Email

SPECIAL REPORT | What WalletHub Got Wrong: A Closer Look at California's Energy Costs

| From | Center for Jobs & the Economy <[email protected]> |

| Subject | SPECIAL REPORT | What WalletHub Got Wrong: A Closer Look at California's Energy Costs |

| Date | August 7, 2023 4:00 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

No images? Click here [link removed]

The Center for Jobs and the Economy has released a special report that dissects WalletHub's assertion that California has affordable energy costs despite its high cost of living, but a detailed analysis exposes substantial flaws undermining the validity of this claim. For additional information and data about the California economy visit [[link removed].]

Flaws in the Numbers

In economic analysis, a basic rule learned early is: if your results don’t really reflect the real world you see, you probably made an error somewhere. In the case of the WalletHub piece, let us count the ways:

Reporting on a recent WalletHub [[link removed]] comparison, the Mercury News [[link removed]] ran a story with the astonishing claim that although California has one of the highest costs of living, “in terms of energy costs, it is surprisingly one of the most affordable in the country.” As a result of our policies, California has a high cost of living in large part because its energy costs are high, which help drive up the cost of everything else including high utility bills and high fuel costs that affect the costs of housing, goods, and services.

The Mercury News can only make its claim by accepting the WalletHub information without question, which upon even a cursory examination has substantial flaws. Putting aside the more detailed errors listed later, there are several problems with the WalletHub numbers:

1. Lack of a Common Denominator: The WalletHub study mixes different types of data without adjusting for a common comparison base, making it difficult to compare energy expenses across states accurately. The data attempts to compare household costs, like electricity bills, with individual costs, like gasoline prices, without converting them to a common unit of measurement, such as converting both to a per capita or per household basis. This is like mixing apples and oranges, and it can lead to misleading results. For example, a state with low household electricity costs but high individual gasoline prices might seem cheaper in energy expenses overall, but that might not be true when considering total energy expenditures for households. This skews the energy cost data and fails to give a meaningful comparison of energy expenses across different sources and states.

2. Generalized and Outdated Sources: The article only reports on generalized data sources without providing specific details, such as the calendar year, which is essential for context. Without this information, the data might be outdated and not accurately reflect the current energy cost ranking among states. For example, WalletHub has California as the 31st highest electricity bill, but in the latest data from US Energy Information Administration (12-month moving average), California has in fact vaulted into being the 13th highest. The same issue applies to gasoline costs. The most recent annual data from the US Department of Transportation on total vehicle miles traveled is from 2021 and presumably the source of the WalletHub calculations. Due to state-ordered closures during the pandemic, vehicle miles traveled was substantially lower in 2021 but especially in California – the last state to emerge from the pandemic-era closures – where restrictions caused less travel and lower gasoline usage compared to other states.

3. Variation in Different Energy Sources Ignored: The data also fails to consider that different energy sources are used across households, leading to inaccurate representations of energy costs across states. For example, the data combines the cost of heating oil with natural gas costs, even though households using heating oil presumably will not be using natural gas for heating. This would not be a problem if the numbers were adjusted to overall household averages, but WalletHub puts in the full cost for each energy source as if each household used this full amount. This mixing of different energy sources skews the results and does not give a proper comparison of household energy expenses.

As a result, the WalletHub tables show Wyoming with the highest energy costs primarily because they also show this state with the highest monthly home heating oil costs at $362. But the 2021 American Community Survey reports that only 0.1% of all occupied housing units in Wyoming use this energy source for heating. Therefore, a more accurate entry based on the total household average in this state would instead be $0.36. The table further misses other heating fuels such as wood and propane, which accounts for 16.0% of housing units in Wyoming and 5.3% in California.

4. There’s More to the Story, Other Energy Costs Not Included: The numbers used in the WalletHub study are already changing. In California, electricity prices continue to surge, already causing the state to have the 13th highest electricity bill in 2023, up from 18th highest in 2022. Electricity costs will rise even higher as households are pushed off natural gas by state and local policies and become more reliant on more costly electrical heat. Gasoline and diesel prices have also risen due to increased state fuel taxes on July 1, and vehicle miles traveled are continuing to recover from the enforced pandemic pause, which is driving up the cost of these energy sources.

In addition, the WalletHub table does not cover all energy costs. Not included are households reliant on propane, particularly mobile homes and households in rural areas. Also not incorporated are costs of distributed energy such as solar panels, which may have lower operating costs but are not cost-free when considering acquisition and installation of panels and batteries, annual maintenance, required replacement, and the shifting state picture on tariffs.

5. Significant Regional Energy Differences Ignored: The WalletHub data only considers state averages, overlooking the significant differences between regions in California. Coastal households have lower energy needs due to milder weather, but they also have higher incomes which allow them to evade the cost consequences of the state’s energy policies by installing solar panels and batteries to bypass if not profit off of rising electricity rates, using electric vehicles to avoid rising fuel prices, and telecommuting to avoid fuels altogether.

In contrast, energy demand is significantly higher in the more climate variable and lower income interior regions of California. On a regional basis using Energy Commission [[link removed]] data, average household electricity use was as much as 85% higher in the state’s interior regions compared to the lowest use coastal area in 2021, and costs using average county residential rates were as much as 104% higher. Natural gas—which varies more by availability—ranges up to as much as nine times higher in the Central Valley compared to other parts of the state.

State Policies and Energy Affordability

In previous eras of lower energy prices, California’s climate and housing affordability near jobs combined to reduce the burden of energy costs. However, rising energy prices driven by state policies have reversed this situation. The extent of how much can be illustrated in the following exercise.

The table below considers a scenario where California’s energy consumption is unchanged. Instead of using California’s current energy prices, however, they are replaced using the averages faced by households in the other states – prices that consequently are achievable if the current energy policies of California were not in place. As indicated, by shifting state policies to focus on costs as well, energy in California would become more affordable and in fact align with the levels contained in the otherwise seriously flawed WalletHub piece.

The lesson from this example is simple. Energy use is not affecting its affordability in California. The unique circumstances and climate here still make that possible. Energy prices as now being driven ever higher by state policies are the problem, and it is now costing California households an extra $22.2 billion a year in direct costs above the average in other states and more when considering the effect of high energy costs on prices for other goods and services in the state.

Total Cost of State Energy Policies

Our Math

In our continuing attempt to bring accurate data to these issues, we constructed our own comparison table. A detailed description of how each element was calculated follows this table. In all cases, the specific data source is cited, with most of this information also available through the Center’s on-line data series [[link removed]] for those wishing to calculate alongside us.

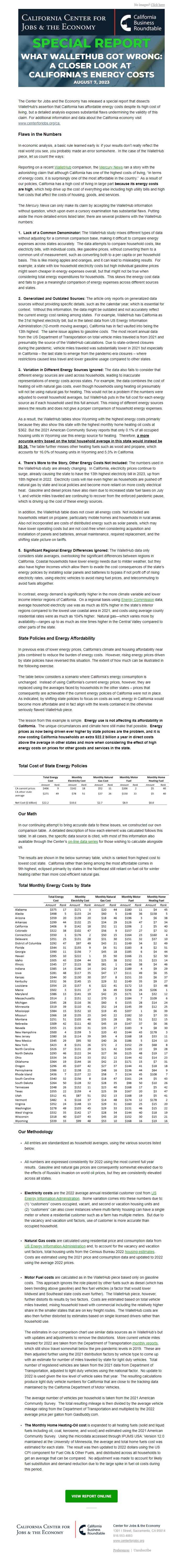

The results are shown in the below summary table, which is ranked from highest cost to lowest cost state. California rather than being among the most affordable comes in 9th highest, eclipsed primarily by states in the Northeast still reliant on fuel oil for winter heating rather than more cost-efficient natural gas.

Total Monthly Energy Costs by State

Our Methodology

All entries are standardized as household averages, using the various sources listed below. All numbers are expressed consistently for 2022 using the most current full year results. Gasoline and natural gas prices are consequently somewhat elevated due to the effects of Russia’s invasion on world oil prices, but they are consistently elevated across all states. Electricity costs are the 2022 average annual residential customer cost from US Energy Information Administration [[link removed]]. Some variation comes into these numbers due to: (1) “customers” covers occupied, vacant, and second or vacation housing units and (2) “customers” can also cover instances where multi-family housing can have a single meter or where a residential customer such as a farm has multiple meters. But due to the vacancy and vacation unit factors, use of customer is more accurate than occupied household. Natural Gas costs are calculated using residential price and consumption data from US Energy Information Administration [[link removed]] and, to account for the vacancy and vacation unit factors, total housing units from the Census Bureau 2022 housing estimates [[link removed]]. Costs are estimated using the 2021 price and consumption data and updated to 2022 using the average 2022 prices.

Motor Fuel costs are calculated as in the WalletHub piece based only on gasoline costs. This approach ignores the role played by other fuels such as diesel (which has been trending above gasoline) and flex fuel vehicles (a factor that would lower Midwest and Southeast state costs even further). The WalletHub piece, however, further distorts its results by two factors. Costs are estimated based on total vehicle miles traveled, mixing household travel with commercial including the relatively higher share in the smaller states that are on key freight routes. The WalletHub costs are also then further distorted by estimates based on single licensed drivers rather than household use.

The estimates in our comparison chart use similar data sources as in WalletHub’s but with updates and adjustments to remove the distortions. More current vehicle miles traveled for 2022 are taken from the Department of Transportation monthly reports [[link removed]], which still show travel somewhat below the pre-pandemic levels in 2019. These are then adjusted further using the 2021 distribution factors by vehicle type to come up with an estimate for number of miles traveled by state for light duty vehicles. Total number of registered vehicles are taken from the 2021 data from Department of Transportation, adjusted to light duty vehicles using the national factor. No update to 2022 is used given the low level of vehicle sales that year. The resulting calculations produce light duty vehicle numbers for California that are close to the tracking data maintained by the California Department of Motor Vehicles.

The average number of vehicles per household is taken from the 2021 American Community Survey. The total resulting mileage is then divided by the average vehicle mileage rating from the Department of Transportation and multiplied by the 2022 average price per gallon from GasBuddy.com.

The Monthly Home Heating-Oil cost is expanded to all heating fuels (solid and liquid fuels including oil, coal, kerosene, and wood) and estimated using the 2021 American Community Survey. Using the microdata accessed through IPUMS USA: Version 12.0 maintained at the University of Minnesota, the average and total home fuels cost was estimated for each state. The result was then updated to 2022 dollars using the US CPI component for Fuel Oils & Other Fuels, and distributed across all households to get an average that can be compared. No adjustment was made to account for likely fuel substitution and demand reduction due to the large spike in fuel oil costs during this period. VIEW REPORT ONLINE [[link removed]]

Center for Jobs & the Economy

1301 I Street, Sacramento, CA 95814

916.553.4093

[[link removed]]

Preferences [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed]

The Center for Jobs and the Economy has released a special report that dissects WalletHub's assertion that California has affordable energy costs despite its high cost of living, but a detailed analysis exposes substantial flaws undermining the validity of this claim. For additional information and data about the California economy visit [[link removed].]

Flaws in the Numbers

In economic analysis, a basic rule learned early is: if your results don’t really reflect the real world you see, you probably made an error somewhere. In the case of the WalletHub piece, let us count the ways:

Reporting on a recent WalletHub [[link removed]] comparison, the Mercury News [[link removed]] ran a story with the astonishing claim that although California has one of the highest costs of living, “in terms of energy costs, it is surprisingly one of the most affordable in the country.” As a result of our policies, California has a high cost of living in large part because its energy costs are high, which help drive up the cost of everything else including high utility bills and high fuel costs that affect the costs of housing, goods, and services.

The Mercury News can only make its claim by accepting the WalletHub information without question, which upon even a cursory examination has substantial flaws. Putting aside the more detailed errors listed later, there are several problems with the WalletHub numbers:

1. Lack of a Common Denominator: The WalletHub study mixes different types of data without adjusting for a common comparison base, making it difficult to compare energy expenses across states accurately. The data attempts to compare household costs, like electricity bills, with individual costs, like gasoline prices, without converting them to a common unit of measurement, such as converting both to a per capita or per household basis. This is like mixing apples and oranges, and it can lead to misleading results. For example, a state with low household electricity costs but high individual gasoline prices might seem cheaper in energy expenses overall, but that might not be true when considering total energy expenditures for households. This skews the energy cost data and fails to give a meaningful comparison of energy expenses across different sources and states.

2. Generalized and Outdated Sources: The article only reports on generalized data sources without providing specific details, such as the calendar year, which is essential for context. Without this information, the data might be outdated and not accurately reflect the current energy cost ranking among states. For example, WalletHub has California as the 31st highest electricity bill, but in the latest data from US Energy Information Administration (12-month moving average), California has in fact vaulted into being the 13th highest. The same issue applies to gasoline costs. The most recent annual data from the US Department of Transportation on total vehicle miles traveled is from 2021 and presumably the source of the WalletHub calculations. Due to state-ordered closures during the pandemic, vehicle miles traveled was substantially lower in 2021 but especially in California – the last state to emerge from the pandemic-era closures – where restrictions caused less travel and lower gasoline usage compared to other states.

3. Variation in Different Energy Sources Ignored: The data also fails to consider that different energy sources are used across households, leading to inaccurate representations of energy costs across states. For example, the data combines the cost of heating oil with natural gas costs, even though households using heating oil presumably will not be using natural gas for heating. This would not be a problem if the numbers were adjusted to overall household averages, but WalletHub puts in the full cost for each energy source as if each household used this full amount. This mixing of different energy sources skews the results and does not give a proper comparison of household energy expenses.

As a result, the WalletHub tables show Wyoming with the highest energy costs primarily because they also show this state with the highest monthly home heating oil costs at $362. But the 2021 American Community Survey reports that only 0.1% of all occupied housing units in Wyoming use this energy source for heating. Therefore, a more accurate entry based on the total household average in this state would instead be $0.36. The table further misses other heating fuels such as wood and propane, which accounts for 16.0% of housing units in Wyoming and 5.3% in California.

4. There’s More to the Story, Other Energy Costs Not Included: The numbers used in the WalletHub study are already changing. In California, electricity prices continue to surge, already causing the state to have the 13th highest electricity bill in 2023, up from 18th highest in 2022. Electricity costs will rise even higher as households are pushed off natural gas by state and local policies and become more reliant on more costly electrical heat. Gasoline and diesel prices have also risen due to increased state fuel taxes on July 1, and vehicle miles traveled are continuing to recover from the enforced pandemic pause, which is driving up the cost of these energy sources.

In addition, the WalletHub table does not cover all energy costs. Not included are households reliant on propane, particularly mobile homes and households in rural areas. Also not incorporated are costs of distributed energy such as solar panels, which may have lower operating costs but are not cost-free when considering acquisition and installation of panels and batteries, annual maintenance, required replacement, and the shifting state picture on tariffs.

5. Significant Regional Energy Differences Ignored: The WalletHub data only considers state averages, overlooking the significant differences between regions in California. Coastal households have lower energy needs due to milder weather, but they also have higher incomes which allow them to evade the cost consequences of the state’s energy policies by installing solar panels and batteries to bypass if not profit off of rising electricity rates, using electric vehicles to avoid rising fuel prices, and telecommuting to avoid fuels altogether.

In contrast, energy demand is significantly higher in the more climate variable and lower income interior regions of California. On a regional basis using Energy Commission [[link removed]] data, average household electricity use was as much as 85% higher in the state’s interior regions compared to the lowest use coastal area in 2021, and costs using average county residential rates were as much as 104% higher. Natural gas—which varies more by availability—ranges up to as much as nine times higher in the Central Valley compared to other parts of the state.

State Policies and Energy Affordability

In previous eras of lower energy prices, California’s climate and housing affordability near jobs combined to reduce the burden of energy costs. However, rising energy prices driven by state policies have reversed this situation. The extent of how much can be illustrated in the following exercise.

The table below considers a scenario where California’s energy consumption is unchanged. Instead of using California’s current energy prices, however, they are replaced using the averages faced by households in the other states – prices that consequently are achievable if the current energy policies of California were not in place. As indicated, by shifting state policies to focus on costs as well, energy in California would become more affordable and in fact align with the levels contained in the otherwise seriously flawed WalletHub piece.

The lesson from this example is simple. Energy use is not affecting its affordability in California. The unique circumstances and climate here still make that possible. Energy prices as now being driven ever higher by state policies are the problem, and it is now costing California households an extra $22.2 billion a year in direct costs above the average in other states and more when considering the effect of high energy costs on prices for other goods and services in the state.

Total Cost of State Energy Policies

Our Math

In our continuing attempt to bring accurate data to these issues, we constructed our own comparison table. A detailed description of how each element was calculated follows this table. In all cases, the specific data source is cited, with most of this information also available through the Center’s on-line data series [[link removed]] for those wishing to calculate alongside us.

The results are shown in the below summary table, which is ranked from highest cost to lowest cost state. California rather than being among the most affordable comes in 9th highest, eclipsed primarily by states in the Northeast still reliant on fuel oil for winter heating rather than more cost-efficient natural gas.

Total Monthly Energy Costs by State

Our Methodology

All entries are standardized as household averages, using the various sources listed below. All numbers are expressed consistently for 2022 using the most current full year results. Gasoline and natural gas prices are consequently somewhat elevated due to the effects of Russia’s invasion on world oil prices, but they are consistently elevated across all states. Electricity costs are the 2022 average annual residential customer cost from US Energy Information Administration [[link removed]]. Some variation comes into these numbers due to: (1) “customers” covers occupied, vacant, and second or vacation housing units and (2) “customers” can also cover instances where multi-family housing can have a single meter or where a residential customer such as a farm has multiple meters. But due to the vacancy and vacation unit factors, use of customer is more accurate than occupied household. Natural Gas costs are calculated using residential price and consumption data from US Energy Information Administration [[link removed]] and, to account for the vacancy and vacation unit factors, total housing units from the Census Bureau 2022 housing estimates [[link removed]]. Costs are estimated using the 2021 price and consumption data and updated to 2022 using the average 2022 prices.

Motor Fuel costs are calculated as in the WalletHub piece based only on gasoline costs. This approach ignores the role played by other fuels such as diesel (which has been trending above gasoline) and flex fuel vehicles (a factor that would lower Midwest and Southeast state costs even further). The WalletHub piece, however, further distorts its results by two factors. Costs are estimated based on total vehicle miles traveled, mixing household travel with commercial including the relatively higher share in the smaller states that are on key freight routes. The WalletHub costs are also then further distorted by estimates based on single licensed drivers rather than household use.

The estimates in our comparison chart use similar data sources as in WalletHub’s but with updates and adjustments to remove the distortions. More current vehicle miles traveled for 2022 are taken from the Department of Transportation monthly reports [[link removed]], which still show travel somewhat below the pre-pandemic levels in 2019. These are then adjusted further using the 2021 distribution factors by vehicle type to come up with an estimate for number of miles traveled by state for light duty vehicles. Total number of registered vehicles are taken from the 2021 data from Department of Transportation, adjusted to light duty vehicles using the national factor. No update to 2022 is used given the low level of vehicle sales that year. The resulting calculations produce light duty vehicle numbers for California that are close to the tracking data maintained by the California Department of Motor Vehicles.

The average number of vehicles per household is taken from the 2021 American Community Survey. The total resulting mileage is then divided by the average vehicle mileage rating from the Department of Transportation and multiplied by the 2022 average price per gallon from GasBuddy.com.

The Monthly Home Heating-Oil cost is expanded to all heating fuels (solid and liquid fuels including oil, coal, kerosene, and wood) and estimated using the 2021 American Community Survey. Using the microdata accessed through IPUMS USA: Version 12.0 maintained at the University of Minnesota, the average and total home fuels cost was estimated for each state. The result was then updated to 2022 dollars using the US CPI component for Fuel Oils & Other Fuels, and distributed across all households to get an average that can be compared. No adjustment was made to account for likely fuel substitution and demand reduction due to the large spike in fuel oil costs during this period. VIEW REPORT ONLINE [[link removed]]

Center for Jobs & the Economy

1301 I Street, Sacramento, CA 95814

916.553.4093

[[link removed]]

Preferences [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: California Center for Jobs and the Economy

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: California

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor