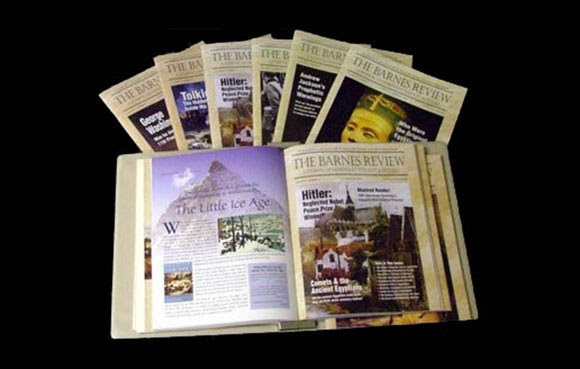

The article below is a sample of the best of The Barnes Review magazine. Please consider susbscribing to the magazine by clicking here.

The Normans: Blessing or Curse?

INTRODUCTION

It has been nearly 500 years now since anyone, with open military force, successfully conquered the English, a fierce and resolute white mixture of Germanics with a dash of Kelts and pre-Indo-Europeans. The Spanish armada, Napoleon Bonaparte and others all failed to defeat the “Sceptered Isle.” But back in 1066, a group of people, a mixture of French and Scandinavian origin, called Normans (from the French word for “Northmen”), slew the English nobility and its common soldiers at Hastings, just days after the English army had rushed south from defeating an invasion by Danish Vikings in northern England.

The Normans were descended from Norse people who had settled in Neustria (today called Normandy) in the 9th and 10th centuries and adopted the Gallo-Romance language of Old French, spoken there by the natives, while retaining a fair amount of Norse vocabulary. The new language is called “French Norman” by linguists. The Viking settlers of Normandy took up the native French way of life almost completely.

The French themselves were a mixture of Germanic Frankish invaders with an underlying Romanized population of Kelts, known as Gauls. After invading England, a new dialect evolved there, called “Anglo-Norman.”

Hastings was the catastrophic end of purely Anglo-Saxon England—of its original language, its Germanic culture and its semi-isolation from the troubles of the European mainland and of the world. Ever since that October day in 1066, Normans and the Jewish immigrants they brought in have played a large role in England’s leadership. Were they a blessing or a curse, or both?

By John de Nugent

A few years ago this writer wrote to a comrade in England and happened to mention that I had ancestors from both the English common people, the Anglo-Saxons, and also from the Normans who conquered England in 1066. His reply surprised me and made me realize that, while the two races have largely amalgamated, the English have not yet grown very fond of their former overlords:

“Normans, eh? I guess we can forgive you that.”

My first naive thought was that he had been overly influenced by the tales of Ivanhoe and how the legendary Robin Hood had led the common people in resistance to the cruel usurper on the throne of England, the Norman Prince John, while John’s brother, King Richard Lion Heart, was away on the crusades.

But then I read about the shocking “Harrowing of the North” (the north of England) by William the Conqueror right after the conquest, and discussed further below. The term referred to the utter devastation of man, woman, child, livestock and even plants in that very Yorkshire where my maternal grandfather, John Thomas Coldwell, was born. At least 100,000 Yorkshire men and women perished. Even the pope, Adrian IV, who at the time was, uniquely, an Englishman, and who actually had supported William’s claim to the throne of England, threatened in disgust and horror to excommunicate him.

And Hereward “the Exile” (perhaps better known as Hereward “the Wake”; c. 1035-1072), the Anglo-Saxon or Anglo-Danish champion (possibly the son of Lady Godiva and Earl Leofric) who fought the Normans for years from a fort in a swamp, may have been murdered by the enemy after he had honorably surrendered.

And I read that J.R. Tolkien, the great Oxford professor and author of The Lord of the Rings (the three-part movie version of these novels has been seen by 2 billion film goers) actually loathed the Normans as nightmarishly cruel, and as money-grubbing corruptors of souls. He decried their lust for the “ring of gold,” and their terrorizing of the decent, honest English common folk, symbolized in Lord of the Rings by the brave little hobbits in their rustic hobbit holes. I began to get an inkling of why that English comrade would write me as he had.

England before the Normans

One reason why Hereward had risen up against the Normans was the atrocious “Harrowing of the North” of England in 1069-70. Britain had once been a freedom-loving “hobbit” country, an island of Germanic and Keltic folk, and they certainly were not interested in being forced to learn French, a foreign tongue, or becoming any Frenchman’s serf.

Northern England was barely under the control of any king. In fact, there was only one castle in all of Anglo-Saxon England . . . because castles were meant to not just resist invaders but also to resist uprisings by hostile, enslaved local populations. England did not need castles for lording it over a free people who accepted their rulers.

The old English did respect their own people; they did not fear them (or need to), and when they called for volunteers, as King Alfred the Great did in 877 against the invading Vikings, folks came a-running to help. Nor did the Anglo-Saxon kings have a heavy tax system, because no one was building vastly expensive castles with moats, nor did the folk feel a need to pay for a standing, professional army, and in fact they dreaded such a thing as a threat to their freedom.

Militias are cheap, with part-time soldiers and weekend warriors, and professional armies on the other hand do cost a lot, but freedom isn’t free, as the expression goes, and the Anglo-Saxons lost it. For having only a militia they paid an incredible price—centuries of enslavement that, while less openly brutal than before, lasts, in this writer’s view, to this day.

Northern England, the region William the Conqueror would decide to devastate, had been settled heavily by both northern German Saxons and by the Scandinavian Germanic Danes, and was even richer in Nordic genes than the south. The dialect of Yorkshire, and the whole north, in fact, was heavily influenced by Danish, so much so that the Londoners from down south could barely understand it. Many nobles up there, in fact, were Danes. The region was even called “the Danelaw,” and the historians of today call that region, in that era, by the name “Anglo-Scandinavia.”

In fact, “English”-seeming place names that end in

-thorpe, -borough, -wick or -by, such as Oglethorpe, Warwick, Attleborough, Bixby, Hornby, Frisbee or Albee, all come, in reality, from the Danish. “By” is still today the Danish word for a village. Thus the meaning of the English word “by-laws” is “village laws,” hence one never hears of federal or state “by-laws,” but only the by-laws of towns, local clubs and associations. Hundreds of the most basic English words came in through the Danelaw, such as take, skin, sky, he, they, anger, bask, bawl, bet, build, blunder, crash, crazy and other basic “English” words.

(One can hear a northern English dialect—very hard for Americans to understand, because our own American accent comes from southeastern England—in the unique and touching 1997 English tragicomic film “The Full Monty,” written by a Simon Beaufoy—“Goodfaith” in French—with as Norman a name as you can imagine. It depicts six very desperate unemployed ex-steel mill workers in Sheffield who resort, quite bashfully, to putting on a nightclub striptease in their despair to raise money to pay their back bills and their child support. This is from the very area that William the Bastard, as the conqueror was also known, had genocided 900 years ago.)

Given both their heritages, Scandinavian and Saxon, the ingredients of a double bravery, the doughty Yorkshiremen up north told William the Bastard in no uncertain terms that he was not welcome as their new master after they saw how he was enslaving the south of England.

At the legendary Battle of Maldon, 75 years before, their brave Saxon brothers in southern England had already fought honorably to the very death rather than pay any tribute to Viking marauders. (They finally began paying Danegeld, “money for the Danes,” only after their total annihilation at Maldon). The Maldon Yorkshiremen of the year 1066 were just as brave as the men of Maldon had been a mere 75 years earlier.

In 1916 the great British poet Rudyard Kipling penned a notable, even jarring poem that expressed the innate Anglo-Saxon fierceness, resolve and hatred of oppression:

When the Saxon Begins to Hate

It was not part of their blood. / It came to them very late. / With long arrears to make good /When the Saxon began to hate. / They were not easily moved. / They were icy—willing to wait. / Till every count should be proved / Ere the Saxon began to hate. / Their voices were even and low; / Their eyes were level and straight. / There was neither sign nor show / When the Saxon began to hate. /It was not preached to the crows; / It was not taught by the state. / No man spoke it aloud / When the Saxon began to hate / It was not suddenly bred. / It will not swiftly abate. / Through the chilled years ahead / When time shall count from the date / That the Saxon began to hate.

Although this poem was composed during WWI, when Kipling had just lost his son at the front fighting the Germans, it reveals a fundamental mindset: “We don’t seek quarrels, we Saxons, but if you start it we will finish it.”

Old English becomes Norman English

The Old English language (also called Anglo-Saxon), which the English then spoke, was a dialect of northwestern German (with some Scandinavian thrown in, as stated above) because the Anglo-Saxons had come to Britain around A.D. 400 from Germany, right when Roman rule in Britain was collapsing. In fact, three whole provinces in Germany have the same ethnic word “Saxony” in them: Saxony, Lower Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt. (Dresden, bombed ironically to smithereens by the British in WWII, is in fact the capital of Saxony.)

But given the Germanic roots of English, as a boy in New England I always wondered why sheep meat, sheep flesh, was not called just that in English, like the related German Schafsfleisch (Schafs fleisch) . Why instead was sheep flesh called “mutton”? Why was the English word borrowed at all from the French-language “ mouton ”?

Why was swine flesh (as in the related German Schweinefleisch ) called “pork” (from the French “ porc ”), and why was calf flesh called, again after the French, “veal” ( veau )? Why was cow flesh called “beef” (from the French “ boeuf ”)? Why were the English names different for the animal out in the peasant’s field from the same animal when its meat was carved up on the lord’s table?

Why on Earth do court sessions in my native New England, such as in Massachusetts (one of the oldest British Colonies), still open with the bailiff calling out: “ Oyez, oyez, oyez ”? (“ Oyez ” is Anglo-Norman, meaning “Hear ye!”)

Why does the coat of arms of England say in French, “ Dieu et mon droit ” (“God and my right [shall me defend]”)? And why does the Order of the Garter motto proclaim in French: “ Honi soit qui mal y pense ” (literally, “Shamed be him who thinks evil of it”)?

Why do we have both the word “think” (German denk ) and the word “reflect” (French refléter )? Both “right” (German richtig ) and “correct” (French corriger )? Why was Henry VIII a “king,” but the usual adjective for anything having to do with a king is not “kingly” but instead “royal”? The king in France is called a roi .

Furthermore, why did Britain, an Anglo-Saxon/Keltic country, side in both world wars with Latin-oriented France and against a kindred nation, Germany, the very home of many of its honest, hardworking ancestors?

It all began with a brutal conquest in 1066 that eradicated Germanic rule in Britain and then an even more brutal genocide of those who rebelled against their enslavement.

William “the Bastard” (his original nickname, for he was born illegitimate, but after 1066 he was called “the conqueror”) had no respect for the Anglo-Saxons as brave and honorable foes. After massacring the English soldiers at the October 14, 1066 Battle of Hastings, 1 he resolved to also slaughter their helpless civilians to spread terror, and thence to annihilate the beautiful north English countryside to set a shock-and-awe, dread-provoking example: Submit or die.

Also fighting on the Norman side at the Battle of Hastings were unknown numbers of Bretons (who regarded Britain as their lost homeland), Flemings, Frenchmen, Poitevins, Angevins and Manceaux. Casualties were numerous on both sides, but the Englishry lost.

After the battle, William and his army marched about southern England, on Dover and on Canterbury, in a huge show of force, before he arrived on the outskirts of London. He met resistance in Southwark, and, in revenge, set fire to the area.

Londoners still refused to submit to William. He turned away and marched through Surrey, Hampshire and Berkshire, ravaging the once-beautiful green English countryside.

By the end of the year the people of London, surrounded by devastated lands, submitted to this man who can only be called a foreign terrorist. On Dec. 25, 1066, William was crowned king of England by Aldred, archbishop of York, at Westminster Abbey. But then the still-uncowed north of England rose up in revolt.

William begins his genocide

Orderic Vitalis (1075-1142) had a strong opinion of William’s reaction. He was an Anglo-Norman chaplain to Roger de Montgomery, a key friend and war companion of William (of the same family that later gave birth to Field Marshal Montgomery of WWII fame). He later became a monk in Normandy, and normally was an open admirer of Duke William for his skill and bravery as a soldier, ruler and builder of beautiful cathedrals.

However, Orderic wrote, in his chronicle Gesta Normannorum Ducum [“Deeds of the Norman Dukes”], of his horror at the Normans’ merciless scorched-earth policy toward the north.

It was far worse even than the “March to the Sea” through Georgia in 1864 by Union (federal) troops under Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman. (“Sherman,” by the way, is a classic Norman, not Saxon, name.)

From the Humber River to the Tees, for four seemingly unending years, 1066 to 1070, William’s rampaging cavalry burnt whole villages to the ground and killed the civilians of northern England.

The death toll is estimated at 150,000, with substantial social, cultural and economic damage to boot. Due to the scorched-earth policy, much of the land was laid waste and depopulated, a fact to which the famous Domesday Book , William’s great tax and inventory list of all the properties in England, readily attests in 1086, almost two decades later.

And it provoked as much bitterness toward the Normans as did, 800 years later, Gen. Sherman’s march through Georgia among Southerners, especially after the burning of Atlanta. (This wanton crime was memorably depicted in the 1939 film Gone with the Wind .)

Norman names abound

Besides “Sherman,” here are some other typical Norman names, and you will see them making a lot of history among the white, English-speaking peoples:

Allison, Angell, de la Beckwith, Curtis, Davison, Dawes, Duke, Nugent, Tiffany, Harris, Morris, Pierce (from Pierres, a name that no longer exists in France), Piper, Chase, Doggett, Fitzwater, Disney (d’Isigny), Drury, Dillon, Chamberlain, Grant, Gibbs, Goddard and Pinkerton, also Lindsay, Murdoch, Quincey, Day, Denny (as in the restaurant chain), Dench (actress Judy Dench), Dennis (as in nationalist author Lawrence Dennis) (from le Danois = the French word for “the Dane”), Denton (d’Eudon, a companion of the conqueror), Devine, Dillon (de Lion), Dingell (D’Angell); Agnew (Agneau), Cheney (de Chesne = “of the oak”), DeLay (former speaker of the House), Doocy (as in Steve Doocy, FOX news), Arby (as in the roast-beef chain, Darby, from d’Arby), Dunhill, as in the cigarettes (d’Oisnel); Fitzgerald, Fitzhugh, Pugh, Richmond, Landry (Dallas Cowboys coach), Blanchard, Montgomery, Cushing (Cuchon), Dorset, Dwight (de Doito), Dyer (d’Iore), Dyson (as in the chicken-processing giant in Arkansas from “Tesson”); Blanchett, Barrett, Beckett, Crockett (as in our Davey), East (as in the late U.S. senator and patriot from South Carolina, from d’Est), Edmonds, Everett, Fairfield (from Fierville; most names that end in “-field” come, not the Anglo-Saxon word “field,” but instead from the French “ille,” meaning “large town or city” in French); etc.

The horror of the Harrowing

The deliberate annihilation by William and his Normans of all food and livestock—like Stalin’s “holodomor” in the 1930s, a famine genocide the Soviet dictator deliberately caused in Ukraine—meant that anyone who survived the initial Norman massacres with the sword or lance would still die eventually of starvation over the northern European winter.

The land was even salted by the Normans—just as the Romans had done with Carthage—to destroy its fertility for decades forward.

As the monk Orderic Vitalis relates—and again, this Orderic was otherwise an admirer of William—the wretched survivors were reduced to the horrors of cannibalism. Some killed and ate their dying family members, and cracked open the skulls of the dead to devour their brains.

This is a dark chapter of British history, unequaled until the Irish genocide by Normans from 1550 to 1850, and then the bombing by Norman-ruled Britain of Dresden in 1945, which killed at least 350,000 civilians (and horrified many good English people).

This deliberate campaign of terror explains the pope’s threat of excommunication. Unsurprisingly, among the starved, wretched survivors—with their immune systems severely weakened by hunger, physical abuse (including rape) and emotional trauma—a plague followed, killing even more of England’s finest blood.

Orderic, though half Norman himself and a supporter, like the pope, of the winner, could find no way to defend William after this unparalleled holocaust:

The king stopped at nothing to hunt his enemies. He cut down many people and destroyed their homes and land. Nowhere else had he shown such cruelty. To his shame he made no effort to control his fury, and he punished the innocent with the guilty. He ordered that crops and herds, tools and food should be burned to ashes. More than 100,000 people perished of hunger. I have often praised William in this book, but I can say nothing good about this brutal slaughter. God will punish him.

Interestingly, after that prediction, in his later years William’s wife died prematurely, and his son Robert Curthose rose up in revolt against him, ravaging his father’s domains in France.

The older William then became grossly fat, and in 1087 he was told that King Philip of France had described him as resembling a pregnant woman. Feeling insulted, a furious William then mounted an attack on the French king’s territory. But after capturing and setting fire to the innocent city of Mantes, he was thrown high in the air by his horse, landed hard, groin first, on the metal pommel of his saddle, and died after three weeks of agony from a burst intestine.

Sadly, the four-year “Harrowing of the North” by William was just the beginning of a new, long, dark age of Norman oppression, of the crushing of ancient freedom for the English people, and soon after that for the Welsh, Scots and the Irish, against whom Norman “English” armies were sent.

In some ways the Norman Conquest was like the bolshevik Revolution, which only involved about 50,000 bolsheviks, who took over a vast country of 150 million. The Norman Conquest, like the bolshevik putsch, brought war, enslavement, exploitation and fear to the vast majority of the people.

And from this “harrowing” we can see that although the Normans had picked up the French language (from settling in northern France between 900 and 1066), and French certainly is the vehicle of a high culture full of wine, women, song, poetry, cuisine, beauty and elegance, the Normans themselves remained Viking marauders in their hearts, still being—to this very day—what the Anglo-Saxon “Battle of Maldon” poem fragment said once of the Vikings: “pirates,” “scavengers” and “slaughter-wolves.”

All the British peoples had to learn bitterly that “if you make it, a Norman will take it”—your land, your crops, your pride and, if possible, your wife’s or daughter’s virtue. It reminds one of what, over in Asia, the Mongol Genghis Khan once said boastfully, giving his own infamous, peculiar definition of pleasure:

“The greatest happiness is to scatter your enemy, to drive him before you, to see his cities reduced to ashes, to ride his horses, to see those who love him shrouded in tears, and to take to your chest his wives and daughters.”

Psychopaths in Power

In The Barnes Review of January/February 2007, this writer’s article “Psychopaths in History” discussed the large role played by psychopaths in world history.

I showed the latest scientific research on psychopaths, indicating that a shocking 4% or more of the general population may be psychopathic. I showed that we can now look back on 70 years of hard medical case studies of psychopaths by top doctors and scientists such as Hervey Cleckley of Oxford, Martha Stout of Harvard and Robert Hare of the University of British Columbia. And their medical findings have been buttressed since the 1990s by extensive physical brain scans of the cerebral tissue of certified psychopaths.

Many of these brain scans have been analyzed by Adrian Raine, Ph.D., an Oxford graduate who was a full professor at the University of Southern California from 1994-2007, and is now a professor of criminology and psychiatry at the Ivy League’s University of Pennsylvania.

These reports and brain scans all show that there are individuals who are born not just with a bad attitude—which of course sometimes can be changed by therapy, by sincere religious conversion, or just by making different friends.

So, with what we now know about psychopathy, can we go back in history and look at famous and infamous figures and determine—or speculate at least—whether or not they were psychopaths?

A TRAUMATIC YOUNG LIFE

The early life of William the Conqueror (circa 1028-1087) was full of extreme trauma, and such trauma can create a borderline psychopath, called in psychiatry a “disadvantaged psychopath.” William hardly led the safe and luxurious life of the current British royal children, such as the Prince William we see today.

Duke William (Guillaume) smarted from childhood over being mocked as “William the Bastard.” His mother was a beautiful French peasant girl, and his noble father, Robert, duke of Normandy, dubbed “Robert the Magnificent,” saw the fetching wench one day while riding by as she was washing clothes in a stream. In short order Robert the Magnificent got her with child, but never married her, of course, she being a peasant, though a beautiful one. But he did put the bastard son of this union defiantly on the ducal throne in 1035.

William was nearly murdered several times as a child by other nobles, and right in his own bedroom, as a young teen, he saw his manservant killed defending him from assassins with swords. He once had to flee in the pitch of night for his life on horseback, a very dangerous, high-speed ride—especially if one considers the rutty roads of that time, with of course no street lighting at all, low-hanging branches etc. William could have been thrown by a stumbling horse and broken his neck at any time.

Years of trauma may well have worsened William’s already bad psyche, and it was he who set the tone for Norman rule over England. Life for young William was a jungle of attempts on his life, and became a question of winning and living or losing and dying, crushing or being crushed—it was about masters and slaves.

I began in 2004 my own voyage into that part of my own ancestry, visiting Normandy, France (Rouen, Omaha Beach, and Caen, William’s capital) to learn about those Normans, the French-speaking Vi kings who had transformed England.

From ye olde “Angle-land,” Anglo-Saxon-land, which had been a mind-its-own-business island out in the North Sea, after 1066 it was turned into a land that was always on the attack: against Wales, then Ireland, then Scotland, then France, and eventually England attacked every major country on Earth, among them Holland, Germany, Italy, Spain, Denmark, Sweden, Turkey, Russia, the states of India, China etc, not to mention its own British Colonies in America after they sought to retain their original British freedom.

Pride goeth before a fall

In the end, exhausted and bankrupted by two world wars it could never afford against its mighty blood cousin, Germany, England’s power declined sharply in the 1950s. Its splendid isolation was over, and the “Sceptered Isle” of Shakespearean times became, after the latter half of WWII—just as French leader Charles de Gaulle had warned Winston Churchill (of the Norman Spencer family that also gave us Princess Diana)—“the [immovable] aircraft carrier of the United States.”

Admittedly, since the Norman Conquest of 1066, England also has been a land of military valor (Sir Francis Drake defeating the Spanish armada, Adm. Nelson stopping Napoleon, and the aerial Battle of Britain in 1940), but also of incredible culture, statecraft (the Magna Carta, Elizabeth I, Parliament), science (Sir Isaac Newton, and the Greenwich system of longitude and time), to make a very short list of a long list of honors.

But it also has been a country saddled with a government of unparalleled cruelty and treachery toward its very own people, toward white unity in general, and dedicated for centuries to annihilating the white Irish by war and famine, to crushing the white Scots, to aiding the Soviet bolsheviks in their hour of greatest peril when the fiends were at the point, twice, of losing to Germany (1918 and 1941), and fighting to subdue both their kindred in America and also their distant German relatives twice (1914-18 and 1939-45) in the original “Saxonland.”

The decline of the West was the result.

London—against every true interest of its subject peoples—has waged disastrous wars that have spoiled crucial moments of hope and unity in Western history. Its vile ruling class even destroyed, by going “politically correct” after WWII, its own vast and magnificent British empire by the process called decolonialization, which benefited neither the colonies nor Britain, and it let non-whites pour in to terrorize and displace the native British people.

The Norman ruling class gave away after 1945 what British lads and their valor had built up over the centuries, an empire which Hitler himself, who had fought the British in the trenches in WWI, highly admired and wished to save from the hostile designs of both U.S. leader Roosevelt and USSR ruler Stalin.

The flight of Rudolf Hess to Scotland in March 1941 was part and parcel of that unrequited Hitlerian dream of Anglo-German brotherhood. Already in 1940 Hitler had let 100,000 English soldiers escape from the beaches of Dunkirk, France—making a dramatic gesture of peace toward the British people and their government, while his Wehrmacht generals tore their hair out in frustration.

But London continued the war under the Norman Churchill (Spencer), showering bombs down on German civilian areas, until cousin Germany was pulverized . . . and the British empire, bankrupted by two world wars, was in hock to the bankers.

During the 1957 Suez Canal crisis, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower forced Britain to withdraw from Egypt, its last major colony, and the British lion meekly obeyed, the survival of the British pound at stake after Eisenhower threatened to trigger a currency crisis. Thus a psychopathic ruling class, the Normans, destroyed one of the mightiest nations of all time: its own Britain.

The Normans bring in the Jews

Above all, I can never forget or forgive this about the Normans: that it was they who brought the Jews into England for the first time. They shipped them in from Normandy to tax the English with grinding fees into despair and poverty, all to raise money for countless imperial Norman projects that involved sending England’s hardy Anglo-Saxon peasants overseas into foreign wars to die for their alien aristocrats.

And then, as we saw clearly in the 20th century with Rhodesia, London ordered those same doughty Englishmen to turn their flourishing, Brit-run colony over to stone-age blacks, and indeed turn it over to the very worst among them, to the murderous Robert Mugabe and his illiterate tribesmen. Why is English history, over and over, in effect so anti-English?

The Jews were expelled in 1290 by the Norman King “Longshanks” Edward I (but Longshanks did this only after decades of public uproar over both their usury and repeated allegations—many well-founded—of child ritual murder). However, some Jews stayed behind. Judaism was not being racially defined, and by the simple act of converting, by oath, to Christianity, and going to church a few times, one could stay.

Other Jews merely crossed the border into nearby Scotland, then still independent. When Scotland became part of a united Britain after 1603, the Scottish Jews were right back in.

By 1694, 400 years after the expulsion, the Jews were so firmly back in the saddle, having also come back from Holland as illegal immigrants in the 1680s, one by one, family by family, on ships, that they then could then found and control the “Bank of England.” As Lord Rothschild (Mayer Amschel Bauer Rothschild) infamously said: “Give me control of a nation’s currency and I care not who makes its laws.”

Interestingly, the Human Genome Project (HGP) has been shedding light on both Norman and Jewish genes as they moved into England. The HGP has been mapping all the genes of the human races as they spread out over the world (starting with the genes of scientist Craig Venter and Nobel Laureate James Watson of DNA fame). One can clearly see the Norwegian (also Norman) gene R1b1b2a1a1d moving from southern Norway down to Rouen, in Normandy, France, and then going up across the English Channel and into the eastern half of England.

One can also see a Jewish gene, the so-called Ashkenazi-Norman gene, labeled R1b1b2a1a4, on the move, a gene nicknamed Ivanhoe, evidently after Sir Walter Scott’s judeophilic novel.

This gene came from western Ukraine to the Baltic, through Germany, and stopped at Rouen, Normandy, France, before moving to the northern half of England and into Scotland.

As a result of these genes and their bearers, from 1066 on, English history changed, and not just in calling “swineflesh” by the French word “pork.” It became a land, as Shakespeare wrote, of a pound of flesh: rule by usurers.

The Normans did make England, a little island, into an incredibly powerful country that has changed the whole world. It is no surprise that these ruthless descendants of the Vikings transformed once-agricultural England into a supreme naval power. (The United States of America, the principal offshoot of Norman Britain, has continued this massive naval power.)

The Brits also have a will to win that the Normans gave them, and that has made them a valiant and conquering race.

May Britain overthrow its corrupt ruling class; may the infinite valor and genius of that island realm be put to use soon for the salvation of the West, and may a new blood brotherhood be reborn with their cousins in the original Saxon homeland, Germany. Those genes gave the fearless, steady, honest, innovative Anglo-Saxons so much that is superlative in their mighty race.

ENDNOTE:

1 The Normans showed no mercy, slaughtering the wounded where they lay. Those Englishmen unable to escape and hide in the woods were pursued and cut down by cavalry.

http://mail.americanfreepress.net/news/latest/index.php/campaigns/xz853m2967380/forward-friend/ny110xaj463f6

Remember: 10% off retail price for TBR subscribers. Use coupon code TBRSub10 if you are an active subscriber to claim your discount on books and other great products, excluding subscriptions.

Order online from the TBR Store using the links above or call 202-547-5586 or toll free 877-773-9077 Mon.-Thu. 9-5 ET with questions or to order by phone.

Know someone who might be interested in our books?

Forward this email to your friend by clicking here.

|