| From | Critical State <[email protected]> |

| Subject | City of Lights (and Crackdowns) |

| Date | July 3, 2024 12:20 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

... read about Paris before the Olympics! Received this from a friend? SUBSCRIBE [[link removed]] CRITICAL STATE Your weekly foreign policy fix. If you read just one thing …

read about Paris before the Olympics!

In New Lines, Dalal Mawad offers a dispatch [[link removed]] from Paris before the Olympics — and it’s one about the repression of sex workers.

Sex work is not illegal in France: “In 2016, the country replicated what is known as the Nordic model for sex work, decriminalizing public solicitation of sexual services and punishing only the client who pays for sex. In the eyes of the law, the women are all victims and cannot be punished.”

However, most sex workers are undocumented migrants, and various NGOs shared that documentation control has increased. “These controls are being used to go after the women because the police cannot criminalize them as sex workers, only as undocumented foreigners,” Mawad explains.

This has meant that sex workers are not reporting cases of abuse by clients — like rape — to the police. They have also appeared less at NGOs that might provide support. As Mawad puts it, “They have become less visible and therefore more vulnerable.” And many fear that, given the rise of the country’s xenophobic far right, which performed well in the first round of the early parliamentary elections called by French President Emmanuel Macron, the crackdown won’t end with the Olympics.

Life Is But a Dream

In Noema, writer and musician Claire L. Evans looks at [[link removed]] lucid dreams, exploring the idea that consciousness is really on a spectrum between sleep and waking.

More than half of adults will experience a lucid dream at some point: “They’ll go to sleep, and as their REM cycles accumulate, as night shades into morning, as their sports car turns into a banana, they will suddenly realize, as I did: This is not real. This is a dream.” Evans also explains that lucid dreams are as old as the mind. “They’ve long been central to the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition, which teaches the cultivation of conscious awareness even in deep sleep. In the West, the philosophical literature of lucidity reaches back to Aristotle,” Evans writes. But modern science left them largely unexamined until well into the 20th century.

Now that there has been some research, we know that lucid dreams tell us something about consciousness. As Evans writes, “Dreaming and waking perception are both illusory; they’re models constructed by our brains that turn sensory stimulus, or its absence, into meaning. In waking life, short of a heavy psychedelic experience, that illusion is all-encompassing; there’s no other level of consciousness to ‘wake up’ into.” In lucid dreams, however, “we can examine the construction closely.”

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] Unerased

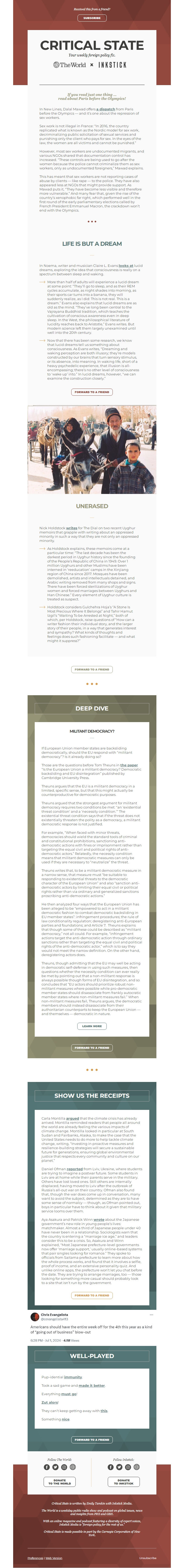

Nick Holdstock writes [[link removed]] for The Dial on two recent Uyghur memoirs that grapple with writing about an oppressed minority in such a way that they are not only an oppressed minority.

As Holdstock explains, these memoirs come at a particular time: “The last decade has been the darkest period in Uyghur history since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Over 1 million Uyghurs and other Muslims have been interned in ‘reeducation’ camps in the Xinjiang region of China since 2017. Mosques have been demolished, artists and intellectuals detained, and Arabic writing removed from many shops and signs. There have been forced sterilizations of Uyghur women and forced marriages between Uyghurs and Han Chinese.” Every element of Uyghur culture is treated as suspect.

Holdstock considers Gulchehra Hoja’s “A Stone Is Most Precious Where It Belongs” and Tahir Hamut Izgil’s “Waiting To be Arrested at Night,” both of which, per Holdstock, raise questions of “How can a writer fashion their individual story, and the larger story of their people, in a way that generates interest and sympathy? What kinds of thoughts and feelings does such fashioning facilitate — and what might it suppress?”

