| From | xxxxxx <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Harassment Against Scientists Is Out of Control |

| Date | July 1, 2023 12:00 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

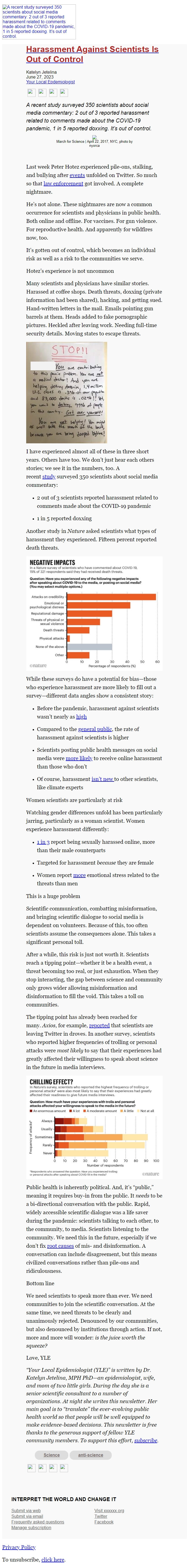

[A recent study surveyed 350 scientists about social media

commentary: 2 out of 3 reported harassment related to comments made

about the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 in 5 reported doxxing. It’s out of

control.]

[[link removed]]

HARASSMENT AGAINST SCIENTISTS IS OUT OF CONTROL

[[link removed]]

Katelyn Jetelina

June 27, 2023

Your Local Epdemiologist

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ A recent study surveyed 350 scientists about social media

commentary: 2 out of 3 reported harassment related to comments made

about the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 in 5 reported doxxing. It’s out of

control. _

March for Science | April 22, 2017, NYC, photo by nyorca

Last week Peter Hotez experienced pile-ons, stalking, and bullying

after events

[[link removed]] unfolded

on Twitter. So much so that law enforcement

[[link removed]] got

involved. A complete nightmare.

He’s not alone. These nightmares are now a common occurrence for

scientists and physicians in public health. Both online and offline.

For vaccines. For gun violence. For reproductive health. And

apparently for wildfires now, too.

It’s gotten out of control, which becomes an individual risk as well

as a risk to the communities we serve.

Hotez’s experience is not uncommon

Many scientists and physicians have similar stories. Harassed at

coffee shops. Death threats, doxxing (private information had been

shared), hacking, and getting sued. Hand-written letters in the mail.

Emails pointing gun barrels at them. Heads added to fake pornographic

pictures. Heckled after leaving work. Needing full-time security

details. Moving states to escape threats.

[[link removed]]

I have experienced almost all of these in three short years. Others

have too. We don’t just hear each others stories; we see it in the

numbers, too. A recent study

[[link removed]] surveyed

350 scientists about social media commentary:

*

2 out of 3 scientists reported harassment related to comments made

about the COVID-19 pandemic

*

1 in 5 reported doxxing

Another study in _Nature_ asked scientists what types of harassment

they experienced. Fifteen percent reported death threats.

[[link removed]]

While these surveys do have a potential for bias—those who

experience harassment are more likely to fill out a survey—different

data angles show a consistent story:

*

Before the pandemic, harassment against scientists wasn’t nearly

as high

[[link removed]]

*

Compared to the general public

[[link removed]],

the rate of harassment against scientists is higher

*

Scientists posting public health messages on social media were more

likely

[[link removed]] to

receive online harassment than those who don’t

*

Of course, harassment isn’t new

[[link removed]]to other

scientists, like climate experts

Women scientists are particularly at risk

Watching gender differences unfold has been particularly jarring,

particularly as a woman scientist. Women experience harassment

differently:

*

1 in 3

[[link removed]] report

being sexually harassed online, more than their male counterparts

*

Targeted for harassment _because_ they are female

*

Women report more

[[link removed]] emotional

stress related to the threats than men

This is a huge problem

Scientific communication, combatting misinformation, and bringing

scientific dialogue to social media is dependent on volunteers.

Because of this, too often scientists assume the consequences alone.

This takes a significant personal toll.

After a while, this risk is just not worth it. Scientists reach a

tipping point—whether it be a health event, a threat becoming too

real, or just exhaustion. When they stop interacting, the gap between

science and community only grows wider allowing misinformation and

disinformation to fill the void. This takes a toll on communities.

The tipping point has already been reached for many. _Axios_, for

example, reported

[[link removed]] that

scientists are leaving Twitter in droves. In another survey,

scientists who reported higher frequencies of trolling or personal

attacks were _most likely_ to say that their experiences had greatly

affected their willingness to speak about science in the future in

media interviews.

[[link removed]]

Public health is inherently political. And, it’s “public,”

meaning it requires buy-in from the public. It _needs_ to be a

bi-directional conversation with the public. Rapid, widely accessible

scientific dialogue was a life saver during the pandemic: scientists

talking to each other, to the community, to media. Scientists

listening to the community. We need this in the future, especially if

we don’t fix root causes

[[link removed]] of

mis- and disinformation. A conversation can include disagreement, but

this means civilized conversations rather than pile-ons and

ridiculousness.

Bottom line

We need scientists to speak more than ever. We need communities to

join the scientific conversation. At the same time, we need threats to

be clearly and unanimously rejected. Denounced by our communities, but

also denounced by institutions through action. If not, more and more

will wonder: _is the juice worth the squeeze?_

Love, YLE

_“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn

Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little

girls. During the day she is a senior scientific consultant to a

number of organizations. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main

goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so

that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions.

This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE

community members. To support this effort, subscribe

[[link removed]]._

* Science

[[link removed]]

* anti-science

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

commentary: 2 out of 3 reported harassment related to comments made

about the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 in 5 reported doxxing. It’s out of

control.]

[[link removed]]

HARASSMENT AGAINST SCIENTISTS IS OUT OF CONTROL

[[link removed]]

Katelyn Jetelina

June 27, 2023

Your Local Epdemiologist

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ A recent study surveyed 350 scientists about social media

commentary: 2 out of 3 reported harassment related to comments made

about the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 in 5 reported doxxing. It’s out of

control. _

March for Science | April 22, 2017, NYC, photo by nyorca

Last week Peter Hotez experienced pile-ons, stalking, and bullying

after events

[[link removed]] unfolded

on Twitter. So much so that law enforcement

[[link removed]] got

involved. A complete nightmare.

He’s not alone. These nightmares are now a common occurrence for

scientists and physicians in public health. Both online and offline.

For vaccines. For gun violence. For reproductive health. And

apparently for wildfires now, too.

It’s gotten out of control, which becomes an individual risk as well

as a risk to the communities we serve.

Hotez’s experience is not uncommon

Many scientists and physicians have similar stories. Harassed at

coffee shops. Death threats, doxxing (private information had been

shared), hacking, and getting sued. Hand-written letters in the mail.

Emails pointing gun barrels at them. Heads added to fake pornographic

pictures. Heckled after leaving work. Needing full-time security

details. Moving states to escape threats.

[[link removed]]

I have experienced almost all of these in three short years. Others

have too. We don’t just hear each others stories; we see it in the

numbers, too. A recent study

[[link removed]] surveyed

350 scientists about social media commentary:

*

2 out of 3 scientists reported harassment related to comments made

about the COVID-19 pandemic

*

1 in 5 reported doxxing

Another study in _Nature_ asked scientists what types of harassment

they experienced. Fifteen percent reported death threats.

[[link removed]]

While these surveys do have a potential for bias—those who

experience harassment are more likely to fill out a survey—different

data angles show a consistent story:

*

Before the pandemic, harassment against scientists wasn’t nearly

as high

[[link removed]]

*

Compared to the general public

[[link removed]],

the rate of harassment against scientists is higher

*

Scientists posting public health messages on social media were more

likely

[[link removed]] to

receive online harassment than those who don’t

*

Of course, harassment isn’t new

[[link removed]]to other

scientists, like climate experts

Women scientists are particularly at risk

Watching gender differences unfold has been particularly jarring,

particularly as a woman scientist. Women experience harassment

differently:

*

1 in 3

[[link removed]] report

being sexually harassed online, more than their male counterparts

*

Targeted for harassment _because_ they are female

*

Women report more

[[link removed]] emotional

stress related to the threats than men

This is a huge problem

Scientific communication, combatting misinformation, and bringing

scientific dialogue to social media is dependent on volunteers.

Because of this, too often scientists assume the consequences alone.

This takes a significant personal toll.

After a while, this risk is just not worth it. Scientists reach a

tipping point—whether it be a health event, a threat becoming too

real, or just exhaustion. When they stop interacting, the gap between

science and community only grows wider allowing misinformation and

disinformation to fill the void. This takes a toll on communities.

The tipping point has already been reached for many. _Axios_, for

example, reported

[[link removed]] that

scientists are leaving Twitter in droves. In another survey,

scientists who reported higher frequencies of trolling or personal

attacks were _most likely_ to say that their experiences had greatly

affected their willingness to speak about science in the future in

media interviews.

[[link removed]]

Public health is inherently political. And, it’s “public,”

meaning it requires buy-in from the public. It _needs_ to be a

bi-directional conversation with the public. Rapid, widely accessible

scientific dialogue was a life saver during the pandemic: scientists

talking to each other, to the community, to media. Scientists

listening to the community. We need this in the future, especially if

we don’t fix root causes

[[link removed]] of

mis- and disinformation. A conversation can include disagreement, but

this means civilized conversations rather than pile-ons and

ridiculousness.

Bottom line

We need scientists to speak more than ever. We need communities to

join the scientific conversation. At the same time, we need threats to

be clearly and unanimously rejected. Denounced by our communities, but

also denounced by institutions through action. If not, more and more

will wonder: _is the juice worth the squeeze?_

Love, YLE

_“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn

Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little

girls. During the day she is a senior scientific consultant to a

number of organizations. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main

goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so

that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions.

This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE

community members. To support this effort, subscribe

[[link removed]]._

* Science

[[link removed]]

* anti-science

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- L-Soft LISTSERV