that the scorekeeping baseline and actual law are so far apart. Because so much of the legislative process hinges upon comparisons with the scorekeeping baseline, it is inevitable that lawmakers, the press and the public will sometimes fundamentally mistake whether legislation increases or decreases the deficit.

2. It’s inconsistent. In some areas of the budget, notably tax law, CBO is directed to reflect current law in the baseline regardless of how politically unrealistic observers believe it to be. As CBO explains, “When taxes are scheduled to expire, those expirations are generally incorporated in the baseline projections.” For example, when income tax rates and alternative minimum tax thresholds were heading toward expiration at the end of 2012, few observers believed these tax provisions would all be permitted to expire, which would have caused a sudden, dramatic increase in federal tax collections. Nevertheless, scorekeeping rules still required CBO to construct its budget baseline on the assumption those tax policies would expire, as that was the literal reading of the law at that time.

For informational purposes, CBO and other budget watchdogs such as the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) also produced alternative baselines showing what was perceived to be a more realistic scenario in which existing tax policies were extended. Those alternative projections showed far larger deficits than the baseline did. However, these alternative projections were strictly informational: Congress’ official scorekeeping rules still compared pending legislation to the far more austere policy represented by the tax law expirations then in effect, no matter how unrealistic observers thought them to be.

It is inconsistent for Congress’ scorekeeping rules to make implicit political judgments on the spending side—namely, that sudden Social Security and Medicare spending cuts under current law are unrealistic and should be ignored—while on the tax side treating sudden, large tax increases as the letter of the law that must be respected. The scorekeeping rules should be consistent in treating both taxes and spending the same way.

3. It’s biased in the direction of higher spending and higher taxes. The scorekeeping baseline projects spending growth in Medicare and Social Security that well exceeds the rate of U.S. economic growth. For example, CBO’s long-term budget outlook currently projects that Social Security and Medicare spending will rise from 8.4% of GDP today to 11.3% of GDP in 2054. The baseline assumes this spending growth despite the fact that there is no legal authority for much of it. Effectively, the scorekeeping convention incorporates an assumption that lawmakers will change the law to permit much higher spending in the future, without charging lawmakers for increasing spending or worsening deficits if and when they do so. This assumption severely biases budget outcomes in the direction of perpetually rising spending, and it is a key reason why federal spending continues to grow faster than Americans’ earnings. At the same time, the scoring system inconsistently assumes current tax rates will expire, implicitly accepting higher future tax burdens.

4. It fails to treat impending Social Security and Medicare financing shortfalls with the urgency they warrant. Recurring reports from the CBO and other forecasters are very effective in drawing public and press attention to important policy problems that must be solved. For example, CBO’s publications of its near-term (10-year) and long-term budget outlooks consistently result in extensive coverage by news organizations, think tanks and advocacy groups. It is big news whenever these projections show an urgent problem, whether it’s projections of a weak economy, spiraling federal debt or a looming “fiscal cliff” threatening massive economic damage. The spotlight provided by reporters, experts and advocates in response to these projections helps to concentrate lawmakers’ attentions on addressing these problems.

But despite the facts that looming “cliffs” of Social Security and Medicare HI insolvencies are recognized in the annual reports of the Social Security and Medicare trustees, and referenced in other CBO publications, these reports simply do not precipitate the same demands for action as CBO’s baseline budget projections. A classic example of this discrepancy was the extremely limited public awareness in 2015-2016 that Social Security disability benefits almost came within a year of being interrupted. It’s unlikely to be coincidental that the public pays a lot of attention to the projected problems Congress’ scorekeeping baseline shows (such as rising federal debt) but comparatively little to effects it doesn’t show (such as interruptions of Social Security and Medicare’s spending authorities, and the benefit disruptions that would result from them).

5. It incentivizes irresponsible legislation and budget gimmicks. Perhaps the worst aspect of these scorekeeping conventions is that they not only allow for irresponsible and costly budget gimmicks but heavily incentivize them. In the past many mechanisms have been codified in law that were projected to hold down deficits even though most observers thought they were unrealistic—one example being sudden Medicare physician payment cuts pursuant to the old sustainable growth rate formula. Such provisions were indeed often overridden, but the historical evidence (compiled in this case by CRFB) shows that scoring such overrides as increasing the debt limited fiscal irresponsibility and sometimes (though certainly not always) prompted lawmakers to enact offsetting savings. Regardless of whether one considers the future implementation of cost-saving provisions of current law realistic, it is sound budgetary practice to charge lawmakers with increasing the deficit whenever they override them.

By contrast, because the scorekeeping baseline ignores statutory restrictions on Social Security and Medicare benefits, it invites the worst fiscal irresponsibility. It allows lawmakers to change the law to permit trillions in additional Social Security and Medicare spending beyond what current law permits, without such extremely irresponsible action even being acknowledged in a budget score. This is not a hypothetical concern. We have already seen preliminary instances of lawmakers exploiting this scoring loophole: For example, in 2010 the Affordable Care Act was inaccurately scored as reducing the deficit by double-counting its Medicare cost savings, once to extend Medicare HI solvency and a second time to offset a newly enacted health benefit. Also, in 2011-12, lawmakers increased Social Security’s spending authority by issuing over $200 billion in additional debt from the general fund to its trust funds. The same scorekeeping loophole that papered over these actions’ effects on the federal debt could just as easily be used to increase future Social Security and Medicare spending authority by trillions of dollars without lawmakers acknowledging these massive additions to the fiscal imbalance.

A Better Way

As problematic as the current scorekeeping baseline is, I do not suggest scrapping it. It has several important uses. One is that it discloses to lawmakers, the press and the public the extent to which unfunded Medicare and Social Security benefit obligations drive projections of untenable federal finances. Though these benefit obligations would not all be honored under current law, we should still understand their magnitudes, thereby better understanding the magnitudes of changes required in Social Security and Medicare to avoid a fiscal meltdown. CBO should continue to produce the current baseline, and certainly Congress’ budget processes should continue to inhibit legislation that would add to the deficits that CBO projects via these methods.

However, CBO should produce an additional scorekeeping baseline, accurately showing what Social Security and Medicare HI benefit payments will be when their trust funds are depleted under current projections. It would also make sense for this baseline to show the spending allowed under current law in other programs where the scorekeeping discrepancy exists, such as the highway trust fund. Just as there are procedural barriers and points of order against legislation that would add to deficits under CBO’s current baseline, the same barriers and points of order should lie against legislation that increases deficits relative to this more accurate baseline. CRFB has published articles showing how such a baseline might project future federal debt, though a more detailed baseline projection from CBO would also show other important specifics such as current-law outlays in Social Security and Medicare. Sen. Mike Braun (R-Ind.) and Rep. Ben Cline (R-Va.) also recently introduced a bill to create a new baseline that is similar in many respects, though differing in some details.

Several advantages would come from instituting this new baseline, and from inhibiting legislation that would increase deficits in relation to it. The first and most obvious is that it would be a more accurate baseline than the one currently in use, specifically more accurate with respect to Social Security and Medicare HI spending.

Second, it would provide a powerful early warning system to lawmakers, the press and the public to see the impending curtailment of Social Security and Medicare HI payments, especially when these are projected within the budget window.

Third, in the same way that current scorekeeping practices provide for a more responsible discussion of the consequences of extending expiring tax provisions, this new baseline would do the same for the consequences of extending mandatory spending authorities. This would reduce bias in the direction of higher spending.

Fourth, it would constrain costly budget gimmicks permitted under current procedures. In particular, it would inhibit lawmakers from increasing mandatory spending authority through the issuance of intragovernmental debt, or from double-spending the proceeds of cost savings in Medicare and/or Social Security. The corrected baseline would expose these actions as the additions to federal indebtedness that they are. By so doing, it would likely result in less federal indebtedness than would be generated using the current baseline alone.

In sum, if lawmakers wish to reform the budget process and close off a major avenue to fiscal irresponsibility, a good place to start would be to authorize a scorekeeping baseline that recognizes current statutory restrictions on Social Security and Medicare spending, and that makes it harder for lawmakers to increase federal deficits relative to that more accurate baseline.

You’re currently a free subscriber to Discourse .