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] DEEP DIVE Militant Democracy?

If European Union member states are backsliding democratically, should the EU respond with “militant democracy”? Is it already doing so?

Those are the questions before Tom Theuns in the paper [[link removed]] “Is the European Union a militant democracy? Democratic backsliding and EU disintegration” published by Cambridge University Press.

Theuns argues that the EU is a militant democracy in a limited, specific sense, but that this might actually be counterproductive for democratic purposes.

Theuns argued that the strongest argument for militant democracy requires two conditions be met: “an ‘existential threat condition’ and a ‘necessity condition.’” The existential threat condition says that if the threat does not existentially threaten the polity as a democracy, a militant democratic response is not justified.

For example, “When faced with minor threats, democracies should wield the standard tools of criminal and constitutional prohibitions, sanctioning anti-democratic actions with fines or imprisonment rather than targeting the equal civil and political rights of anti-democratic actors.” Relatedly, the necessity condition means that militant democratic measures can only be used if they are necessary to “neutralize” the threat.

Theuns writes that, to be a militant democratic measure in a narrow sense, that measure must “be suitable to responding to existential threats to the democratic character of the European Union” and also “sanction anti-democratic actors by limiting their equal civil or political rights rather than via ordinary and generalized sanctions proscribing anti-democratic actions.”

He then analyzed four ways that the European Union has been alleged to be “empowered to act in a militant democratic fashion to combat democratic backsliding in EU member states”: infringement procedures; the rule of law conditionality regulation; deregistering anti-European parties and foundations; and Article 7. Theuns explains that though some of these could be described as “militant democracy,” not all could. For example, “infringement actions target the anti-democratic action through ordinary sanctions rather than targeting the equal civil and political rights of the anti-democratic actor,” which is to say they would not meet the narrow definition. On the other hand, deregistering actors does.

Theuns, though admitting that the EU may well be acting in democratic self-defense in using such measures, then questions whether the necessity condition can ever really be met by pointing out that a non-militant response is always possible though forms of EU disintegration, and so concludes that “EU actors should prioritize robust non-militant measures where possible while pro-democratic member states should disassociate from frankly autocratic member states where non-militant measures fail.” When non-militant measures fail, Theuns argues, the democratic members should instead disassociate from their authoritarian counterparts to keep the European Union — and themselves — democratic in nature.

LEARN MORE [[link removed]]

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] SHOW US THE RECEIPTS

Carla Montilla argued [[link removed]] that the climate crisis has already arrived. Montilla reminded readers that people all around the world are already feeling the various impacts of climate change. Montilla looked in particular at South Sudan and Fairbanks, Alaska, to make the case that the United States needs to do more to help tackle climate change, writing, “Investing in proactive measures and resilience-building strategies will secure a sustainable future for generations, ensuring global environmental justice that respects every community and culture on our planet.”

Daniel Ofman reported [[link removed]] from Lviv, Ukraine, where students are trying to imagine a postwar future. Some students in Lviv are at home while their parents serve in the military. Others have lost loved ones. Still others are internally displaced, having moved to Lviv after the outbreak of Russia’s all-out war on their country. Ofman also found that, though the war does come up in conversation, many want to avoid the subject, determined as they are to have some sense of normalcy — though, as Ofman pointed out, boys in particular have to think about it given that military service looms over them.

Aya Asakura and Patrick Winn wrote [[link removed]] about the Japanese government’s new role in young people’s lives: matchmaker. Almost a third of Japanese people under 40 have never been in a relationship. Sociologists warn that the country is entering a “marriage ice age,” and leaders consider this to be a crisis. So, Asakura and Winn explained, “Most Japanese prefecture-level governments now offer ‘marriage support,’ usually online-based systems that pair singles looking for romance.” They spoke to officials from Saitama prefecture to learn more about how the whole process works, and found that it involves a selfie, proof of income, and an extensive personality quiz. And unlike online apps, the prefecture won’t let you chat before the date. They are trying to arrange marriages, too — those looking for something more casual should probably look to a site that isn’t run by the government.

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] WELL-PLAYED

Pup-idential immunity [[link removed]].

