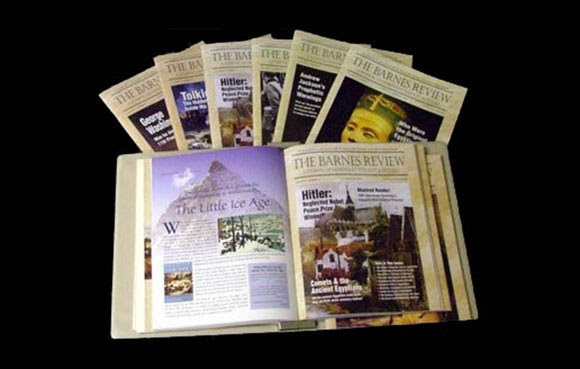

The article below is a sample of the best of The Barnes Review magazine. Please consider susbscribing to the magazine by clicking here.

The Mysterious Death of Meriwether Lewis

espite establishment claims of suicide, the preponderance of the evidence seems to be that famed American explorer Meriwether Lewis was murdered. Who did it, and why? According to the book The Suppressed History of America: The Death of Meriwether Lewis and the Mysterious Discoveries of the Lewis & Clark Expedition* by Paul Schrag and

Xaviant Haze, parts of Lewis’s journals are strangely missing. Were they destroyed as part of a cover-up? Did Lewis know too much? Was he getting ready to spill the beans on certain things he found during his travels—things the establishment, including the Smithsonian Institution, wanted hidden? What was it he discovered that would have warranted his murder? Was he owed money that the U.S. government didn’t want to pay him? Did he have a political future—or did he, very simply, die by his own hand?

By Philip Rife

Meriwether Lewis was one of this country’s first national celebrities. As half of the famous exploring team of “Lewis and Clark,” he opened a window to the vast territory between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean acquired from France in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The pair’s epic three-year adventure inspired countless fellow citizens of the young republic to head westward.

In 1809, the 35-year-old Lewis was serving a new role as governor of the Louisiana Territory when he undertook a trip to the nation’s capital. But he never reached Washington. While stopped for the night at a small inn (called Grinder’s Stand, after its owner, Robert Grinder) along the Natchez Trace in Tennessee, he suffered one or more wounds that proved fatal. (There are major discrepancies in contemporary accounts regarding the number, location and type of injuries, including: whether there was/were one or two bullet wounds; if he was shot in the forehead, back of the head, under the chin, in the side, in the chest, in the stomach or in the back; and whether he had knife or razor wounds from head to toe.)

KNOWN Events at the time of the crime

There’s even greater disagreement about whether Lewis’s wounds were self-inflicted or delivered by someone else. During the night, when the innkeeper was supposedly on a farm 20 miles away, the innkeeper’s wife said she heard two gunshots from the direction of the separate cabin occupied by Lewis, but she waited until daylight to investigate. When she did, she reportedly found the governor lying on the floor with an apparent bullet wound in his left side. Lewis was barely alive. The woman said the only words he spoke before he died were: “I am no coward, but it is hard to die.”

Most historians subscribe to the theory that Lewis committed suicide. They offer a menu of possible reasons, among them: money problems, bipolar disorder, alcoholism, syphilis, a failed romance, drug addiction (from medicine containing opiates) and clinical depression.

Lewis’s traveling companion, James Neelly, broke the news to Lewis’s good friend and former president, Thomas Jefferson, in a letter: “It is with extreme pain that I have to inform you of the death of his excellency Meriwether Lewis, who died on the morning of the 11th, and I am sorry to say, by suicide.” Neelly later claimed that during the trip Lewis “appeared at times deranged in mind.”

Jefferson evidently accepted the suicide scenario, writing: “Gov. Lewis had, from early life, been subject to hypochondriac affections. It was a constitutional disposition in all the nearer branches of the family, and was inherited by him from his father. I observed at times sensible depressions of mind.” Lewis’s erstwhile partner William Clark was of a similar opinion: “I fear the waight [sic] of his mind has overcome him.”

Crewmen on the boat Lewis used for the first leg of his final trip supposedly reported he had attempted suicide twice while aboard. However, a letter attributed to the commander of the military outpost where the boat landed that described Lewis as suicidal has been declared a forgery by modern handwriting experts.

There are several indications Lewis had been shot by someone else. There was general agreement that there were no powder burns on his body, as would be expected if the fatal shot had been fired from close enough range for him to have held the weapon. By some accounts, the only firearm found in the death room was a rifle standing in a corner. Examination by other guests revealed it hadn’t been fired recently. There was reportedly no sign of the two pistols Lewis had been carrying.

A coroner’s jury returned a verdict of “death by suicide.” However, the jury foreman later said: “The jury were cowards and were afraid to bring a verdict of murder, which they knew was what they should have done. Someone said that the murderers had Indian blood in their veins, and they were afraid they would meet a similar fate.”

Finally, a doctor who examined Lewis’s remains in 1848, when they were re-interred under a memorial near the death scene, concluded, “He died by the hands of an assassin.”

If Meriwether Lewis’s death wasn’t a suicide, who might have had a motive for killing him? Several suspects have been put forward over the years.

One possibility is that Lewis was shot resisting a robber. The Old Natchez Trace—which runs from Natchez, Mississippi to Nashville, Tennessee—was notorious as a hunting ground for highwaymen. (Its nickname was the Devil’s Backbone.) Lewis was known to have been carrying $200 when he left for Washington (a small fortune in those days). Only 25 cents was found on his body. In addition, a gold watch he had with him on the trip reportedly later turned up in Louisiana.

Another possible motive may lie in the reason for his trip to Washington. In a letter to his famous travel companion William Clark, Lewis described the anti-corruption measures he planned to implement in the territory he governed: “It is my wish that every person who holds an appointment of profit or honor in that territory, and against whom sufficient proof of the infection of Burrism can be adduced, should be immediately dismissed from office without partiality, favor or affection, as I can never make any terms with traitors.”

Lewis was taking official and private papers to a committee of Congress investigating misconduct by the individual he had replaced as governor of the Louisiana Territory, a man named James Wilkinson. Wilkinson stood accused of abusing his office by selling favors and taking kickbacks. Lewis had also learned of Wilkinson’s involvement in a scheme with former Vice President Aaron Burr to set up an independent nation in what is now Kentucky and ally it with Spain. When details of the plan became known, Wilkinson turned on Burr, who was arrested and tried for treason. (Burr was eventually acquitted.)

Lewis may also have learned that Wilkinson had been spying for Spain for more than 20 years. (Among other things, Wilkinson provided the Spanish government with copies of Lewis and Clark’s confidential reports of their explorations.)

Besides Wilkinson himself, a number of his corrupt underlings when he was governor (some of whom continued to serve under Lewis) may have feared exposure and punishment. These include James Neelly, who was traveling to Washington with Lewis. At the time of Lewis’s death, Neelly was supposedly some 50 miles back on the trail rounding up two packhorses that had gotten loose and strayed off.

Frederick Bates, another Wilkinson ally who was an assistant to Lewis, hoped to replace Lewis as governor. He wasn’t along on the fatal trip, but a letter to Bates from his sister after Lewis’s death has led some to wonder if he may have hired someone to kill Lewis: “I lament his death on your account, thinking it might involve you in difficulty.”

It may just have been coincidental, but two years after Lewis’s death, the owner of the inn where the governor died purchased property said to have cost considerably more than his income as an innkeeper would seem to justify. Robert Grinder was charged with Lewis’s murder before a grand jury, but the case was dismissed for lack of evidence.

In light of all the inconsistencies surrounding Lewis’s death, his descendants petitioned the National Park Service twice to allow his remains to be exhumed for modern forensic analysis. Both requests were denied. A third request is currently being weighed by the Park Service.

Said one Lewis descendant (a retired U.S. Air Force colonel): “If I had to vote now, I’d vote it was murder. But the evidence is circumstantial. That’s why an exhumation and examination is so important.”

Sources:

American Heritage magazine, 10/2005.

Columbia magazine, fall 2004.

Chandler, David Leon, The Jefferson Conspiracies , 1994.

“Decoded,” History Channel, 2/8/2010.

Edwards, Frank, Strangest of All , Ace Books, New York, 1962.

George Mason University website.

Omaha (NE) World Herald , 1/23/2010.

Schrag, Paul, and Xaviant Haze, The Suppressed History of America , Bear & Co., Rochester, VT, 2011.

State Historical Society of North Dakota website.

Wilson, Colin and Damon Wilson, Unsolved Mysteries Past and Present , Contemporary Books, Chicago, 1992.

http://mail.americanfreepress.net/news/latest/index.php/campaigns/yq298agz91842/forward-friend/ny110xaj463f6

Remember: 10% off retail price for TBR subscribers. Use coupon code TBRSub10 if you are an active subscriber to claim your discount on books and other great products, excluding subscriptions.

Order online from the TBR Store using the links above or call 202-547-5586 or toll free 877-773-9077 Mon.-Thu. 9-5 ET with questions or to order by phone.

Know someone who might be interested in our books?

Forward this email to your friend by clicking here.

|