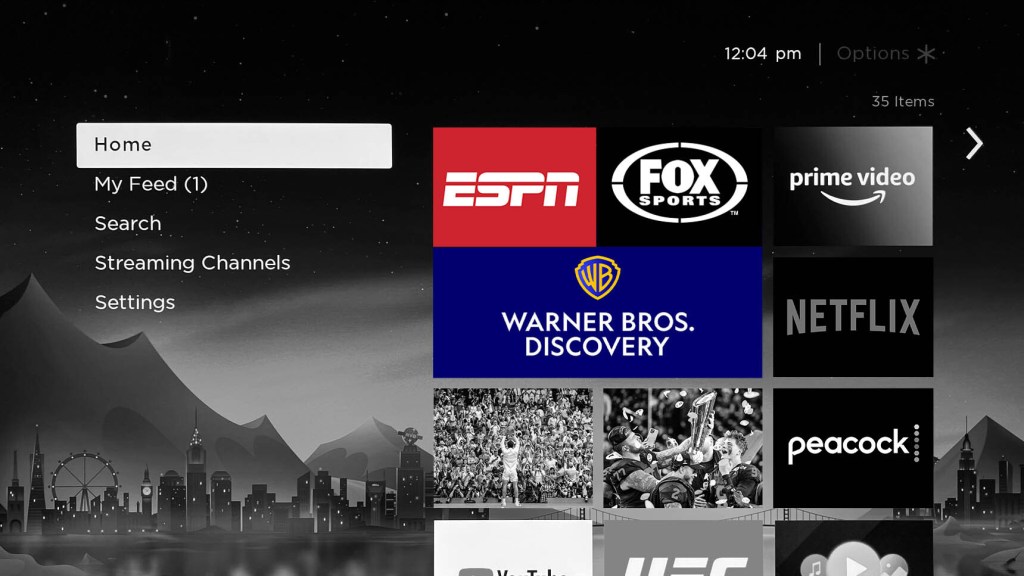

During Super Bowl week, ESPN, Fox, and Warner Bros. Discovery, three of the biggest media companies on the planet, announced a project of a scope befitting both their size and the occasion—a sports-focused streaming service one analyst called “the bundle we’ve been waiting for” and The Wall Street Journal described as a “milestone.”

The catch was that this was less a deal than an agreement to make a deal—and, other than a press release Feb. 6 about the three-headed monster (code-named “Raptor,” according to the WSJ), information has been scarce. More than a month later, with the proposed launch date of the service rapidly approaching, there is still no deal. Front Office Sports has learned the three partners in the joint venture are still working off a term sheet and have yet to sign a definitive agreement.

Meanwhile, other basic questions—who will run it and what will it be called?—appear to be mysteries not just to the public but also to the partners in the venture. They said themselves that the formation of the service was “subject to the negotiation of definitive agreements among the parties.” That negotiation is ongoing.

Here’s what we know: Scheduled to launch this fall, the new streamer will feature 14 networks and offer everything from NFL games (including ESPN’s first Super Bowls, following the 2026 and ’30 seasons), the NBA Finals, and the World Series to combat sports and a wide variety of college sports.

Due to its Cerberus-like management structure, the joint venture has been nicknamed “Hulu for Sports” or “Spulu.” Each entity will own a one-third stake and have equal board representation, and it will license its content to the service on a nonexclusive basis. (Having three owners with competing interests can, of course, sow management discord and bickering. In its early days, Hulu was nicknamed the “Clown Co.,” recalled former CEO Jason Kilar in 2012.)

Because Paramount Global’s CBS Sports and Comcast’s NBC Sports are not involved, the service is not and cannot be an all-in-one fix to the cable vs. streaming problem irritating sports fans across the country. Paramount CEO Bob Bakish perhaps predictably warned that it would offer only a “subset” of sports, including half of NFL games and little golf or soccer. “It’s hard to believe that’s ideal,” he said on an earnings call last week.

It isn’t just rivals snarking, though. Mark Shapiro, president of TKO Group, whose UFC does big pay-per-view business with ESPN+, dismissed the start-up as a “big nothing” that won’t even include ESPN’s flagship direct-to-consumer platform. “Who’s going to pay $40, $50, $60, for half the NFL package?” he asked. Topping everyone was Fox CEO Lachlan Murdoch describing the service’s subscriber projections in terms so anemic it was difficult to suss out his motives.

ESPN, Fox, and WBD declined to comment. But sources with direct knowledge of the rollout strategy, former executives from the three companies, and sports law experts expressed a clear consensus in interviews with FOS: This new venture is not close to being ready.

The most serious issue is that the deal could entirely collapse.

The three partners are still working off a nonbinding term sheet. According to a source with direct knowledge, they’re in the process of drafting definitive agreements, but it’s not a done deal yet. “Term sheets generally are not binding unless all the essential terms are agreed upon,” sports law attorney Dan Wallach tells FOS. “They’re like agreements to agree.”

A former executive with one of the companies involved—who, like other sources, was granted anonymity so they could speak candidly—warned: “They don’t even have a contract. This thing could fall apart.” A top sports media consultant who works with multiple pro teams and college conferences has been dubious from the beginning: “I’ll believe it when I see it.” Still, it’s not unusual for the various companies involved in a multiparty joint venture to take their time drafting and signing a definitive agreement. Publicly, the three partners say it’s all systems go.

All of this might be smoothed over to some extent by having a strong leader already in place, but who will be running the venture is, like its name, to be determined. That’s led to speculation the partners rushed out the news—possibly to impress Wall Street with a sexy headline before quarterly earnings calls, or to avoid a leak. (“They don’t have a contract. They don’t have a name. We don’t know who’ll run it. All they have is a press release,” says the former executive at one of the companies. “Somebody caught wind of this—and they all scrambled.”) A source with direct knowledge of the strategy says the venture is diligently “making progress” on finding a CEO who will then hire the management team. Until then, though, the project is being led on a day-to-day basis by senior leaders and technical staff from the three media companies, which is to say no one’s in charge.

Whoever ultimately takes over will have to work to mend relationships with leagues—which were indeed, sources with direct knowledge say, “blindsided” by the announcement, as the WSJ reported. Normally, leagues would bless major strategic initiatives by their TV partners, but that didn’t happen here, apart from a few cover-your-ass calls at the last minute. Commissioners don’t like being kept in the dark, and it was an “incredibly stupid move” by ESPN and WBD to blindside the NBA in the midst of their billion-dollar negotiations to retain the league’s media rights, says one NBA executive. Not seeking buy-in beforehand made the leagues suspicious. Why? Because they suspect the streaming collective is a Trojan horse, a mechanism that will allow the partners to bid for live-game rights as a combined entity rather than bid against one another. That would reduce overall rights fees, the financial lifeblood of the leagues.

NBA commissioner Adam Silver made his displeasure apparent during an appearance on ESPN’s The Pat McAfee Show. When McAfee noted he had no idea the joint venture was coming, Silver interjected, “Neither did I.” That was no slip of the tongue, says a top sports executive who knows Silver well: “Adam’s very tactical, very strategic and he’s a lawyer. He was sending them a warning shot.” The leagues may be in a snit now. But ultimately ESPN, Fox, and WBD believe the new venture will only enhance the value and reach of their content.

The value, and certainly the reach, will be determined by the answer to maybe the trickiest question of all: How much will this cost? The skinny bundle will have to come in at just the right price to attract cord-cutters and “cord-nevers.” When Fox’s Murdoch was asked at the Morgan Stanley Conference this week whether the price would range between $40 and $50, he said it would be in the “higher ranges of what people have talked about.” So figure $50 or more. That’s still cheaper than the $72.99 a month or $76.99 for comparable multichannel services, such as YouTube TV and Hulu + Live TV, but it will also offer a lot less to watch.

Looking forward, Murdoch predicted the streamer could sign five million subscribers within five years by appealing to the 60 million “cord-never” households who shun traditional cable/satellite TV. “That’s a huge market,” Murdoch said. “That’s half of the television households in this country. And we know that sports is the No. 1 driver … [of] viewership and subscriptions.” This is true—but his own prediction, if taken at face value, suggests little confidence that the nameless, leaderless entity will actually appeal to this market.

One thing that would help this appeal is launching a reliable product, rather than one that quickly develops a reputation for freezing just as your favorite team nears the goal line. Murdoch’s Fox is leading product development, but that’s a head-scratcher for skeptics because Fox has made it a point to stay out of the streaming wars. This was a smart strategy, with Fox avoiding the billions in losses suffered by competitors like Disney, but in theory it leaves it less prepared, on a technical level, than its partners. On the other hand, the Fox Sports app effectively delivered cable TV–like latency time during the network’s coverage of Super Bowl LVII in Glendale, Ariz. So Fox’s streaming chops might be underestimated.

None of this has anything to do with what might be the key issue: While all three media companies are equal partners, they are not bringing in equal amounts of revenue. This obviously has the potential to lead to disagreements over how to split the revenue generated by subscribers and advertisers. To prevent this sort of dispute, they’re playing things conservatively. Sources say the three partners will receive the same fee from streaming subscribers that they currently get from cable operators. That means ESPN, with the largest affiliate fees in cable TV at $9.42, will make more money per subscriber than Fox or WBD.

A thornier issue may be how they split advertising revenue. Will WBD, with no NFL rights, pocket some of ESPN’s Monday Night Football ad dollars? “To me, that’s the real Hail Mary,” says a former TV executive. But the source with direct knowledge of the strategy countered that the partners will separately sell and retain all of the ad revenue generated by their content. Still, how “equal” can WBD be, wondered Julia Alexander of Puck News, without NFL rights? “Why are the companies owning this equally when Disney and Fox bring the NFL and Warner [Bros.] Discovery does not?” she asked. It’s a good question without an obvious answer.

As if the above issues are not enough, the streaming newcomer will have to overcome regulatory scrutiny from the federal government, as well as lawsuits from rivals. Bloomberg recently reported the U.S. Justice Department will take a look at the new service. (The Justice Department did not return an email seeking comment. The FTC referred our call to the DOJ.) Meanwhile, FuboTV has already filed a federal lawsuit against ESPN, Fox, and WBD, charging the three companies stole “its core business idea.” Sports attorney Chris Deubert tells FOS that FuboTV’s lawsuit amounts to sour grapes. “Antitrust law protects competition. It does not protect competitors.” But FuboTV’s not giving up. Instead, CEO David Gandler describes the legal effort as a “duel to the death.”

At least one question—exactly how many streaming platforms is ESPN going to offer?—has a clear answer: Two. The current ESPN+ platform will be folded into the new venture; meanwhile, ESPN will launch a different service offering all its programming directly to the public in fall 2025.

There is a reason why in the face of all these difficulties, the partners are persisting: There is enormous potential reward here. If the super-streamer does take off, it could mark the beginning of the end for the traditional cable TV bundle and the birth of the streaming bundle—an innovation perhaps on par with Silicon Valley’s invention of the bus.

—Senior Reporter A.J. Perez contributed to this story.