| From | Reveal <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Kids on the Line: What it means to be Latinx in the wake of the El Paso shooting |

| Date | August 8, 2019 10:35 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

News that the El Paso shooter had written a manifesto against the “Hispanic invasion of Texas” sent ripples of fear and anxiety among the Latinx community ([link removed]) .

It’s not the first time Latinx residents have felt apprehension about their place in the U.S. since President Donald Trump launched his presidential campaign by calling Mexicans drug dealers and rapists. Some studies suggest ([link removed]) that many who identify as Latinx have experienced an increase in stress, anxiety and cardiovascular issues since the election.

This week, our reporter Aura Bogado asked on Twitter: “Latinxs: how do you feel in public right now? What do you think about? Is there anything you've visibly or verbally changed, and if so, why?”

She’s received hundreds of replies. Here are some of the responses:

* “I’ve become hyper-aware of when I’m in almost all-white spaces & do internal calculations of what that means for my safety or well-being in different ways (physical & emotional). It’s honestly very exhausting & draining.”

* “I make it a point to speak Spanish in public more. I’m here. I’ve been here all my life. My family speaks more than one language. We call two countries home. I’m proud of that fact, and I will not be scared into isolation.”

* “My mom calls me routinely to remind me to carry around my ID everywhere (even though I’m a citizen), and now I imagine she’ll also start telling me to keep an eye on my surroundings. At any rate, I’ve started wondering how sustainable my existence here is. Will it only get worse?”

* “I’ve rehearsed what I would do and say if someone pulls a ‘Go back to your country’ on me, especially if I’m with my parents. I’m pretty lucky to live in a predominantly Latinx community, but you just never know.”

Read the Twitter thread here. ([link removed])

AN UPDATE ON THE GOVERNMENT’S SHELTERS FOR MIGRANT CHILDREN

Last week, we brought ([link removed]) you the story ([link removed]) about the government’s plan to place migrant children in shelters with little experience and troubling track records.

The plan is part of the government’s efforts to expand its network of permanent shelters instead of relying on what are known as “influx facilities.” These shelters, like the tent city that sprang up in the Texas desert last year, are unlicensed and can house thousands of children at a time. Lawyers and advocates have widely criticized the Trump administration for keeping children in these makeshift shelters for months, sometimes without access to legal services. ([link removed])

Since our story was published, we’ve learned more about the government’s shelter expansion:

* Reveal investigative fellow Monique Madan recently reported ([link removed]) for the Miami Herald that the Trump administration moved children out of an influx facility in South Florida, the largest shelter for migrant children in the U.S. A refugee agency spokesperson told Monique that the bed capacity will be reduced from 2,700 to 1,200, to be used only “in the event of increased referrals or an emergency situation.” This news comes just two weeks after children at another influx shelter ([link removed]) were transferred out to other locations or released to sponsors.

* Last week, The Associated Press reported ([link removed]) that the government is looking for vacant properties in Florida, Virginia and Los Angeles to build permanent shelters by spring 2020. These shelters would be licensed, but as our Patrick Michels pointed out on Twitter, ([link removed]) they could still hold up to 500 children at a time.

Read Patrick’s Twitter thread here. ([link removed])

WHAT WE’RE READING

Frankie Madrid was 6 months old when his family came to the U.S. Twenty-six years later, he was deported to Mexico. (The California Sunday Magazine ([link removed]) )

He was self-conscious about his Spanish — he had learned it at home, speaking with his mom. In Mexico, people called this type of Spanish pocho — which also means a Mexican who has lost his culture — and family members would correct him. Sometimes they would speak too fast for him to understand, and there were moments he would just blurt out sentences in English. To distract himself, he binge-watched 13 Reasons Why, the Netflix series about a high school girl who leaves behind a box of cassettes that explain why she took her life.

He rented an apartment, a one bedroom in a lower-middle-class colonia north of downtown. It had a single window and a front door with bars. It looked like a little jail. With money from friends and family in Flagstaff — they had started a GoFundMe campaign — he bought a 2005 gold Nissan Altima. He could have used the money to pay someone to bring him back across the border, but he didn’t want to live his life always looking over his shoulder. If he was arrested, he would end up back in prison, and he never wanted to be there again.

One day, on his way to work, his car broke down, and he was stranded. Even though Flagstaff had a population of 72,000, Frankie always thought it felt like a small town. A stranger there would have come to his rescue. Hermosillo, which was ten times larger, was noisy and confusing, and passersby either ignored his appeals for help or told him to get out of the way.

More than 100 immigrants were pepper-sprayed at a detention facility after refusing to leave the recreational area. (BuzzFeed News ([link removed]) )

The inmates at Pine Prairie — where more than 1,000 ICE detainees can be held at a time — were pepper-sprayed after they demonstrated in the center’s yard, the source said. The inmates were then taken to a separate part of the facility to be decontaminated.

After this story was published, Bryan Cox, an ICE spokesman, confirmed the incident in an email to BuzzFeed News.

Cox said that a "group of ICE detainees refused to depart the outdoor recreation area at the Pine Prairie facility Friday evening."

"After repeated attempts by facility staff and ICE personnel to disperse the group and restore orderly operation of the facility, a brief, calculated use of pepper spray was employed Saturday morning."

In a Guatemalan village where many residents have left for the U.S., a family mourns the death of a boy who died at a U.S. hospital after crossing the border. (National Geographic ([link removed]) )

Agustín Gómez was struggling under a mountain of debt when he decided to leave his minuscule village in the misty highlands of Guatemala and take his 8-year-old son, Felipe, to America late last year. Ten days later, after crossing into Texas, Felipe fell sick with the flu and a bacterial infection. He was taken to a New Mexico hospital, and died shortly after being released. It was Christmas Eve.

Back in Guatemala, Felipe’s 22-year-old half-sister Catarina comforted her sobbing father over the phone and cooked hundreds of tortillas for the wake. “I’m glad you guys are together so you can mourn,” Agustín told her. “I’m all alone here.” As the news broke around the world, she watched the social media chatter. Commentators were saying that her family had used Felipe as a pawn to get into the U.S.; that poor people like them shouldn’t have kids.

Felipe’s death put a spotlight on the tiny town of Yalambojoch, nestled in a mountainous region called Huehuetenango that has been pushing residents toward the U.S. border at a rate unparalleled elsewhere in Guatemala. And Guatemala has quietly become one of the top senders of migrants to the U.S.

Your tips have been vital to our immigration coverage. Keep them coming: [email protected].

– Laura C. Morel

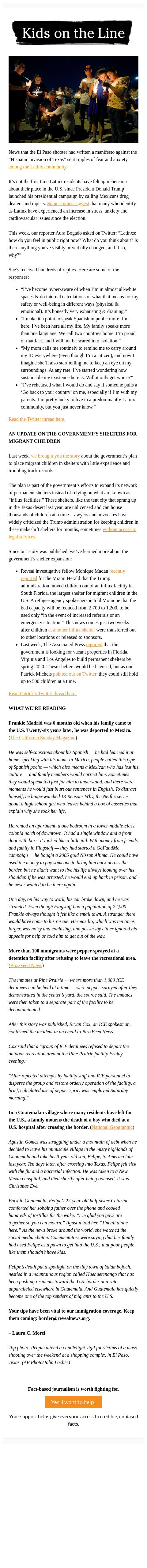

Top photo: People attend a candlelight vigil for victims of a mass shooting over the weekend at a shopping complex in El Paso, Texas. (AP Photo/John Locher)

Fact-based journalism is worth fighting for.

Yes, I want to help! ([link removed])

Your support helps give everyone access to credible, unbiased facts.

============================================================

This email was sent to [email protected] (mailto:[email protected])

why did I get this? ([link removed]) unsubscribe from this list ([link removed]) update subscription preferences ([link removed])

The Center for Investigative Reporting . 1400 65th St., Suite 200 . Emeryville, CA 94608 . USA

It’s not the first time Latinx residents have felt apprehension about their place in the U.S. since President Donald Trump launched his presidential campaign by calling Mexicans drug dealers and rapists. Some studies suggest ([link removed]) that many who identify as Latinx have experienced an increase in stress, anxiety and cardiovascular issues since the election.

This week, our reporter Aura Bogado asked on Twitter: “Latinxs: how do you feel in public right now? What do you think about? Is there anything you've visibly or verbally changed, and if so, why?”

She’s received hundreds of replies. Here are some of the responses:

* “I’ve become hyper-aware of when I’m in almost all-white spaces & do internal calculations of what that means for my safety or well-being in different ways (physical & emotional). It’s honestly very exhausting & draining.”

* “I make it a point to speak Spanish in public more. I’m here. I’ve been here all my life. My family speaks more than one language. We call two countries home. I’m proud of that fact, and I will not be scared into isolation.”

* “My mom calls me routinely to remind me to carry around my ID everywhere (even though I’m a citizen), and now I imagine she’ll also start telling me to keep an eye on my surroundings. At any rate, I’ve started wondering how sustainable my existence here is. Will it only get worse?”

* “I’ve rehearsed what I would do and say if someone pulls a ‘Go back to your country’ on me, especially if I’m with my parents. I’m pretty lucky to live in a predominantly Latinx community, but you just never know.”

Read the Twitter thread here. ([link removed])

AN UPDATE ON THE GOVERNMENT’S SHELTERS FOR MIGRANT CHILDREN

Last week, we brought ([link removed]) you the story ([link removed]) about the government’s plan to place migrant children in shelters with little experience and troubling track records.

The plan is part of the government’s efforts to expand its network of permanent shelters instead of relying on what are known as “influx facilities.” These shelters, like the tent city that sprang up in the Texas desert last year, are unlicensed and can house thousands of children at a time. Lawyers and advocates have widely criticized the Trump administration for keeping children in these makeshift shelters for months, sometimes without access to legal services. ([link removed])

Since our story was published, we’ve learned more about the government’s shelter expansion:

* Reveal investigative fellow Monique Madan recently reported ([link removed]) for the Miami Herald that the Trump administration moved children out of an influx facility in South Florida, the largest shelter for migrant children in the U.S. A refugee agency spokesperson told Monique that the bed capacity will be reduced from 2,700 to 1,200, to be used only “in the event of increased referrals or an emergency situation.” This news comes just two weeks after children at another influx shelter ([link removed]) were transferred out to other locations or released to sponsors.

* Last week, The Associated Press reported ([link removed]) that the government is looking for vacant properties in Florida, Virginia and Los Angeles to build permanent shelters by spring 2020. These shelters would be licensed, but as our Patrick Michels pointed out on Twitter, ([link removed]) they could still hold up to 500 children at a time.

Read Patrick’s Twitter thread here. ([link removed])

WHAT WE’RE READING

Frankie Madrid was 6 months old when his family came to the U.S. Twenty-six years later, he was deported to Mexico. (The California Sunday Magazine ([link removed]) )

He was self-conscious about his Spanish — he had learned it at home, speaking with his mom. In Mexico, people called this type of Spanish pocho — which also means a Mexican who has lost his culture — and family members would correct him. Sometimes they would speak too fast for him to understand, and there were moments he would just blurt out sentences in English. To distract himself, he binge-watched 13 Reasons Why, the Netflix series about a high school girl who leaves behind a box of cassettes that explain why she took her life.

He rented an apartment, a one bedroom in a lower-middle-class colonia north of downtown. It had a single window and a front door with bars. It looked like a little jail. With money from friends and family in Flagstaff — they had started a GoFundMe campaign — he bought a 2005 gold Nissan Altima. He could have used the money to pay someone to bring him back across the border, but he didn’t want to live his life always looking over his shoulder. If he was arrested, he would end up back in prison, and he never wanted to be there again.

One day, on his way to work, his car broke down, and he was stranded. Even though Flagstaff had a population of 72,000, Frankie always thought it felt like a small town. A stranger there would have come to his rescue. Hermosillo, which was ten times larger, was noisy and confusing, and passersby either ignored his appeals for help or told him to get out of the way.

More than 100 immigrants were pepper-sprayed at a detention facility after refusing to leave the recreational area. (BuzzFeed News ([link removed]) )

The inmates at Pine Prairie — where more than 1,000 ICE detainees can be held at a time — were pepper-sprayed after they demonstrated in the center’s yard, the source said. The inmates were then taken to a separate part of the facility to be decontaminated.

After this story was published, Bryan Cox, an ICE spokesman, confirmed the incident in an email to BuzzFeed News.

Cox said that a "group of ICE detainees refused to depart the outdoor recreation area at the Pine Prairie facility Friday evening."

"After repeated attempts by facility staff and ICE personnel to disperse the group and restore orderly operation of the facility, a brief, calculated use of pepper spray was employed Saturday morning."

In a Guatemalan village where many residents have left for the U.S., a family mourns the death of a boy who died at a U.S. hospital after crossing the border. (National Geographic ([link removed]) )

Agustín Gómez was struggling under a mountain of debt when he decided to leave his minuscule village in the misty highlands of Guatemala and take his 8-year-old son, Felipe, to America late last year. Ten days later, after crossing into Texas, Felipe fell sick with the flu and a bacterial infection. He was taken to a New Mexico hospital, and died shortly after being released. It was Christmas Eve.

Back in Guatemala, Felipe’s 22-year-old half-sister Catarina comforted her sobbing father over the phone and cooked hundreds of tortillas for the wake. “I’m glad you guys are together so you can mourn,” Agustín told her. “I’m all alone here.” As the news broke around the world, she watched the social media chatter. Commentators were saying that her family had used Felipe as a pawn to get into the U.S.; that poor people like them shouldn’t have kids.

Felipe’s death put a spotlight on the tiny town of Yalambojoch, nestled in a mountainous region called Huehuetenango that has been pushing residents toward the U.S. border at a rate unparalleled elsewhere in Guatemala. And Guatemala has quietly become one of the top senders of migrants to the U.S.

Your tips have been vital to our immigration coverage. Keep them coming: [email protected].

– Laura C. Morel

Top photo: People attend a candlelight vigil for victims of a mass shooting over the weekend at a shopping complex in El Paso, Texas. (AP Photo/John Locher)

Fact-based journalism is worth fighting for.

Yes, I want to help! ([link removed])

Your support helps give everyone access to credible, unbiased facts.

============================================================

This email was sent to [email protected] (mailto:[email protected])

why did I get this? ([link removed]) unsubscribe from this list ([link removed]) update subscription preferences ([link removed])

The Center for Investigative Reporting . 1400 65th St., Suite 200 . Emeryville, CA 94608 . USA

Message Analysis

- Sender: Reveal News

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- MailChimp