Took a sad game and made it better [[link removed]].

Everything must go [[link removed]]!

Zut alors [[link removed]]!

They can’t keep getting away with this [[link removed]].

Something nice [[link removed]].

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] Follow The World: DONATE TO THE WORLD [[link removed]] Follow Inkstick: DONATE TO INKSTICK [[link removed]]

Critical State is written by Emily Tamkin with Inkstick Media.

The World is a weekday public radio show and podcast on global issues, news and insights from PRX and GBH.

With an online magazine and podcast featuring a diversity of expert voices, Inkstick Media is “foreign policy for the rest of us.”

Critical State is made possible in part by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Preferences [link removed] | Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed]

read about Paris before the Olympics!

In New Lines, Dalal Mawad offers a dispatch [[link removed]] from Paris before the Olympics — and it’s one about the repression of sex workers.

Sex work is not illegal in France: “In 2016, the country replicated what is known as the Nordic model for sex work, decriminalizing public solicitation of sexual services and punishing only the client who pays for sex. In the eyes of the law, the women are all victims and cannot be punished.”

However, most sex workers are undocumented migrants, and various NGOs shared that documentation control has increased. “These controls are being used to go after the women because the police cannot criminalize them as sex workers, only as undocumented foreigners,” Mawad explains.

This has meant that sex workers are not reporting cases of abuse by clients — like rape — to the police. They have also appeared less at NGOs that might provide support. As Mawad puts it, “They have become less visible and therefore more vulnerable.” And many fear that, given the rise of the country’s xenophobic far right, which performed well in the first round of the early parliamentary elections called by French President Emmanuel Macron, the crackdown won’t end with the Olympics.

Life Is But a Dream

In Noema, writer and musician Claire L. Evans looks at [[link removed]] lucid dreams, exploring the idea that consciousness is really on a spectrum between sleep and waking.

More than half of adults will experience a lucid dream at some point: “They’ll go to sleep, and as their REM cycles accumulate, as night shades into morning, as their sports car turns into a banana, they will suddenly realize, as I did: This is not real. This is a dream.” Evans also explains that lucid dreams are as old as the mind. “They’ve long been central to the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition, which teaches the cultivation of conscious awareness even in deep sleep. In the West, the philosophical literature of lucidity reaches back to Aristotle,” Evans writes. But modern science left them largely unexamined until well into the 20th century.

Now that there has been some research, we know that lucid dreams tell us something about consciousness. As Evans writes, “Dreaming and waking perception are both illusory; they’re models constructed by our brains that turn sensory stimulus, or its absence, into meaning. In waking life, short of a heavy psychedelic experience, that illusion is all-encompassing; there’s no other level of consciousness to ‘wake up’ into.” In lucid dreams, however, “we can examine the construction closely.”

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] Unerased

Nick Holdstock writes [[link removed]] for The Dial on two recent Uyghur memoirs that grapple with writing about an oppressed minority in such a way that they are not only an oppressed minority.

As Holdstock explains, these memoirs come at a particular time: “The last decade has been the darkest period in Uyghur history since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Over 1 million Uyghurs and other Muslims have been interned in ‘reeducation’ camps in the Xinjiang region of China since 2017. Mosques have been demolished, artists and intellectuals detained, and Arabic writing removed from many shops and signs. There have been forced sterilizations of Uyghur women and forced marriages between Uyghurs and Han Chinese.” Every element of Uyghur culture is treated as suspect.

Holdstock considers Gulchehra Hoja’s “A Stone Is Most Precious Where It Belongs” and Tahir Hamut Izgil’s “Waiting To be Arrested at Night,” both of which, per Holdstock, raise questions of “How can a writer fashion their individual story, and the larger story of their people, in a way that generates interest and sympathy? What kinds of thoughts and feelings does such fashioning facilitate — and what might it suppress?”

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] DEEP DIVE Militant Democracy?

If European Union member states are backsliding democratically, should the EU respond with “militant democracy”? Is it already doing so?

Those are the questions before Tom Theuns in the paper [[link removed]] “Is the European Union a militant democracy? Democratic backsliding and EU disintegration” published by Cambridge University Press.

Theuns argues that the EU is a militant democracy in a limited, specific sense, but that this might actually be counterproductive for democratic purposes.

