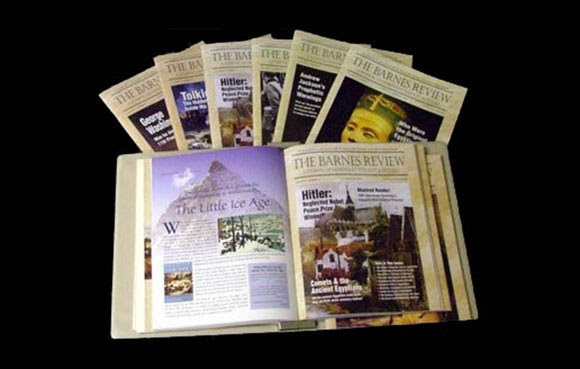

The article below is a sample of the best of The Barnes Review magazine. Please consider susbscribing to the magazine by clicking here.

TBR History Article - The Pounce on Prague - Czech Abuses Force Hitler’s Hand in Sudetenland

In 1938, the major powers of Europe and North America were extremely concerned about the developing situation in the artificially created state of Czechoslovakia. The Czechs had so abused the ethnically German inhabitants of Sudetenland, Hitler felt compelled to act to save his German brothers and sisters. War was seemingly avoided with the signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, but Poland decided it too wanted a piece of Czechoslovakia, as did Hungary. In addition, the Slovaks had no desire to be part of the amalgamated state of Czechoslovakia, throwing the whole situation into chaos. Hitler, concerned about violations of the rights of many of the ethnic groups living under Czech rule, moved into Prague and organized a large portion of Czechoslovakia into a German protectorate. While this might have been a smart move militarily, the author believes Hitler lost the moral high ground by forcing Slovaks, Moravians, Ruthenians etc to be subject to German rule without concern for their political self-determination.

By Joaquin Bochaca

Three hours after the signing of the Munich Agreement, 1 Poland sent an ultimatum to Czechoslovakia. It was received by the new prime minister, Dr. Emil Hacha, since Eduard Benes (pronounced “Beh-nesh”) had resigned. According to this ultimatum, if in 24 hours the Czech administration, police and army had not evacuated the town of Teschen (in Czech, Cesky Tesin), the Polish army would invade the area.

The Czechs yielded immediately. That very day they abandoned Teschen, which was then annexed to Poland. The four signatory powers of the Munich Agreement—the UK, France, Germany and Italy—did not intervene. It is true that they had guaranteed the boundaries established in Munich, but such a guarantee cannot exceed the wishes of the guaranteed entity.

The Prague government did not even ask to be supported against the Poles, who presented their demands in brutal fashion, as a fait accompli, and giving a clearly insufficient time limit in their ultimatum. The Munich signatories understood that one cannot go against nature and that Czechoslovakia could only subsist in its new form as long as the Slovaks wanted it to.

Chamberlain and Daladier had been received enthusiastically on their return to London and Paris. Peace had been saved! Except for the influential minority of the members of the war clan, there was not a single English or French citizen who wanted to go to war to save a tyrant like Benes. A furious Churchill recounte d 2 that mobs applauded Chamberlain and Daladier on their returns from Munich.

(This was certainly a depressing display of democracy to such a dapper democrat as Churchill. He had spent his life praising the benefits of democracy, only to describe contemptuously as a “vociferous mob” people who did not want to follow him to war.)

Meanwhile other “democrats,” the Soviet Russians, had received the news of the Munich Agreement with holy indignation, and Chamberlain had been burned in effigy in Red Square in Moscow. Litvinov officially attended this democratic Soviet “voodoo” ceremony. As far as we know, the British Government did not file a diplomatic protest. 3 Can you imagine the outcry in the world media if, for example, Leon Blum had been burned in effigy in Berlin when the Franco-Soviet Pact was signed?

POLAND ATTACKS

The attack by Poland on Czechoslovakia was “carried out with the voraciousness of a hyena,” wrote the journalist Henri De Kérillls. The attack was the death blow for the Czechoslovak state. The return of the Sudetenland to Germany meant Prague had lost 40 percent of the industry and one-third (the most industrious) of the population. However, the loss of Teschen, more importantly than its strategic or economic interest, meant that Czechoslovakia did not inspire anyone with respect.

And so, even though in Paris the attitude of Poland caused great disgust and inspired diatribes against the rulers of Warsaw, suddenly there were new, even bigger concerns. Hungary noted that, contrary to its promises contained within the agreements signed in Munich, Czechoslovakia did not grant internal administrative autonomy to its Magyar minority.

Consequently Hungary turned to the governments of the Four Great Powers urging them to compel Prague to carry out its promises.

MAYHEM IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA

The Czechoslovak state definitively collapsed on October 6, when Slovakia proclaimed its autonomy within the Czechoslovak state. Prague recognized the Slovak autonomous government, led by Father Tiso. On October 10 in Uzhorod, an autonomous Carpatho-Ukraine (Subcarpathian Ruthenia) government was formed, chaired by Andrej Brody, who was also instantly recognized by Prague. A week later, however, Brody was arrested by the Czech police. Dr. Hacha, who had replaced Benes as head of state, sent a Czech general, Leo Prchala to Bratislava, naming him a member of the Slovak government. The measure was unconstitutional. On March 10 Prague struck another blow against the autonomous regimes that its constitution guaranteed and the government of Carpatho-Ukraine was removed en bloc .

A day later Father Tiso, president of the autonomous government of Slovakia, was arrested along with two of his ministers. The Slovaks poured onto the streets in Bratislava in protest, and there were many dead and wounded on both sides.

Under pressure from the populace, Prague released Tiso, ordering him to form a government. He refused because Czech soldiers were occupying Slovakia and Leo Prchala was still a mandatory member of the Slovak government. Meanwhile, three Czechoslovak state central governments formed by Dr. Hacha fell within a month.

Despite representing an important segment of the population, Karmassin, leader of the German minority in Bohemia (in Prague alone there were about 200,000 Germans) was not invited to hold any position in the three governments, despite being entitled to it according to the Czechoslovak constitution.

THE FINAL COLLAPSE

Hitler interpreted all these measures by Prague as a violation of the Munich Agreement, in which he had recognized the new Czech borders upon the express condition that the Czechs would “solve the issue of national minorities by peaceful means, constitutionally and without oppression.” So when, on March 14, 1939, Hungarian troops entered the regions of Ungvar and Munkacs, Berlin recognized the annexation. Two days later, the Hungarians occupied the Carpatho-Ukrainian region, immediately establishing an autonomous government presided over by Brody, who had been released from prison.

On March 17, Slovakia proclaimed its full independence. The Czechoslovak state had crumbled. It no longer existed. Poland too had re-mobilized and massed its troops on the Czech border. Slovakia and Ruthenia (Carpathian Ukraine) placed themselves under the protection of the Reich, i.e., they retained their full sovereignty but signed agreements with Berlin that placed them, in exchange for Germany’s political and military protection, within the orbit of Germanic influence.

There followed, inevitably, border frictions between the Czechs on the one hand, and Slovaks and Poles on the other. In view of the aggravation of the situation, Dr. Hacha and his minister of Foreign Affairs Chavlkovski asked to be received by Hitler. The Fuehrer berated them for their constant breaches of the Munich Agreement in regard to national minorities and announced that early the next morning German troops would enter Bohemia and Moravia. Dr. Hacha fainted on hearing these words and had to be treated by the Fuehrer’s own doctor. Upon regaining consciousness, his first action was to communicate the news to Prague and stipulate that no resistance should be offered. Dr. Hacha then signed a document in which he “put the fate of the nation and the Czech people in the hands of the Fuehrer of Germany.” Hitler promised to “admit the Czech people under the protection of the Reich and guarantee it an independent development suited to its national traits.” 4

Today, historians have no doubt that the document signed by Dr. Hacha was not drafted by him. Dr. Hacha went to Berlin to get a kind of protection—and in politics protection means dependence—similar to that obtained by the Slovaks and Ruthenians. But he found himself presented with the fait accompli of a “protectorate,” similar to that in which Morocco found itself at that time in relation to France and Spain.

Hitler was irritated, with good reason, with the Czech government, and wanted to make it pay for its depredations against ethnic Germans formerly under its protection. This was a political mistake. Attributable to Hitler? Attributable to von Ribbentrop? I believe, frankly, that it was both, but especially, in this instance, Hitler. I find it hard to believe that Hitler himself did not draft the document signed by Hacha. For us it is very clear that Dr. Hacha was a liberal, and a liberal does not talk about “destiny” in this historical circumstance. A liberal does not refer to the nation and the people, differentiating between them. Finally, a head of state who is going to ask for protection does not faint when the “protector” announces that his troops will cross the border to ensure order.

Historian Andre-Francois Poncet, who cannot be described as a Germanophile, said:

The Slovaks and Ruthenians had obtained the autonomy that the Czechoslovak state constitution itself permitted them. But the Czechs refused to consider them as autonomous entities. For Hitler to wipe Czechoslovakia off the map it was sufficient for him to take sides with the Slovaks and Ruthenians, and when both were under the legal protection of Berlin, the Czechs found themselves legally absolutely alone. It is therefore evident that the Munich Agreement was violated first by Prague, and not by Berlin. 5

But, on the other hand, the Munich Agreement stated that the Four Powers undertook to consult each other to resolve issues of common interest. Hitler should, then, before admitting Slovaks and Ruthenians under his protection, have consulted with England and France. When he perceived that the Czechoslovak attitude, openly violating the Munich Agreement, was directed from London by Benes (who had exiled himself there voluntarily) and the English war clan, and from Moscow by Clement Gottwald 6 , he should have contacted the English and French prime ministers. And when the Slovaks and Ruthenians placed themselves under his protection, he should have notified them that they must place themselves under the protection of London and Paris as well.

Similarly, when Poland took control of Teschen vis military means, Berlin should have prevented it. Of course London and Paris should have done the same, and yet they remained unperturbed. What would have happened if Berlin had scrupulously observed the Munich Agreement? It would have been very difficult for the English and French governments to let the situation continue to escalate, ignoring complaints by Tiso, Volozin, the Hungarians and Hitler, without losing the respect of the world. Hitler did not need to hurry, since the bulk of the Germans in the Sudetenland had been rescued from Czech control and were not in danger. But he wanted to solve the problem in his own way and the Czechoslovak state exploded. We agree with A.J.P. Taylor himsel f 7 that the so-called “pounce on Prague” was a political mistake.

Even though, as noted by the Fuehrer, many Germans lived in Prague and had founded the first German university there, even though Bohemia and Moravia had formed parts of German states for centuries, the fact remained that those territories could no longer be considered German lands. Until the “pounce on Prague,” Hitler could present himself with all justice as a defender of the right of free yet dispossessed peoples. After the “pounce on Prague,” Hitler no longer held the moral high ground.

For instance, Dr. Hacha himself appeared in Berlin, of his own free will, only to be placed under the political orbit of the Reich, with the same conditions as the Slovaks and Ukrainians. Over time, and at peace, by simple socio-political osmosis, the Czech Republic (Bohemia-Moravia) would have merged with Germany. The rush, again, was a huge psychological and political mistake.

One cannot talk constantly about creating in the heart of Europe, itself, a protectorate, as if it were Berbers of the Maghreb or a black tribe from central Africa. It is understandable, however, that Hitler would be fed up with the politicians from “Chateau” Prague and not trust them. On a purely moral plane, one could even justify the famous “pounce on Prague.” But on a political plane, absolutely not, and for one simple reason: Hitler did not gain anything by it and instead lost strength in his position, hitherto impregnable, as champion of peoples’ right to self-determination.

It is possible, however, that the real reason Hitler moved to annex the Sudetenland, Bohemia and Moravia, turning them into protectorates, was a purely strategic evaluation of the situation. The “Czech aircraft carrier” 8 was a wedge of almost 1,000 square miles right in the midst of Germany. At the same time, given the democratic internal structure of the Czechoslovakian rump-state (Bohemia-Moravia) Hitler had no guarantee that Dr. Hacha would not soon be replaced by a follower of Benes and problems once again arise, resurrecting the threat of having a foreign nation largely contained within another nation’s borders.

Indeed, the USSR rightly felt threatened by Germany. The threat could materialize as a direct military attack, as a political-economic blockade and/or as assistance, directly or indirectly, to Ukrainian nationalists by Berlin. This was described in its large lines in Mein Kampf , and after settling the outstanding issues with the West, Germany could turn to the East. In Munich a tacit agreement had been reached: Europe for Europeans. The USSR would be left out of discussions about European issues. England and France would stay out of eastern Europe. Hungary and the new Slovakia would join the Reich in an anti-Communist political block, while Poland—whose relations with Germany were excellent and which had collaborated with the Reich in the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia—would accentuate its anti-Communist policy.

In the Central European block that was being erected against the USSR, led by Germany, Czechoslovakia was an obstacle. It was a pebble in the gears of the powerful war machine that was being forged. None of its neighbors regretted the disappearance of the artificial state, and Hitler—this time, yes—implemented the policy of fait accompli himself. All the generals approved. As for von Ribbentrop and von Neurath, the career diplomats, while not openly disapproving of Hitler’s Czechoslovakia policy, were not so sure. In any case, Czechoslovakia had disappeared, and the USSR felt itself more than ever in quarantine.

Chamberlain, in the House of Commons, responded coolly to a question of Labour leader Clement Attlee: “The state whose borders we attempted to guarantee has collapsed from within. Therefore, the government of his Majesty does not consider itself obligated, any longer, with respect to Prague.”

In other words, Hitler now had a free hand in the East: exactly what he had always wanted.

ENDNOTES:

1 The Munich Agreement was a settlement permitting Nazi Germany’s annexation of Czechoslovakia’s areas along the country’s borders mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans in the Sudetenland. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, and signed in 1938 by the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Italy without the presence of Czechoslovakia.

2 Winston S. Churchill: Memoirs .

3 Archibald Maule Ramsay: The Nameless War .

4 Arnold Toynbee: Hitler’s Europe .

5 The History of the Vanquished , Bochaca, Joaquin, Part I, p. 124.

6 Clement Gottwald, the Czechoslovakian Communist Party leader, later purged (physically liquidated) by Stalin for being a Troskyite and “cosmopolitan,” i.e., Zionist.

7 A.J.P. Taylor: The Origins of the Second World War .

8 This expression was coined by Pierre Cot, French minister of Air: “ Tchécoslovaquie, porte-avions de la Democratie ” (Czechoslovakia, aircraft carrier of Democracy). Clemenceau, Poincare and Briand had said several times that Czechoslovakia was intended, in event of war, to serve as a base for bombing Germany. And in Memorandum 1 of the Czech Delegation to Versailles is written, without euphemisms: “The special situation of Czechoslovakia makes it, necessarily, the mortal enemy of Germany.”

http://mail.americanfreepress.net/news/latest/index.php/campaigns/we266bxwc8413/forward-friend/ny110xaj463f6

Remember: 10% off retail price for TBR subscribers. Use coupon code TBRSub10 if you are an active subscriber to claim your discount on books and other great products, excluding subscriptions.

Order online from the TBR Store using the links above or call 202-547-5586 or toll free 877-773-9077 Mon.-Thu. 9-5 ET with questions or to order by phone.

Know someone who might be interested in our books?

Forward this email to your friend by clicking here.

|