Email

NEW REPORT: Why states should stop excluding violent offenses from criminal justice reforms

| From | Peter Wagner <[email protected]> |

| Subject | NEW REPORT: Why states should stop excluding violent offenses from criminal justice reforms |

| Date | April 7, 2020 3:41 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Plus: An interactive state map

Prison Policy Initiative updates for April 7, 2020 Showing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

New report, Reforms Without Results, lays out the case for including people convicted of violence in criminal justice reforms [[link removed]]

As the threat of a COVID-19 disaster in U.S. prisons looms, people serving time for violent crimes may be most at risk, as states like California [[link removed]] and Georgia [[link removed]] exclude them from opportunities for rapid release. "Violent offenders" — even those who are old and frail — are being categorically denied protection in a pandemic.

Letting people convicted of violence apply for life-saving opportunities requires political courage, just as it has for decades. But denying relief to people based exclusively on their crime of conviction is as ineffective as it is unjust. In a new report, Reforms Without Results, [[link removed]] we review the existing research on violent crime, explaining six major reasons why states should include people convicted of violence in criminal justice reforms:

Long sentences do not deter violent crime. Most victims of violence, when asked, say they prefer holding people accountable through means other than prison, such as rehabilitative programs. People convicted of violent offenses have among the lowest rates of recidivism — belying the notion that they are "inherently" violent and a threat to public safety. People who commit violent crimes are often themselves victims of violence, and carry trauma that a prison sentence does nothing to address. People age out of violence, so decades-long sentences are not necessary for public safety. The health of a person's community dramatically impacts their likelihood of eventually committing a violent crime — and community well-being can be improved through social investments rather than incarceration.

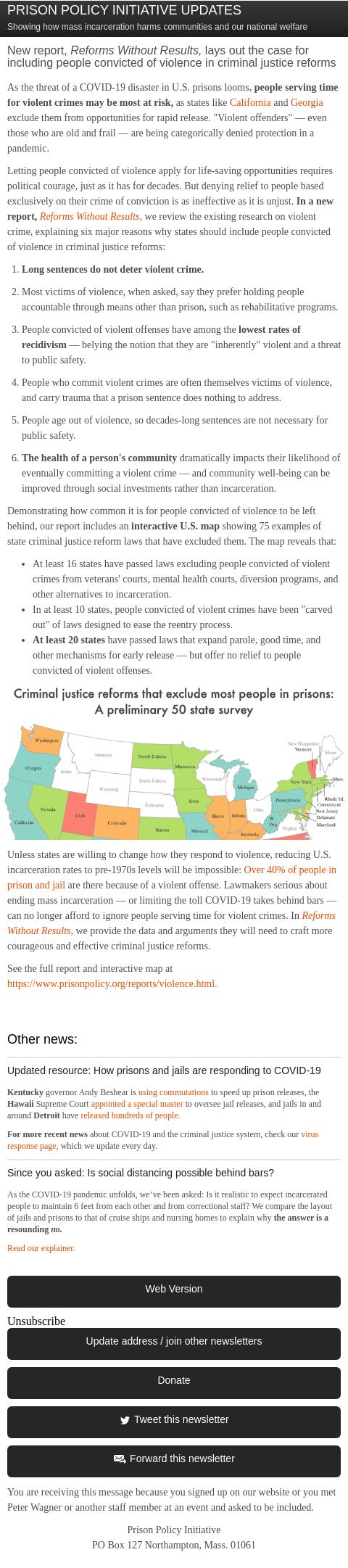

Demonstrating how common it is for people convicted of violence to be left behind, our report includes an interactive U.S. map showing 75 examples of state criminal justice reform laws that have excluded them. The map reveals that:

At least 16 states have passed laws excluding people convicted of violent crimes from veterans' courts, mental health courts, diversion programs, and other alternatives to incarceration. In at least 10 states, people convicted of violent crimes have been "carved out" of laws designed to ease the reentry process. At least 20 states have passed laws that expand parole, good time, and other mechanisms for early release — but offer no relief to people convicted of violent offenses.

Unless states are willing to change how they respond to violence, reducing U.S. incarceration rates to pre-1970s levels will be impossible: Over 40% of people in prison and jail [[link removed]] are there because of a violent offense. Lawmakers serious about ending mass incarceration — or limiting the toll COVID-19 takes behind bars — can no longer afford to ignore people serving time for violent crimes. In Reforms Without Results, [[link removed]] we provide the data and arguments they will need to craft more courageous and effective criminal justice reforms.

See the full report and interactive map at [link removed]. [[link removed]]

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Updated resource: How prisons and jails are responding to COVID-19 [[link removed]]

Kentucky governor Andy Beshear is using commutations [[link removed]] to speed up prison releases, the Hawaii Supreme Court appointed a special master [[link removed]] to oversee jail releases, and jails in and around Detroit have released hundreds of people. [[link removed]]

For more recent news about COVID-19 and the criminal justice system, check our virus response page, [[link removed]] which we update every day.

Since you asked: Is social distancing possible behind bars? [[link removed]]

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds, we’ve been asked: Is it realistic to expect incarcerated people to maintain 6 feet from each other and from correctional staff? We compare the layout of jails and prisons to that of cruise ships and nursing homes to explain why the answer is a resounding no.

Read our explainer. [[link removed]]

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives) [[link removed]]

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for April 7, 2020 Showing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

New report, Reforms Without Results, lays out the case for including people convicted of violence in criminal justice reforms [[link removed]]

As the threat of a COVID-19 disaster in U.S. prisons looms, people serving time for violent crimes may be most at risk, as states like California [[link removed]] and Georgia [[link removed]] exclude them from opportunities for rapid release. "Violent offenders" — even those who are old and frail — are being categorically denied protection in a pandemic.

Letting people convicted of violence apply for life-saving opportunities requires political courage, just as it has for decades. But denying relief to people based exclusively on their crime of conviction is as ineffective as it is unjust. In a new report, Reforms Without Results, [[link removed]] we review the existing research on violent crime, explaining six major reasons why states should include people convicted of violence in criminal justice reforms:

Long sentences do not deter violent crime. Most victims of violence, when asked, say they prefer holding people accountable through means other than prison, such as rehabilitative programs. People convicted of violent offenses have among the lowest rates of recidivism — belying the notion that they are "inherently" violent and a threat to public safety. People who commit violent crimes are often themselves victims of violence, and carry trauma that a prison sentence does nothing to address. People age out of violence, so decades-long sentences are not necessary for public safety. The health of a person's community dramatically impacts their likelihood of eventually committing a violent crime — and community well-being can be improved through social investments rather than incarceration.

Demonstrating how common it is for people convicted of violence to be left behind, our report includes an interactive U.S. map showing 75 examples of state criminal justice reform laws that have excluded them. The map reveals that:

At least 16 states have passed laws excluding people convicted of violent crimes from veterans' courts, mental health courts, diversion programs, and other alternatives to incarceration. In at least 10 states, people convicted of violent crimes have been "carved out" of laws designed to ease the reentry process. At least 20 states have passed laws that expand parole, good time, and other mechanisms for early release — but offer no relief to people convicted of violent offenses.

Unless states are willing to change how they respond to violence, reducing U.S. incarceration rates to pre-1970s levels will be impossible: Over 40% of people in prison and jail [[link removed]] are there because of a violent offense. Lawmakers serious about ending mass incarceration — or limiting the toll COVID-19 takes behind bars — can no longer afford to ignore people serving time for violent crimes. In Reforms Without Results, [[link removed]] we provide the data and arguments they will need to craft more courageous and effective criminal justice reforms.

See the full report and interactive map at [link removed]. [[link removed]]

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Updated resource: How prisons and jails are responding to COVID-19 [[link removed]]

Kentucky governor Andy Beshear is using commutations [[link removed]] to speed up prison releases, the Hawaii Supreme Court appointed a special master [[link removed]] to oversee jail releases, and jails in and around Detroit have released hundreds of people. [[link removed]]

For more recent news about COVID-19 and the criminal justice system, check our virus response page, [[link removed]] which we update every day.

Since you asked: Is social distancing possible behind bars? [[link removed]]

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds, we’ve been asked: Is it realistic to expect incarcerated people to maintain 6 feet from each other and from correctional staff? We compare the layout of jails and prisons to that of cruise ships and nursing homes to explain why the answer is a resounding no.

Read our explainer. [[link removed]]

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives) [[link removed]]

Update which newsletters you get [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor