|

Why the Ridglan Prosecution Fell Apart

The vivisection industry faced a greater threat than our rescue: a growing movement for animal rights.

I was exonerated because of a death threat.

On March 8, after nearly 3 years of prosecution, the government of Wisconsin moved to dismiss felony charges against me and my co-defendants Paul Picklesimer and Eva Hamer for rescuing a blind beagle puppy from Ridglan Farms. And here’s the reasoning the government put on the record:

“What has changed are the death threats and the coming after the business that the victims [i.e., Ridglan] have now started enduring. That is the change that has precipitated this [motion to dismiss],” prosecutor Alexandra Keyes said.

This is bizarre. What sort of legal system dismisses charges against a “criminal” because of death threats made against the “victim” of a crime? But what is even more absurd is the state’s actual reason for dropping the charges. In the weeks leading up to March 8, the state moved to prevent us from presenting evidence of animal cruelty. In legal filings, it attacked our defense theories as “disturbing,” “shameful”, and even “lunacy.” But the prosecution’s over-reaction was a sign of weakness, as demonstrated by the eventual collapse of their case. And the real reason the case was dropped is this: the industry was terrified that the court was moments away from issuing a ruling that could uncover abuse of animals by some of the largest and most powerful corporations in the world - and transform the status of animal rights.

The Subpoena Hypothesis

Within our legal team, the prevailing theory as to why the prosecution’s case fell apart was a subpoena we submitted to Ridglan Farms on February 28 requesting documents on the value of the dogs. The subpoena required that Ridglan provide to us any agreements with customers regarding dogs used in experiments. (To prove felony theft, the government had to prove the dogs we rescued had a market value of at least $2,500, which could be proven, or disproven, with these customer documents.) Through backchannel sources, we knew these agreements involved some of the biggest companies in the world, including pharma giants like Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Merck.

That is a big deal. Merck has made tens of billions of dollars in profit in recent years, in part by charging $712 for a Covid drug that cost only $17.74 to produce (and which was developed through public funding). Unbeknownst to most Americans, some of those profits have come from torturing dogs.

Take, for example, Merck’s research on new rabies vaccines. There’s already a vaccine for rabies; indeed, it has existed for over 100 years. And it works very well; out of the 100+ million dogs in this nation, only 60-70 get rabies every year. But the existing vaccine is not subject to a patent, meaning anyone can use it free of charge. However, if a company like Merck were to develop a new vaccine – and convince veterinarians to sell it to patients across the nation – it could patent the drug and make billions in profits. We obtained evidence that Merck was planning to do just that. And to do so, it would test the drug by injecting rabies into dozens of Ridglan dogs, watching as most deteriorated and died, then dissecting their brains. The subpoenaed documents could have proven this disturbing plan was in the works.

Merck, however, is just the tip of the iceberg. Numerous other companies, including Pfizer and Eli Lilly, were dealing with Ridglan. And if we obtained even a single smoking gun document, that could have caused a reputational crisis that would cost the industry billions in profit. When Anthony Fauci was alleged to have funded an experiment on sand flies and a couple of puppies, it became national news.

How much worse would it have been if household names like Merck and Pfizer were found to have tortured, not just two beagles, but thousands of dogs? That was a risk that Ridglan, and the entire industry, could not bear. So it should come as no surprise that, on the very day that Ridglan may have been ordered to hand over the docs, instead the entire case was dropped.

The Personhood Hypothesis

Perhaps even more dangerous than a document, however, was the legal principle that we were on the brink of arguing (and perhaps winning) in court. In a motion filed on March 1, my co-defendant Paul Picklesimer, through brilliant lawyers at the University of Denver’s Animal Activist Defense Project (AADP) led by staff attorney Chris Carraway, argued that the dogs at Ridglan were legal “persons,” and not “things.” The ramifications of such a defense are monumental. If animals are persons, for example, there is a compelling argument that they must be immediately freed from cages because “persons” have a right to life and liberty under the 5th and 14th Amendments to the US Constitution. Perhaps for that reason, courts have given little credence to the personhood argument – much as they scoffed at arguments for the personhood of people of color (Dred Scott) or women (Susan B. Anthony) over 100 years ago.

But something is changing in the fight over animal personhood. The debate is receiving increasing and serious attention in mainstream media, and support from some of the most important legal scholars in the nation, like Harvard Law School professors Kristen Silt and Lawrence Tribe. And, for the first time in the history of open rescue, in Wisconsin we were arguing for personhood in front of a former defense attorney, Judge Mario White, and one known for his openness and curiosity. (We speculated that this might be due to his own background as a gay black man who has seen immense change in his own rights over his lifetime.) But perhaps the most interesting factor in the argument for personhood was that we identified a clear line of legal precedent in Wisconsin showing that courts had already recognized animals as more than just things.

In State v. Bauer, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals was forced to answer the question of whether law enforcement was entitled to break into someone’s home without a warrant, when they believed that an animal was suffering inside. Cases prior to Bauer suggested that this emergency exception to the search warrant requirement should apply only to cases where a “person” inside a building was in danger. The Court in Bauer ruled that animals counted as “persons” for this purpose: “It is… state policy to render aid to relatively vulnerable and helpless animals when faced with people willing or even anxious to mistreat them.”

But, as Harvard’s Kristen Stilt argued in her brief supporting our defense, this interpretation of “person” should apply as much to private citizens as law enforcement. As Prof. Stilt wrote, “It would be inconsistent with Wisconsin public policy and indeed an absurd and irrational result if preventing bodily harm to an animal was valued so highly that it could trump the right to be free from serious state intrusion such as a warrantless search – a right enshrined in the Constitution – but rejected in the contexts of [the defendants’ assertion of a right to rescue.]”

In short, Prof. Stilt argued that animals can’t be “persons” when the government wants to break down your door to help an animal – but just “things” when a private citizen is trying to do the same. “Person” can’t mean different things depending on who’s asserting a right. And, partly for this reason, I was becoming more and more optimistic that we were on the cusp of a historic victory for animal rights. We weren’t arguing for change. We were simply arguing for consistency in the law.

But there can be no argument, much less victory, if there’s no case. And the prosecution’s dismissal on March 8 undermined our standing to pursue the personhood argument. This is one of the reasons I was profoundly disappointed when the charges against us were dropped. Our ability to establish a legal principle that could save billions of animals was compromised.

The Movement Hypothesis

That brings me, however, to the third and most compelling hypothesis: that the case was dropped because of a growing movement for animal rights. While the prosecution claimed it was responding to death threats, there was something outside of court that was even more important for our case. A movement was coming together to defend the right to rescue.

This is precisely what happened in my prior Smithfield trial. One of the most important factors in our victory in that case was the diverse and unified set of voices speaking out in the defense of the piglets we rescued from a factory farm.

That same coalition was forming with even greater strength in the Ridglan trial. The array of people and platforms that have reached out to offer support – and amplify our message – has been unprecedented. And, interestingly, Ridglan itself conceded the impact of this growing movement. In response to an inquiry from a local television outlet, Ridglan made the following statement:

"In the weeks leading up to the trial, we observed the public spectacle being planned by animal research opposition groups across the country. We also recognized how this circus-like atmosphere would likely overshadow any justice that might be delivered."

This statement effectively admitted that activists across the country forced them to dismiss the case. Not through death threats but exposure. This shows how ordinary citizens have power to create legal change. When enough people make a “public spectacle,” the law evolves. It also shows us the importance of fighting on, even as the case has been dismissed. They dropped the charges precisely because they hoped the “public spectacle” would go away. It has thus become even more crucial that we ensure the “public spectacle” happens because we know the industry is under fire. We cannot allow the dismissal to change that.

Sadly, the dismissal has already interfered with our ability to make news from this case. An op-ed we pitched to one of the most important papers in the world, that was under consideration when I was a defendant, was dropped by the paper after the charges were dismissed. And a long form feature piece in The New Yorker became a shorter column after the trial was canceled. But, even without a trial, there are still dramatic stories to tell: about the coverup of misdeeds by the largest companies in the world, like Merck; about our efforts, starting this week, to pressure the government to enforce the animal cruelty laws; and, above all, about a movement rising up to save animals from torture and death.

And these are stories you are equipped to tell. The government wants the world to believe another story: that the Ridglan trial disappeared because of “death threats” against the company. But you and I know this story is not true. Heck, even Ridglan knows that’s not true; its own statement contradicted the government’s story. And we have the ability to challenge the government’s false story with the truth: the dismissal of the Ridglan charges is an attempt by the industry and government to stop the exposure of animal abuse.

If we tell this truthful story, rather than the wild fantasies being spread by the state, the battle in the court that matters most – the court of public opinion – will be won. We can identify the corporate wrongdoers. We can establish legal precedents. And we can build a movement to change the world – and save thousands of dogs.

I hope you’ll join us in doing that on Monday, March 18.

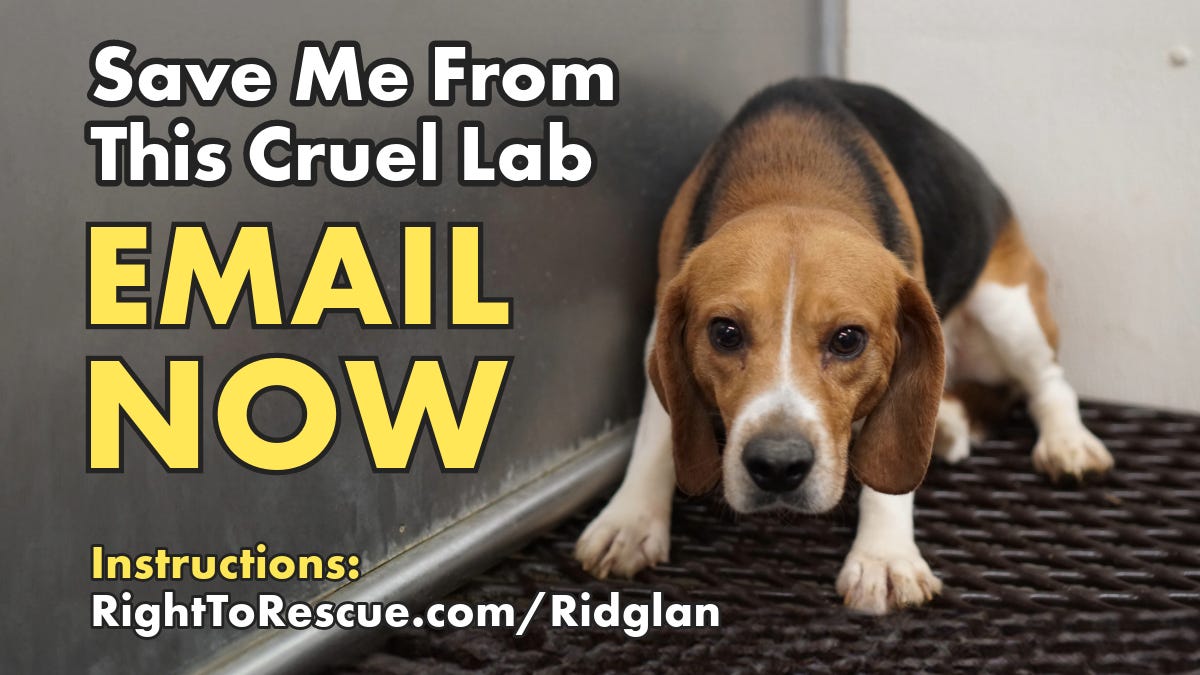

The #BeagleBetrayal day of action is here. People across the globe, including actor James Cromwell and philosopher Peter Singer, will be asking the government on March 18 to prosecute the companies that torture dogs, and not the activists who save them. Instructions are here.

The New Yorker published an important column by Jay Kang on Friday asking the question: how do we create change in a world filled with disagreement and despair? The piece is a marvelous piece of writing, and asks some of the most important questions facing those of us trying to solve the problem of animal abuse.

One of our new team members at The Simple Heart, Jeremy Loeb, published a piece in Pathways earlier this month, questioning the “sustainability” of animal agriculture. It asks the question, if we focus on “sustaining” the planet, without protecting other living beings, what are we truly sustaining?

In the leadup to the trial, I’ve done a ton of interviews with some of the most intelligent and entertaining voices in animal rights. Here are some of the interviews, which include everything from deep philosophical discussions to embarrassing dance moves.

I should be getting back to a more regular writing schedule soon. The last few months — heck, years — have been such a whirlwind, and the urgent has consistently replaced the important. But writing to, and hearing back from, all of you is one of my highest priorities in the months to come. Thanks to all of you for bearing with me. Stay tuned for more.

Thank you for reading The Simple Heart! To help us reach more people, become a donor today.