February 15, 2024

Permission to republish original opeds and cartoons granted.

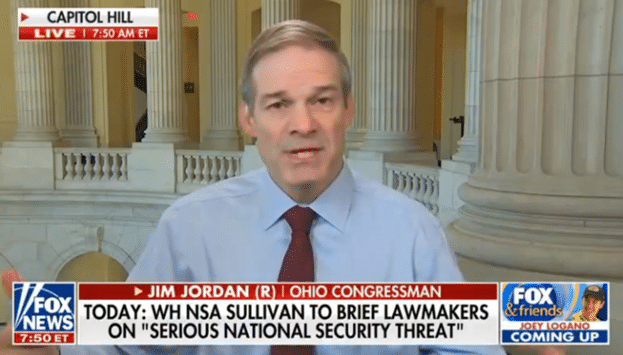

House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan: Probable cause warrants ‘ha[ve] to be in the bill, or we shouldn’t reauthorize FISA. It has to be in there.’

By Robert Romano

House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan (R-Ohio) is a no vote on the latest bid by the House of Representatives to renew authorization of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) after his own committee’s bipartisan proposal, “The Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act,” to rein in the nation’s intelligence agencies, the Justice Department and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was gutted by the House Intelligence Committee and reintroduced as H.R. 7320.

In an interview with Fox News’ Brian Kilmeade, Jordan declared, “the way our system works is there are separate and equal branches of government, you can't just have the executive branch police themselves, you have to go to another branch of government, the judicial branch, to get a probable cause warrant.”

But it’s not in the new bill, Jordan warned, saying that in every other judicial process there’s a warrant, but not in FISA: “That happens all the time, every single day in this country, that is a standard we've had around since the place started. So let's make sure that same standard exists particularly when we know that the FBI abused this process 278,000 times they didn't follow their rules, improperly quer[ying] this database.”

And if it wasn’t in the final bill, then Jordan said he opposed FISA reauthorization: “So that is a huge issue that has to be in the bill or we should not reauthorize FISA. It has to be in there.”

The House Judiciary Committee version of the bill would have prohibited accessing surveillance of American citizens located in the United States for non-intelligence purposes without a search warrant for “law enforcement purposes,” stating, “no officer or employee of the United States may conduct a query of information acquired under this section in an effort to find communications or information the compelled production of which would require a probable cause warrant if sought for law enforcement purposes in the United States, of or about 1 or more United States persons or persons reasonably believed to be located in the United States at the time of the query or the time of the communication or creation of the information.”

That is, unless one of four exceptions apply: 1) the person is believed to be an agent of a foreign power or the Attorney General is telling the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court that there is an emergency that requires an emergency physical search: “such person is the subject of an order or emergency authorization authorizing electronic surveillance or physical search under section 105 or 304 of this Act, or a warrant issued pursuant to the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure by a court of competent jurisdiction covering the period of the query…”; 2) there must be an imminent danger to life and limb and there’s simply no time to get to the proper court of jurisdiction: “an emergency exists involving an imminent threat of death or serious bodily harm; and… in order to prevent or mitigate this threat, the query must be conducted before authorization [under the law] can, with due diligence, be obtained; and… a description of the query is provided to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court and the congressional intelligence committees and the Committees on the Judiciary of the House of Representatives and of the Senate in a timely manner.”; 3) there must be an attempt to find malicious software being deployed to see who is being targeted by the malware: “the query uses a known cybersecurity threat signature as a query term; … the query is conducted, and the results of the query are used, for the sole purpose of identifying targeted recipients of malicious software and preventing or mitigating harm from such malicious software; … no additional contents of communications retrieved as a result of the query are accessed or reviewed; … all such queries are reported to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.”; or 4) if the U.S. person consented to be surveilled for whatever reason: “such person or, if such person is incapable of providing consent, a third party legally authorized to consent on behalf of such person, has provided consent to the query on a case-by-case basis…”

Section 105 refers to 50 U.S. Code § 1805(a)(2)(A), which allows surveillance of U.S. persons believed to be agents of a foreign power: “the target of the electronic surveillance is a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power: Provided, That no United States person may be considered a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power solely upon the basis of activities protected by the first amendment to the Constitution of the United States.”

Section 304 refers to emergency orders under 50 U.S. Code § 1824(e)(1), which allows for surveillance when the Attorney General “reasonably determines that an emergency situation exists with respect to the employment of a physical search to obtain foreign intelligence information before an order authorizing such physical search can with due diligence be obtained; … reasonably determines that the factual basis for issuance of an order under this subchapter to approve such physical search exists; …. informs, either personally or through a designee, a judge of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court at the time of such authorization that the decision has been made to employ an emergency physical search; and … makes an application in accordance with this subchapter to a judge of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court as soon as practicable, but not more than 7 days after the Attorney General authorizes such physical search.”

This second exception appears similar to the emergency orders under Section 304, however, 304 still applies to surveillance based on whether the person is supposed to be a foreign agent and is supposed to be about gathering foreign intelligence. Whereas the new exception has to do with a danger of an imminent attack of some sort and if the section is invoked then it still goes to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, but it also goes to the House and Senate Intelligence and Judiciary Committees.

The Judiciary Committee proposal also would have created additional restrictions and limits on how information gathered for foreign intelligence or emergency purposes can be used in a criminal context, requiring the Attorney General to authorize it and when it is related to some sort of attack on the U.S., counterintelligence or drug cartels: “the commission of a Federal crime of terrorism …. [or] actions necessitating counterintelligence (as defined in section 3 of the National Security Act of 1947 (50 U.S.C. 3003)) … [or] the proliferation or the use of a weapon of mass destruction … [or] a cybersecurity breach or attack from a foreign country …. [or] incapacitation or destruction of critical infrastructure … [or] an attack against the armed forces of the United States or an ally of the United States or to other personnel of the United States Government or a government of an ally of the United States; or … international narcotics trafficking.”

On the “actions necessitating counterintelligence” provision, counterintelligence is defined under 50 U.S.C. § 3003 as “information gathered, and activities conducted, to protect against espionage, other intelligence activities, sabotage, or assassinations conducted by or on behalf of foreign governments or elements thereof, foreign organizations, or foreign persons, or international terrorist activities.”

And then if the target of an investigation happens to be a member of a U.S. political organization, including a presidential or Congressional campaign or any other campaign for public office, then the matter gains heightened scrutiny at the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court and would invoke new adversarial proceedings, in which case the court “shall… appoint 1 or more individuals who have been designated… not fewer than 1 of whom possesses privacy and civil liberties expertise, unless the court finds that such a qualification is inappropriate, to serve as amicus curiae to assist the court in the consideration of any application or motion for an order or review that, in the opinion of the court… presents a novel or significant interpretation of the law; … presents significant concerns with respect to the activities of a United States person that are protected by the first amendment to the Constitution of the United States; …. presents or involves a sensitive investigative matter; … presents a request for approval of a new program, a new technology, or a new use of existing technology; … presents a request for reauthorization of programmatic surveillance; … otherwise presents novel or significant civil liberties issues; or … otherwise involves the activities of a United States person…” in which a “sensitive investigative matter” would be defined as “a domestic public official or political candidate, or an individual serving on the staff of such an official or candidate; … a domestic religious or political organization, or a known or suspected United States person prominent in such an organization; … the domestic news media; or… any other investigative matter involving a domestic entity or a known or suspected United States person that, in the judgment of the applicable court … is as sensitive as an investigative matter.”

This all would have created an adversarial proceeding at the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. That is, “unless the court issues a finding that appointment is not appropriate.”

It’s worth noting that even with these protections proposed by the House Judiciary Committee, these reforms would not have prohibited the Carter Page FISA warrant issued in 2016 against the Trump campaign per se, which was issued because Page was suspected of being a foreign agent. The Oct. 2016 application to the FISA Court stated, “The target of this application is Carter W. Page, a U.S. person, and an agent of a foreign power… The status of the target was determined in or about October 2016 from information provided by the U.S. State Department…”

As noted earlier, to make the accusation, as the FBI and the Justice Department had to give the FISA Court a “statement of the facts and circumstances relied upon by the applicant to justify his belief that… the target of the electronic surveillance is a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power…” under 50 U.S. Code § 1805(a)(2)(A).

And yet, these minimal protections, provided for in the House Judiciary Committee legislation, which was referred Dec. 6, 2023 on an overwhelming bipartisan vote of 35-2, are no where to be found in the new legislation now before the House Rules Committee.

Jordan told Fox News that he was still working to ensure that these protections can get back into the final bill: “I spent most of the day yesterday trying to figure out this FISA law, which is up for reauthorization, and particularly the protections the American people need when the government, the United States government, the federal government's going to be looking at their data. We think you have to have a warrant before you do that, and so we're fighting to make sure that gets done over the next several weeks as part of this FISA reauthorization.”

But it’s not going to be easy, if it is even possible. Despite overwhelming bipartisan support for FISA reforms, it is unclear what would happen if the Judiciary Committee bill were offered as a substitute on the floor — or if it will even be allowed on the floor. As usual, stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.

Cartoon: The Three Amigos

By A.F. Branco