On April 16, a wave of thousands of students engulfed Avenida Mariscal López, one of the main avenues of the Paraguayan capital Asunción.

Chants of “¡Somos más de 100!” (There are more than 100 of us!) filled the evening air, giving a direct response to comments by the controversial senator Basilio Núñez that “no more than 100 people” were participating in the escalating protests against his party’s government.

The series of demonstrations, including student actions taking place across Paraguay, were set off in opposition to a new law, dubbed “Hambre Cero” (Zero Hunger), which the government says will universalize access to schooltime meals for children—a claim disputed by students.

The law also drastically alters the funding structure for numerous vital state social programs, including an exemption from fees at state universities for students from state secondary schools. The student movement states that the change puts these programs in danger.

“We demand a guarantee for all the projects that are being defunded, including free tuition,” said María Victoria Méndez, a student from the National University of Asunción (UNA), while standing by a cordon of hundreds of police blocking the march from reaching the nearby presidential residence Mburuvicha Róga.

Students protest in Asunción on April 16. (William Costa)

Paraguay has the lowest level of public spending on education in South America: just 3.6 percent of GDP. The tuition fees exemption scheme, known as Arancel Cero (Zero fees), provides essential support to approximately 60,000 students from poorer backgrounds.

The protests are positioning students as a key point of resistance against increasingly heavy-handed measures by the right-wing government of President Santiago Peña, which are progressively eating away at the rights of numerous social sectors.

“The government has displayed authoritarianism, and a total failure to listen to the criticisms of students, who are an extremely important segment of society,” said Ernesto Ojeda, another UNA student.

The focal point of the protests has been an occupation of UNA, Paraguay’s biggest university, which saw students take control of their campus for almost three weeks, suspending classes and controlling access to institutions. This determined strategy exerted heavy pressure on the government and forced it into talks.

“When UNA is on strike, and when UNA’s students protest, people take notice, and people join the cause,” said Méndez, pointing to the campesinos, members of social organizations, and Asunción residents that had come out to support the demonstration.

The Occupation

The evening after the march, there was a calmer atmosphere on the grounds of UNA’s Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences (FACEN), beyond several of the numerous student barricades controlling the sprawling occupied campus.

The faculty’s astronomical club had set up telescopes for observing the moon, while a group prepared and shared out hot mbeju—a cassava starch flat cake. Students had been running educational and recreational activities to keep up morale in the difficult conditions of the occupation. Many students were putting in sustained, intense efforts as part of teams charged with security, food, research, and infrastructure.

“There have been tough situations. I’ve cried, I’ve been extremely tired. But seeing all my fellow students here gives me strength,” reflected student Sofía Ruiz Díaz while gazing over the railing of a pond where caimans lounged.

Students have been opposing the controversial new Zero Hunger law since it was announced in January. To free up funds for the school meals policy, the law eliminated the National Fund for Public Investment and Development (FONACIDE)—drawn from proceeds of the enormous Itaipu Hydroelectric Dam. FONACIDE has hitherto been used to fund the Zero Fees scheme and programs such as funds for academic research, scholarships, and medicine for cancer patients.

Students occupied the vice-chancellor’s office at the National University of Asunción. They kept guard day and night outside the entrance and covered the building with protest posters. (William Costa)

The affected programs will now be funded using public treasury money derived from taxes. Despite repeated assurance from officials, students say that this source of funding is greatly unreliable due to Paraguay’s extremely low tax revenue and high levels of corruption. Previous social schemes funded in this fashion, such as provisions for communal kitchens, have failed to receive stipulated funds.

“There was a lot of misinformation,” said Ruiz Díaz, stating that it is was a challenge to explain the worrying situation to the student body. “We were holding assemblies, making flyers, everything to get the information across.”

Their efforts worked. On April 4, the day the law was approved in the senate, students voted in assemblies to escalate from street protests to an occupation of their institutions. Over the following days, students from 13 of UNA’s 14 faculties declared themselves on strike and joined the occupation. Students with a broad range of political ideologies were present. President Peña enacted the law on April 5.

“At first, we felt like there were only a few of us,” said student Florencia Cabañas regarding the occupation of the UNA’s FACEN. “It was incredible when 300 of our classmates showed up.”

University occupations are a tactic that have successfully been deployed at UNA in the past. Lucio Salazar, a student at FACEN, recalled his experiences participating in the last mass occupation of the UNA in 2015, which culminated in the resignation of the vice-chancellor.

Education in Paraguay

The following day, the well-organized student security team maintained the barricades and checkpoints. They chatted and played UNO while monitoring a walkie-talkie phone application that kept them updated on campus happenings.

It was not just UNA students on the barricades: students had come from other public universities across Paraguay to form part of the occupation.

Students at one of the multiple barricades set up across the campus during the occupation to control access. (William Costa)

“We took action because so many of our classmates were saying that if Zero Fees is taken away, they are simply going to stop studying as they won’t be able to pay,” said Alicia Alfonso from the National University of Caaguazú in the small town of Choré. “Zero Fees is extremely important: effectively 99.9 percent of students in Choré depend on it.”

Alfonso said that since Zero Fees was implemented in 2021, following a hard-fought student campaign during the pandemic, more people were accessing the university in Choré, especially from campesino families.

A group of students guarding the vice-chancellor’s office, which was also under occupation and plastered with placards, explained just how difficult it was, even with the help of Zero Fees, for many youths to make it through their studies. Almost half of the student population studies and works full time, many receiving less than minimum wage. This is one of the main reasons that only around 10 percent of students that enroll graduate.

“What I earn just about covers my needs. If I have to pay university fees, I’m not going to be able to study,” said UNA student Ricardo Guerrero, a beneficiary of Zero Fees who also holds down a job. “So many other students are in the same situation.”

Notably, many students said they had been eating better during the occupation than in their normal daily life; donations from the general public were allowing them to prepare regular communal meals.

Students with more stable economic backgrounds were also participating in the protests: many said the occupation had opened their eyes to the dire situation of their course mates. Others commented that the occupation was providing a political “crash course” on social activism.

“The government is manipulative and has made it seem as if we were the ones wanting to take food from the children. However, we want to guarantee them just that: good food and a good future,” said the students outside the vice-chancellor’s office in reference to the “Zero Hunger” program that authorities say will reduce hunger in schools.

They criticized the very low budget allocated for the program, which will only provide one meal a day per child. Education minister Luis Ramírez justified this by pointing to the apparent benefits of "intermittent fasting."

There are also concerns about minister for social development Tadeo Rojas, who will oversee the program’s funds; Rojas has faced serious corruption accusations.

Increasing Authoritarianism

The experience of the majority of students starkly contrasts with a series of recent nepotism scandals in congress. Numerous unqualified children and relatives of members of Peña’s government, the latest in 80 years of almost uninterrupted rule from the far-right Colorado Party, have been revealed to be working for high salaries in public institutions.

This includes the unqualified daughter of Yamil Esgaib, a Colorado congressman who publicly labeled student protestors as “ignorant”.

Protest posters at the National University of Asunción’s Faculty of Architecture, Design and Art. (William Costa)

“Unfortunately, it’s a government characterized by corruption, by looking after the interests of a few at the cost of the rest of us,” said one of the students outside the vice-chancellor’s office.

Indeed, Paraguay has the second-highest corruption perception ranking in South America and appears fourth on the Global Organized Crime Index.

Since Peña took office in August 2023, his government has abused a majority in congress to expel a strongly critical opposition senator, violently implemented actions affecting pensioners and workers, and coopted the justice system to protect its own interests, especially those of former president Horacio Cartes, who is widely said to be the true powerholder behind his protégé Peña.

Students have shown themselves capable of resisting the steamroller of the Colorado government, managing to strengthen links with other social sectors, such as unions, pensioners, and university teaching staff and researchers.

“They underestimated the student movement,” said economics student Óscar Palavecino, sipping mate as a cold evening set in on campus, and recalling Peña’s comments that students were just a “noisy minority.”

Students showed apprehension about possible repercussions for the protests. For example, Vivian Genes, one of the main student leaders behind the 2020/21 Zero Fees campaign, was criminalized and currently faces prosecution in court.

As such, students were taking security on campus extremely seriously. They said that plainclothes police had repeatedly tried to illegally enter the campus and had trailed student activists on the streets.

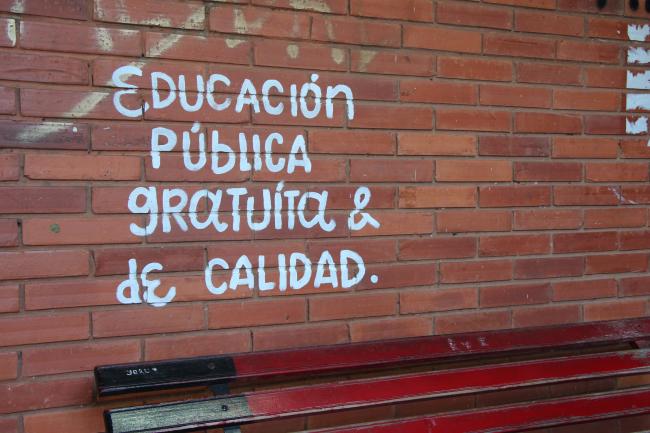

“Free and good quality public education” on the wall at the National University of Asunción’s Faculty of Architecture, Design and Art. (William Costa)

Students and Workers

The occupation of UNA gradually came to an end in the days after April 19, when a meeting between student leaders and government officials took place. A document was signed committing the parties to participate in talks to move discussions forward.

This did not mark the end of the student movement’s struggle; they continue to exert pressure. On May 1, for example, students took to the streets for an International Worker’s march in central Asunción alongside unions and social organizations.

Ana Florentín, a medical student, said that physical and psychological fatigue, alongside the pressing need to continue with their studies, had contributed to the decision to end the occupation.

“It was mainly because we need to move on to another form of protest. We need to coordinate with other organizations, like the workers here today,” she said as chants of “Workers and students, united in struggle!” went up from the crowd.

Students marched alongside union workers and social organizations on International Workers' Day on May 1. (William Costa)

Florentín emphasized that students are ready to occupy UNA again if necessary.

Hugo Mendieta, who had just finished his studies at UNA, said that students did not trust the government and that Peña had already shown signs of dishonoring the agreement. The student movement, however, had emerged from the occupation unified and strengthened.

“Students are motivated to continue taking actions to oppose the government,” he said. “This is what those in power fear: students organizing alongside unions and social organizations. I think it’s possible for us to form a large alliance across Paraguay.”

Florentín underscored that the student struggle was not solely about Zero Fees, but was an effort to defend the interests of all groups affected by the changes brought about by the Zero Hunger law.

“The government is taking funds away from vulnerable groups because it thinks those groups won’t protest,” she said. “We students cannot remain silent faced with that injustice and we will keep going until we achieve our goal.”

The first round of talks between students and representatives of the government took place on May 9 and are set to continue.

William Costa is a freelance journalist based in Asunción, Paraguay. He concentrates on social, environmental, and cultural topics.

The North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) is an independent, nonprofit organization founded in 1966 to examine and critique U.S. imperialism and political, economic, and military intervention in the Western hemisphere. In an evolving political and media landscape, we continue to work toward a world in which the nations and peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean are free from oppression, injustice, and economic and political subordination.

As the Americas stand at a crossroads, NACLA's research and analysis remains as important as ever. Can we count on your to support our work?

DONATE NOW!