Email

Food & Power - Justice Department Challenges Information-Sharing Scheme Between Meat Processors

| From | Claire Kelloway <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Food & Power - Justice Department Challenges Information-Sharing Scheme Between Meat Processors |

| Date | October 5, 2023 5:00 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Did someone forward you this newsletter?

Get your own copy by subscribing here [[link removed]], and to share this story click here. [[link removed]]

Is Food & Power landing in your spam? Try adding [email protected] to your contacts.

Photo courtesy of iStock.

Justice Department Challenges Information-Sharing Scheme Between Meat Processors.

Antitrust enforcers at the Department of Justice (DOJ) sued a data company [[link removed]], Agri Stats, for allegedly helping pork, chicken, and turkey processors raise prices. Agri Stats collects and shares detailed data on meat companies’ prices, wages, production levels, and profit margins. Processors allegedly used information obtained on Agri Stats to coordinate price increases, wage suppression, and production cuts since at least 2008. According to the DOJ’s complaint, one Smithfield executive described Agri Stat’s advice as: “Just raise your price.”

During the alleged conspiracy, turkey processing margins increased 300% in just three years, Tyson Foods alone saw its operating margin grow from 1.6% in 2009 to nearly 12% by 2016 [[link removed]], and wholesale pork prices rose over 50% in five years [[link removed]] after nearly a decade of relative price stability.

Meat buyers, workers, and farmers have brought several private antitrust suits against meatpackers that name Agri Stats as a co-conspirator, but the DOJ’s case singles out the company for exchanging “competitively sensitive information” to help restrain trade, in violation of the Sherman Act.

Agri Stats recruited virtually every major pork and poultry processor into its program by implementing a “give-to-get” policy, which required companies to hand over their data in exchange for their competitors’ data. Agri Stats installed software directly into their members’ computer systems to download internal reports, which Agri Stats then audited for accuracy. This provided a level of detail and timeliness far beyond what companies could glean through traditional industry research datasets – Agri Stats could share “nearly every quantifiable metric, sometimes in a matter of days,” according to DOJ’s complaint.

According to the DOJ’s complaint, Agri Stats didn’t just share information with competitors, it also advised them on how to maximize profits and discouraged processors from cutting prices or taking sales from one another. The company stated that its “paradigm” was to “increase [the] profitability of all participants.” Two employees from Smithfield and Tyson testified to antitrust enforcers that they could not think of a single time when their companies used Agri Stats reports to reduce consumer prices.

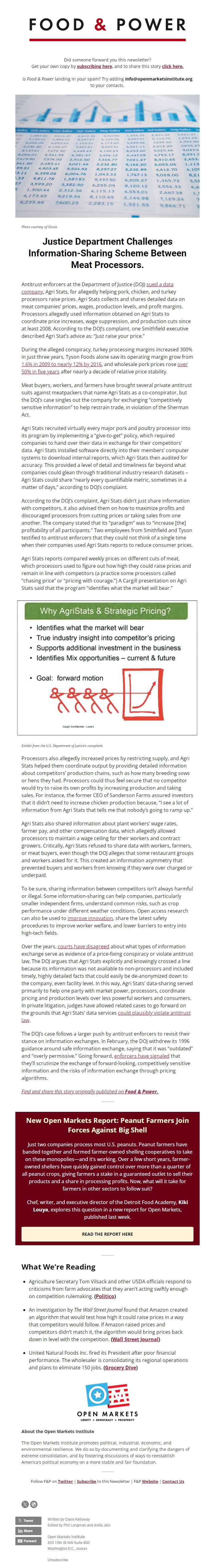

Agri Stats reports compared weekly prices on different cuts of meat, which processors used to figure out how high they could raise prices and remain in line with competitors (a practice some processors called “chasing price” or “pricing with courage.”) A Cargill presentation on Agri Stats said that the program “identifies what the market will bear.”

Exhibit from the U.S. Department of Justice's complaint.

Processors also allegedly increased prices by restricting supply, and Agri Stats helped them coordinate output by providing detailed information about competitors’ production chains, such as how many breeding sows or hens they had. Processors could thus feel secure that no competitor would try to raise its own profits by increasing production and taking sales. For instance, the former CEO of Sanderson Farms assured investors that it didn’t need to increase chicken production because, “I see a lot of information from Agri Stats that tells me that nobody’s going to ramp up.”

Agri Stats also shared information about plant workers’ wage rates, farmer pay, and other compensation data, which allegedly allowed processors to maintain a wage ceiling for their workers and contract growers. Critically, Agri Stats refused to share data with workers, farmers, or meat buyers, even though the DOJ alleges that some restaurant groups and workers asked for it. This created an information asymmetry that prevented buyers and workers from knowing if they were over charged or underpaid.

To be sure, sharing information between competitors isn’t always harmful or illegal. Some information-sharing can help companies, particularly smaller independent firms, understand common risks, such as crop performance under different weather conditions. Open access research can also be used to improve innovation [[link removed]], share the latest safety procedures to improve worker welfare, and lower barriers to entry into high-tech fields.

Over the years, courts have disagreed [[link removed]] about what types of information exchange serve as evidence of a price-fixing conspiracy or violate antitrust law. The DOJ argues that Agri Stats explicitly and knowingly crossed a line because its information was not available to non-processors and included timely, highly detailed facts that could easily be de-anonymized down to the company, even facility level. In this way, Agri Stats’ data-sharing served primarily to help one party with market power, processors, coordinate pricing and production levels over less powerful workers and consumers. In private litigation, judges have allowed related cases to go forward on the grounds that Agri Stats’ data services could plausibly violate antitrust law [[link removed]].

The DOJ’s case follows a larger push by antitrust enforcers to revisit their stance on information exchanges. In February, the DOJ withdrew its 1996 guidance around safe information exchange, saying that it was “outdated” and “overly permissive.” Going forward, enforcers have signaled [[link removed]] that they’ll scrutinize the exchange of forward-looking, competitively sensitive information and the risks of information exchange through pricing algorithms.

Find and share this story originally published on [[link removed]] Food & Power [[link removed]] . [[link removed]]

New Open Markets Report: Peanut Farmers Join Forces Against Big Shell

Just two companies process most U.S. peanuts. Peanut farmers have banded together and formed farmer-owned shelling cooperatives to take on these monopolies—and it’s working. Over a few short years, farmer-owned shellers have quickly gained control over more than a quarter of all peanut crops, giving farmers a stake in a guaranteed outlet to sell their products and a share in processing profits. Now, what will it take for farmers in other sectors to follow suit?

Chef, writer, and executive director of the Detroit Food Academy, Kiki Louya, explores this question in a new report for Open Markets, published last week.

READ THE REPORT HERE [[link removed]]

What We're Reading

Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack and other USDA officials respond to criticisms from farm advocates that they aren’t acting swiftly enough on competition rulemaking. ( Politico [[link removed]])

An investigation by The Wall Street Journal found that Amazon created an algorithm that would test how high it could raise prices in a way that competitors would follow. If Amazon raised prices and competitors didn’t match it, the algorithm would bring prices back down in level with the competition. ( Wall Street Journal [[link removed]])

United Natural Foods Inc. fired its President after poor financial performance. The wholesaler is consolidating its regional operations and plans to eliminate 150 jobs. ( Grocery Dive [[link removed]])

About the Open Markets Institute

The Open Markets Institute promotes political, industrial, economic, and environmental resilience. We do so by documenting and clarifying the dangers of extreme consolidation, and by fostering discussions of ways to reestablish America’s political economy on a more stable and fair foundation.

Follow F&P on Twitter [[link removed]] | Subscribe [[link removed]] to this Newsletter | F&P Website [[link removed]] | Contact Us [[link removed]]

Tweet [link removed] Share [[link removed]] Forward [link removed]

Written by Claire Kelloway

Edited by Phil Longman and Anita Jain

Open Markets Institute

655 15th St NW Suite 800

Washington D.C., xxxxxx

Unsubscribe [link removed]

Get your own copy by subscribing here [[link removed]], and to share this story click here. [[link removed]]

Is Food & Power landing in your spam? Try adding [email protected] to your contacts.

Photo courtesy of iStock.

Justice Department Challenges Information-Sharing Scheme Between Meat Processors.

Antitrust enforcers at the Department of Justice (DOJ) sued a data company [[link removed]], Agri Stats, for allegedly helping pork, chicken, and turkey processors raise prices. Agri Stats collects and shares detailed data on meat companies’ prices, wages, production levels, and profit margins. Processors allegedly used information obtained on Agri Stats to coordinate price increases, wage suppression, and production cuts since at least 2008. According to the DOJ’s complaint, one Smithfield executive described Agri Stat’s advice as: “Just raise your price.”

During the alleged conspiracy, turkey processing margins increased 300% in just three years, Tyson Foods alone saw its operating margin grow from 1.6% in 2009 to nearly 12% by 2016 [[link removed]], and wholesale pork prices rose over 50% in five years [[link removed]] after nearly a decade of relative price stability.

Meat buyers, workers, and farmers have brought several private antitrust suits against meatpackers that name Agri Stats as a co-conspirator, but the DOJ’s case singles out the company for exchanging “competitively sensitive information” to help restrain trade, in violation of the Sherman Act.

Agri Stats recruited virtually every major pork and poultry processor into its program by implementing a “give-to-get” policy, which required companies to hand over their data in exchange for their competitors’ data. Agri Stats installed software directly into their members’ computer systems to download internal reports, which Agri Stats then audited for accuracy. This provided a level of detail and timeliness far beyond what companies could glean through traditional industry research datasets – Agri Stats could share “nearly every quantifiable metric, sometimes in a matter of days,” according to DOJ’s complaint.

According to the DOJ’s complaint, Agri Stats didn’t just share information with competitors, it also advised them on how to maximize profits and discouraged processors from cutting prices or taking sales from one another. The company stated that its “paradigm” was to “increase [the] profitability of all participants.” Two employees from Smithfield and Tyson testified to antitrust enforcers that they could not think of a single time when their companies used Agri Stats reports to reduce consumer prices.

Agri Stats reports compared weekly prices on different cuts of meat, which processors used to figure out how high they could raise prices and remain in line with competitors (a practice some processors called “chasing price” or “pricing with courage.”) A Cargill presentation on Agri Stats said that the program “identifies what the market will bear.”

Exhibit from the U.S. Department of Justice's complaint.

Processors also allegedly increased prices by restricting supply, and Agri Stats helped them coordinate output by providing detailed information about competitors’ production chains, such as how many breeding sows or hens they had. Processors could thus feel secure that no competitor would try to raise its own profits by increasing production and taking sales. For instance, the former CEO of Sanderson Farms assured investors that it didn’t need to increase chicken production because, “I see a lot of information from Agri Stats that tells me that nobody’s going to ramp up.”

Agri Stats also shared information about plant workers’ wage rates, farmer pay, and other compensation data, which allegedly allowed processors to maintain a wage ceiling for their workers and contract growers. Critically, Agri Stats refused to share data with workers, farmers, or meat buyers, even though the DOJ alleges that some restaurant groups and workers asked for it. This created an information asymmetry that prevented buyers and workers from knowing if they were over charged or underpaid.

To be sure, sharing information between competitors isn’t always harmful or illegal. Some information-sharing can help companies, particularly smaller independent firms, understand common risks, such as crop performance under different weather conditions. Open access research can also be used to improve innovation [[link removed]], share the latest safety procedures to improve worker welfare, and lower barriers to entry into high-tech fields.

Over the years, courts have disagreed [[link removed]] about what types of information exchange serve as evidence of a price-fixing conspiracy or violate antitrust law. The DOJ argues that Agri Stats explicitly and knowingly crossed a line because its information was not available to non-processors and included timely, highly detailed facts that could easily be de-anonymized down to the company, even facility level. In this way, Agri Stats’ data-sharing served primarily to help one party with market power, processors, coordinate pricing and production levels over less powerful workers and consumers. In private litigation, judges have allowed related cases to go forward on the grounds that Agri Stats’ data services could plausibly violate antitrust law [[link removed]].

The DOJ’s case follows a larger push by antitrust enforcers to revisit their stance on information exchanges. In February, the DOJ withdrew its 1996 guidance around safe information exchange, saying that it was “outdated” and “overly permissive.” Going forward, enforcers have signaled [[link removed]] that they’ll scrutinize the exchange of forward-looking, competitively sensitive information and the risks of information exchange through pricing algorithms.

Find and share this story originally published on [[link removed]] Food & Power [[link removed]] . [[link removed]]

New Open Markets Report: Peanut Farmers Join Forces Against Big Shell

Just two companies process most U.S. peanuts. Peanut farmers have banded together and formed farmer-owned shelling cooperatives to take on these monopolies—and it’s working. Over a few short years, farmer-owned shellers have quickly gained control over more than a quarter of all peanut crops, giving farmers a stake in a guaranteed outlet to sell their products and a share in processing profits. Now, what will it take for farmers in other sectors to follow suit?

Chef, writer, and executive director of the Detroit Food Academy, Kiki Louya, explores this question in a new report for Open Markets, published last week.

READ THE REPORT HERE [[link removed]]

What We're Reading

Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack and other USDA officials respond to criticisms from farm advocates that they aren’t acting swiftly enough on competition rulemaking. ( Politico [[link removed]])

An investigation by The Wall Street Journal found that Amazon created an algorithm that would test how high it could raise prices in a way that competitors would follow. If Amazon raised prices and competitors didn’t match it, the algorithm would bring prices back down in level with the competition. ( Wall Street Journal [[link removed]])

United Natural Foods Inc. fired its President after poor financial performance. The wholesaler is consolidating its regional operations and plans to eliminate 150 jobs. ( Grocery Dive [[link removed]])

About the Open Markets Institute

The Open Markets Institute promotes political, industrial, economic, and environmental resilience. We do so by documenting and clarifying the dangers of extreme consolidation, and by fostering discussions of ways to reestablish America’s political economy on a more stable and fair foundation.

Follow F&P on Twitter [[link removed]] | Subscribe [[link removed]] to this Newsletter | F&P Website [[link removed]] | Contact Us [[link removed]]

Tweet [link removed] Share [[link removed]] Forward [link removed]

Written by Claire Kelloway

Edited by Phil Longman and Anita Jain

Open Markets Institute

655 15th St NW Suite 800

Washington D.C., xxxxxx

Unsubscribe [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Open Markets Institute

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor