|

How Saving One Hen Can Save Billions

The Sonoma Rescue Trial is a test of whether open rescue can go exponential.

What’s up this week

What if rescuing one hen has the power to save billions? That’s the question I ask in today’s newsletter. And the answer is that it can – but only if the rescue harnesses narrative, institutions, and movement mobilization. The Sonoma Rescue Trial, which is just weeks away, will be the next test of our ability to do these things.

Among the world’s most famous vegans, Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF), went to jail this week. SBF, who is accused of bilking his customers of billions of dollars at the FTX crypto exchange, had his bail revoked this week by Judge Lewis Kaplan, after the prosecution claimed that he engaged in witness tampering by sharing documents with the New York Times. I already have an unusual take on SBF’s case, but I have an even bigger problem with Judge Kaplan’s actions, which clearly violate the First Amendment. Remember, this is the same judge who falsely imprisoned Steven Donziger, the environmental attorney.

Researchers announced that they successfully transplanted pig kidneys into a human being – but failed to engage with the ethical implications. It’s bizarre to see the media recognize that animals like pigs are biologically close enough to human beings that we can use their organs, but not close enough to us to trigger any moral concerns,

Sonoma County is being called out for allowing a horse to be slowly mauled to death. Multiple witnesses describe an emaciated horse, dying in slow motion after being repeatedly attacked by a German Shepherd over many days, with no response from the authorities despite repeated calls. I can’t say I’m surprised.

Our next Open Rescue Advocates Meeting is coming up on Sunday, August 27, and it’ll be my last chance to hang out with you all – and take any of your questions - before trial. Here’s the link. Hope to see you in SF on the 27th.

Making the impossible, possible

One of the most common excuses I hear, among people who otherwise might get involved in the animal rights movement, is that the problem of animal abuse is simply too big.

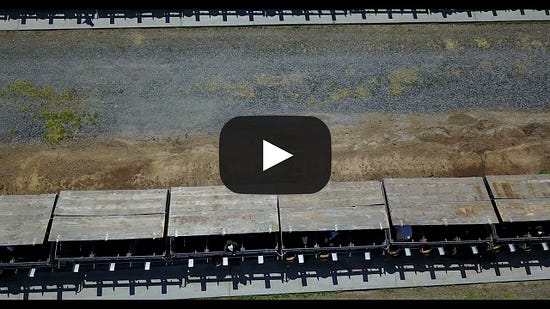

One can understand the feeling. Looking at even a single farm, such as this calf-raising operation in Northern California, can make the problem seem impossible.

When my friend Julianne Perry openly rescued a single calf from this place in 2017, it was an immense operation. How in heaven’s name could we possibly save all 12,000?

But this hopelessness confuses the nature of the problem. The fundamental obstacle we face is not the need for physical or financial resources to help all the animals in factory farms. Of course the movement can’t save all those billions directly.

The problem, rather, is one of “institutions” – the set of explicit and non-explicit rules by which human beings operate. Social scientists, such as the Nobel Prize winner Robert Fogel, have repeatedly found that these institutions are the key to creating change at scale. Fogel himself used the concept of institutional change to explain how antebellum slavery came to an end, despite its immense profitability leading right up to the Civil War: a powerful political movement shifted the norms of the nation. After this shift, all the resources that had been devoted to enslaving people were devoted to liberating them.

This is the power of institutions, and it is a more general phenomenon than any one case. The norms and institutions of human civilization are like its computer code, and they drive all the individuals operating under the code to pursue the program’s objectives, for better or worse. The best (and perhaps only) way to solve a deeply-ingrained problem in human civilization, in turn, is to rewrite this code.

But how do we do this?

Surprisingly, for animal rights, the answer starts with rescuing one animal. The reason is threefold. The first reason is that stories are crucial to garnering attention, and the rescue of a single animal — when done effectively — is among the most powerful stories in animal rights. The second reason is that open rescue has the power to embed the animal rights story into our institutions — despite enormous obstacles that usually prevent this sort of embedding from happening. And the third and most important reason is that open rescue has the power to mobilize a movement because it embraces both anger and hope — the two crucial emotions that have fueled movements through history.

All three of these factors will be at play in the Sonoma Rescue Trial. And my hope, above all others, is that our movement harnesses them to create change. Indeed, Im betting my life on it.

What’s in a story?

The philosopher Yuval Noah Hariri has written that our superpower, as a species, is our ability to engage in fiction. Stories are crucial for cooperation at scale. Take some examples: The founding history of a nation-state. The myths of a religion. Or even the dreams of a social movement. All of these stories bind people together towards common objectives — and, as living narratives, have the ability to evolve to face new challenges. (Consider how the American story has evolved over the last 200 years.) Indeed, it is only a mild overstatement to say that everything we accomplish as a species, we accomplish through stories.

But what makes a good story? The Harvard sociologist Marshall Ganz has identified some of the elements of storytelling that have been crucial to social movements:

A good story public story is drawn from the series of choice points that have structured the “plot” of your life – the challenges you faced, choices you made, and outcomes you experienced.

Challenge: Why did you feel it was a challenge? What was so challenging about it? Why was it your challenge?

Choice: Why did you make the choice you did? Where did you get the courage – or not? Where did you get the hope – or not? How did it feel?

Outcome: How did the outcome feel? Why did it feel that way? What did it teach you? What do you want to teach us? How do you want us to feel?

Of these factors, a compelling challenge is perhaps the most important. (The best-selling author Daniel Coyle once put it this way: the bigger the challenge, the better the story.)

But there is one other element missing from Ganz’s framework: an identifiable protagonist or victim. There is scientific research showing that empathy requires an identifiable individual. I explain this to people by asking them to imagine trying to have a deep and empathetic conversation with two other people at the same time. It’s extraordinarily difficult, as the human brain is engineered to appreciate the subjectivity of only one mind at a time. Indeed, this is why empathy with even one other person is hard; we are usually distracted by our own subjectivity and feelings! Asking humans to empathize with billions, in turn, is impossible. We simply don’t have the processing power to engage in empathy at scale.

What this means, for advocates, is that to engage the human mind and capacity for empathy, we need to tell the story of one, not of a billion. And this is precisely what open rescue does. The story of one individual in an open rescue harnesses what psychologists call the identifiable victim effect. And it has the natural structure of a great story: a unique character, an impossible challenge, and a life-changing choice. This is one of the main reasons that stores of rescue have had such a dramatic impact on the history of animal rights.

Making repression backfire

But it is not just that open rescue creates great stories. It also embeds these stories in our most crucial institutions. Think about the last few hundred years of American history, and the stories that matter most to our nation. They are, disproportionately, stories that have unfolded in court. Rosa Parks. Susan B. Anthony. Even relatively trivial stories like the trial of Johnny Depp. The courtroom is not just a platform for dramatic stories. It is the place where our most important stories are enshrined in law.

But it is usually impossible to get animals into court. The legendary attorney Steve Wise has spent a lifetime fighting for the law to recognize the personhood of animals and, despite great sympathy from the public, he has yet to have a winning case. Routinely, courts throw such lawsuits out immediately, on the grounds that animals simply have no standing to sue. Animals are invisible to the law.

This, again, is where open rescue comes in. By leveraging our own freedom, we can force the court to address the rights of animals. Indeed, recent conversations I’ve had with prominent constitutional law scholars have convinced me that criminal cases involving open rescue defendants are among the most promising avenues to push for institutional recognition of animal rights. Unlike most court cases involving animals, open rescue prosecutions involve a defensive (i.e., defending my rights) rather than offensive (i.e., taking away someone else’s rights) assertion of animal rights. For that reason, they are far more likely to succeed.

Building a movement

The third and most important reason for open rescue’s power, however, is that it is the perfect mix of anger and hope to mobilize a movement. The Stanford sociologist Doug McAdam was one of the first to identify these two emotions as the key ingredients for social change. And in a conversation I had with him a few years ago, he shared a stunning data point: even as Black people faced lynchings and repression in the 1960s, surveys showed them becoming more optimistic about the prospects for change.

McAdam coined a concept — cognitive liberation — to describe the shared grievance and shared hope that he saw in the Civil Rights Movement, and in numerous other movements in history. When movements effectively combined those two sentiments, huge masses of people felt irresistibly compelled to act. And those masses were an unstoppable force for change.

Open rescue, perhaps more than any other strategy in animal rights, combines these two emotions: anger and hope. It focuses our attention on the situation that angers us most: an animal abused, tortured, and left to die. But it does not drown us in despair; instead, it gives us hope for the future. “This poor creature, against all odds, was saved!” Open rescue is cognitive liberation come to life.

When I went around the country in April 2015, after our first open rescue in Sonoma County, I had a faint hint as to open rescue’s power to mobilize. But even I could not imagine what happened just a few years later. Hundreds of us walked right into a factory farm and began to take the sick and dying animals out. And I’m publishing for the first time, footage from the entrance to that facility when the police walked with us out of the factory farm.

Watching this clip brought tears to my eyes. This is the vision. This is the strategy. This is the path to change. And, precisely because of its power, the industry wants this to stop — to put people like me in prison for helping to bring this vision to life.

But, as I shared with attendees at the Open Rescue Experience this past weekend, what happened in May 2018 in Sonoma County is just the tip of the iceberg.

Because, as I wrote as the Smithfield trial approached, when I expected a guilty verdict and incarceration, it is just not just vegans and animal rights activists who can be mobilized by open rescue, by the power of anger and hope. It’s all of us.

No matter what happens to Paul and I at trial, so long as people keep seeking and speaking truth, Big Ag’s efforts will inevitably fail. I know this because, when the fur industry came after the movement, it merely fueled our efforts to create change — leading to the historic ban on fur in California in 2019. I know this because of the academic literature on the Backlash Effect, which shows that efforts to repress nonviolent movements will backfire, if the activists can maintain solidarity in the face of persecution. And I know this, most of all, because I know that, in our hearts, we are a compassionate species. Indeed, compassion — and the ability to feel what others feel — is arguably our greatest superpower. And when that superpower is unleashed, we will become who we were meant to be:

Caretakers of this earth, and its living beings.

I did not have enough faith in my convictions to believe that this message would be embraced by a rural, conservative jury in Utah. But it was, and the jury acquitted me. My world will never be the same.

Now, if all of us embrace this message, and fight to win not just in Sonoma County, but in the factory farms and slaughterhouses across the nation, we can end institutionalized animal exploitation in one generation.

It all starts with saving one life.

The Simple Heart is free today. But if you enjoyed this post, you can tell The Simple Heart that their writing is valuable by pledging a future subscription. You won't be charged unless they enable payments.