|

|

The Editor’s Corner: A Matter of Trust

The outrageous politics of recent years has been caused, in part, by Americans’ declining faith in elites and elite institutions

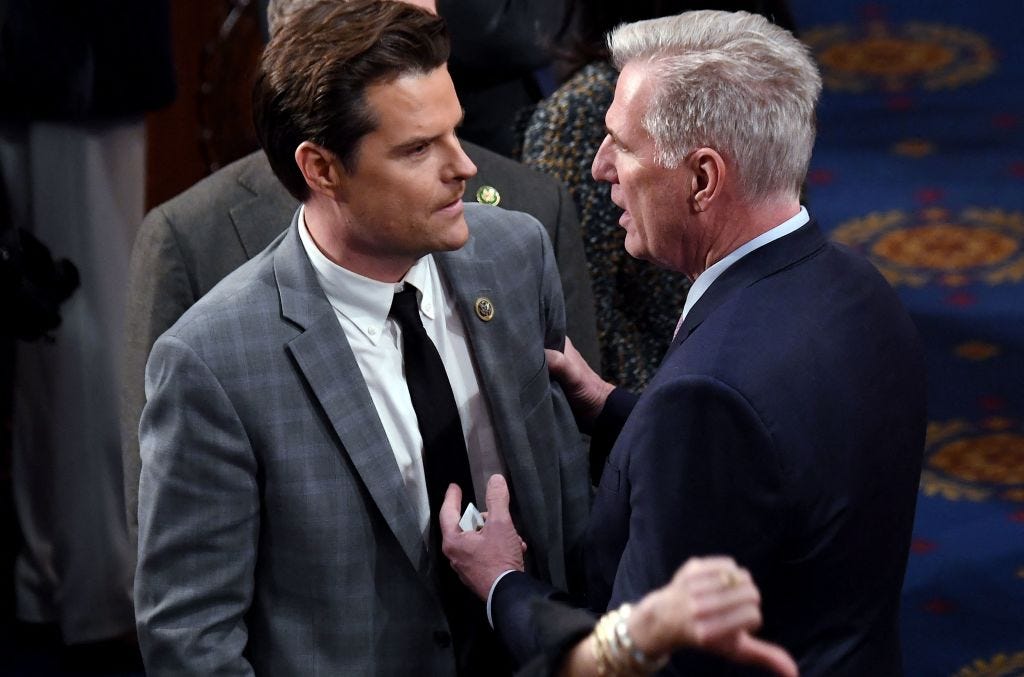

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s ouster last week has produced the usual hand-wringing about how dysfunctional our politics and our major political parties—particularly the Republican Party—have become. Specifically, the actions of Matt Gaetz and his small band of GOP arsonists have been held up as a particularly egregious example of how our system encourages and even rewards ridiculous posturing and nihilistic gestures over legislating and getting things done.

All this is completely true, of course. But I also think that some of the postmortems of last week’s happenings miss something deeper that has been driving us in this direction for some time—namely, the political fallout from the growing distrust of elites and elite institutions. A lot of thoughtful people of late, including some of our own contributors, have been writing about different aspects of this sense of alienation. It is happening across much of the political spectrum, but because so many of our institutions lean left, it is particularly prevalent among GOP voters.

Distrust of elites and elite institutions is at least as old as the American Republic. From Andrew Jackson to William Jennings Bryan to Donald Trump, America has periodically produced leaders who claim to act not just for common folk, but also against powerful elites. But lately, levels of distrust have reached unprecedented highs (at least in modern times), and that’s warping our politics in new ways.

Trust in what might be called our bedrock institutions is shockingly low. In a Gallup survey from last year, for instance, fewer than a third of Americans said they had “quite a lot” or “a great deal” of confidence in all but a few of the 16 large institutions they were asked about, including public schools (28%), the presidency (23%), big business (14%) and television news (11%). But Congress came in dead last at 7%. Is it any wonder, then, that voters are willing to send bomb throwers to Capitol Hill?

There are many possible answers to why this growing distrust has occurred, from the pernicious effects of social media to what the late historian Jacques Barzun, in “From Dawn to Decadence,” argued was our culture’s growing tendency to award notoriety to those who have achieved little or nothing. But in my view, any explanation needs to include the fact that, for the past 25 years, many elite institutions have performed very poorly. The list of failure is very long, running from our educational system to religious institutions. But there are some big standouts, such as the botched military campaigns in the war on terror, the near-collapse of our financial system in 2008 and failures of federal and state authorities during the COVID-19 pandemic. These and other developments have cast decision-makers and leading governing and social institutions in an extremely poor light. To put it another way, the trust deficit that I describe above has largely been earned.

This mistrust has been compounded by widespread perceptions that when mistakes, even colossal ones, are made, the people who make them not only do not take responsibility for their actions, but instead work to insulate themselves and those like them from the repercussions. For example, in an essay in Discourse last week, Jon Gabriel contends that while educated knowledge workers (including yours truly) largely rode out the pandemic lockdowns at home with their jobs and livelihoods intact, working-class people, small business owners and others farther from the decision-making class bore the brunt of the resulting job losses and the economic dislocation and damage. Likewise, the response to the 2008 financial crisis created the widespread perception that policymakers bailed out the culprits on Wall Street rather than their victims on Main Street. This belief, whether true or not, helped give birth to anti-elitist movements such as Occupy Wall Street and the Tea Party, and just a few years later, made voters much more open to nontraditional candidates such as Bernie Sanders and Trump.

Movements like Occupy, the Tea Party and others, such as Black Lives Matter, have had a number of things in common. First and foremost, they are driven by a great deal of anger and a demand for big change. But, as Martin Gurri and Arnold Kling discussed in Discourse three years ago, they also are often leaderless and have vague agendas.

Which brings us back to politics and political parties. Politicians from both parties have long sought to harness outside movements and use them to advance their own agendas. But anti-elitist movements are, by their nature, difficult to control. Many prominent Republicans and Democrats have ridden to victory on the coattails of these anti-elite movements, but in a sign of things to come, a number of high-ranking leaders—most famously Republican House Majority Leader Eric Cantor and House Democratic Caucus Chair Joe Crowley—also have been defeated by anti-elitist challengers from within their own parties. In addition, these movements generally aren’t interested in reforming or rebuilding institutions, but instead often advocate tearing them down (“defund the police”) or sharply curtailing their authority. They tend to be cauldrons that the party elders must constantly work to keep a lid on in order to stop them from boiling over.

While he was far from the first to try to channel this recent angry wave, Donald Trump’s genius was and is that he succeeded in molding much of this phenomenon into a huge movement based around himself. A man with decades of experience as a self-promoter and television personality, he was ideally suited to the role of avenging angel for the forgotten man. In a weird but brilliant bit of table-turning, he told his supporters that as a man born to wealth and a card-carrying member of the elite, he understood better than anyone how corrupt, arrogant, craven and incompetent his elite peers truly are. What’s more, he pledged to use this experience and knowledge to destroy these same elites.

Meanwhile, in spite of the best efforts of elites and their institutions, Trump has not gone away. In fact, it’s become a cliché to note that every time they go after him, he seems only to grow stronger, like a creature in a science fiction film that gets more powerful every time it’s hit with energy weapons.

This is the person who is the unequivocal figurehead of one of our two major parties. But of course, the GOP is really no longer really a political party—at least as it has been constituted up until now. It’s a royal court, surrounding a very capricious and touchy narcissist who has been crowned king. Below him, Tudor-like, sit a cadre of nervous courtiers, including members of what was the party establishment, who must find a way to get the business of government done while still pacifying their angry lord. This is not easy, which is one reason why now-former Speaker McCarthy went to the block last week for the crime of trying to keep the lights on. By leaning on Gaetz and his merry band to back off, Trump almost certainly could have saved McCarthy. He didn’t. That’s because his primary interest is not the Republican Party or its agenda, but himself and his agenda.

But it’s important to remember that Trump, for all his faults (and they are legion), is not ultimately the problem; he is merely a symptom of the problem. At some point in the not-too-distant future, when he leaves the political scene, things will not go back to “normal” as his many detractors hope. That’s because all the people who are angry and distrustful will still be angry and distrustful. What’s more, they have a point. Their problem is not that they misjudged the elites who have failed them and are continuing to fail them, even if not quite as badly as they may think. Their problem is that they have misjudged their champions, from two-bit clowns like Gaetz and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to big-league populists like Trump and Sanders.

So while the GOP may soon be able to begin life after Trump, it will not go back to being the party of Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell, much as this author might want it to. The GOP will need someone who can speak to this frustration with the status quo in a more productive and hopeful way without raging against everything, let alone condoning the sorts of stunts we saw last week. Maybe that’s too much to hope for. Maybe rank and file Republicans will embrace another outsider, another clown, who will strut across the stage and declare himself king. But maybe, just maybe, they will put their money on someone who promises to change the system from inside out, not with propane but with productive ideas and new policies. We’ll have to see.

In spite of the chaos now gripping the GOP, Democrats shouldn’t be too smug. So far, their party’s establishment has been better able than the Republicans to control the demons unleashed by our dissatisfactions, keeping a lid on Ocasio-Cortez and her co-religionists in The Squad as well as beating back two serious presidential bids from Sanders in 2016 and 2020. Again, part of the reason for their success is that most elite institutions lean left. But they’ve also held the demons at bay by embracing some of the more radical ideas espoused by these institutions, particularly our colleges and universities, on issues ranging from immigration and crime to gender and education—ideas that are not always very popular with voters.

Democrats may be able to squeak by in the next election by convincing enough people that Trump is worse than anything they’re offering, but even that is by no means certain. It’s also possible that this lurch to the left will catch up to them, much as it did in the 1970s and ’80s, when the GOP dominated presidential politics thanks in part to certain cultural ideas embraced by Democratic Party elites at the time. Furthermore, marching in lockstep carries its own risks, as we’ve seen in recent months: Members of the party establishment seem likely to stick with a presidential candidate they know is far too old to do the job because he is the incumbent and has a claim to another term.

Given the problems in both parties, there is much talk of a third party. But in an excellent piece in Discourse last week, political scientist Joe Romance urges caution. There are advantages to the two-party system, and besides, building a viable third party will take time and probably won’t have the impact in 2024 that some third-partiers may be hoping for.

As I argue in a Discourse essay that led off last week, our best course is to still work to reset and reform the institutions we already have, including our political parties. How we do that is a topic for another essay, or essays. But I believe that working to make institutions more responsive to the needs of average people will have a host of benefits, including helping to quell some of the worst aspects of our political life today.

Meanwhile…

What I’m Reading: Although the modern novel was invented in the 18th century, the art form did not really find its footing until the early 1800s. That being said, the 19th century turned out to be a great (possibly the greatest) age for novels. Authors such as Austen, Tolstoy, Hawthorne, Flaubert and Dickens, to name but a few, produced some of the richest and most enduring fiction of all time. But no list of great 19th-century novelists would be complete without George Eliot. From the 1850s until her death in 1880, Eliot (the pen name for Mary Ann Evans) was one of the most popular authors in the English-speaking world. Today, novels like “Silas Marner,” “Adam Bede” and “The Mill on the Floss” are still highly regarded and widely read. But her masterpiece, the greatest of her children, is “Middlemarch.”

I first read this great novel in college, getting completely lost in the world Eliot spends nearly 800 pages creating—the fictional town of Middlemarch and its varied inhabitants. I have come back to “Middlemarch” at least three times and am doing so again now. Like Tolstoy’s “War and Peace,” “Middlemarch” introduces the reader to a wide panorama of different characters, all set against a fascinating historical backdrop—England in the early 1830s, a time of great social, technological and political change. It was the beginning of the railroad age, but also a time of expanding religious and political rights.

Amid this backdrop, the novel focuses on four young men and women, each of whom is searching for greater meaning and purpose in life. With a setup like this, it won’t surprise you to learn that “Middlemarch” is very much a novel of ideas, asking big questions about the nature of progress, justice and happiness. But it is also a great psychological novel, with dozens of wonderful, memorable characters all interacting in a series of interweaving storylines. It is a 15-course feast of a book, and once you start it, as I discovered decades ago in college, you won’t want to put it down.

And while I’m at it: In 1994 the BBC produced a six-part adaptation of Middlemarch that does the novel justice. The series was penned by Andrew Davies (who would go on to write what I consider to be the best adaptation of Pride and Prejudice) and stars Rufus Sewell, Juliet Aubrey and Douglas Hodge as well as a number of wonderful British character actors, including Patrick Malahide and Robert Hardy.

Thank You

We’ve wrapped up our first week on Substack, and I’m happy to report that the launch has exceeded our expectations. We’ve welcomed many new readers this week, and we look forward to welcoming even more in the days and weeks ahead. I want to thank you, gentle reader, for helping us make this transition a success. And I want to offer special thanks to our new subscribers—I hope you’ll continue to enjoy the work of our great stable of writers.

Take care and see you next week.

New This Week

Robert Tracinski, “Where Is the D.C. Uniparty When We Need It?”

Daniel M. Rothschild, “Reducing Political Polarization by Respecting Human Dignity”

Jon Gabriel, “Won’t Get Fooled Again”

Joe Romance, “Is Now the Time for a Third Party?”

David Masci, “We Have Everything We Need”

Ben Klutsey, “Escaping the Identity Trap” (with Yascha Mounk)

Satya Marar and Rishab Sardana, “Putting Amazon in a Box”

David Masci, “Introducing the Editor’s Corner”

From the Archives

Tyler Cowen, “The Problem with the New Right's Skepticism of Elites”

Seth Moskowitz, “No Labels, No Chance”

Jennifer Tiedemann, “For the GOP, the Culture War Is Especially Risky”

You’re currently a free subscriber to Discourse .