|

The Four Pathways to Constitutional Rights for Animals

Ordinary people have the power to change the most fundamental laws of a nation. Here's how.

The constitution shapes the decisions of everyone in a nation, from ordinary citizens to presidents and even kings. That makes the constitution vital for anyone interested in making change. To solve a problem as large and multifaceted as violence against animals, constitutional change may be the only answer.

But how do we create constitutional change? The surprising answer, based on the lessons of history, is that constitutional change doesn’t depend on words written on pieces of paper, or old men in robes. Rather, constitutional change depends on a mass political movement made up of ordinary people. And while that movement has a number of pathways it must fill – not just legal but also narrative, political, and community – if those pathways are filled, constitutional change for animals isn’t just likely but inevitable.

We can see this by understanding how the US Constitution changed for me.

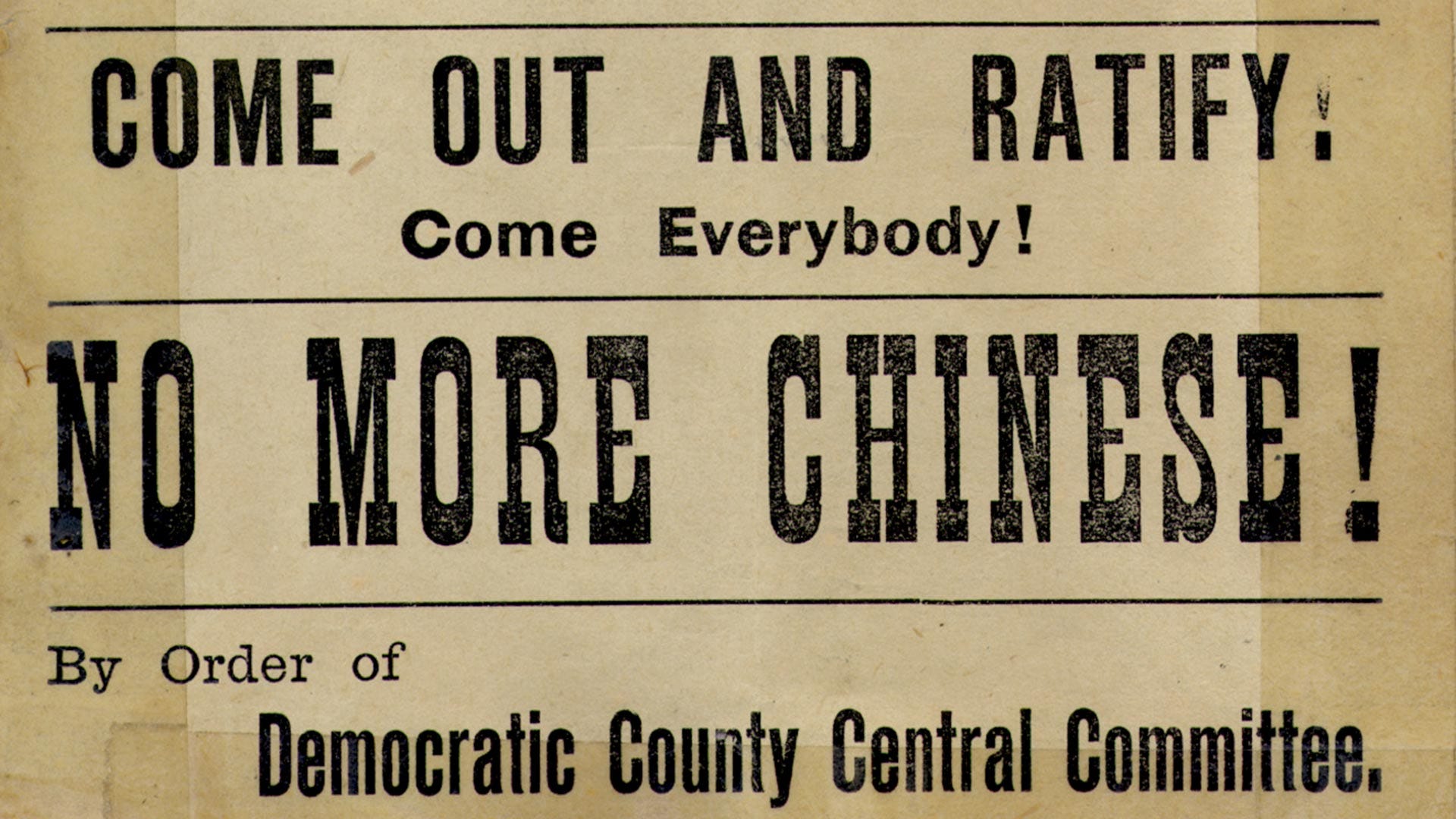

My presence in this country is a minor miracle. In 1882, 14 years after the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution gave all “persons” the “equal protection of the laws” regardless of their race, the United States Congress passed its first-and-only race-based exclusion law in history: the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The law banned all immigration of Chinese people into this country, and denied permanent residents who were Chinese the right to become citizens. Bizarrely, there appears to have been little discussion of how this racism was consistent with the Fourteenth Amendment’s “equal protection” clause.¹ (Criticism of the law focused instead on whether it complied with American treaty obligations.) It was not until Congress repealed race-based preferences in immigration in 1965 that Chinese people began coming to the US in significant numbers. My parents were part of this first wave of Chinese immigrants in the early 1970s. My existence in this country is a result of that lucky timing.

Today, the Chinese Exclusion Act is widely understood as one of the most deplorable and unconstitutional instances of racial discrimination in American history. Yet for nearly a century, no one was able to effectively challenge it. What changed in the 1960s?

The answer is not any change to the text of the Constitution. The equal protection clause existed in exactly the same form both before and after 1965.

The answer also does not lie with old men in robes. To the contrary, judges and lawyers had ruled for many decades that racial discrimination was somehow consistent with “equal protection.” Even when courts finally took small steps to remedy this hypocrisy in the 1950s, it had little impact, as state governments ignored court orders to end racist policies.

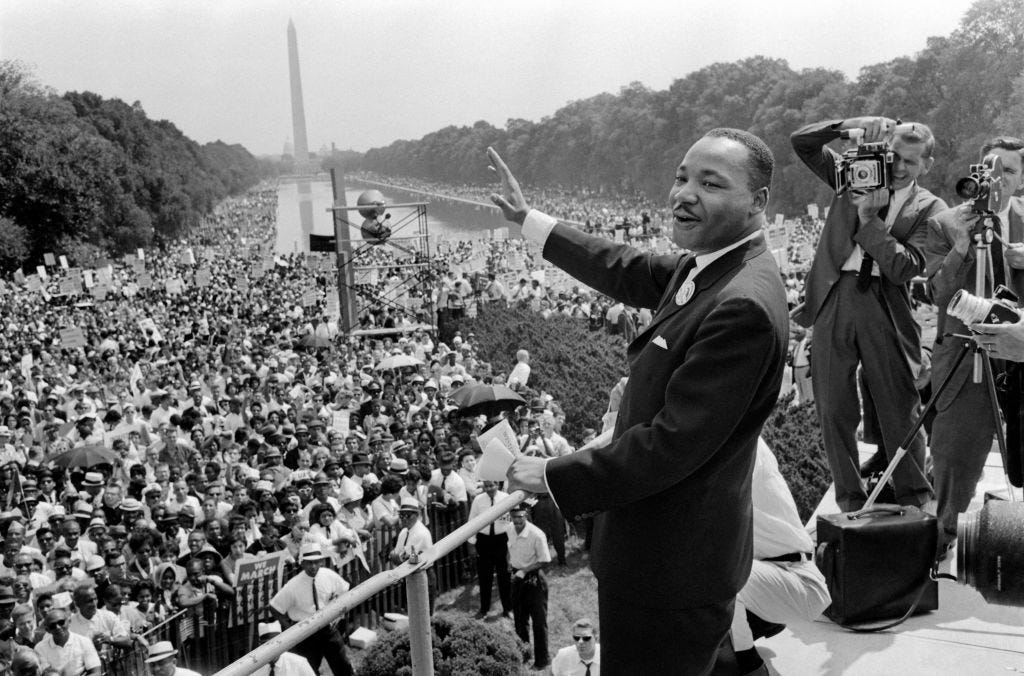

The answer to how constitutional change actually happened lies in the mass political movements of the 1960s, including the Civil Rights and Anti-Vietnam War movements. Activists in these movements reshaped the constitutional meaning of “equal protection” and enshrined a new and correct understanding of those words in the social and political fabric of the nation. And they used four important pathways to do so.

The first pathway was narrative. Prior to the movements of the 1960s, the United States government told a story of a righteous nation protecting democracy and freedom from the threat of communism; this story was mostly accepted through the 1950s. But Martin Luther King, Jr. and other activists had a different narrative: the story of a constitution whose promise had been broken. As King said at the March on Washington in 1963:

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir… It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned.

King’s constitutional arguments were the biggest story in the nation, making the front page of The New York Times. But there were other examples of transformative storytelling, including Harper Lee’s 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird. That novel, the story of a Black man falsely accused of rape, became a national sensation and exposed millions of Americans to the plight of people of color. It was even turned into a movie which won Gregory Peck an Academy Award in 1962. It was these powerful narratives, and not the words written by judges, that ultimately reshaped the nation’s story of “equal protection.”

Storytelling alone was not enough, however. The stories told by activists needed to be embedded in the governing structures of the nation. That is why the second pathway for constitutional change was political, culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. That Act created an entire system of enforcement that gave life to the words “equal protection” in a way that no judge, acting without political support, ever could. And it was not lawyers but activists who led the charge in this political fight. The Civil Rights Act was the direct result of local political victories in places like Montgomery, the site of Rosa Parks’ infamous arrest in 1955, and Birmingham, where King organized a successful direct action campaign in 1963. Constitutional change was achieved through this development of political power.

Political power, however, could only be developed through community, the third pathway to constitutional change. The Black churches in Montgomery convinced 90% of the Black population of the city to join King’s direct action campaign. (By way of comparison, at most 200 local vegans joined our mass open rescue at Sunrise Farms in 2018, or around 0.3% of the Bay Area vegan community.) Community organizers created conferences, such as a summit at Shaw University in 1960 that launched the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the careers of a half dozen legendary civil rights leaders including John Lewis, Diane Nash, and Julian Bond. This community organizing reached its peak when 200,000+ marched on Washington in 1963, showing both politicians and the public that a significant and growing portion of America’s community supported equal protection for all races. Political efforts that were fringe just a decade earlier suddenly had immense momentum due to this community.

Then, finally, there was the legal pathway. Legal cases, such as Rosa Parks’ arrest in Montgomery, or King’s own incarceration in Birmingham, became flash points in the movement for equal protection. But it’s crucial to note that these legal trials were used as vehicles for a broader constitutional campaign, and not as the primary vehicles for constitutional change. Very few people recall that Rosa Parks “lost” her criminal case; the arguments made by her lawyers in court have been mostly forgotten. And the most important constitutional argument in King’s criminal case in Birmingham was not one made in court, but in the letter he penned from a Birmingham jail. The moral of the story is that, while court cases are crucial to creating constitutional change, it is often ordinary people - and not lawyers or judges - who make the most important arguments. The legal pathway, in other words, is powerful mostly because it empowers the other pathways for change.

My family members – and millions of other people of color – were the beneficiaries of the movement that realized the power of these four pathways. And these pathways were not just important for civil rights but for other great movements through American history.²

But can we harness these pathways to create constitutional change for animals? The answer is yes! We know this not just because of the lessons of history but because these pathways are already being used. From political efforts to ban factory farms in Sonoma County to narratives pushed out into the mainstream media, change is in the air. Now, we just need a clear, long-term vision and strategy integrating the work that is being done towards common goals.

It’s for this reason that, for the first time, we are releasing a preliminary roadmap for you and others to read, comment on, and take part in. The roadmap has four milestones set for each pathway by the year 2050:

Legal: Supreme Court recognizes animals are sentient beings entitled to be rescued from violence

Narrative: Right to Rescue movement is known — and supported — by bipartisan majority of Americans

Political: US Congress passes major legislation in defense of the right to rescue

Community: Annual right to rescue summit attracts 100,000 attendees

The roadmap also sets out the precise steps that must be taken, starting in the next year, to achieve these milestones by 2050.

When you read the roadmap, and compare it to the historical events I discuss above, ask yourself two questions:

Does this seem possible for animal rights?

Does this seem like something that you can help with?

There is much more I could say. For example, why is rescue central to this roadmap? And how does it relate to the prior roadmap we released at Direct Action Everywhere in 2016? The truth is that I don’t have all the answers. And that is precisely why we’re releasing this roadmap and calling it version 0.1. We need feedback from you! But while we do not yet have the answers, I think our movement is starting to ask the right questions. And if we ask and answer these questions together – tapping into the passion and knowledge of advocates across the globe – we will achieve our constitutional vision: a world where every animal has the right to live safe, happy, and free.

If you’re interested in hearing more about this subject, we’ll be hosting a discussion on Saturday, May 25 at 1:30 pm – both in person in San Francisco and on Zoom – at which I’ll be sharing more about the roadmap and seeking your feedback and involvement. RSVP here. I hope to see you then and there.

What’s up this week?

Animals have been in the news this week, from the puppy-killing ways of a prominent Republican Vice Presidential contender to the Florida ban on cultured meat. It’s encouraging to see some of the most prominent voices in the media, including Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman, offer (implicit) support for animal rights. But the most disturbing news is the rapid spread, and mutation, of a deadly form of avian flu. We made a video about what’s happening:

I’ll be at the Animals and Vegan Advocacy Summit in Washington, DC next week to discuss the right to rescue, and the roadmap we’re releasing today. While my main talk will be at 2 pm on Saturday, May 18, I’m actually much more interested in meeting up with activists informally - to hear what you’re most interested in, and to get you plugged in. For that reason, we’re organizing a series of informal meetings every evening of the conference for those of you interested in being a part of the movement for the right to rescue. See here for more details and to RSVP for the nightly meetings.

We have some news we’re releasing on Friday - the first step in a bigger ecosystem around activism and rescue. Stay tuned for more. I’ll be sending out an email to share what’s up!

While the Fourteenth Amendment’s text only applies to state government, it also applies to the federal government through the doctrine of reverse incorporation.

Narratives such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin allowed the antislavery movement to not just reach, but persuade, millions of Americans. Political campaigns, such as California’s Proposition 4 in 1911, were the crucial building blocks upon which women’s suffrage turned into a successful national amendment in 1920. Community centers such as Lesbian and Gay Center in NYC, where playwright Larry Kramer gave a fiery speech in 1987 that launched ACT UP, were the fertile ground for the gay rights movement’s success three decades later in the Supreme Court. And, finally, legal battles, from the trial of Susan B. Anthony to the prosecution of Rosa Parks, fueled all other efforts – narrative, political, and community – by using dramatic individual cases to illustrate the need for systemic change.

Thank you for reading The Simple Heart! To help us reach more people, become a donor today.