|  | Know better. Do better. |  | Climate. Change.News from the ground, in a warming world |

|

| | | By Jack Graham | Climate change and nature correspondent, UK | | |

|  |

| Britain’s oil declineI thought I knew what a strong wind felt like, and then I went to Shetland. The islands, 100 miles north of Scotland's mainland, are the windiest part of Britain.

As I walked through the main town of Lerwick, I had to lean my body far forward to avoid being swept off my feet. I eventually reached my destination: a bar where young musicians play traditional music each week. They only start worrying when the wind gets above 50 miles per hour, a local told me over a beer.

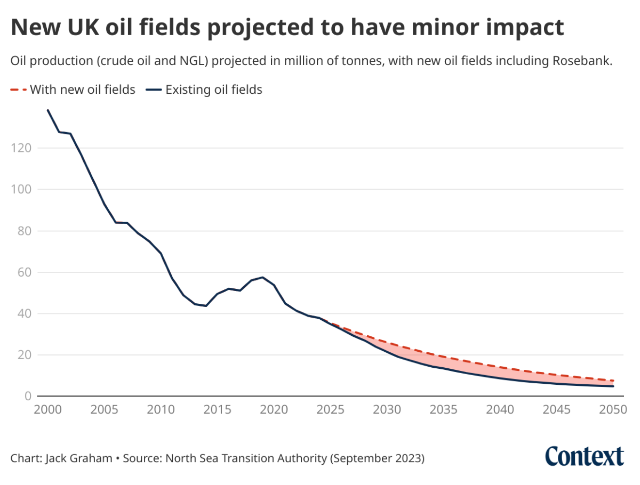

The islands – home to 21,000 people – grew wealthy after the discovery of offshore oil and gas fields 50 years ago, and the resulting construction of Sullom Voe, one of the biggest oil terminals in Europe. But that business is in sharp decline now, and this despite the British government’s plan to grant hundreds of new licences and give the green light to the development of Rosebank - the country's largest untapped oil and gas field.

For my story this week, I looked into how Shetland is looking to harness the wind to fill the gap. The islands hope that developing new energy forms, like wind power and green hydrogen, can replace the hundreds of millions of pounds earned from Shetland’s position as a hub for the oil and gas industry over the years.

This is a question facing many regions around the world. Our energy is often powered by major infrastructure in remote places. Many of these regions are financially reliant on industries based on fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas. So can clean energy replace them, and what will it mean for those communities?  Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham |

Viking returnsShetland is eyeing the potential of wind power and eventually green hydrogen, which could power industries and vehicles. Green hydrogen tech is in its early stages, but it

involves extracting hydrogen from water using electrolysis in a process powered by renewables.

On my trip, I visited Viking Energy, which is set to become Shetland’s largest wind farm when it comes online this year, with 103 turbines reaching 155 metres tall. It's expected to power almost half a million homes via a new cable to Britain's mainland.

With these huge turbines lining the hills along the centre of Shetland's biggest island, it's no wonder the development has been the subject of huge debate, with court cases and delays spanning several years. Viking is paying a community benefit of 2.2 million pounds ($2.79 million) every year, but this pales in comparison to Shetland's oil and gas income.  Viking Energy says it is restoring nearly three times the areas of peatland impacted by its 103 turbines, on Mainland, Shetland, Scotland, November 1, 2023. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Jack Graham |

For those opposed to the project, an added frustration is that energy costs in Shetland - colder and darker than the rest of Britain - are far higher, so they're not seeing the benefit in their energy bills. When you include food and travel, the cost of living is between 20% and 65% higher in Shetland, according to the council.

Daniel Gear, who directs a consultancy called Voar Energy in Shetland, summarised this issue rather neatly: "The interests of the host community can be diluted against the interests of a nation."

What's the answer to this problem? Blowin' in the wind, perhaps.

See you next week,

Jack |

|

|

| | Companies that clear forest may end up profiting from the Green Credit Programme, which aims to protect the environment | Tuvalu is among nations digitising heritage in the face of climate impacts, but there are concerns around cost, access and control | With protests by farmers raging from Germany to Greece, EU policymakers have agreed concessions on long-standing environmental goals | |

| |

| | | |

|