|

|

Can We Build a Department Store for the 21st Century?

The steep decline of the great American department store represents a great loss to consumers and society at large. But it can be reversed—with the right changes

At its peak, the large urban department store was like a center of the American universe. From the late 19th century to about 1970, these stores were major tourist attractions, drew huge crowds, sat at the core of public transportation systems, offered fashion shows and community events, and had spectacular buildings.

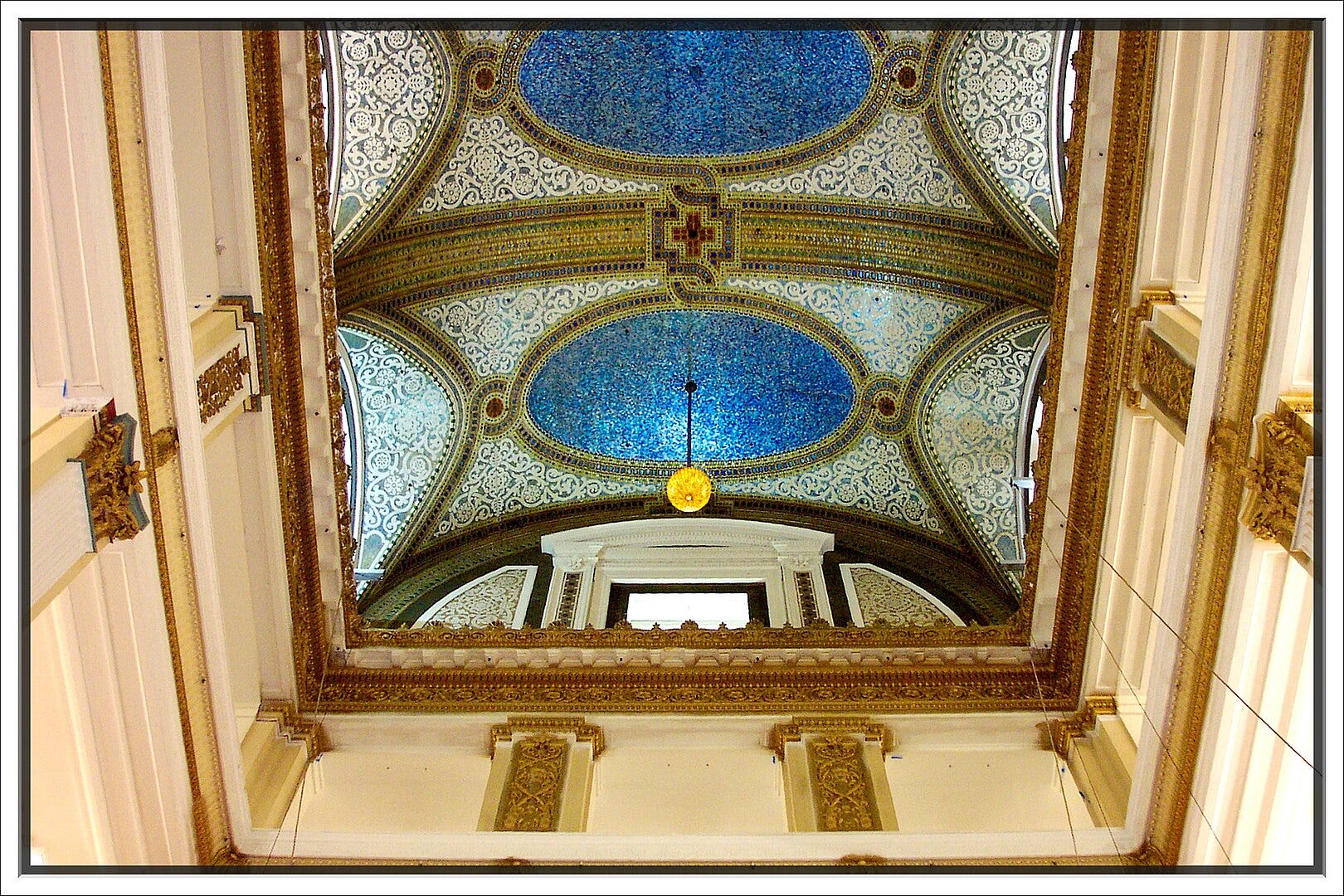

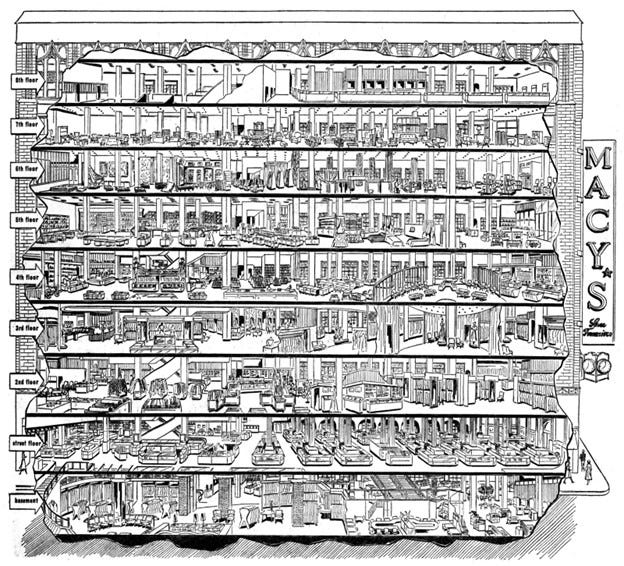

Today, it’s almost hard to fathom the grandeur of these stores: They were not just places to obtain all manner of goods, but they were showpieces themselves. The giant Marshall Field’s store on State Street in Chicago had (and still has) the largest Tiffany glass mosaic in the world, made up of 1.6 million tiles covering 6,000 square feet. The 50-foot Ionic columns on the storefront are excelled only by those in ancient Egypt. Macy’s Herald Square in Manhattan drew tens of thousands to the 1902 grand opening of its 57-acre facility, 14 times the size of the average Walmart Supercenter. Initial sales at that Macy’s were the equivalent of $560 million a year in 2023 dollars, and by 1930, that number was up to $1.8 billion.

Over the last 40 years, Macy’s has acquired almost every major department store in the country, leaving only Nordstrom, Dillard’s, Belk and Boscov’s to survive as independent companies. Macy’s stores are present in almost every major American city—unlike Walmart, which is not in the nation’s largest retail center, Manhattan. Each of those stores is in a highly visible, convenient location—everyone knows where their local Macy’s is.

But how the mighty have fallen. Macy’s stock fell from a peak of about $70 a share in July 2015 to a low of under $5 in the early days of the COVID pandemic. Just weeks ago, one private investor group proposed a buyout of all Macy’s stock it does not already own for $21 a share—a buyout bid totaling $5.8 billion. However, Macy’s real estate alone might be worth more than that (analysts believe, for example, that the value of just the Herald Square location may be worth $900 million or more). This implies that Macy’s retail operation itself is considered virtually worthless. Given the role that Macy’s and other department stores have played in shaping the American retail experience, their decline is truly stunning and sad.

Decline… and Opportunity

I started dreaming up what an ideal department store would look like when I was 12, in 1963. I first fell in love with the great department stores after visiting them as a child with my family: L.S. Ayres in Indianapolis, Famous-Barr in St. Louis, Marshall Field’s in Chicago. I ended up analyzing the department store industry for Citibank in the early 1970s, and by the late 1970s, I worked for Federated Department Stores as a buyer and then May Department Stores as a competitor analyst and mergers and acquisitions researcher.

My love for these large stores was one of the inspirations that led me to found my initial startup—Bookstop, the first chain of giant book superstores. Throughout my career, I’ve visited more than 40 countries, and I’ve loved checking out department stores everywhere I’ve gone.

As someone with a passion for the department store industry, I’ve found its present state to be particularly distressing. But I don’t believe all is lost: There are opportunities to create stores that come closer to what shoppers experienced in the department stores’ glory days.

When I worked for the big department store companies, I could see the beginnings of their decline. Originally, stores like Macy’s carried everything imaginable—even hardware, appliances, pets and giant book departments. Each store in a city had a unique personality, often highlighted by restaurants with great food.

Over time, department stores became more like large apparel stores, as they pursued the category with the highest gross profit margins (the percentage spread between what they paid for merchandise and what they sold it for). Yet, over the last 40 years, apparel has not grown as fast as the categories they abandoned—consumer electronics, books, sporting goods, stationery and office supplies, auto parts, pets, toys and games, gourmet foods and even household appliances. Walmart and Target didn’t give up on these areas, instead expanding these departments.

Today, Target and Walmart are the true department stores for American shoppers, with no full general merchandise store “above them” in terms of product quality, uniqueness or variety. Target, which was founded by the department store company Dayton-Hudson, now generates more annual revenues than all the traditional department stores in America combined. And Walmart does six times the revenue of Target, ample evidence that Americans still love their true department stores.

At the same time that the department stores chose to focus on apparel and accessories, they began to all look alike. They often underinvested in remodeling. Department stores today look remarkably like those of the 1970s and 1980s. The department stores’ exclusive emphasis on fashion was also challenged by the extraordinary growth of apparel discounters like T.J. Maxx and category specialists such as Dick’s Sporting Goods and Ulta Beauty.

How engaging is the present Macy’s to the typical man or child? How excited are Gen X, Y and Z to visit a Macy’s store?

A Plan for the 21st Century Department Store

Designing a department store for the 21st century may be difficult, but it’s certainly not impossible. Here’s how I’d go about doing it:

Study up. As with any big challenge, you’ve got to do your homework before you try to take it on. You can’t expect to solve a problem without the context you need to avoid pitfalls and make a plan that will have a greater chance of success.

First, look at some of the top department stores around the world: El Corte Inglés Barcelona, Selfridges London, El Palacio de Hierro Polanco in Mexico City and Tokyo’s Seibu Ikebukuro. While some of them are also stumbling in the face of competition, many have elements unfamiliar to American consumers, such as expansive food courts.

You can also look stateside for examples of what to do and what not to do. Study the strongest and weakest departments at Walmart and Target, and be aware of the strengths of Marshalls, Ross, T.J. Maxx, Burlington and even Costco. And of course, look at online retailers: Study Amazon and eBay, and look at their ratings and number of ratings, in every category under consideration. Focus on the items and categories that are “trending”—rising in sales.

The world of data also provides a rich mine of information needed to strengthen a plan for a 21st century department store. Were I advising Macy’s on how to update for the modern era, I’d urge them to look at the Economic Census data on merchandise line sales by store type, along with the company’s internal data, to get a clear idea of the categories in which Macy’s has lost the most market share, and to which competitors that share was lost.

What about consumers? I’d recommend studying the spending habits of people between the ages of 12 and 35, and the trends in their preferences, since those are the customers you will be serving in coming decades. Take a hard look at their lives in general, which movies they watch, books they read, social media they use, cars they drive. Review the most popular and growing college majors.

Survey current customers and non-customers—preferably not online, where facial expressions, voice intonations and gestures remain unseen and unheard. Use focus groups but pay primary attention to aggregate numbers. Figure out who the company’s customers were 40 years ago, which ones were lost, why and to which competitors. Who is most likely to return? Which new groups might you appeal to?

Don’t forget to look to the past. Many of the best ideas come from Macy’s glory days: Some of the basic principles applied by the Straus family, which acquired Macy’s in the late 19th century and operated it for the next several decades, are timeless. Read the books on Macy’s history by Ralph Hower, Edward Hungerford and Robert Grippo. Meditate on the images in Jan Whitaker’s “The World of Department Stores.”

Look back at store directories from the halcyon days of the big department stores: What are the equivalents of those departments today? What now serves the cultural needs they served? If customers no longer spend as much time sewing, for example, what are they spending that time on?

Finally, there are plenty of creative ideas that may be gleaned from the world of entertainment. Study the best interactive museums thoroughly: Look at their use of large digital graphics and interactive displays, and study how consumers use and relate to them. Also, take a hard look at Disney World and other entertainment venues—Las Vegas, even the Singapore and Dubai airports—for their overall feel and sense of excitement.

Put your research to the test—and don’t be afraid to take risks. After spending a year doing the above research, it’s time for action: Evaluate your findings and incorporate the best learnings into a test store. Take a strong suburban Macy’s in a growing market—a typical 260,000-square-foot store, which is about 40% larger than a typical Walmart Supercenter. It would be smart to open such a test store in October, leading into the busy holiday shopping season.

In opening such a store, strike a balance between staying close to your core business while also testing the boundaries of what your new store can do and provide to customers. To do that, you must set low expectations and be willing to risk substantial funds for this test: Project a substantial drop in sales (due to losing some lines of business) and an increase in expenses, plus a substantial budget for remodeling and doing the basic groundwork, such as hiring specialists in new areas of business. Consider this investment as R&D, as any great tech company would.

This new department store should focus in part on what the company does best, and that will require shedding lines of business. But which lines of business should be kept, and which should be shed? Look at the company’s best customers—the ones who spend the most. Keep those departments in which those customers spend money. Keep core apparel areas and highlight cosmetics, currently a strong category where Ulta and Sephora have taken business that used to be the province of department stores. Increase the space, staff and selection, and do vendor partnership and boutique deals in these core areas, but do not abdicate your responsibility to be the customer’s agent, as has become too common in the industry.

Say that this newly designed store preserves 140,000 square feet for those core areas the company wants to keep—the apparel, the cosmetics and so on. That would free up 120,000 square feet for new departments. What should fill that space? List the possibilities for new departments, keeping younger demographics in mind, since they will hopefully be your customers long into the future. Some areas to consider include board games, electric bikes or small electric and hybrid vehicles, athletic footwear, pet-related merchandise, vinyl records, appropriate sporting goods like pickleball equipment, fitness products, electronics, and coffee and tea.

Peruse Kickstarter and Shark Tank to see hot new ideas, as well as the websites that report on new products and gadgets. Study Five Below, pOpshelf, and Asian-based chains like Miniso, Daiso and Mijyi that focus on small, affordable, unique products.

Seek categories that increase frequency of visits—what items are your customers buying every week? Keep in mind that services and experiences are the future, as “goods” comprise a continuously shrinking share of consumer spending. Food service is key, as the restaurant industry continues its century-long rise.

The prospect of new departments opens the door to thinking outside the box. Here are a few possibilities that come to mind:

Consider organizing some departments or boutiques around topics or lifestyle issues rather than conforming to traditional product categories. A gift area, a cooking area (housewares, cookbooks), a history or nostalgia area (collectibles, antiques, rare books), a creativity corner (musical instruments, art supplies, crafting), or a “recycled” zone (“pre-owned” clothes, books, collectibles, vinyl records). Even if you can’t build a full food emporium, perhaps a great wine and cheese department might work well.

Look into creating bundles available nowhere else, as Costco sometimes does. How about a bundle of Bill Gates’ 10 favorite books, or a laptop or tablet pre-loaded with fashion apps and software, or with art and music creativity software? Bundle luggage with the right apparel for vacation season, perhaps with a cruise travel agency.

Think about incorporating a geographical approach—say, an Italy boutique, a France boutique, as well as Morocco, Thailand, Scandinavia and Latin America. Fully developed, such departments might include food, apparel, decorative home goods, even books and music.

Consider leasing store space to outside retailers. Macy’s currently leases over 14,000 square feet in its Herald Square location to Toys “R” Us for a pop-up store, and it has opened similar Toys “R” Us pop-ups in other Macy’s stores. One could imagine Macy’s leasing space to Barnes & Noble for a “bookstore-within-a-store.” And this leased department model can apply to services as well: Food service (both onsite and to-go), tailoring and seamstress services, hair salons and optical goods are just a few services that might work to draw new (and old) customers into the store.

Remember that presentation matters and incorporate that into your plan. That brings me to my next recommendation: Bringing customers into a store is important, but keeping them there matters as well. And to do that, you have to make them want to stay. The amount, variety and quality of merchandise matter a great deal, but the environment and ambience matter, too.

How can the 21st century department store put its best foot forward from a presentation perspective? First, apply what was seen in the museums, Disney, Vegas and overseas stores to every department—think huge wall videos, supergraphics and interactivity. Selectively use mobile price-checking, directory stands and signs, and automated checkouts, but ensure these are thoroughly tested and do not annoy customers.

Technology isn’t the only thing that has to work well: Overstaff the store with well-trained humans, seeking out the most service-oriented people you can find. Above all else, make the customer experience faster, easier and more convenient. Don’t put up hurdles to transactions. Accept PayPal, the new short-term payment platforms and the like. Let customers use all their in-store time for browsing and shopping, not boring transactional steps.

Bring back a more carnival-like atmosphere, which the department stores of old had. Imagine lots of sampling, lots of opportunities to try the products. An in-store theater could show films or programs that relate to themes in the store—and also keep people in the store longer. Special store events can help set this store apart as well—from contests and raffles to celebrity in-store appearances and live music.

It is especially important to have a potent launch—heavy advertising leading up to a celebratory grand opening. But not just with standard promotions—make news by giving away cars, flying hot air balloons, shining searchlights at night, even hiring airplanes towing banners—whatever makes people (and the press) sit up and take notice.

Equally important, capture customer reactions. Offer a discount to any customer who answers a survey. Offer more for those who will join a focus group.

In short, the 21st century department store should bring energy to everything it does—and make customers feel it and want to be a part of it. Rather than a quick, utilitarian stop to run a quick errand, the department store ought to revert to its past glory as a destination, a place where you could spend hours.

Give this experiment time to work—and change what you need to. This test store must be given adequate time to operate in order to draw conclusions about its success. I’d recommend operating such a store for at least 12 months—including at least two holiday seasons—before making those judgments. During that period, study every expense, every capital investment, every detail. Then develop a phase two prototype based on what worked and what didn’t, and try it in two or three more stores for a year.

By phase three, be ready to revamp the entire company. And remember that the research part of this plan must go on: Continue the studies listed earlier, keeping up with changing customer trends and what the most successful museums, tourist attractions and international retailers are doing.

More than ever, customers face an intensely competitive world for their attention. The department store has lost its way in the retail world over the past few decades, but it still has a unique part to play—and one that can grow if the department store industry makes the right changes. These changes must combine looking back with looking ahead—part recollection of the department stores’ gloried past, part reinvention of what these stores can achieve in the 21st century.

You’re currently a free subscriber to Discourse .