'Millennials Moved Right': NYT Cherry-Picks Data to Bolster Political Folklore

David W. Moore

The New York Times' Nate Cohn (6/1/23) demonstrates how to select two data points that match your preconceived hypothesis.

New York Times polling analyst Nate Cohn (6/1/23) claimed, “Millennials Are Not an Exception. They’ve Moved to the Right.”

His piece was a rebuttal to an article last December by John Burn-Murdoch (Financial Times, 12/30/22), who argued that “Millennials are Shattering the Oldest Rule in Politics.” How? “Generations of voters...are no longer moving to the right as they age.”

That “oldest rule in politics,” as Burn-Murdoch writes, or what Cohn refers to as “political folklore,” is the notion that as people age, they naturally tend to become more conservative.

There are many ways to frame that notion, which has been attributed to several different leaders over the centuries, such as John Adams, Edmund Burke, Victor Hugo, King Oscar II of Sweden, George Bernard Shaw, Benjamin Disraeli and Winston Churchill. Here is one phrasing: “If you are not a liberal at 25, you have no heart. If you are not a conservative at 35, you have no brain.”

'Not necessarily stunning'

Cohn's initial piece (6/1/23) left out the strong shift toward the Democrats of voters born before 1960—which would have undermined his claim that "voters become more conservative as they get older."

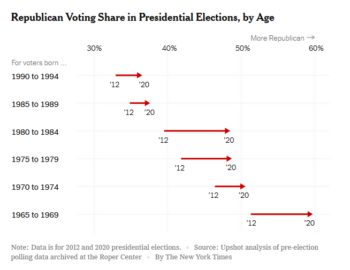

Cohn referenced the truism as an explanation for his finding that three groups of millennials (those born in 1980–84, 1985–89 and 1990–94) all voted more Republican in 2020 than they did in 2012. In addition, he wrote, not only those groups, but three older cohorts of voters—those born in 1965–69, 1970–74, and 1975–79—also shifted toward the Republican Party in 2020.

Just after presenting these figures, Cohn wrote: “It’s not necessarily a stunning finding. Political folklore has long held that voters become more conservative as they get older.”

Well, yeah. The folklore has been around a long time. But cherry-picking data to support this preconceived notion does not a persuasive case make.

Cohn’s analysis relied on just two data points: pre-election polls archived at the Roper Center for the 2012 and 2020 presidential elections. Cohn tried to make it seem more elaborate by noting that his analysis relied on “thousands of survey interviews.” That could mean just two polls, or an average of several polls from 2012 and 2020, which would indeed include thousands of respondents. But the limiting factor is that it’s still just two data points. Cohn excluded the 2016 presidential election, and ignored altogether any voting contests other than the two presidential elections. To call it superficial is to be kind.

Had he compared instead, say, the 2016 election with 2020, it’s likely his conclusions would have been reversed. Biden’s popular vote margin was more than twice as large as Clinton’s, which suggests that in the interim, most age groups had either moved toward the Democratic Party or remained static.

Clarifying the analysis

Asked in a follow-up column (6/14/23) if it's just about Obama being more popular among young people than Biden, Cohn says, "With this data, it’s hard to know." Yes, that's the problem of only comparing two points! He does acknowledge that John Kerry in 2004 did slightly worse than Obama and slightly better than Biden with older Millennials.

Two weeks after his millennial article, Cohn (New York Times, 6/14/23) implicitly acknowledged that the folklore he cited earlier didn’t apply to older voters. Some of his readers had asked the obvious question: How did Biden do better in 2020 than Obama in 2012 if all those cohorts of voters under 50 shifted toward the Republican Party in 2020? After all, Biden received 51.3% of the vote to Trump’s 46.8%, a 4.5 point margin. Obama won by 51.1% to 47.2%, a difference of 3.9 points.

Lo and behold, it turns out that one factor explaining Biden’s better performance was antithetical to the conventional wisdom. Cohn explained:

Mr. Biden fared much better than Mr. Obama among voters born before 1960—those who were at least 60 years old in 2020 or 52 in 2012. These cohorts lurched to the left between 2012 and 2016, and yet again between 2016 and 2020.

Lurching to the left is not what that “oldest rule in politics,” or “folklore,” predicts older voters would do. Older people aren’t supposed to lose their brains as they age, and revert to having only a heart.

How is it that Cohn did not alert the reader to that inconsistency in his original article? “Because of the scope of the article,” he wrote, “we didn’t show every age cohort.” Essentially, the left-lurching oldsters did not fit the preconceived theme like the right-sliding youngsters. So…leave them out of the analysis.

What Cohn’s findings revealed was not some perennial pattern in American politics, but rather an unusual change over one time period—when younger voters tended to switch toward the Republican presidential candidate, and older voters were more likely to switch to the Democratic candidate. By itself, without any context, this observation hardly provides us any useful information.

A 50-year study

The notion that liberal young people become conservative old people is at best a vague prediction. What, after all, does it mean to be liberal or conservative?

The underlying assumption in Cohn’s (and Burn-Murdoch’s) pieces is that the Democratic and Republican parties provide the liberal-to-conservative spectrum that undergirds the folk saying. But there are many other measures that seem more relevant to what it means to be liberal and conservative than voting choices between two dominant political parties.

In most political issues polled over 50 years, opinion has trended in a progressive direction for all age cohorts (Public Opinion Quarterly, Winter/21).

Two years ago, Michael Hout, a New York University sociologist, published a report in Public Opinion Quarterly (Winter/21) that examined US attitudes and behavior on a wide variety of measures, including questions on race, gender, sexuality and personal liberty. Data came from the General Social Survey (GSS), which has been conducting national surveys of Americans since 1972. As the news release from NYU (12/9/21) noted:

Americans’ attitudes and behaviors have become more liberal overall in the past 50 years, and have taken a decidedly liberal tilt since the 1990s....

Hout considered [283] variables—attitudes, beliefs and behaviors—from 1972 to 2018 and the age of the respondents by dividing them into 32 cohorts, each spaced two to three years apart. The analysis included Americans born as early as 1882 and as late as 2000.

Overall, the data showed that each cohort is more liberal, on balance, than the one that came before it. Specifically, 62% of variables analyzed were more liberal in the more recent birth cohorts than they were in the oldest ones, relative to when a particular attitude or belief was measured by the survey; by contrast, only 5% were more conservative.

Moreover, each cohort itself became more liberal during the studied period. Within cohorts, recent measurements—those within the last decade—were more liberal than in last three decades of the 20th century in 48% of the variables, and more conservative in only 11% (Note: The rest of the variables either had no political lean [e.g., the importance of getting along with co-workers] or did not change [e.g., views on abortion and gun control]).

More liberal with age

Looking at survey results over time debunks the notion that the views of each generation shifts to the right over time. (CC photo: lacitadelle)

Perhaps the most interesting finding relating to the political folklore that people become more conservative as they age is in the observation that within cohorts—each age group of two to three years—people became more liberal over time with 48% of the questions asked, and more conservative with just 11%.

But if Americans are becoming more liberal, why are Republicans continually competitive with Democrats? The short answer is that, as Hout notes, “many of the liberal trends in the GSS are not factors in elections.”

Parties choose the issues they run on, avoiding those where a widespread consensus exists. Republicans no longer run (at least directly) on opposition to gay marriage, for example, given the progressive trend on this issue. Nor are most Republicans explicitly proposing racial segregation in housing or schools, or demanding that women remain in the home—all of which are issues where public opinion has moved sharply to the left.

Along with suggesting a more expansive definition of political labels, the main value of Hout's study is to debunk the notion that there is some inherent tendency for people to become more conservative as they age. If anything, the data suggest that over the previous half century, most Americans have become more liberal with age—at least as measured by the many attitudes, beliefs and behaviors surveyed by the GSS.

No one knows if that trend might change over the next 50 years. But one thing is for certain: It’s time to put that old folklore to rest.

ACTION ALERT: You can send a message to the New York Times at [email protected] (Twitter: @NYTimes). Please remember that respectful communication is the most effective. Feel free to leave a copy of your communication in the comments thread.

|