|

The Vegan Movement Has Failed. It's Time to Build a Movement for Rescue.

A recent MIT study is the latest evidence that vegan consumer advocacy can backfire. But there's something we can do instead of making vegans: rescue the animals.

What’s up this week

A study published by the MIT Media Lab showed the “vegan” label can backfire – but there’s still great hope for animal rights. That hope, however, lies in alternatives to consumer advocacy such as open rescue. There are two primary reasons for this: first, open rescue, unlike consumer advocacy, is a powerful engine for so-called cognitive liberation; second, open rescue dramatically expands the potential pool of support for animal rights. I explain why in today’s newsletter below.

This weekend, I’ll be hosting a conversation with open rescue pioneer Adam Durand, on what he learned from going to jail for rescuing animals. Adam’s work inspired people across the nation to witness the reality of egg farming, but his successful prosecution chilled the movement for rescue. As the Sonoma Rescue Trial approaches, I’ll be asking him: what can we do this time? Don’t miss the event.

The threats posed by animal agriculture have been in the news this week. First, Nature published a groundbreaking study of over 55,000 consumers and concluded that “the relationship between environmental impact and animal-based food consumption is clear and should prompt the reduction of the latter.” Then the New York Times published an article on the pandemic risks posed by even small-scale animal agriculture, such as a county fair, on our local communities.

A disturbing image of pilot whales grouping up near the shoreline, in a heart shape, went viral this week. Shortly after this image was shot, the group of whales beached and more than 50 died. There has been great speculation as to the cause of this behavior, but above all, it shows the mystery of life.

It’s hard for me to believe it, but we are just over on month away from my felony trail in Sonoma County - and just a couple weeks away from the mini summit we’re organizing to prepare. We’ve faced huge obstacles. And I’ve had to pivot almost my entire life towards preparing for this case. But it is the most important one yet, because of both its legal significance and the storylines we expect to unfold in the media. There will be one more chance for our supporters and advocates to get plugged into the case – and learn how you can harness it to push for animal rights. It’s the Open Rescue Leadership Summit unfolding in Berkeley from Aug 12-13 in a couple weeks.

The problem with consumer activism

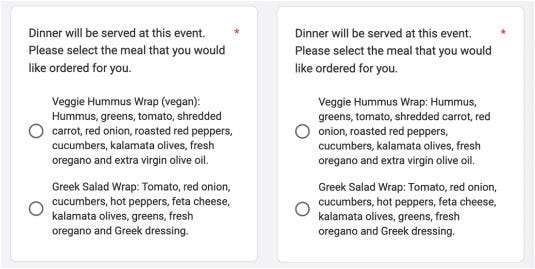

This week, the MIT Media Lab published a randomized controlled trial testing the impact of the word “vegan” on a person’s willingness to try a vegan product. The study was conducted among registrants to events at the Media Lab, where free food was provided. Registrants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: the labeled condition, where a vegan option was labeled with that word; and the non-labeled condition, where exactly the same option was presented but without the word vegan.

And, shockingly, the two conditions had dramatically different results, with the option labeled “vegan” being chosen at about half the rate as the same option without the label. While the study has many significant limitations, it’s only the latest in a long line of evidence showing that the vegan movement simply hasn’t succeeded. Take, for example, some of the following data:

Veganism, accordingly to unbiased polls, is not growing. Gallup, the nation’s most well-known polling agency, found that the percentage of vegans and vegetarians is mostly unchanged since 2012.

Veganism has a terrible public relations problem, to the point that Vox penned an article, “Why do people hate vegans so much?” Surveys have regularly shown that most non-vegans have strong negative attitudes towards vegans, worse than atheists or immigrants.

Per capita meat consumption has been growing steadily in the last decade. The National Chicken Council estimates that it has gone up from 200.2 pounds person in 2012 to 226.8 in 2022.

Top alternative meat companies are struggling mightily. After a brief surge around the pandemic, the largest alt-meat companies are facing serious headwinds, including Beyond Meat and Impossible.

Most vegans and animal advocates don’t think, or even know, about this data. And yet it paints a disturbing picture for the future of animal rights, to the extent we have linked our future to the vegan movement. And through most of the animal rights movement’s recent history, that linkage is hardly even a question; veganism and animal rights are considered one and the same.

There was, however, one obscure, poorly-written article published in 2007 that questioned this connection. And while the article received much hate, it has had a life that goes far beyond what anyone, including the author, could have predicted.

I know this because I am the author.

Adventures in boycotting veganism

In 2007, motivated by my readings in social movement research, I penned an article with an infamous title: Boycott Veganism. The title was clickbait. I was not, in fact, boycotting veganism but arguing that consumer activism was insufficient to create social change. The fact that I was not defending the consumption of animals was clear from the subtitle: “Animal rights only begins with your diet.” But very few people read beyond the title on the forums in which I circulated the piece for feedback.

Instead, they came after me. Hard.

Multiple vegan forums exploded with angry responses after I posted an early draft. I was criticized for being oppressive, arrogant, traitorous, and – most commonly – downright stupid. “Why is this dumbass posting this article on a vegan forum?” was the typical response. And I was banned from a number of vegan spaces, including one — Vegan Represent — that I had been a regular contributor to, for many years.

But something strange happened, over time. A small number of people actually read the article, rather than just the headline. And many were swayed by the logic. Two points were key. First, I argued that the veganism, as a narrative strategy, could not inspire people to anger or hope - the key ingredients to social change. Its meaning is too incoherent – with as many purposes (environmental, health, spiritual) as there are vegans – and its framing too bland to inspire the sort of mass movement that animal rights would require. Second, by focusing on a relatively marginal dietary identity, the vegan movement had a natural ceiling. It would never get the numbers needed for true social or political power.

What we needed, I argued, was something different: direct action. Giving aid to animals directly was the right narrative strategy because it focused on animal cruelty, and our ability to stop it. Unlike veganism, it had the power to enrage and inspire. And direct action could expand the scope of the movement’s support, by focusing on identities (e.g., animal lovers, families with pets) that were much larger and influential than vegan consumers. It was a movement strategy that could mobilize the masses, rather than just a small dietary niche.

The founder of Vegan Represent forum which banned me, Dave Sutherland, became one of the article’s biggest advocate. Though I never published Boycott Veganism, the piece went mini-viral on various online platforms — Reddit, Tumblr — between 2007 and 2013 due to the work of Dave and other fans of the piece. And every time the article sprouted up, while there would be come converts, there would be a new round of hate.

Until 2014, the year the movement seemingly turned.

Much ado about vegan leafleting

In the early 2010s, effective altruism (EA) was just beginning to capture the attention of animal advocates. A few high-net worth individuals within the EA space began to contribute massive amounts of money to farm animal advocacy, shifting the nature of the movement. And the number 1 intervention that was recommended, at the time, was vegan leafleting. The techno-libertarian ethos of EA made a focus on consumers, market, and money a natural fit. And vegan consumer activism also fit well with the EA focus on measurable results.

But EA also brought something else into the animal rights space: an emphasis on evidence and data. And that presented an opening for someone like me. While I had long abandoned my Ph.D. in economics, I had been trained by some of the greatest experimental social scientists in history at MIT. The mantra of the department was “I won’t believe what you had for lunch today unless you present me the data.” And each of the students at MIT was compelled to learn statistical and experimental methods, as part of our training.

And anyone with training of that sort could see pretty clearly that the EA and animal rights consensus of the early 2010s, around vegan outreach, was clearly wrong. I penned a blog post in 2013 to explain why. But, in a nutshell, the consensus was based on analysis that was “science-y” — clothed in the language of science, but lacking scientific rigor. A closer examination of good scientific research around leafleting and other forms of so-called impersonal outreach, i.e., trying to persuade someone you have no other relationship with, showed dismal results.

The Science or Science-y blog post, like Boycott Veganism, generated an enormous amount of hate. The leaders of a few prominent animal rights organizations called me a mole for the meat industry, publicly, and would tell everyone they met at animal rights conferences that I was damaging the movement. But as with Boycott Veganism, the critique gained a following. A prominent (non-vegan) effective altruist thinker, Jeff Kaufman, began to question the conventional wisdom on the effectiveness of vegan advocacy. And the leaders of Animal Charity Evaluators, a prominent EA organization that had been extremely hostile towards my work (and towards me personally, for reasons I never fully understood) eventually ran a study in 2017 showing that vegan outreach probably had no effect at all.

That left the movement in a tough spot, after years of focusing on outreach above all other interventions. What do we do instead?

The move to systems

The answer, I argued, was based on a growing body of research that has been the subject of multiple Nobel Prizes: focus on systems, rather than individuals. The idea of a system is a bit convoluted in public discourse. And there is a huge amount of very complicated math at the root of systems analysis, including the most cited paper in the history of sociology (which was written by a mathematician and a physicist!). But the basic idea behind systems analysis is actually quite simple:

We are more than the sum of our individual parts.

Let me unpack this. The problem with vegan consumer advocacy was that it focused entirely on individual change. But if individuals are not the driving forces of human society, but the interactions and norms and policies that exists between individuals, then the focus on individuals is bound to fail. To create change, we needed to shift our focus to these networks and interactions, rather than individuals.

This was the shift that began to happen, in both the animal rights and environmental movements, in the early 2010s. And it has led to historic results for both movements — and a resurgence in political power. Among other systemic approaches, we have seen enormous success in corporate campaigns, focusing on animal welfare policies at powerful institutions; groundbreaking legislative campaigns, including bans on gestation crates across the nation and even a complete ban on fur in California; and, perhaps most importantly, shifts in social norms driven by changes in public discourse. There have been more opinion pieces in top mainstream news outlets in the last 5 years, arguing for animal rights, than I had seen in my prior 15 years of animal rights activism combined. And it’s not even close.

But there is one particular strategy and tactic, more than any other, that I believe will be the greatest driver of change. My belief, moreover, is not based on anecdotes or personal experience, but by the evidence from history. That strategy is the strategy of rescue. And if we build a movement for rescue, it matters not at all how many vegan consumers we have.

The movement for rescue

I have written extensively about why rescue is so crucial to change for animal rights. It is the strongest narrative battleground for us to push for change, because it focuses on individuals, and in the most dire and sympathetic circumstances. It allows us to overcome huge obstacles in other efforts at systemic change, like regulatory capture and inertia, and force the issue in our political system in dramatic, radical, and shockingly successful ways. And, above all, it links our movement’s incentives, and its spirit, more directly to the victims. It solves the “alignment problem” of animal rights, by keeping those who represent the animals close to the problem.

And there is plenty of data to back up these arguments. Open rescue has been crucial to previous surges in animal rights; indeed, it’s almost as if the movement for rescue is on a clock, waiting ten years to inspire the next wave! In my own activism, open rescues have generated more attention and mobilization than all the rest of my activism combined. This is why, despite the seriousness of the charges before me, I am looking forward to the Sonoma Rescue trial as an opportunity for change, and not just a personal life hazard.

But two things need to happen for us to continue to drive, not just rescue, but all efforts at systemic change.

The first is that we have to build a worthy and unified movement. The renowned social movement scholar Charles Tilly wrote many decades ago that movements that changed entire systems, like the Civil Rights Movement, were WUNC — worthy, unified, numerous, and committed. But, in my view, WUNC can almost be reduced to its first two letters, WU, because a movement that is worthy and unified will become numerous and committed. Right now, the animal rights movement is exhibiting neither of those characteristics.

Far from being “eloquent” and “disciplined” – the defining features of worthiness for Tilly – the movement relies too much on amateur and even trollish messaging, with no clear strategic purpose. And far from being unified, the movement is constantly divided by infighting. The internal disputes within DxE, which are part of the reason I recently left the organization, are one such example. But there are many others, no doubt partly instigated by forces within the industry.

The second crucial factor is that need a movement that is brave. High risk activism has always been a key part of social movements. With no risk, there is no change. And movements historically have cultivated and honored their most courageous adherents. But today, that seems to have almost completely changed. Even within activist movements, people fight over greater claims to vulnerability and victimhood, not courage. Social status accrues to the parties that win this race to the bottom. Resilience, strength, and bravery, in contrast, are practically looked down upon. That has to change, if movements are going to take on powerful systems and win.

There is so much more I could write about, both in why these factors are crucial, and how we can build a movement that exhibits them. But I’ll end by saying that I don’t actually have all the answers. We’re going to have to figure them out together.

I hope I’ll see you this Sunday, and at the Open Rescue Leadership Summit, so we can do that.