Theuns argued that the strongest argument for militant democracy requires two conditions be met: “an ‘existential threat condition’ and a ‘necessity condition.’” The existential threat condition says that if the threat does not existentially threaten the polity as a democracy, a militant democratic response is not justified.

For example, “When faced with minor threats, democracies should wield the standard tools of criminal and constitutional prohibitions, sanctioning anti-democratic actions with fines or imprisonment rather than targeting the equal civil and political rights of anti-democratic actors.” Relatedly, the necessity condition means that militant democratic measures can only be used if they are necessary to “neutralize” the threat.

Theuns writes that, to be a militant democratic measure in a narrow sense, that measure must “be suitable to responding to existential threats to the democratic character of the European Union” and also “sanction anti-democratic actors by limiting their equal civil or political rights rather than via ordinary and generalized sanctions proscribing anti-democratic actions.”

He then analyzed four ways that the European Union has been alleged to be “empowered to act in a militant democratic fashion to combat democratic backsliding in EU member states”: infringement procedures; the rule of law conditionality regulation; deregistering anti-European parties and foundations; and Article 7. Theuns explains that though some of these could be described as “militant democracy,” not all could. For example, “infringement actions target the anti-democratic action through ordinary sanctions rather than targeting the equal civil and political rights of the anti-democratic actor,” which is to say they would not meet the narrow definition. On the other hand, deregistering actors does.

Theuns, though admitting that the EU may well be acting in democratic self-defense in using such measures, then questions whether the necessity condition can ever really be met by pointing out that a non-militant response is always possible though forms of EU disintegration, and so concludes that “EU actors should prioritize robust non-militant measures where possible while pro-democratic member states should disassociate from frankly autocratic member states where non-militant measures fail.” When non-militant measures fail, Theuns argues, the democratic members should instead disassociate from their authoritarian counterparts to keep the European Union — and themselves — democratic in nature.

LEARN MORE [[link removed]]

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] SHOW US THE RECEIPTS

Carla Montilla argued [[link removed]] that the climate crisis has already arrived. Montilla reminded readers that people all around the world are already feeling the various impacts of climate change. Montilla looked in particular at South Sudan and Fairbanks, Alaska, to make the case that the United States needs to do more to help tackle climate change, writing, “Investing in proactive measures and resilience-building strategies will secure a sustainable future for generations, ensuring global environmental justice that respects every community and culture on our planet.”

Daniel Ofman reported [[link removed]] from Lviv, Ukraine, where students are trying to imagine a postwar future. Some students in Lviv are at home while their parents serve in the military. Others have lost loved ones. Still others are internally displaced, having moved to Lviv after the outbreak of Russia’s all-out war on their country. Ofman also found that, though the war does come up in conversation, many want to avoid the subject, determined as they are to have some sense of normalcy — though, as Ofman pointed out, boys in particular have to think about it given that military service looms over them.

Aya Asakura and Patrick Winn wrote [[link removed]] about the Japanese government’s new role in young people’s lives: matchmaker. Almost a third of Japanese people under 40 have never been in a relationship. Sociologists warn that the country is entering a “marriage ice age,” and leaders consider this to be a crisis. So, Asakura and Winn explained, “Most Japanese prefecture-level governments now offer ‘marriage support,’ usually online-based systems that pair singles looking for romance.” They spoke to officials from Saitama prefecture to learn more about how the whole process works, and found that it involves a selfie, proof of income, and an extensive personality quiz. And unlike online apps, the prefecture won’t let you chat before the date. They are trying to arrange marriages, too — those looking for something more casual should probably look to a site that isn’t run by the government.

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] WELL-PLAYED

Pup-idential immunity [[link removed]].

Took a sad game and made it better [[link removed]].

Everything must go [[link removed]]!

Zut alors [[link removed]]!

They can’t keep getting away with this [[link removed]].

Something nice [[link removed]].

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] Follow The World: DONATE TO THE WORLD [[link removed]] Follow Inkstick: DONATE TO INKSTICK [[link removed]]

Critical State is written by Emily Tamkin with Inkstick Media.

The World is a weekday public radio show and podcast on global issues, news and insights from PRX and GBH.

With an online magazine and podcast featuring a diversity of expert voices, Inkstick Media is “foreign policy for the rest of us.”

Critical State is made possible in part by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Preferences [link removed] | Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Public Radio International

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor