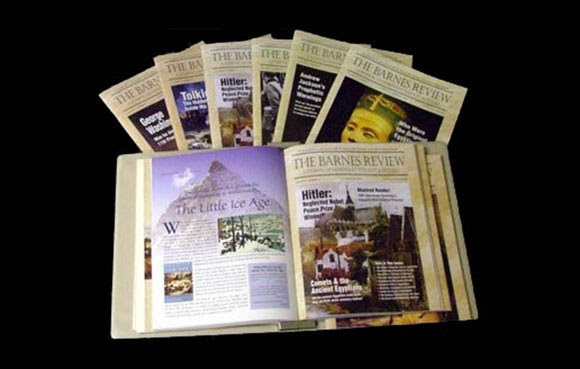

The article below is a sample of the best of The Barnes Review magazine. Please consider susbscribing to the magazine by clicking here.

TBR History Article - Hitler Sets FDR Straight About the Situation in the Sudetenland

INTRODUCTION BY PETER STRAHL

At the end of World War I, significant portions of historically German lands in Eastern Europe were cut up politically and handed over to avaricious Slavic nations and ethnic groups, more than once to the benefit of the spread of Communism.

In a previous issue of TBR (July/August 2011), we demonstrated the barbarity and betrayal this meant for Germans in a significant portion of Silesia, which was annexed illegally by Poland. The Sudeten Germans may have suffered even more. The countries of Bohemia and Moravia, which for centuries had been part of, first, the Holy Roman Empire and later the Austro-Hungarian empire, and which had been, by and large, culturally German for at least as long, were suddenly parceled up without regard for the people or their culture. The largest part of the region was, by a dictatorial fiat of the war victors, simply handed over to the ethnic minority of Czechs, much to the chagrin of the area’s Hungarians, Slovaks and Romanians. But it was the Sudeten Germans who were most hated by their new overlords. They suffered under a persecution so brutal as to threaten their existence.

In 1938, the situation had become extreme. The Sudeten Germans wished to be reunited with the rest of their countrymen, but the Czech government preferred their annihilation. Sudetenland Germans then turned to the Third Reich for help against the threatened genocide.

Of course, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt were barking about the supposed German juggernaut moving toward a “global empire.” FDR sent a telegram to the Fuehrer, demanding that Germany stay out of “Czechoslovakia.” On September 28, 1938, Adolf Hitler gave his response.

Hitler’s answer to President Roosevelt demonstrates conclusively that the Fuehrer was not, as typically portrayed, a maniacal madman, but was seeking, via the least confrontational path possible, to rescue his German brethren being oppressed in the Sudetenland. At the end of the Fuehrer’s letter, we append the historical commentary of Siegfried Egel, the editor of

Historische Tatsachen (#85) in which the following first appeared. . . .

Hitler’s Sept. 1938 Telegram to FDR

Translated by Peter Strahl

ORIGINALLY From Historische Tatsachen, No. 85

[TELEGRAM]

[To: Franklin D. Roosevelt]

[From: Adolf Hitler]

Your Excellency has, in your telegram, which reached me on September 26, directed an appeal to me in the name of the American people, in the interest of keeping the peace, not to break off negotiations over the dispute that has arisen in Europe, and to seek a peaceful, honest and constructive settlement of [the Sudetenland] question.

Be assured that I value indeed the noble intention upon which your comments are borne, and that I share in every respect your view about the incalculable consequences of a European war. Precisely on this account, however, I can and must reject any responsibility of the German people and their leaders if, perhaps, further developments, against all my previous efforts, should in fact lead to the outbreak of hostilities.

In order to reach a just judgment on the Sudeten German problem under consideration, it is essential to direct one’s view to the events in which, ultimately, the origin of this problem and its dangers have their cause.

The German people laid down their weapons in the year 1918, in the firm trust that the conclusion of peace with their opponents of that time would realize the principles and ideals that were solemnly announced for it by President [Woodrow] Wilson, and were just as solemnly accepted as binding by all the belligerent powers.

Never in history has the trust of a people been more humiliatingly cheated, than as happened at that time. The terms of peace forced upon the defeated nations in the accords in suburban Paris [Versailles] have fulfilled nothing of the promises given. They have created instead a regime that made the defeated nations into the pariahs of the world, deprived of all rights,[a situation] which had to be recognized as untenable by every insightful person, right from the beginning.

One of the points in which the character of the 1919 diktat most clearly revealed itself was the foundation of the Czechoslovakian state and the establishment of its borders, without regard for history or nationality. Sudetenland was also incorporated into it, although this region had always been German, and even though its inhabitants, after the destruction of the Habsburg monarchy, had unanimously declared their will for union with the German empire. Thus, the right of self-determination, which had been proclaimed by President Wilson as the most important foundation of the life of a people, was simply denied to the Sudeten Germans.

But that is not all. In the 1919 accords, certain and, according to the text, far-reaching obligations were laid upon the Czechoslovakian state with regard to [citizens of] German nationality. From the beginning, these obligations also have not been observed. The League of Nations, in the assignment given to it to ensure the fulfillment of these obligations, has failed completely. Since then, Sudetenland stands in most bitter battle for the preservation of its German culture.

It was a natural and unavoidable development that, after the restrengthening of the German Reich and after the reunion with Austria, the longing of the Sudeten Germans for the preservation of their culture and for a closer bond with Germany increased. In spite of the loyal attitude of the Sudeten German Party and its leaders, the contrasts with the Czechs became ever more intense. From day to day, it became clearer that the government in Prague was not genuinely willing to make allowances for the most elementary rights of the Sudeten Germans. On the contrary, they attempted, with ever more violent methods, to bring about the Czechification of Sudetenland. It was unavoidable that these efforts led to ever-greater and more serious tensions.

The German government, in the first place, intervened in no way in this development of things and maintained its peaceful reserve even when the Czechoslovakian government, in May of this year, moved to a mobilization of its army under the completely fabricated pretext of a German concentration of troops. The rejection of a military response at that time in Germany only served, however, to strengthen the intransigence of the government in Prague. That was shown clearly by the course of the negotiations of the Sudeten German Party with the government regarding a peaceful settlement. These many negotiations produced the final proof that the Czechoslovakian government was far distant from truly grappling with the Sudeten German problem from the ground up and supplying a just solution.

In the meantime, the situation in the Czechoslovakian state, as is generally known, has become completely unbearable in the last weeks. The political persecution and economic repression thrown upon the Sudeten Germans has resulted in unutterable misery.

To characterize these circumstances, it is sufficient to point out the following:

We count, at the moment, 214,000 Sudeten German refugees, who were forced to abandon house and hearth in their ancestral homeland—and could only save themselves by crossing the German border—because they saw [in Germany] the single, last hope to escape the revolting Czech regime of violence and the bloodiest of terror. Countless dead, thousands of wounded, tens of thousands of [Sudeten Germans] detained and imprisoned, villages laid waste: these are the accusing witnesses before the world public of the outbreak of hostilities, long since carried out by the Prague government. [Y]ou, in your telegram, rightly fear speaking of the German economic life systematically destroyed for 20 years by the Czech government in the Sudeten German territory, which already carries within itself all the symptoms of disorder and collapse, which you foresee as the consequence of a war breaking out.

Those are the facts that have forced me, in my Nuremberg address of September 12, [1938] to speak out before the entire world. The outlawing of 3.5 million Germans in Czechoslovakia must come to an end. These people, if they by themselves can obtain no rights, must receive rights and help from the German Reich.

But in order to make a last attempt to reach the goal in a peaceful way, I have made concrete proposals for a solution to the problem, in a memorandum given over to the British Prime Minister [Neville Chamberlain] on September 23, which has since been made known to the public.

After the Czechoslovakian government previously declared itself in agreement with the British and French governments that the Sudeten German area of settlement should be separated from the Czechoslovakian state and united with the German Reich, the proposals of the German memorandum have no other goal than to bring about a swift, certain and just fulfillment of that Czechoslovakian agreement.

I am of the conviction that you, Mr. President, when you picture in your mind the entire development of the Sudeten German problem from its beginnings to the present day, will recognize that the German government has lacked neither patience nor a strong desire for a peaceful agreement. It is not Germany’s fault that there is a Sudeten German problem at all, or that the present untenable circumstances have developed.

The terrible fate of the human beings affected by the problem no longer permits a further deferment of its solution. The possibility of reaching a just settlement by agreement is therefore exhausted by the proposals of the German memorandum.

The decision is up to Czechoslovakia. It is not in the hands of the German government. In the hands of the Czechoslovakian government alone does the solution henceforth lie. Czechoslovakia must decide whether it wants peace or war.

(End of telegram; signed)

—Adolf Hitler

ORIGINAL AFTERWORD FROM UDO WALENDY

Meanwhile, the ambassadors of Britain and France, once again, unambiguously had to instruct the Czech national president, Eduard Benes, to resign. Were war to break out because of his refusal, he alone would be responsible for it. Britain and France would not fight for him.

The conference in Munich on September 29, 1938, was, with the inclusion of Italy’s head of state, Benito Mussolini, solely about setting a completion date for the cession of Sudetenland to the Reich and setting up working groups for the establishment and location of exact borders. This has all already been agreed upon by England, France and the Czechoslovakian Republic.

Upon return from Munich, [French Prime Minister Edouard] Daladier and Chamberlain were greeted in their capitals with jubilant ovations. The French parliament, with the exception of the Communists, approved the agreement. The English House of Commons voted approval, as well, on October 4, by a count of 369 to 150 (primarily from the Labour Party). For Winston Churchill, however, “the European balance [was] disturbed.”

The president of the plenary assembly of the League of Nations—a Peruvian—declared after approval of the Munich Agreement by the League of Nations: “Chamberlain’s name will today be blessed in all the homes of the Earth, for it is the name of peace.”

http://mail.americanfreepress.net/news/latest/index.php/campaigns/cl512qrdxt60f/forward-friend/ny110xaj463f6

Remember: 10% off retail price for TBR subscribers. Use coupon code TBRSub10 if you are an active subscriber to claim your discount on books and other great products, excluding subscriptions.

Order online from the TBR Store using the links above or call 202-547-5586 or toll free 877-773-9077 Mon.-Thu. 9-5 ET with questions or to order by phone.

Know someone who might be interested in our books?

Forward this email to your friend by clicking here.

|