Email

The return of failed criminal legal system policies – and how to fight back

| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | The return of failed criminal legal system policies – and how to fight back |

| Date | January 24, 2024 5:54 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

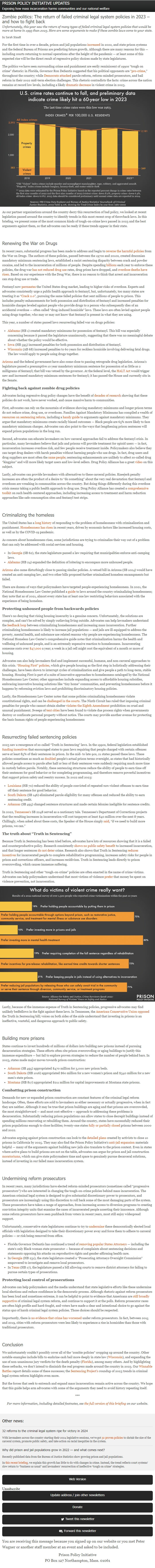

Crime is approaching 60-year lows, so why are lawmakers pushing these failed policies?

Prison Policy Initiative updates for January 24, 2024 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Zombie politics: The return of failed criminal legal system policies in 2023 – and how to fight back [[link removed]] Unfortunately, this year saw the return of many types of failed criminal legal system policies that would be more at home in 1993 than 2023. Here are some arguments to make if these zombie laws come to your state. [[link removed]]

by Sarah Staudt

For the first time in over a decade, prison and jail populations increased [[link removed]] in 2022, and state prison systems and the federal Bureau of Prisons are predicting future growth. Although there are many reasons for this — including courts returning to normal operations after the height of the pandemic — at least some of this expected rise will be the direct result of regressive policy choices made by state legislatures.

The politics we have seen surrounding crime and punishment are eerily reminiscent of 1990s “tough on crime” rhetoric: in Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis suggested that his political opponents are “ pro-crime [[link removed]],” throughout the country; while Democrats [[link removed]] attacked [[link removed]] parole reform, reform-minded prosecutors, and bail reform in their 2022 mid-term election challenges. This rhetoric contradicts the facts: crime across the nation remains at record low levels, including a likely dramatic decrease [[link removed]] in violent crime in 2023.

As our partner organizations around the country decry this resurrection of bad policy, we looked at recent legislation passed around the country to identify trends in this most recent crop of throwback laws. In this briefing, we present some of the most common kinds of tough-on-crime laws passed in 2023 and the best arguments against them, so that advocates can be ready if these trends appear in their state.

Renewing the War on Drugs

In recent years, substantial progress has been made to address and begin to reverse the harmful policies [[link removed]] from the War on Drugs. The authors of these policies, passed between the 1970s and 2010s, created draconian mandatory minimum sentencing laws, established a racist sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine, and led to the incarceration of millions of people. Despite spending billions [[link removed]] each year to enforce these policies, the drug war has not reduced drug use [[link removed]] rates, drug prices have dropped, and overdose deaths have [[link removed]] risen [[link removed]]. Based on our experience with the Drug War, there is no reason to think that arrest and incarceration can stop drug use or trade.

Fentanyl now permeates [[link removed]] the United States drug market, leading to higher risks of overdose. Experts and advocates consistently urge a public health approach to fentanyl, but, unfortunately, too many states are treating it as “ Crack 2.0 [[link removed]]”, pursuing the same failed policies that sent millions of people to prison. This includes penalty enhancements for both possession and distribution of fentanyl and increased penalties for homicide charges leveled against people who provide drugs to a person who subsequently dies of an accidental overdose — often called “drug-induced homicide” laws. These laws are often levied against people using drugs together, who may or may not know that fentanyl is present in what they are using.

This year, a number of states passed laws resurrecting failed war on drugs policies:

Alabama [[link removed]] (HB 1) created mandatory minimums for possession of fentanyl. This bill was especially concerning because it passed the legislature unanimously, suggesting that there was no meaningful debate about whether the policy would be effective. Iowa [[link removed]] (HB 595) increased penalties for both possession and distribution of fentanyl. Wisconsin [[link removed]] (AB 68) increased penalties to 60 years for reckless homicide involving delivering fatal drugs. The law would apply to people using drugs together.

Arizona [[link removed]] and the federal government have also come close to passing retrograde drug legislation. Arizona’s legislature passed a presumptive 10 year mandatory minimum sentence for possession of as little as 2 milligrams of fentanyl; that bill was vetoed by the governor. At the federal level, the HALT Act [[link removed]]would trigger new and increased mandatory minimum sentences for fentanyl; it has passed the House and currently sits in the Senate.

Fighting back against zombie drug policies

Advocates facing regressive drug policy changes have the benefit of decades of research [[link removed]] showing that these policies do not work, have never worked, and cause massive harm to communities.

First, advocates can rely on the mountain of evidence showing mandatory minimums and longer prison terms do not reduce crime, drug use, or overdoses. Families Against Mandatory Minimums has compiled a wealth of resources on sentencing reform [[link removed]], including a handy guide [[link removed]] to arguments against mandatory minimums. They argue that mandatory minimums create racially biased outcomes — Black people are 65% more likely to face mandatory minimum charges. Advocates can also point to the ways that lengthening prison sentences will expand prison populations in the long run.

Second, advocates can educate lawmakers on how carceral approaches fail to address the fentanyl crisis. In particular, many lawmakers believe that jails and prisons will provide treatment for opioid users — in fact, incarceration increases overdose risk, and few people receive treatment inside. Policymakers also believe they can target drug dealers with harsh penalties without harming people who use drugs. In fact, drug users and drug suppliers are most often the same people [[link removed]]; sentencing enhancements are unlikely to affect so-called drug “kingpins” and will more likely target users and low-level sellers. Drug Policy Alliance has a great video [[link removed]] on this subject.

Lastly, advocates can provide lawmakers with alternatives to these carceral policies. Kneejerk penalty increases are often the product of a desire to “do something” about the very real devastation that fentanyl and overdoses are wreaking in communities across the country. But doing things differently during this overdose crisis means taking a public health approach to drug use. Drug Policy Alliance has created a comprehensive toolkit [[link removed]] on such health-centered approaches, including increasing access to treatment and harm reduction approaches like safe consumption sites and fentanyl test strips.

Criminalizing the homeless

The United States has a long history [[link removed]] of responding to the problem of homelessness with criminalization and punishment. Homelessness has risen [[link removed]] in recent years, driven by economic factors like increased housing costs, as well as by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As concern about homelessness rises, some jurisdictions are trying to criminalize their way out of a problem that can only be addressed with social services and housing.

In Georgia [[link removed]](SB 62), the state legislature passed a law requiring that municipalities enforce anti-camping laws. Alabama [[link removed]] (HB 24) expanded the definition of loitering to encompass more unhoused people.

Arizona [[link removed]] also came disturbingly close to passing similar policies. A vetoed bill in Arizona (SB 1024) would have created an anti-camping law, and two other bills proposed further criminalized homeless encampments but failed.

There are dozens of ways that policymakers have targeted people experiencing homelessness. In 2021, the National Homelessness Law Center published a guide [[link removed]] to laws around the country criminalizing homelessness; they note that as of 2021, almost every state has at least one law restricting behaviors associated with the experience of being homeless.

Protecting unhoused people from backwards policies

There’s no denying that rising housing insecurity is a genuine concern. Unfortunately, the solutions are complex, and can’t be solved by simply outlawing living outside. Advocates can help lawmakers understand the feedback loop [[link removed]] between criminalizing homelessness and increasing mass incarceration. Further criminalizing homelessness is likely to increase jail populations — and jails are ill-equipped to address the poverty, mental health, and substance use related reasons why people are experiencing homelessness. The National Homeless Law Center’s comprehensive guide notes that criminalization harms the health and wellbeing of unhoused people, and is an extremely expensive reaction to homelessness. Incarcerating someone costs over $47,000 [[link removed]] a year; a week in a jail cell might cost the equivalent of a month or more of housing.

Advocates can also help lawmakers find and implement successful, humane, and non-carceral approaches to this crisis. “Housing First” policies [[link removed]], which give people housing as the first step in holistically addressing their challenges, have been shown to interrupt cycles of criminalization and give people a path to long-term, stable housing. Housing First is part of a suite of innovative approaches to homelessness cataloged by the National Homelessness Law Center; other approaches include expanding access to affordable housing subsidies, embracing innovative housing solutions like “tiny home” communities, and preventing homelessness before it happens by reforming eviction laws and prohibiting discriminatory housing policies.

Lastly, the Homelessness Law Center notes that some policies criminalizing homelessness violate constitutional rights, and can be challenged in the courts [[link removed]]. The Ninth Circuit has ruled that imposing criminal penalties for people who cannot obtain shelter violates the Eighth Amendment [[link removed]] prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. Sweeps of tent cities [[link removed]] have been found to violate due process rights when governments destroy or confiscate personal property without notice. The courts may provide another avenue for protecting the basic human rights of people experiencing homelessness

Resurrecting failed sentencing policies

2023 saw a resurgence of so-called “Truth in Sentencing” laws. In the 1990s, federal legislation established funding incentives [[link removed].] that encouraged states to pass laws requiring that people charged with certain offenses serve at least 85% of their sentences in prison. In the mid- to late 90s, 21 states passed these laws. These policies sometimes as much as doubled [[link removed]] people’s actual prison terms overnight, as states that had historically allowed people access to parole after half or less of their sentences were suddenly requiring much more time in custody before parole. Notably, these sentencing structures reduce the ability of people to earn time off their sentences for good behavior or for completing programming, and therefore remove powerful incentives that support prison safety and reentry success. In 2022 and 2023:

Louisiana [[link removed]] (HB 70) reduced the ability of people convicted of repeated non-violent offenses to earn time off their sentence for good behavior. South Dakota [[link removed]] (SB 146) eliminated parole eligibility for many offenses and reduced the ability to earn sentencing credit. Arkansas [[link removed]] (SB 495) changed sentence structures and made certain felonies ineligible for sentence credits.

In 2022, Tennessee’s [[link removed]] SB 2248 served as a cautionary tale. Tennessee’s Department of Corrections projects that the resulting increases in incarceration will cost taxpayers at least $40 million over the next 8 years. Chillingly, when asked about these costs, the Speaker of the House simply said [[link removed]], “if we need to build more prisons, we can.”

The truth about “Truth in Sentencing”

Because Truth in Sentencing has been tried before, advocates have lots of resources showing that it is a failed and counterproductive policy. Research consistently shows no public safety benefit [[link removed]] to increased incarceration, and that longer sentences do not deter [[link removed]] crime. Research also shows that Truth in Sentencing reduces incentives [[link removed]] for incarcerated people to complete rehabilitative programming, increases safety risks for people in prison and corrections officers, and increases recidivism. Truth in Sentencing leads directly to prison overcrowding, which causes immense suffering.

Truth in Sentencing and other “tough-on-crime” policies are often enacted in the name of crime victims. Advocates can help policymakers understand that most victims of violence prefer [[link removed]] that money be spent on violence prevention, not incarceration.

Lastly, because of the immense expense of Truth in Sentencing policies, progressive advocates may find unlikely bedfellows in the fight against these laws. In Tennessee, the American Conservative Union opposed [[link removed]] the Truth in Sentencing bill; voices on both sides of the aisle understand that investing in prisons is an ineffective, wasteful, and dangerous approach to public safety.

Building more prisons

States continue to invest hundreds of millions of dollars into building new prisons instead of pursuing decarceration strategies. These efforts often cite prison overcrowding or aging buildings to justify this immense expenditure — but fail to explore proven strategies to reduce the number of people behind bars. In 2023, states made major moves towards prison construction:

Arkansas [[link removed]] (SB 495) appropriated $470 million for 3,000 new prison beds. South Dakota [[link removed]] (HB 1016) appropriated $60 million for a new women’s prison and $340 million for a new men’s state prison. Montana [[link removed]] (HB 817) appropriated $211 million for capital improvements at Montana state prisons. Combatting prison construction

Demands for new or expanded prison construction are constant features of the criminal legal reform landscape. Often, these efforts are sold to lawmakers as either necessary or actually progressive, when in fact they are neither. Although it may be true that prison buildings are aging and that prisons are overcrowded, the most straightforward — and most cost-effective — approach to addressing these problems is decarceration. Substantially reducing prison populations can allow states to close decrepit buildings instead of spending millions renovating or rebuilding them. Around the country, states have successfully reduced their prison populations enough to close facilities; twenty-one states fully or partially closed [[link removed]] prisons between 2000 and 2022.

Advocates arguing against prison construction can look to the detailed [[link removed]] plans [[link removed]] created by activists to close 10 prisons in California by 2025. They may also find the Prison Policy Initiative’s anti-jail expansion [[link removed]] materials helpful — many of the arguments against building new jails also translate to the prison context. Even in states where active plans to build prisons are not on the table, advocates can argue for prison and jail construction moratoriums [[link removed]], which can give state policymakers time and space to genuinely pursue decarceral solutions, instead of investing in our failed mass incarceration system.

Undermining reform prosecutors

In recent years, many jurisdictions have elected reform-minded prosecutors (sometimes called “progressive prosecutors”) who are interested in changing the tough-on-crime policies behind mass incarceration. The American criminal legal system is designed to give substantial discretionary power to prosecutors, and prosecutors are increasingly using this discretion to roll back some of the most damaging parts of the system. These prosecutors have taken a range of approaches, from increasing access to diversion programs to creating conviction integrity units that examine the cases of incarcerated people asserting their innocence. Although some reform prosecutors have seen pushback from voters in recent years, most still enjoy widespread support.

Unfortunately, conservative state legislatures continue to try to undermine [[link removed]] these democratically elected local officials with legislation designed to take their discretionary power away and force them to adhere to carceral policies — or risk being removed from office.

Florida Governor DeSantis has continued a trend of removing popular States Attorneys [[link removed]] — including the state’s only Black woman state prosecutor — because of complaints about sentencing decisions and statements opposing his attacks on reproductive rights and gender-affirming health care. In Georgia [[link removed]] (HB 231), the state legislature created a “Prosecuting Attorneys Oversight Commission” empowered to investigate and remove local prosecutors. In Texas [[link removed]] (HB 17), the legislature passed a bill allowing courts to remove district attorneys for failing to pursue certain types of prosecutions. Protecting local control of prosecutions

Advocates can help policymakers and the media understand that state legislative efforts like these undermine local elections and reduce confidence in the democratic process. Although rhetoric against reform prosecutors has been loud and sometimes extreme, it can be helpful to point to evidence that Americans are still broadly supportive [[link removed]] of criminal legal system reform, and continue to support it at the polls. Reform prosecutor races are often high profile and hard-fought, and voters have made a clear and intentional choice to go against the status quo of harsh criminal legal system policies. Those choices should be respected.

Importantly, there is no evidence that crime has worsened [[link removed]] under reform prosecutors. In fact, between 2015 and 2019, cities with reform prosecutors were less likely to experience a rise in homicides than those with traditional prosecutors.

Conclusion

We unfortunately couldn’t possibly cover all of the “zombie policies” cropping up around the country. Other notable examples include bills to enshrine cash bail more deeply in state law ( Wisconsin [[link removed]]), and expanding the use of non-unanimous jury verdicts for the death penalty ( Florida [[link removed]]), among many others. And by highlighting these setbacks, we don’t intend to diminish the real progress made around the country in 2023. Our Winnable Battles [[link removed]] report details some of these successes; the Sentencing Project’s [[link removed]] roundup of 2023 trends in criminal legal system reform highlights even more.

But the forces that seek to entrench and expand mass incarceration remain active across the country. We hope that this guide helps arm advocates with some of the arguments they need to avoid history repeating itself.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: 32 reforms to the criminal legal system ripe for victory in 2024 [[link removed]]

With lawmakers across the country starting their 2024 legislative sessions, we've got 32 proven policies [[link removed]] to shrink the size of the carceral system, promote public safety, and take action on racial inequities in the system.

Why did prison and jail populations grow in 2022 — and what comes next? [[link removed]]

Recently published data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics show growing prison and jail populations.

In this recent briefing [[link removed]], we explain this growth has little to do with changes in crime. Instead, the trend reflects court systems’ slow return to “business as usual” and lawmakers’ resurrection of ineffective “tough on crime” strategies.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for January 24, 2024 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Zombie politics: The return of failed criminal legal system policies in 2023 – and how to fight back [[link removed]] Unfortunately, this year saw the return of many types of failed criminal legal system policies that would be more at home in 1993 than 2023. Here are some arguments to make if these zombie laws come to your state. [[link removed]]

by Sarah Staudt

For the first time in over a decade, prison and jail populations increased [[link removed]] in 2022, and state prison systems and the federal Bureau of Prisons are predicting future growth. Although there are many reasons for this — including courts returning to normal operations after the height of the pandemic — at least some of this expected rise will be the direct result of regressive policy choices made by state legislatures.

The politics we have seen surrounding crime and punishment are eerily reminiscent of 1990s “tough on crime” rhetoric: in Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis suggested that his political opponents are “ pro-crime [[link removed]],” throughout the country; while Democrats [[link removed]] attacked [[link removed]] parole reform, reform-minded prosecutors, and bail reform in their 2022 mid-term election challenges. This rhetoric contradicts the facts: crime across the nation remains at record low levels, including a likely dramatic decrease [[link removed]] in violent crime in 2023.

As our partner organizations around the country decry this resurrection of bad policy, we looked at recent legislation passed around the country to identify trends in this most recent crop of throwback laws. In this briefing, we present some of the most common kinds of tough-on-crime laws passed in 2023 and the best arguments against them, so that advocates can be ready if these trends appear in their state.

Renewing the War on Drugs

In recent years, substantial progress has been made to address and begin to reverse the harmful policies [[link removed]] from the War on Drugs. The authors of these policies, passed between the 1970s and 2010s, created draconian mandatory minimum sentencing laws, established a racist sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine, and led to the incarceration of millions of people. Despite spending billions [[link removed]] each year to enforce these policies, the drug war has not reduced drug use [[link removed]] rates, drug prices have dropped, and overdose deaths have [[link removed]] risen [[link removed]]. Based on our experience with the Drug War, there is no reason to think that arrest and incarceration can stop drug use or trade.

Fentanyl now permeates [[link removed]] the United States drug market, leading to higher risks of overdose. Experts and advocates consistently urge a public health approach to fentanyl, but, unfortunately, too many states are treating it as “ Crack 2.0 [[link removed]]”, pursuing the same failed policies that sent millions of people to prison. This includes penalty enhancements for both possession and distribution of fentanyl and increased penalties for homicide charges leveled against people who provide drugs to a person who subsequently dies of an accidental overdose — often called “drug-induced homicide” laws. These laws are often levied against people using drugs together, who may or may not know that fentanyl is present in what they are using.

This year, a number of states passed laws resurrecting failed war on drugs policies:

Alabama [[link removed]] (HB 1) created mandatory minimums for possession of fentanyl. This bill was especially concerning because it passed the legislature unanimously, suggesting that there was no meaningful debate about whether the policy would be effective. Iowa [[link removed]] (HB 595) increased penalties for both possession and distribution of fentanyl. Wisconsin [[link removed]] (AB 68) increased penalties to 60 years for reckless homicide involving delivering fatal drugs. The law would apply to people using drugs together.

Arizona [[link removed]] and the federal government have also come close to passing retrograde drug legislation. Arizona’s legislature passed a presumptive 10 year mandatory minimum sentence for possession of as little as 2 milligrams of fentanyl; that bill was vetoed by the governor. At the federal level, the HALT Act [[link removed]]would trigger new and increased mandatory minimum sentences for fentanyl; it has passed the House and currently sits in the Senate.

Fighting back against zombie drug policies

Advocates facing regressive drug policy changes have the benefit of decades of research [[link removed]] showing that these policies do not work, have never worked, and cause massive harm to communities.

First, advocates can rely on the mountain of evidence showing mandatory minimums and longer prison terms do not reduce crime, drug use, or overdoses. Families Against Mandatory Minimums has compiled a wealth of resources on sentencing reform [[link removed]], including a handy guide [[link removed]] to arguments against mandatory minimums. They argue that mandatory minimums create racially biased outcomes — Black people are 65% more likely to face mandatory minimum charges. Advocates can also point to the ways that lengthening prison sentences will expand prison populations in the long run.

Second, advocates can educate lawmakers on how carceral approaches fail to address the fentanyl crisis. In particular, many lawmakers believe that jails and prisons will provide treatment for opioid users — in fact, incarceration increases overdose risk, and few people receive treatment inside. Policymakers also believe they can target drug dealers with harsh penalties without harming people who use drugs. In fact, drug users and drug suppliers are most often the same people [[link removed]]; sentencing enhancements are unlikely to affect so-called drug “kingpins” and will more likely target users and low-level sellers. Drug Policy Alliance has a great video [[link removed]] on this subject.

Lastly, advocates can provide lawmakers with alternatives to these carceral policies. Kneejerk penalty increases are often the product of a desire to “do something” about the very real devastation that fentanyl and overdoses are wreaking in communities across the country. But doing things differently during this overdose crisis means taking a public health approach to drug use. Drug Policy Alliance has created a comprehensive toolkit [[link removed]] on such health-centered approaches, including increasing access to treatment and harm reduction approaches like safe consumption sites and fentanyl test strips.

Criminalizing the homeless

The United States has a long history [[link removed]] of responding to the problem of homelessness with criminalization and punishment. Homelessness has risen [[link removed]] in recent years, driven by economic factors like increased housing costs, as well as by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As concern about homelessness rises, some jurisdictions are trying to criminalize their way out of a problem that can only be addressed with social services and housing.

In Georgia [[link removed]](SB 62), the state legislature passed a law requiring that municipalities enforce anti-camping laws. Alabama [[link removed]] (HB 24) expanded the definition of loitering to encompass more unhoused people.

Arizona [[link removed]] also came disturbingly close to passing similar policies. A vetoed bill in Arizona (SB 1024) would have created an anti-camping law, and two other bills proposed further criminalized homeless encampments but failed.

There are dozens of ways that policymakers have targeted people experiencing homelessness. In 2021, the National Homelessness Law Center published a guide [[link removed]] to laws around the country criminalizing homelessness; they note that as of 2021, almost every state has at least one law restricting behaviors associated with the experience of being homeless.

Protecting unhoused people from backwards policies

There’s no denying that rising housing insecurity is a genuine concern. Unfortunately, the solutions are complex, and can’t be solved by simply outlawing living outside. Advocates can help lawmakers understand the feedback loop [[link removed]] between criminalizing homelessness and increasing mass incarceration. Further criminalizing homelessness is likely to increase jail populations — and jails are ill-equipped to address the poverty, mental health, and substance use related reasons why people are experiencing homelessness. The National Homeless Law Center’s comprehensive guide notes that criminalization harms the health and wellbeing of unhoused people, and is an extremely expensive reaction to homelessness. Incarcerating someone costs over $47,000 [[link removed]] a year; a week in a jail cell might cost the equivalent of a month or more of housing.

Advocates can also help lawmakers find and implement successful, humane, and non-carceral approaches to this crisis. “Housing First” policies [[link removed]], which give people housing as the first step in holistically addressing their challenges, have been shown to interrupt cycles of criminalization and give people a path to long-term, stable housing. Housing First is part of a suite of innovative approaches to homelessness cataloged by the National Homelessness Law Center; other approaches include expanding access to affordable housing subsidies, embracing innovative housing solutions like “tiny home” communities, and preventing homelessness before it happens by reforming eviction laws and prohibiting discriminatory housing policies.

Lastly, the Homelessness Law Center notes that some policies criminalizing homelessness violate constitutional rights, and can be challenged in the courts [[link removed]]. The Ninth Circuit has ruled that imposing criminal penalties for people who cannot obtain shelter violates the Eighth Amendment [[link removed]] prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. Sweeps of tent cities [[link removed]] have been found to violate due process rights when governments destroy or confiscate personal property without notice. The courts may provide another avenue for protecting the basic human rights of people experiencing homelessness

Resurrecting failed sentencing policies

2023 saw a resurgence of so-called “Truth in Sentencing” laws. In the 1990s, federal legislation established funding incentives [[link removed].] that encouraged states to pass laws requiring that people charged with certain offenses serve at least 85% of their sentences in prison. In the mid- to late 90s, 21 states passed these laws. These policies sometimes as much as doubled [[link removed]] people’s actual prison terms overnight, as states that had historically allowed people access to parole after half or less of their sentences were suddenly requiring much more time in custody before parole. Notably, these sentencing structures reduce the ability of people to earn time off their sentences for good behavior or for completing programming, and therefore remove powerful incentives that support prison safety and reentry success. In 2022 and 2023:

Louisiana [[link removed]] (HB 70) reduced the ability of people convicted of repeated non-violent offenses to earn time off their sentence for good behavior. South Dakota [[link removed]] (SB 146) eliminated parole eligibility for many offenses and reduced the ability to earn sentencing credit. Arkansas [[link removed]] (SB 495) changed sentence structures and made certain felonies ineligible for sentence credits.

In 2022, Tennessee’s [[link removed]] SB 2248 served as a cautionary tale. Tennessee’s Department of Corrections projects that the resulting increases in incarceration will cost taxpayers at least $40 million over the next 8 years. Chillingly, when asked about these costs, the Speaker of the House simply said [[link removed]], “if we need to build more prisons, we can.”

The truth about “Truth in Sentencing”

Because Truth in Sentencing has been tried before, advocates have lots of resources showing that it is a failed and counterproductive policy. Research consistently shows no public safety benefit [[link removed]] to increased incarceration, and that longer sentences do not deter [[link removed]] crime. Research also shows that Truth in Sentencing reduces incentives [[link removed]] for incarcerated people to complete rehabilitative programming, increases safety risks for people in prison and corrections officers, and increases recidivism. Truth in Sentencing leads directly to prison overcrowding, which causes immense suffering.

Truth in Sentencing and other “tough-on-crime” policies are often enacted in the name of crime victims. Advocates can help policymakers understand that most victims of violence prefer [[link removed]] that money be spent on violence prevention, not incarceration.

Lastly, because of the immense expense of Truth in Sentencing policies, progressive advocates may find unlikely bedfellows in the fight against these laws. In Tennessee, the American Conservative Union opposed [[link removed]] the Truth in Sentencing bill; voices on both sides of the aisle understand that investing in prisons is an ineffective, wasteful, and dangerous approach to public safety.

Building more prisons

States continue to invest hundreds of millions of dollars into building new prisons instead of pursuing decarceration strategies. These efforts often cite prison overcrowding or aging buildings to justify this immense expenditure — but fail to explore proven strategies to reduce the number of people behind bars. In 2023, states made major moves towards prison construction:

Arkansas [[link removed]] (SB 495) appropriated $470 million for 3,000 new prison beds. South Dakota [[link removed]] (HB 1016) appropriated $60 million for a new women’s prison and $340 million for a new men’s state prison. Montana [[link removed]] (HB 817) appropriated $211 million for capital improvements at Montana state prisons. Combatting prison construction

Demands for new or expanded prison construction are constant features of the criminal legal reform landscape. Often, these efforts are sold to lawmakers as either necessary or actually progressive, when in fact they are neither. Although it may be true that prison buildings are aging and that prisons are overcrowded, the most straightforward — and most cost-effective — approach to addressing these problems is decarceration. Substantially reducing prison populations can allow states to close decrepit buildings instead of spending millions renovating or rebuilding them. Around the country, states have successfully reduced their prison populations enough to close facilities; twenty-one states fully or partially closed [[link removed]] prisons between 2000 and 2022.

Advocates arguing against prison construction can look to the detailed [[link removed]] plans [[link removed]] created by activists to close 10 prisons in California by 2025. They may also find the Prison Policy Initiative’s anti-jail expansion [[link removed]] materials helpful — many of the arguments against building new jails also translate to the prison context. Even in states where active plans to build prisons are not on the table, advocates can argue for prison and jail construction moratoriums [[link removed]], which can give state policymakers time and space to genuinely pursue decarceral solutions, instead of investing in our failed mass incarceration system.

Undermining reform prosecutors

In recent years, many jurisdictions have elected reform-minded prosecutors (sometimes called “progressive prosecutors”) who are interested in changing the tough-on-crime policies behind mass incarceration. The American criminal legal system is designed to give substantial discretionary power to prosecutors, and prosecutors are increasingly using this discretion to roll back some of the most damaging parts of the system. These prosecutors have taken a range of approaches, from increasing access to diversion programs to creating conviction integrity units that examine the cases of incarcerated people asserting their innocence. Although some reform prosecutors have seen pushback from voters in recent years, most still enjoy widespread support.

Unfortunately, conservative state legislatures continue to try to undermine [[link removed]] these democratically elected local officials with legislation designed to take their discretionary power away and force them to adhere to carceral policies — or risk being removed from office.

Florida Governor DeSantis has continued a trend of removing popular States Attorneys [[link removed]] — including the state’s only Black woman state prosecutor — because of complaints about sentencing decisions and statements opposing his attacks on reproductive rights and gender-affirming health care. In Georgia [[link removed]] (HB 231), the state legislature created a “Prosecuting Attorneys Oversight Commission” empowered to investigate and remove local prosecutors. In Texas [[link removed]] (HB 17), the legislature passed a bill allowing courts to remove district attorneys for failing to pursue certain types of prosecutions. Protecting local control of prosecutions

Advocates can help policymakers and the media understand that state legislative efforts like these undermine local elections and reduce confidence in the democratic process. Although rhetoric against reform prosecutors has been loud and sometimes extreme, it can be helpful to point to evidence that Americans are still broadly supportive [[link removed]] of criminal legal system reform, and continue to support it at the polls. Reform prosecutor races are often high profile and hard-fought, and voters have made a clear and intentional choice to go against the status quo of harsh criminal legal system policies. Those choices should be respected.

Importantly, there is no evidence that crime has worsened [[link removed]] under reform prosecutors. In fact, between 2015 and 2019, cities with reform prosecutors were less likely to experience a rise in homicides than those with traditional prosecutors.

Conclusion

We unfortunately couldn’t possibly cover all of the “zombie policies” cropping up around the country. Other notable examples include bills to enshrine cash bail more deeply in state law ( Wisconsin [[link removed]]), and expanding the use of non-unanimous jury verdicts for the death penalty ( Florida [[link removed]]), among many others. And by highlighting these setbacks, we don’t intend to diminish the real progress made around the country in 2023. Our Winnable Battles [[link removed]] report details some of these successes; the Sentencing Project’s [[link removed]] roundup of 2023 trends in criminal legal system reform highlights even more.

But the forces that seek to entrench and expand mass incarceration remain active across the country. We hope that this guide helps arm advocates with some of the arguments they need to avoid history repeating itself.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: 32 reforms to the criminal legal system ripe for victory in 2024 [[link removed]]

With lawmakers across the country starting their 2024 legislative sessions, we've got 32 proven policies [[link removed]] to shrink the size of the carceral system, promote public safety, and take action on racial inequities in the system.

Why did prison and jail populations grow in 2022 — and what comes next? [[link removed]]

Recently published data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics show growing prison and jail populations.

In this recent briefing [[link removed]], we explain this growth has little to do with changes in crime. Instead, the trend reflects court systems’ slow return to “business as usual” and lawmakers’ resurrection of ineffective “tough on crime” strategies.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor