| From | Front Office Sports <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Inside the Day Dartmouth Unionized |

| Date | March 9, 2024 1:03 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

March 9, 2024

Read in Browser [[link removed]]

POWERED BY

Earlier this week, I took a five-hour bus ride from New York City up to Hanover, N.H., to cover the Dartmouth men’s basketball team’s union vote. The remote Ivy League campus with a six-win basketball team wasn’t the place anyone expected to be at the forefront of athletes’ rights advocacy—but its players produced a monumental day in college sports.

— Amanda Christovich [[link removed]]

‘We Want to Be Paid’: Inside Dartmouth Men’s Basketball’s Historic Union Effort

FOS

At around 12:15 p.m. on a cold and rainy Tuesday, 11 Dartmouth men’s basketball players took a short walk together from a campus hotel to the school’s human resources office. They looked like any normal, if tall, group of college students on the way to study, grab lunch, or hang out between classes. But they were actually headed to do something quite abnormal: deal a potential death blow to NCAA amateurism.

The Big Green became the first NCAA team in history to officially join a union, voting 13–2 to become members of the Service Employees International Union’s Local 560 chapter. The Dartmouth unionization effort, which began with a petition filed in September, is one of several cases challenging the NCAA’s model that bars players from being considered employees. In February, the NLRB regional director struck down that model, ruling players are employees and have the right to hold the election.

Within minutes of the vote tally, Dartmouth’s administration filed an appeal—a process that could continue all the way up to the Supreme Court. Nothing will change for players immediately until that process concludes. But if they win the lengthy appeals process, they’ll not only get to bargain for those benefits but also set a precedent that NCAA athletes nationwide could be legally entitled to do the same. The team has already potentially opened the floodgates, however: They hope to launch an Ivy League Players Union, and they have begun fielding questions from athletes at other Division I schools and conferences who could unionize themselves.

“It’s time for the age of amateurism to end,” player representatives Cade Haskins and Romeo Myrthil, both juniors, said in a statement after the vote. They’re one step closer to making that dream a reality.

When Haskins isn’t practicing or studying, he works at the snack bar of the Dartmouth dining hall. A member of the dining hall workers union, Haskins was inspired by the collective bargaining effort that won his coworkers double the salary, extra paid time off, and other perks. He wondered whether the SEIU’s union effort might help ameliorate circumstances for his teammates.

Haskins and Myrthil, as well as the rest of the junior class, started discussing unionizing during team meals in the summer, Haskins told Front Office Sports before the vote. The group began setting up Zoom calls with the rest of the players. Ultimately, the team agreed to approach the SEIU and file a union petition with the NLRB in September.

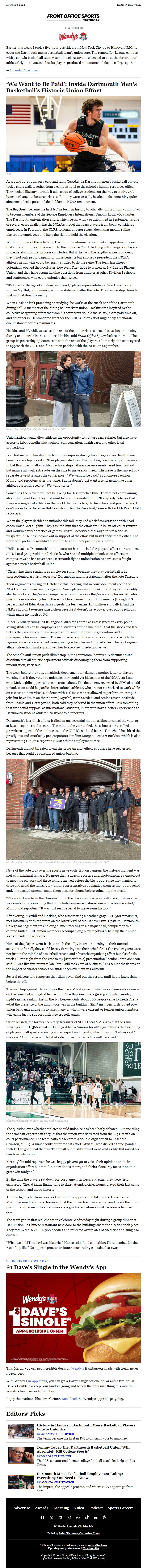

Romeo Myrthil (left) and Cade Haskins. Credit: FOS

Unionization would allow athletes the opportunity to not just earn salaries but also have access to labor benefits like workers’ compensation, health care, and other legal protections.

For Haskins, who has dealt with multiple injuries during his college career, health-care benefits are a top priority. Other players cited pay: The Ivy League is the only conference in D-I that doesn’t allow athletic scholarships. Players receive need-based financial aid, but many still work extra jobs on the side to make ends meet. (The issue is the subject of a separate lawsuit against the conference.) “We want to be paid,” sophomore Jackson Munro told reporters after the game. But he doesn’t just want a scholarship like other athletes currently receive. “We want wages.”

Something the players will not be asking for: less practice time. They’re not complaining about their workload; they just want to be compensated for it. “If anybody believes that there is a single D-I athlete in the world that wants to go to his school and practice less, I don’t mean to be disrespectful to anybody, but they’re a fool,” senior Robert McRae III told reporters.

When the players decided to unionize this fall, they had a brief conversation with head coach David McLaughlin. They assured him that the effort would be an off-court venture and wouldn’t affect practice or games. Myrthil described McLaughlin’s reaction as “respectful.” He hasn’t come out in support of the effort but hasn’t criticized it either. The university probably wouldn’t allow him to admit he’s pro-union, anyway.

Unlike coaches, Dartmouth’s administration has attacked the players’ effort at every turn. SEIU Local 560 president Chris Peck, who has led multiple unionization efforts on campus, says he has never seen Dartmouth fight a unionization as hard as it’s fought against a men’s basketball union.

“Classifying these students as employees simply because they play basketball is as unprecedented as it is inaccurate,” Dartmouth said in a statement after the vote Tuesday.

Their arguments during an October virtual hearing and in court documents echo the NCAA’s pro-amateurism propaganda: Since players are students first, they can’t possibly also be workers. They’re not compensated, and therefore they’re not employees. Athletes play for a money-losing team, the school has claimed in court documents (though U.S. Department of Education data [[link removed]] suggests the team earns $1.3 million annually). And the NLRB shouldn’t exercise jurisdiction because it doesn’t have power over public schools, which make up much of D-I.

In her February ruling, NLRB regional director Laura Sacks disagreed on every point, saying students can be employees and students at the same time—that the shoes and free tickets they receive count as compensation, and that revenue generation isn’t a prerequisite for employment. The main issue is control exerted over players, which the regional director ascertained from grueling schedules and myriad rules. The Ivy League’s all-private-school makeup allowed her to exercise jurisdiction as well.

The school’s anti-union push didn’t stop in the courtroom, however. A document was distributed to all athletic department officials discouraging them from supporting unionization, Peck said.

The week before the vote, an athletic department official sent another letter to players warning that if they voted to unionize, they could get kicked out of the NCAA, an issue even McLaughlin appeared unconcerned about. The document, reviewed by FOS, also said unionization could jeopardize international athletes, who are not authorized to work while on F-class student visas. (Students with F-class visas are allowed to perform on-campus jobs but have limits on their hours.) Myrthil, from Sweden, and senior Dusan Neskovic, from Bosnia and Herzegovina, both said they believed in the union effort. “It’s something that we should support, as international students, in order to have a better experience as a Dartmouth student-athlete,” Neskovic told reporters.

Dartmouth’s last-ditch effort: It filed an unsuccessful motion asking to cancel the vote, or at least keep the results secret. The minute the vote ended, the school’s lawyer filed a prewritten appeal of the entire case to the NLRB’s national board. The school has hired the prestigious and (markedly pro-corporate) law firm Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, which is also representing USC in a separate NLRB athlete employment case.

Dartmouth did not threaten to cut the program altogether, as others have suggested, because that could be considered union-busting.

Members of the Dartmouth men’s basketball team arrive at the union election. Credit: FOS

News of the vote took over the sports news cycle. But on campus, the historic moment was met with minimal fanfare. No more than a dozen reporters and photographers camped out to meet the players (and three seniors arrived before the big group, since they wanted to drive and avoid the rain). A few union representatives applauded them as they approached and, like excited parents, made them pose for photos before going into the election.

“The walk down from the Hanover Inn to the place we voted was really cool, just because it was symbolic of something that our whole team—well, almost our whole team wanted,” Munro told reporters. “It was just really special to make some history.”

After voting, Myrthil and Haskins, who was wearing a heather-gray SEIU 560 sweatshirt, met informally with reporters on the lower level of the Hanover Inn. Upstairs, Dartmouth College management was holding a lunch meeting in a banquet hall, complete with a catered buffet. SEIU union members accompanying players jokingly held up their union signs outside the windows.

None of the players went back to watch the tally, instead returning to their normal activities. After all, they could barely fit voting into their schedules. (The Ivy Leaguers were not just in the middle of basketball season and a historic organizing effort but also finals week.) “I ran right from the vote to my [senior thesis] presentation,” senior Jaren Johnson said. “I was like five minutes late, but I still took care of business.” His senior thesis was on the impact of charter schools on student achievement in California.

Several players told reporters they didn’t even find out the results until hours later, right before tip-off.

The matchup against Harvard was the players’ last game of what was a memorable season off the court but a forgettable one on it. The Big Green were 5–21 going into Tuesday night’s game, ranking last in the Ivy League. Only about 800 people came to Leede Arena—but the presence of the union vote was in the building. SEIU members distributed pro-union bandanas and signs to fans, many of whom were current or former union members who came just to support their newest colleagues.

Susan Russell, the former secretary-treasurer of SEIU Local 560, arrived at the game wearing an SEIU 560 sweatshirt and grabbed a “unions for all” sign. “This is the beginning of players in all sports receiving some respect and dignity, which they don’t always get,” she says. “And maybe a little bit of side money, too, which is well deserved.”

Players celebrate after upsetting Harvard. Credit: FOS

The question over whether athletes should unionize has been hotly debated. But one thing the armchair experts can’t argue: that the union vote detracted from the Big Green’s on-court performance. The team battled back from a double-digit deficit to upset the Crimson, 76–69. A major contributor to that effort: Myrthil, who drilled a three-pointer with 1:13 to go to seal the win. The small but mighty crowd went wild as Myrthil raised his hands in celebration.

McLaughlin told reporters he was happy players got to voice their opinions on their organization effort but that “unionization is theirs, and theirs alone. My focus is on this great win tonight.”

By the time the players sat down for postgame interviews at 9 p.m., they were visibly exhausted. They’d taken finals, gone to class, attended office hours, played their last game of the season, and made history.

And the fight is far from over, as Dartmouth’s appeal could take years. Haskins and Myrthil assured reporters, however, that the underclassmen are prepared to see the union push through, even if the core junior class graduates before a final decision is handed down.

The team got its first real chance to celebrate Wednesday night during a group dinner at Han Fusion—a Chinese restaurant next door to the building where the election took place. They received black SEIU 560 hoodies and reflected over plates of fried rice and kung pao chicken.

“What we did [Tuesday] was historic,” Munro said, “and something I’ll remember for the rest of my life.” No appeals process or future court ruling can take that away.

SPONSORED BY WENDY’S

$1 Dave’s Single in the Wendy’s App

This March, you can get incredible deals on Wendy’s [[link removed]] Hamburgers made with fresh, never frozen, beef.

With Wendy’s in-app offers [[link removed]], you can get a Dave’s Single for one dollar and a two-dollar Dave’s Double. So keep your fandom going and bet on the only sure thing this month—Wendy’s fresh, never frozen, beef.

Enjoy the madness like never before. Download [[link removed]] the Wendy’s app and get going.

Editors’ Picks History in Hanover: Dartmouth Men’s Basketball Players Vote to Unionize [[link removed]]by Amanda Christovich [[link removed]]The team became the first in D-I to officially vote to unionize. Tommy Tuberville: Dartmouth Basketball Union ‘Will Absolutely Kill College Sports’ [[link removed]]by Margaret Fleming [[link removed]]The U.S. senator and former college football coach let it rip on Fox News. Dartmouth Men’s Basketball Employment Ruling: Everything You Need to Know [[link removed]]by Amanda Christovich [[link removed]]The impact, the appeals process, and where NCAA sports go from here. Advertise [[link removed]] Awards [[link removed]] Learning [[link removed]] Video [[link removed]] Podcast [[link removed]] Sports Careers [[link removed]] Written by Amanda Christovich [[link removed]] Edited by Peter Richman [[link removed]], Catherine Chen [[link removed]]

If this email was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here [[link removed]].

Update your preferences [link removed] / Unsubscribe [link removed]

Copyright © 2024 Front Office Sports. All rights reserved.

460 Park Avenue South, 7th Floor, New York NY, 10016

Read in Browser [[link removed]]

POWERED BY

Earlier this week, I took a five-hour bus ride from New York City up to Hanover, N.H., to cover the Dartmouth men’s basketball team’s union vote. The remote Ivy League campus with a six-win basketball team wasn’t the place anyone expected to be at the forefront of athletes’ rights advocacy—but its players produced a monumental day in college sports.

— Amanda Christovich [[link removed]]

‘We Want to Be Paid’: Inside Dartmouth Men’s Basketball’s Historic Union Effort

FOS

At around 12:15 p.m. on a cold and rainy Tuesday, 11 Dartmouth men’s basketball players took a short walk together from a campus hotel to the school’s human resources office. They looked like any normal, if tall, group of college students on the way to study, grab lunch, or hang out between classes. But they were actually headed to do something quite abnormal: deal a potential death blow to NCAA amateurism.

The Big Green became the first NCAA team in history to officially join a union, voting 13–2 to become members of the Service Employees International Union’s Local 560 chapter. The Dartmouth unionization effort, which began with a petition filed in September, is one of several cases challenging the NCAA’s model that bars players from being considered employees. In February, the NLRB regional director struck down that model, ruling players are employees and have the right to hold the election.

Within minutes of the vote tally, Dartmouth’s administration filed an appeal—a process that could continue all the way up to the Supreme Court. Nothing will change for players immediately until that process concludes. But if they win the lengthy appeals process, they’ll not only get to bargain for those benefits but also set a precedent that NCAA athletes nationwide could be legally entitled to do the same. The team has already potentially opened the floodgates, however: They hope to launch an Ivy League Players Union, and they have begun fielding questions from athletes at other Division I schools and conferences who could unionize themselves.

“It’s time for the age of amateurism to end,” player representatives Cade Haskins and Romeo Myrthil, both juniors, said in a statement after the vote. They’re one step closer to making that dream a reality.

When Haskins isn’t practicing or studying, he works at the snack bar of the Dartmouth dining hall. A member of the dining hall workers union, Haskins was inspired by the collective bargaining effort that won his coworkers double the salary, extra paid time off, and other perks. He wondered whether the SEIU’s union effort might help ameliorate circumstances for his teammates.

Haskins and Myrthil, as well as the rest of the junior class, started discussing unionizing during team meals in the summer, Haskins told Front Office Sports before the vote. The group began setting up Zoom calls with the rest of the players. Ultimately, the team agreed to approach the SEIU and file a union petition with the NLRB in September.

Romeo Myrthil (left) and Cade Haskins. Credit: FOS

Unionization would allow athletes the opportunity to not just earn salaries but also have access to labor benefits like workers’ compensation, health care, and other legal protections.

For Haskins, who has dealt with multiple injuries during his college career, health-care benefits are a top priority. Other players cited pay: The Ivy League is the only conference in D-I that doesn’t allow athletic scholarships. Players receive need-based financial aid, but many still work extra jobs on the side to make ends meet. (The issue is the subject of a separate lawsuit against the conference.) “We want to be paid,” sophomore Jackson Munro told reporters after the game. But he doesn’t just want a scholarship like other athletes currently receive. “We want wages.”

Something the players will not be asking for: less practice time. They’re not complaining about their workload; they just want to be compensated for it. “If anybody believes that there is a single D-I athlete in the world that wants to go to his school and practice less, I don’t mean to be disrespectful to anybody, but they’re a fool,” senior Robert McRae III told reporters.

When the players decided to unionize this fall, they had a brief conversation with head coach David McLaughlin. They assured him that the effort would be an off-court venture and wouldn’t affect practice or games. Myrthil described McLaughlin’s reaction as “respectful.” He hasn’t come out in support of the effort but hasn’t criticized it either. The university probably wouldn’t allow him to admit he’s pro-union, anyway.

Unlike coaches, Dartmouth’s administration has attacked the players’ effort at every turn. SEIU Local 560 president Chris Peck, who has led multiple unionization efforts on campus, says he has never seen Dartmouth fight a unionization as hard as it’s fought against a men’s basketball union.

“Classifying these students as employees simply because they play basketball is as unprecedented as it is inaccurate,” Dartmouth said in a statement after the vote Tuesday.

Their arguments during an October virtual hearing and in court documents echo the NCAA’s pro-amateurism propaganda: Since players are students first, they can’t possibly also be workers. They’re not compensated, and therefore they’re not employees. Athletes play for a money-losing team, the school has claimed in court documents (though U.S. Department of Education data [[link removed]] suggests the team earns $1.3 million annually). And the NLRB shouldn’t exercise jurisdiction because it doesn’t have power over public schools, which make up much of D-I.

In her February ruling, NLRB regional director Laura Sacks disagreed on every point, saying students can be employees and students at the same time—that the shoes and free tickets they receive count as compensation, and that revenue generation isn’t a prerequisite for employment. The main issue is control exerted over players, which the regional director ascertained from grueling schedules and myriad rules. The Ivy League’s all-private-school makeup allowed her to exercise jurisdiction as well.

The school’s anti-union push didn’t stop in the courtroom, however. A document was distributed to all athletic department officials discouraging them from supporting unionization, Peck said.

The week before the vote, an athletic department official sent another letter to players warning that if they voted to unionize, they could get kicked out of the NCAA, an issue even McLaughlin appeared unconcerned about. The document, reviewed by FOS, also said unionization could jeopardize international athletes, who are not authorized to work while on F-class student visas. (Students with F-class visas are allowed to perform on-campus jobs but have limits on their hours.) Myrthil, from Sweden, and senior Dusan Neskovic, from Bosnia and Herzegovina, both said they believed in the union effort. “It’s something that we should support, as international students, in order to have a better experience as a Dartmouth student-athlete,” Neskovic told reporters.

Dartmouth’s last-ditch effort: It filed an unsuccessful motion asking to cancel the vote, or at least keep the results secret. The minute the vote ended, the school’s lawyer filed a prewritten appeal of the entire case to the NLRB’s national board. The school has hired the prestigious and (markedly pro-corporate) law firm Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, which is also representing USC in a separate NLRB athlete employment case.

Dartmouth did not threaten to cut the program altogether, as others have suggested, because that could be considered union-busting.

Members of the Dartmouth men’s basketball team arrive at the union election. Credit: FOS

News of the vote took over the sports news cycle. But on campus, the historic moment was met with minimal fanfare. No more than a dozen reporters and photographers camped out to meet the players (and three seniors arrived before the big group, since they wanted to drive and avoid the rain). A few union representatives applauded them as they approached and, like excited parents, made them pose for photos before going into the election.

“The walk down from the Hanover Inn to the place we voted was really cool, just because it was symbolic of something that our whole team—well, almost our whole team wanted,” Munro told reporters. “It was just really special to make some history.”

After voting, Myrthil and Haskins, who was wearing a heather-gray SEIU 560 sweatshirt, met informally with reporters on the lower level of the Hanover Inn. Upstairs, Dartmouth College management was holding a lunch meeting in a banquet hall, complete with a catered buffet. SEIU union members accompanying players jokingly held up their union signs outside the windows.

None of the players went back to watch the tally, instead returning to their normal activities. After all, they could barely fit voting into their schedules. (The Ivy Leaguers were not just in the middle of basketball season and a historic organizing effort but also finals week.) “I ran right from the vote to my [senior thesis] presentation,” senior Jaren Johnson said. “I was like five minutes late, but I still took care of business.” His senior thesis was on the impact of charter schools on student achievement in California.

Several players told reporters they didn’t even find out the results until hours later, right before tip-off.

The matchup against Harvard was the players’ last game of what was a memorable season off the court but a forgettable one on it. The Big Green were 5–21 going into Tuesday night’s game, ranking last in the Ivy League. Only about 800 people came to Leede Arena—but the presence of the union vote was in the building. SEIU members distributed pro-union bandanas and signs to fans, many of whom were current or former union members who came just to support their newest colleagues.

Susan Russell, the former secretary-treasurer of SEIU Local 560, arrived at the game wearing an SEIU 560 sweatshirt and grabbed a “unions for all” sign. “This is the beginning of players in all sports receiving some respect and dignity, which they don’t always get,” she says. “And maybe a little bit of side money, too, which is well deserved.”

Players celebrate after upsetting Harvard. Credit: FOS

The question over whether athletes should unionize has been hotly debated. But one thing the armchair experts can’t argue: that the union vote detracted from the Big Green’s on-court performance. The team battled back from a double-digit deficit to upset the Crimson, 76–69. A major contributor to that effort: Myrthil, who drilled a three-pointer with 1:13 to go to seal the win. The small but mighty crowd went wild as Myrthil raised his hands in celebration.

McLaughlin told reporters he was happy players got to voice their opinions on their organization effort but that “unionization is theirs, and theirs alone. My focus is on this great win tonight.”

By the time the players sat down for postgame interviews at 9 p.m., they were visibly exhausted. They’d taken finals, gone to class, attended office hours, played their last game of the season, and made history.

And the fight is far from over, as Dartmouth’s appeal could take years. Haskins and Myrthil assured reporters, however, that the underclassmen are prepared to see the union push through, even if the core junior class graduates before a final decision is handed down.

The team got its first real chance to celebrate Wednesday night during a group dinner at Han Fusion—a Chinese restaurant next door to the building where the election took place. They received black SEIU 560 hoodies and reflected over plates of fried rice and kung pao chicken.

“What we did [Tuesday] was historic,” Munro said, “and something I’ll remember for the rest of my life.” No appeals process or future court ruling can take that away.

SPONSORED BY WENDY’S

$1 Dave’s Single in the Wendy’s App

This March, you can get incredible deals on Wendy’s [[link removed]] Hamburgers made with fresh, never frozen, beef.

With Wendy’s in-app offers [[link removed]], you can get a Dave’s Single for one dollar and a two-dollar Dave’s Double. So keep your fandom going and bet on the only sure thing this month—Wendy’s fresh, never frozen, beef.

Enjoy the madness like never before. Download [[link removed]] the Wendy’s app and get going.

Editors’ Picks History in Hanover: Dartmouth Men’s Basketball Players Vote to Unionize [[link removed]]by Amanda Christovich [[link removed]]The team became the first in D-I to officially vote to unionize. Tommy Tuberville: Dartmouth Basketball Union ‘Will Absolutely Kill College Sports’ [[link removed]]by Margaret Fleming [[link removed]]The U.S. senator and former college football coach let it rip on Fox News. Dartmouth Men’s Basketball Employment Ruling: Everything You Need to Know [[link removed]]by Amanda Christovich [[link removed]]The impact, the appeals process, and where NCAA sports go from here. Advertise [[link removed]] Awards [[link removed]] Learning [[link removed]] Video [[link removed]] Podcast [[link removed]] Sports Careers [[link removed]] Written by Amanda Christovich [[link removed]] Edited by Peter Richman [[link removed]], Catherine Chen [[link removed]]

If this email was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here [[link removed]].

Update your preferences [link removed] / Unsubscribe [link removed]

Copyright © 2024 Front Office Sports. All rights reserved.

460 Park Avenue South, 7th Floor, New York NY, 10016

Message Analysis

- Sender: Front Office Sports

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor