| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Why cities should see Housing First as a tool for decarceration |

| Date | September 11, 2023 4:39 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Unconditional housing can reduce chronic homelessness, reduce incarceration, and improve quality of life.

Prison Policy Initiative updates for September 11, 2023 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Seeking shelter from mass incarceration: Fighting criminalization with Housing First [[link removed]] Providing unconditional housing with embedded services can reduce chronic homelessness, reduce incarceration, and improve quality of life – especially for people experiencing substance use disorder and mental illness. [[link removed]]

by Brian Nam-Sonenstein

Housing is one of our best tools for ending mass incarceration. It does more than put a roof over people's heads; housing gives people the space and stability necessary to receive care, escape crises, and improve their quality of life. For this reason, giving people housing can help interrupt a major pathway to prison created by the criminalization of mental illness, substance use disorder, and homelessness.

For this briefing, we examined over 50 studies and reports, covering decades of research on housing, health, and incarceration, to pull together the best evidence that ending housing insecurity is foundational to reducing jail and prison populations. Building on our work detailing how jails are (mis)used to manage medical and economic problems [[link removed]] and homelessness among formerly incarcerated people [[link removed]], we show that taking care of this most basic need can have significant positive downstream effects for public health and safety.

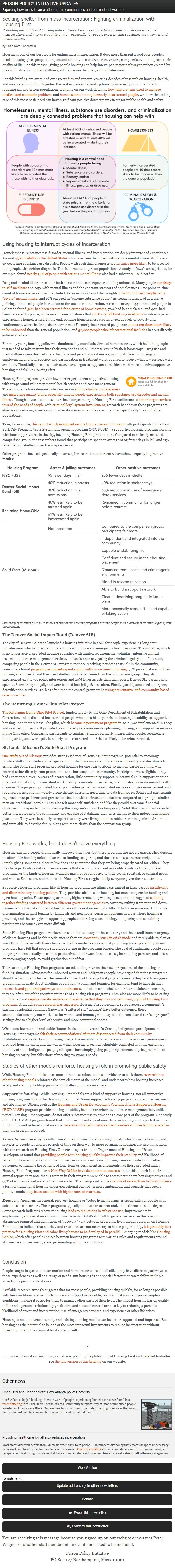

Using housing to interrupt cycles of incarceration

Homelessness, substance use disorder, mental illness, and incarceration are deeply intertwined experiences. Around 45% of adults in the United States [[link removed]] who have been diagnosed with serious mental illness also have a co-occurring substance use disorder. People with such dual diagnoses are 12 times more likely [[link removed]] to be arrested than people with neither diagnosis. This is borne out in prison populations. A study of Iowa's state prisons, for example, found nearly 54% of people with serious mental illness [[link removed]] also had a substance use disorder.

Drug and alcohol disorders can be both a cause and a consequence of being unhoused. Many people use drugs to self-medicate [[link removed]] and cope with mental illness and the constant stressors of homelessness. One point-in-time count of homelessness across the United States in 2022 found that roughly 21% of unhoused people had a "severe" mental illness [[link removed]], and 16% engaged in "chronic substance abuse." As frequent targets of aggressive policing, unhoused people face constant threats of criminalization. A recent survey of 441 unhoused people in Colorado found 36% had been arrested for a crime of homelessness, [[link removed]] 70% had been ticketed, and 90% had been harassed by police, while recent research shows that 1 in 8 city jail bookings in Atlanta [[link removed]] involved a person experiencing homelessness. In the end, policing homelessness creates a vicious cycle of poverty and confinement, where basic needs are never met: Formerly incarcerated people are almost ten times more likely to be unhoused [[link removed].] than the general population, and 52,000 people who left correctional facilities [[link removed]] in 2017 directly entered shelters.

For many years, housing policy was dominated by moralistic views of homelessness, which held that people just needed to take matters into their own hands and pull themselves up by their bootstraps. Drug use and mental illness were deemed character flaws and personal weaknesses, incompatible with housing or employment, and total sobriety and participation in treatment were required to receive what few services were available. Thankfully, decades of advocacy have begun to supplant these ideas with more effective supportive housing models like Housing First.

Housing First programs provide low-barrier permanent supportive housing with wraparound voluntary mental health services and case management. These programs have demonstrated success in ending chronic homelessness [[link removed]] and improving quality of life [[link removed]], especially among people experiencing both [[link removed]] substance use disorder and mental illness [[link removed]]. Though advocates and scholars have for years urged Housing First facilitators to better target services [[link removed]] toward the needs of people [[link removed]] with criminal legal system involvement [[link removed]], research has shown these programs are effective in reducing arrests and incarceration even when they aren't tailored specifically to criminalized populations.

Take, for example, this report which examined results from a 10-year follow-up [[link removed]] with participants in the New York City Frequent Users System Engagement program (NYC FUSE) - a supportive housing program working with housing providers in the city, including Housing First practitioners. Compared to a closely matched comparison group, the researchers found that participants spent an average of 95 fewer days in jail, and 256 fewer days in shelters, over the 10-year period.

Other programs focused specifically on arrest, incarceration, and reentry have shown equally impressive results:

Summary of findings from four studies of supportive housing programs serving people with a history of criminal legal system involvement.

The Denver Social Impact Bond (Denver SIB)

The city of Denver, Colorado launched a housing initiative in 2016 for people experiencing long-term homelessness who had frequent interactions with police and emergency health services. The initiative, which is no longer active, provided housing subsidies with limited requirements, voluntary intensive clinical treatment and case management services, and assistance navigating the criminal legal system. In a study comparing people in the Denver SIB program to those receiving "services as usual" in the community, researchers found program participants spent significantly more time in housing [[link removed]]: 77% percent stayed in their housing after 3 years, and they used shelters 40% fewer times than the comparison group. They also experienced 34% fewer police interactions and 40% fewer arrests than their peers. Denver SIB participants spent 27% fewer days in jail, and were booked into jail 30% less often. Finally, participants used emergency detoxification services 65% less often than the control group while using preventative and community-based care more often [[link removed]].

The Returning Home-Ohio Pilot Project

The Returning Home-Ohio Pilot Project [[link removed]], funded largely by the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, linked disabled incarcerated people who had a history or risk of housing instability to supportive housing upon their release. The pilot, which became a permanent program [[link removed]] in 2012, was implemented in 2007 and reached 13 prisons. It provided coordinated prerelease reentry planning, housing, and supportive services in five Ohio cities. Comparing participants to similarly situated formerly incarcerated people, researchers found participants were 40% less likely to be rearrested and 61% less likely to be reincarcerated.

St. Louis, Missouri's Solid Start Program

One study out of Missouri [[link removed] Start- supportive housing, social support, and reentry transitions.pdf] provides strong evidence of Housing First programs' potential to encourage positive shifts in attitude and self-perception, which are important for successful reentry and desistance from crime. The Solid Start program provided housing for one year to about 30 men on parole at a time, who entered either directly from prison or after a short stay in the community. Participants were eligible if they had experienced over 10 years of incarceration, little community support, substantial child support or other financial obligations, no consistent work history, a maxed-out sentence, or a mild-to-moderate mental health disorder. The program provided housing subsidies as well as coordinated services and case management, and required participation in weekly group therapy sessions. According to data from 2010, Solid Start participants reported fewer problems and greater satisfaction with their accommodations compared to a group of similar men on "traditional parole." They also felt more self-sufficient, and like they could overcome financial obstacles to independent living, viewing the program's support as temporary. Solid Start participants also felt better integrated into the community and capable of stabilizing their lives thanks to their independent home placement. They were less likely to report that they were living in undesirable or criminogenic environments and were able to describe future plans with more clarity than the comparison group.

Housing First works, but it doesn't solve everything

Housing can help people dramatically improve their lives, but these programs are not a panacea. They depend on affordable housing units and access to funding to operate, and those resources are extremely limited. Simply giving someone a place to live does not guarantee that they are being properly cared for, either. They may have particular safety and service needs that are not guaranteed or readily available through these programs, or the kinds of housing available may not be conducive to their social, spiritual, or cultural needs and values. Even successful models like Housing First struggle to help everyone given these constraints.

Supportive housing programs, like all housing programs, are filling gaps caused in large part by insufficient and discriminatory housing policies [[link removed]]. They provide subsidies for housing, but must compete for funding and open housing units. Fewer open apartments, higher rents, long waiting lists, and the struggle of cobbling together funding scattered between different government agencies [[link removed]] to cover everything from rent and down payments to physical and mental health care all make it exceedingly difficult to house someone. Add to this discrimination against tenants by landlords and neighbors, persistent policing in areas where housing is provided, and the struggle of supporting people amid rising costs of living, and placing and sustaining participants becomes even more difficult.

Some Housing First program workers have noted that many of these factors, and the overall intense urgency of clients' housing and health needs, means they are constantly stuck in crisis mode [[link removed]] and rarely able to plan or work through issues with their clients. While the model is successful at producing housing stability, many providers have felt that people should be staying in the programs longer. The goal of graduating people out of the program can actually be counterproductive to their work in some cases, introducing pressure and stress, or encouraging people to avoid graduation out of fear.

There are steps Housing First programs can take to improve on their own, regardless of the housing or funding situation. Advocates for unhoused women and indigenous people have argued that these programs should be far more inclusive. The general approach of Housing First programs means they tend to engage a predominantly male street-dwelling population. Women and femmes, for example, tend to have distinct traumatic and gendered pathways to homelessness [[link removed]], and often avoid shelters for fear of violence - meaning they are often out of the recruitment range of Housing First programs. They also are more likely to be caring for children and require specific services and assistance that they may not get through typical Housing First programs [[link removed]]. Although some [[link removed](HF] research [[link removed] of Housing First Configuration and Crime and Social Connectedness Among Persons With Chronic Homelessness Histories.pdf] has suggested [[link removed]] Housing First placements spread across a community's existing residential buildings (known as "scattered site" housing) have better outcomes, these accommodations may not work best for women and femmes, who may benefit from shared (or "congregate") settings due to a higher level of security and more communal spaces.

What constitutes a safe and stable "home" is also not universal. In Canada, indigenous participants in Housing First programs felt their accommodations left them disconnected from their community [[link removed] Complex Implementation Contexts- Overcoming Barriers and Achieving Outcomes in a National Initiative to Scale Out Housing First in Canada.pdf]. Prohibitions and restrictions on having guests, the inability to participate in smudge or sweat ceremonies in provided housing units, and the way in which housing placement eligibility conflicted with the customary mobility of some indigenous people, all expose how simply giving people apartments may be preferable to housing precarity, but falls short of meeting everyone's needs.

Studies of other models reinforce housing's role in promoting public safety

While Housing First models have some of the most robust bodies of evidence to back them, research into other housing models [[link removed]] reinforces the core elements of the model, and underscores how housing increases safety and stability, holding promise for challenging mass incarceration.

Supportive housing: While Housing First models are a kind of supportive housing, not all supportive housing programs follow the Housing First model. Some supportive housing programs do require treatment and abstinence. Others, such as the Housing and Urban Development Veterans Affairs Supported Housing (HUD-VASH) [[link removed](HUD%2DVASH)] program provide housing subsidies, health care referrals, and case management but, unlike typical Housing First programs, do not offer substance use treatment as a core part of the program. One study of the HUD-VASH program found that while participants spent more time in housing and reported increased functioning and reduced substance use, veterans who had substance use disorders still needed more services [[link removed]] than the program provided.

Transitional housing: Results from studies of transitional housing models, which provide housing and services to people for shorter periods of time on their way to more permanent housing, are also in harmony with the research on Housing First. One 2010 report from the Department of Housing and Urban Development found that providing people with housing quickly improves their stability [[link removed]] and likelihood of remaining housed. It also found that longer periods in transitional housing were associated with better outcomes, confirming the benefits of long-term or permanent arrangements like those provided under Housing First. Programs like A New Way Of Life have demonstrated success [[link removed]] under this model: In their 2022 annual report, they note that 41 women in their program were able to access permanent housing that year and 99% of women served were not reincarcerated. That being said, some analysis of research on [[link removed]] halfway houses [[link removed]] - a form of transitional housing under correctional control - is more ambiguous, and suggests that such a punitive model may be associated with higher rates of rearrests [[link removed]].

Recovery housing: In general, recovery housing or "sober living housing" is specifically for people with substance use disorders. These programs typically mandate treatment and/or abstinence to some degree. Some research indicates recovery housing leads to reductions in substance use [[link removed]], improvements in employment, and desistance from criminal activity. But it's difficult to generalize because the level of abstinence required and definitions of "recovery" vary between programs. Even though research on Housing First tends to indicate that sobriety and treatment are not necessary to house people stably, it is probably best practice for Housing First and sober living houses to be developed in parallel [[link removed](2016).]. Emerging models like Housing Choice [[link removed]], which offer people choices between housing programs with various rules and requirements around abstinence and treatment, are experimenting with this conclusion.

Conclusion

People caught in cycles of incarceration and homelessness are not all alike; they have different pathways to those experiences as well as a range of needs. But housing is one special factor that can stabilize multiple aspects of a person's life at once.

Available research strongly suggests that for most people, providing housing quickly, for as long as possible, with few conditions and as much choice and support as possible, is a practical way to improve people's conditions, making it easier for them to manage other parts of their lives. The impact housing has on quality of life and a person's relationships, attitudes, and sense of control are also key to reducing a person's likelihood of arrest and incarceration, use of emergency services, and experience of other life crises.

Housing is not a universal remedy and existing housing models can be better supported and improved. But housing has the potential to be one of the most impactful investments to reduce incarceration without investing more in the criminal legal system itself.

* * *

For more information, including a sidebar explaining the philosophy of Housing First and detailed footnotes, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Unhoused and under arrest: How Atlanta polices poverty [[link removed]]

1 in 8 Atlanta city jail bookings in 2022 were of people experiencing homelessness, we found in a recent briefing [[link removed]] with Luci Harrell of the Atlanta Community Support Project. 78% of unhoused people arrested in Atlanta were Black. Our analysis finds that the city is underinvesting in services that would help unhoused people, allowing far too many to end up behind bars.

Providing healthcare for all also reduces incarceration [[link removed]]

Most states disenroll people from Medicaid when they go to prison — an unnecessary policy that creates heaps of unnecessary paperwork and health risks for people recently released. Our 2022 briefing [[link removed]] explains how states can fix this problem now, and recaps research showing that states that have expanded Medicaid have seen lower arrest rates in all offense categories.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for September 11, 2023 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Seeking shelter from mass incarceration: Fighting criminalization with Housing First [[link removed]] Providing unconditional housing with embedded services can reduce chronic homelessness, reduce incarceration, and improve quality of life – especially for people experiencing substance use disorder and mental illness. [[link removed]]

by Brian Nam-Sonenstein

Housing is one of our best tools for ending mass incarceration. It does more than put a roof over people's heads; housing gives people the space and stability necessary to receive care, escape crises, and improve their quality of life. For this reason, giving people housing can help interrupt a major pathway to prison created by the criminalization of mental illness, substance use disorder, and homelessness.

For this briefing, we examined over 50 studies and reports, covering decades of research on housing, health, and incarceration, to pull together the best evidence that ending housing insecurity is foundational to reducing jail and prison populations. Building on our work detailing how jails are (mis)used to manage medical and economic problems [[link removed]] and homelessness among formerly incarcerated people [[link removed]], we show that taking care of this most basic need can have significant positive downstream effects for public health and safety.

Using housing to interrupt cycles of incarceration

Homelessness, substance use disorder, mental illness, and incarceration are deeply intertwined experiences. Around 45% of adults in the United States [[link removed]] who have been diagnosed with serious mental illness also have a co-occurring substance use disorder. People with such dual diagnoses are 12 times more likely [[link removed]] to be arrested than people with neither diagnosis. This is borne out in prison populations. A study of Iowa's state prisons, for example, found nearly 54% of people with serious mental illness [[link removed]] also had a substance use disorder.

Drug and alcohol disorders can be both a cause and a consequence of being unhoused. Many people use drugs to self-medicate [[link removed]] and cope with mental illness and the constant stressors of homelessness. One point-in-time count of homelessness across the United States in 2022 found that roughly 21% of unhoused people had a "severe" mental illness [[link removed]], and 16% engaged in "chronic substance abuse." As frequent targets of aggressive policing, unhoused people face constant threats of criminalization. A recent survey of 441 unhoused people in Colorado found 36% had been arrested for a crime of homelessness, [[link removed]] 70% had been ticketed, and 90% had been harassed by police, while recent research shows that 1 in 8 city jail bookings in Atlanta [[link removed]] involved a person experiencing homelessness. In the end, policing homelessness creates a vicious cycle of poverty and confinement, where basic needs are never met: Formerly incarcerated people are almost ten times more likely to be unhoused [[link removed].] than the general population, and 52,000 people who left correctional facilities [[link removed]] in 2017 directly entered shelters.

For many years, housing policy was dominated by moralistic views of homelessness, which held that people just needed to take matters into their own hands and pull themselves up by their bootstraps. Drug use and mental illness were deemed character flaws and personal weaknesses, incompatible with housing or employment, and total sobriety and participation in treatment were required to receive what few services were available. Thankfully, decades of advocacy have begun to supplant these ideas with more effective supportive housing models like Housing First.

Housing First programs provide low-barrier permanent supportive housing with wraparound voluntary mental health services and case management. These programs have demonstrated success in ending chronic homelessness [[link removed]] and improving quality of life [[link removed]], especially among people experiencing both [[link removed]] substance use disorder and mental illness [[link removed]]. Though advocates and scholars have for years urged Housing First facilitators to better target services [[link removed]] toward the needs of people [[link removed]] with criminal legal system involvement [[link removed]], research has shown these programs are effective in reducing arrests and incarceration even when they aren't tailored specifically to criminalized populations.

Take, for example, this report which examined results from a 10-year follow-up [[link removed]] with participants in the New York City Frequent Users System Engagement program (NYC FUSE) - a supportive housing program working with housing providers in the city, including Housing First practitioners. Compared to a closely matched comparison group, the researchers found that participants spent an average of 95 fewer days in jail, and 256 fewer days in shelters, over the 10-year period.

Other programs focused specifically on arrest, incarceration, and reentry have shown equally impressive results:

Summary of findings from four studies of supportive housing programs serving people with a history of criminal legal system involvement.

The Denver Social Impact Bond (Denver SIB)

The city of Denver, Colorado launched a housing initiative in 2016 for people experiencing long-term homelessness who had frequent interactions with police and emergency health services. The initiative, which is no longer active, provided housing subsidies with limited requirements, voluntary intensive clinical treatment and case management services, and assistance navigating the criminal legal system. In a study comparing people in the Denver SIB program to those receiving "services as usual" in the community, researchers found program participants spent significantly more time in housing [[link removed]]: 77% percent stayed in their housing after 3 years, and they used shelters 40% fewer times than the comparison group. They also experienced 34% fewer police interactions and 40% fewer arrests than their peers. Denver SIB participants spent 27% fewer days in jail, and were booked into jail 30% less often. Finally, participants used emergency detoxification services 65% less often than the control group while using preventative and community-based care more often [[link removed]].

The Returning Home-Ohio Pilot Project

The Returning Home-Ohio Pilot Project [[link removed]], funded largely by the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, linked disabled incarcerated people who had a history or risk of housing instability to supportive housing upon their release. The pilot, which became a permanent program [[link removed]] in 2012, was implemented in 2007 and reached 13 prisons. It provided coordinated prerelease reentry planning, housing, and supportive services in five Ohio cities. Comparing participants to similarly situated formerly incarcerated people, researchers found participants were 40% less likely to be rearrested and 61% less likely to be reincarcerated.

St. Louis, Missouri's Solid Start Program

One study out of Missouri [[link removed] Start- supportive housing, social support, and reentry transitions.pdf] provides strong evidence of Housing First programs' potential to encourage positive shifts in attitude and self-perception, which are important for successful reentry and desistance from crime. The Solid Start program provided housing for one year to about 30 men on parole at a time, who entered either directly from prison or after a short stay in the community. Participants were eligible if they had experienced over 10 years of incarceration, little community support, substantial child support or other financial obligations, no consistent work history, a maxed-out sentence, or a mild-to-moderate mental health disorder. The program provided housing subsidies as well as coordinated services and case management, and required participation in weekly group therapy sessions. According to data from 2010, Solid Start participants reported fewer problems and greater satisfaction with their accommodations compared to a group of similar men on "traditional parole." They also felt more self-sufficient, and like they could overcome financial obstacles to independent living, viewing the program's support as temporary. Solid Start participants also felt better integrated into the community and capable of stabilizing their lives thanks to their independent home placement. They were less likely to report that they were living in undesirable or criminogenic environments and were able to describe future plans with more clarity than the comparison group.

Housing First works, but it doesn't solve everything

Housing can help people dramatically improve their lives, but these programs are not a panacea. They depend on affordable housing units and access to funding to operate, and those resources are extremely limited. Simply giving someone a place to live does not guarantee that they are being properly cared for, either. They may have particular safety and service needs that are not guaranteed or readily available through these programs, or the kinds of housing available may not be conducive to their social, spiritual, or cultural needs and values. Even successful models like Housing First struggle to help everyone given these constraints.

Supportive housing programs, like all housing programs, are filling gaps caused in large part by insufficient and discriminatory housing policies [[link removed]]. They provide subsidies for housing, but must compete for funding and open housing units. Fewer open apartments, higher rents, long waiting lists, and the struggle of cobbling together funding scattered between different government agencies [[link removed]] to cover everything from rent and down payments to physical and mental health care all make it exceedingly difficult to house someone. Add to this discrimination against tenants by landlords and neighbors, persistent policing in areas where housing is provided, and the struggle of supporting people amid rising costs of living, and placing and sustaining participants becomes even more difficult.

Some Housing First program workers have noted that many of these factors, and the overall intense urgency of clients' housing and health needs, means they are constantly stuck in crisis mode [[link removed]] and rarely able to plan or work through issues with their clients. While the model is successful at producing housing stability, many providers have felt that people should be staying in the programs longer. The goal of graduating people out of the program can actually be counterproductive to their work in some cases, introducing pressure and stress, or encouraging people to avoid graduation out of fear.

There are steps Housing First programs can take to improve on their own, regardless of the housing or funding situation. Advocates for unhoused women and indigenous people have argued that these programs should be far more inclusive. The general approach of Housing First programs means they tend to engage a predominantly male street-dwelling population. Women and femmes, for example, tend to have distinct traumatic and gendered pathways to homelessness [[link removed]], and often avoid shelters for fear of violence - meaning they are often out of the recruitment range of Housing First programs. They also are more likely to be caring for children and require specific services and assistance that they may not get through typical Housing First programs [[link removed]]. Although some [[link removed](HF] research [[link removed] of Housing First Configuration and Crime and Social Connectedness Among Persons With Chronic Homelessness Histories.pdf] has suggested [[link removed]] Housing First placements spread across a community's existing residential buildings (known as "scattered site" housing) have better outcomes, these accommodations may not work best for women and femmes, who may benefit from shared (or "congregate") settings due to a higher level of security and more communal spaces.

What constitutes a safe and stable "home" is also not universal. In Canada, indigenous participants in Housing First programs felt their accommodations left them disconnected from their community [[link removed] Complex Implementation Contexts- Overcoming Barriers and Achieving Outcomes in a National Initiative to Scale Out Housing First in Canada.pdf]. Prohibitions and restrictions on having guests, the inability to participate in smudge or sweat ceremonies in provided housing units, and the way in which housing placement eligibility conflicted with the customary mobility of some indigenous people, all expose how simply giving people apartments may be preferable to housing precarity, but falls short of meeting everyone's needs.

Studies of other models reinforce housing's role in promoting public safety

While Housing First models have some of the most robust bodies of evidence to back them, research into other housing models [[link removed]] reinforces the core elements of the model, and underscores how housing increases safety and stability, holding promise for challenging mass incarceration.

Supportive housing: While Housing First models are a kind of supportive housing, not all supportive housing programs follow the Housing First model. Some supportive housing programs do require treatment and abstinence. Others, such as the Housing and Urban Development Veterans Affairs Supported Housing (HUD-VASH) [[link removed](HUD%2DVASH)] program provide housing subsidies, health care referrals, and case management but, unlike typical Housing First programs, do not offer substance use treatment as a core part of the program. One study of the HUD-VASH program found that while participants spent more time in housing and reported increased functioning and reduced substance use, veterans who had substance use disorders still needed more services [[link removed]] than the program provided.

Transitional housing: Results from studies of transitional housing models, which provide housing and services to people for shorter periods of time on their way to more permanent housing, are also in harmony with the research on Housing First. One 2010 report from the Department of Housing and Urban Development found that providing people with housing quickly improves their stability [[link removed]] and likelihood of remaining housed. It also found that longer periods in transitional housing were associated with better outcomes, confirming the benefits of long-term or permanent arrangements like those provided under Housing First. Programs like A New Way Of Life have demonstrated success [[link removed]] under this model: In their 2022 annual report, they note that 41 women in their program were able to access permanent housing that year and 99% of women served were not reincarcerated. That being said, some analysis of research on [[link removed]] halfway houses [[link removed]] - a form of transitional housing under correctional control - is more ambiguous, and suggests that such a punitive model may be associated with higher rates of rearrests [[link removed]].

Recovery housing: In general, recovery housing or "sober living housing" is specifically for people with substance use disorders. These programs typically mandate treatment and/or abstinence to some degree. Some research indicates recovery housing leads to reductions in substance use [[link removed]], improvements in employment, and desistance from criminal activity. But it's difficult to generalize because the level of abstinence required and definitions of "recovery" vary between programs. Even though research on Housing First tends to indicate that sobriety and treatment are not necessary to house people stably, it is probably best practice for Housing First and sober living houses to be developed in parallel [[link removed](2016).]. Emerging models like Housing Choice [[link removed]], which offer people choices between housing programs with various rules and requirements around abstinence and treatment, are experimenting with this conclusion.

Conclusion

People caught in cycles of incarceration and homelessness are not all alike; they have different pathways to those experiences as well as a range of needs. But housing is one special factor that can stabilize multiple aspects of a person's life at once.

Available research strongly suggests that for most people, providing housing quickly, for as long as possible, with few conditions and as much choice and support as possible, is a practical way to improve people's conditions, making it easier for them to manage other parts of their lives. The impact housing has on quality of life and a person's relationships, attitudes, and sense of control are also key to reducing a person's likelihood of arrest and incarceration, use of emergency services, and experience of other life crises.

Housing is not a universal remedy and existing housing models can be better supported and improved. But housing has the potential to be one of the most impactful investments to reduce incarceration without investing more in the criminal legal system itself.

* * *

For more information, including a sidebar explaining the philosophy of Housing First and detailed footnotes, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Unhoused and under arrest: How Atlanta polices poverty [[link removed]]

1 in 8 Atlanta city jail bookings in 2022 were of people experiencing homelessness, we found in a recent briefing [[link removed]] with Luci Harrell of the Atlanta Community Support Project. 78% of unhoused people arrested in Atlanta were Black. Our analysis finds that the city is underinvesting in services that would help unhoused people, allowing far too many to end up behind bars.

Providing healthcare for all also reduces incarceration [[link removed]]

Most states disenroll people from Medicaid when they go to prison — an unnecessary policy that creates heaps of unnecessary paperwork and health risks for people recently released. Our 2022 briefing [[link removed]] explains how states can fix this problem now, and recaps research showing that states that have expanded Medicaid have seen lower arrest rates in all offense categories.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor