|  | Know better. Do better. |  | Climate. Change.News from the ground, in a warming world |

|

| | | By Jack Graham | Climate change and nature correspondent, UK | | |

|  |

| Running dry

On the southern tip of Central America, the country of Panama has become almost synonymous with its famous canal.

Carrying ships from the Pacific to the Atlantic in just hours, the Panama Canal is a vital global trade route that has brought billions in revenue and put the small nation firmly on the geopolitical map.

But when my colleague Anastasia Moloney visited the canal, she heard how a series of droughts is disrupting canal operations.

Last year, the area around the canal had one of its two driest years in 143 years of records. The lack of rainwater has forced the canal to cut the number of ships passing through each day from 36 to 24 this year.

A container ship waits for water to fill at the Miraflores locks as it crosses through the Panama Canal, Panama. February 15, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Enea Lebrun. |

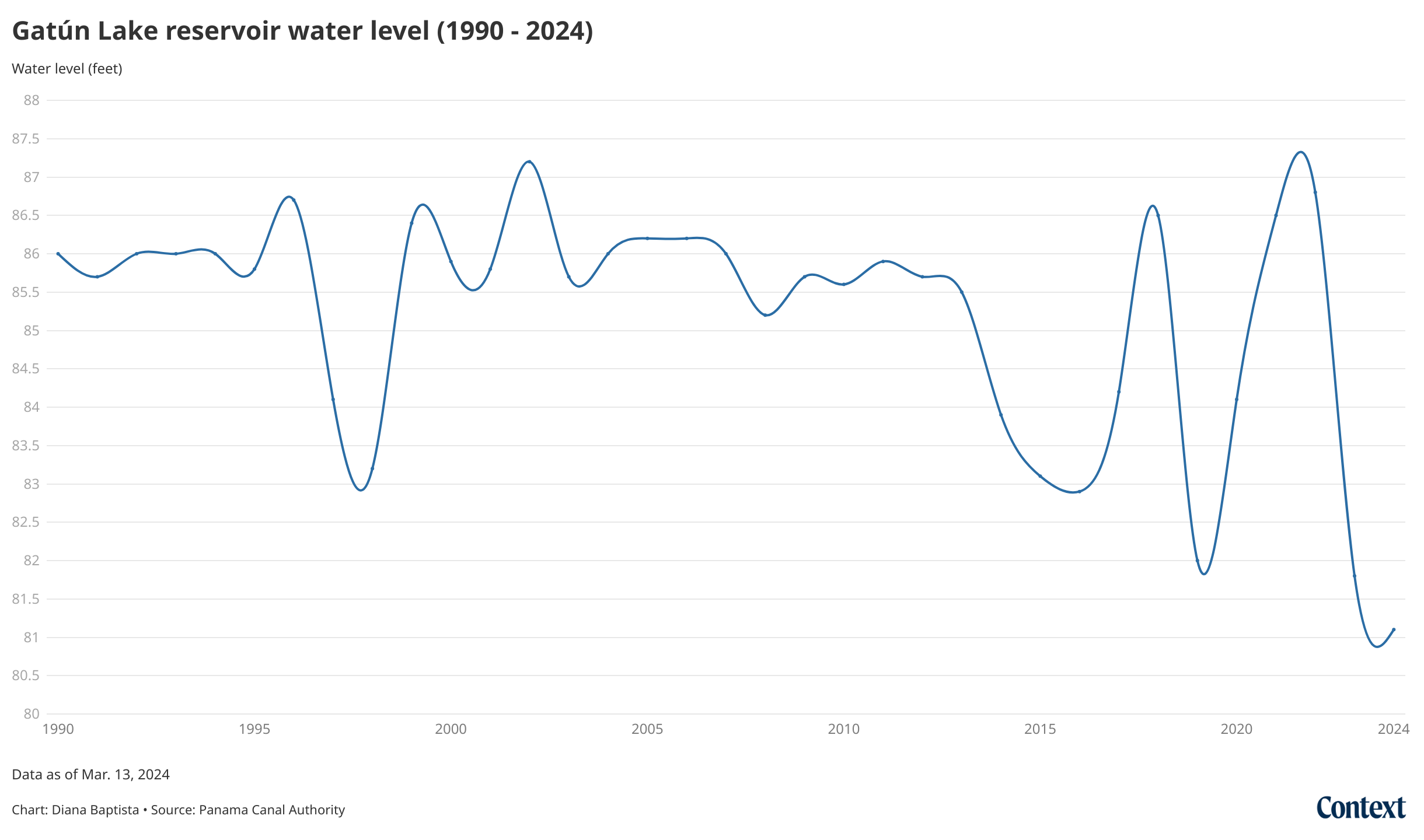

These more frequent droughts, linked to the changing climate, are also threatening access to drinking water. Gatún Lake, the main rainfall-fed reservoir that feeds the canal locks, also provides for about half of Panama's 4.5 million

people.

Balancing these demands on a finite resource will be critical for whoever comes to power after a presidential election in May. And worse could be yet to come.

"I need to be preparing for a drought in the next four years," Erick Córdoba, manager of the canal's water division, told Context.

"During the next drought, drinking water needs will surpass the water available for the transit of ships," he said. "That's the problem."

.png/640w) Thomson Reuters Foundation/Diana Baptista |

Down by the riverside

So what's the solution? Several things are being explored in the area, both to avoid more restrictions on ships and ensure access to drinking water.

One way to manage the water flow into the lake is by protecting and restoring tropical forests, which help to capture and store water. The Panama Canal Authority (ACP) is incentivising local residents to conserve the rainforests, for example.

The biggest shift needed is to find new sources of freshwater. The ACP's board has proposed creating a new reservoir on the Indio River, a two-hour drive away. The $1.2-billion project could secure canal operations and drinking water until 2075.

But 230 communities depend on that river. Many are concerned that a new reservoir would flood farms and homes, and anger is growing over the proposals.

River Indio Bajo community leader, Yaritza Marin, at the River Indio where Panama Canal authorities hope to build a new reservoir to store water needed to operate the canal locks, Panama, February 16, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Enea Lebrun. |

"We don't agree with the project," said Yaritza Marin, a River Indio Bajo community

leader. "How will having a dam affect communities like us living downstream?"

The ACP must properly consult these forest villages but, crucially, their approval is not needed for the project to go ahead. That decision rests with the government, and whoever wins the election.

Like in several countries around the world, crucial climate-related issues are hitting the ballot box. But in Panama, the lack of rain is one problem no government can resolve.

See you next week,

Jack |

|

|

| | The Philippines must urgently restore mangroves after aquaculture damage, conservationists say, as salt farm push poses new threat | The West African nation has long depended on imported rice, but farmers are trying to change that - by using a different growing technique | El Niño's dry weather has hit Indonesian rice supplies causing record price rises for consumers and crop failures for farmers | |

| |

| | | |

|