| From | Critical State <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Loss at Sea |

| Date | June 21, 2023 6:47 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Read about the curious case of cartels that are not cartels. Received this from a friend? SUBSCRIBE [[link removed]] CRITICAL STATE Your weekly foreign policy fix. If you read just one thing …

… read about the curious case of cartels that are not cartels.

In Mexico, which had drug crackdowns before the United States, the War on Drugs is plausibly a way for the government to manage illicit trade, rather than trying to stop it. That’s one thesis of “ Do Cartels Exist [[link removed]]?,” in which Rachel Nola reviews two books for Harper’s Magazine on the interconnected topic of drug trafficking and violence. In “Drug Cartels Do Not Exist: Narcotrafficking in US and Mexican Culture,” by Oswaldo Zavala, translated by William Savinar, the author argues that cartels are an invented villain, covering up what is really a relationship between police, politicians, and traffickers. Nolan pairs this review with “The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade,” by Benjamin T. Smith, which adds depth. “Still,” writes Nolan, “from the perspective of the Colombian, Mexican, and US governments, it makes more sense to say you are going after the leader of a group rather than plucking important people out of a swirling mess while leaving the mess more or less intact.” Later, she concludes, even if “you believe that drug traffickers do control extensive territory and supply chains, they shouldn’t be called cartels. If there were a true cartel, operations would be centralized, and there would be less violence.”

depth charges

At the time of this writing, Canada used a submarine-hunting plane, as well as sonar buoys and surface ships, to search for a lost recreational submarine [[link removed]] off the coast of Newfoundland. The extraordinary effort, with aid from the United States, matches the high profile of the reported loss, though not the ultimate scale of lives lost at sea.

“On June 14, what was likely the second-deadliest refugee and migrant shipwreck on record occurred when a boat carrying as many as 800 migrants sank off the Greek coast [[link removed]]. Greek authorities had tracked the vessel and early signs suggest the country’s coast guard was slow to act [[link removed]] despite numerous warning signs,” writes [[link removed]] Alex Shepard in The New Republic.

The contrast Shepard draws is sharp on every level: the passengers of the lost deep sea submarine are tourists who paid exorbitantly for the privilege of potentially getting entombed in a vessel that was built to deliberately skirt safety standards. By contrast, the migrants lost at sea should be eminently more sympathetic, even if limited to their choice of a dry land destination and safety. If we are to invest in saving lives at sea, the lost migrants could have been saved with a far more modest effort. “There’s greater appetite for coverage of lifestyles of the rich and (now) famous than for the deaths of hundreds of anonymous migrants, or at least cable news assignment editors think so,” bemoans [[link removed]] Shepard.

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] blog of war

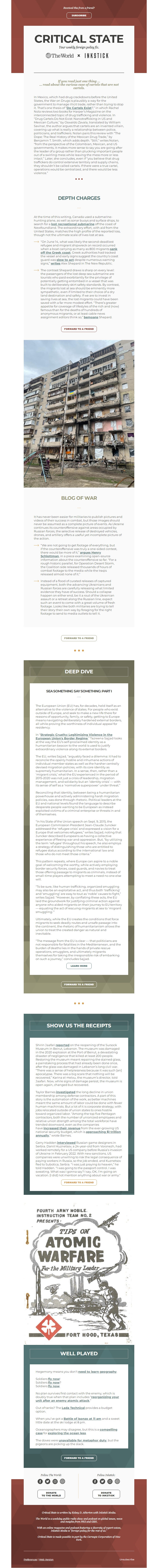

It has never been easier for militaries to publish pictures and videos of their success in combat, but those images should never be assumed as a complete picture of events. As Ukraine continues its counteroffensive against areas occupied by Russian forces, the selective release of destroyed vehicles, drones, and artillery offers a useful yet incomplete picture of the action.

“We are not going to get footage of everything, but if the counteroffensive was truly a one-sided contest, there would be more of it,” argues Henry Schlottman [[link removed]], in a piece examining open-source information about the counteroffensive so far. “For a rough historic parallel, for Operation Desert Storm, the Coalition side released thousands of hours of combat footage to the media while the Iraqis released almost none of it.”

Instead of a flood of curated releases of captured equipment, both the advancing Ukrainians and Russian forces are carefully releasing what limited evidence they have of success. Should a collapse happen on either end, be it a rout of the Ukrainian assault or a retreat along the Russian line, expect such an event to come with a great volume of fresh footage. Looks like both militaries are trying to tell their story their own way by foraging for the right footage to send to media outlets to tell it.

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] DEEP DIVE Sea Something Say Something: Part I

The European Union (EU) has, for decades, held itself as an alternative to the violence of states. For people who exist outside of Europe, and seek to make a new life there for reasons of opportunity, family, or safety, getting to Europe means navigating deliberately hardened external borders, all while proving the worthiness of individual appeal for residency.

In “ Strategic Cruelty: Legitimizing Violence in the European Union's Border Regime [[link removed]],” Tazreena Sajjad looks at the way the EU’s self-proclaimed identity as a humanitarian beacon to the world is used to justify extraordinary violence along its external borders.

The EU, writes Sajjad, “arguably faced a dilemma: it had to reconcile the openly hostile and inhumane actions of individual member states as well as the harsher centrally devised migration policies, with its core identity as supremely humanitarian. In a sense, then, rather than a ‘migrant crisis,’ what the EU experienced in the period of 2015-2020 was not just a crisis of leadership, migration management, and solidarity but an ‘identity crisis’ — with its sense of self as a ‘normative superpower’ under threat.”

Reconciling that identity, between being a humanitarian powerhouse and actively administering harsh migration policies, was done through rhetoric. Political leaders at the EU and national levels found the language to describe desperate people wanting to be European as instead exploited victims of a criminal enterprise or threats in and of themselves.

“In his State of the Union speech on Sept. 9, 2015, the European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker addressed the ‘refugee crisis’ and expressed a vision for a Europe that welcomes refugees,” writes Sajjad, noting that Juncker described Europeans as having a collective experience of fleeing war and oppression. But, “by utilizing the term ‘refugee’ throughout his speech, he also employs a strategy of distinguishing those who are entitled to refugee status according to the international law and those who do not meet those criteria.”

This pattern repeats, where Europe can aspire to a noble goal of welcoming the worthy, while actively employing border security forces, coast guards, and navies to treat those offering passage to migrants as criminals, instead of small-time players attempting to meet a need no one else will.

“To be sure, like human trafficking, organized smuggling may also be an exploitative act, and thus both ‘trafficking’ and ‘smuggling’ are easy to tout as ‘noble’ causes to fight,” writes Sajjad. “However, by conflating these acts, the EU laid the groundwork for justifying criminal action against anyone who aided migrants on their journey to EU territory — equating the act of rescuing migrants at sea to ‘migrant smuggling.’”

Ultimately, while the EU creates the conditions that force migrants to seek deadly routes and unsafe passage into the continent, the rhetoric of humanitarianism allows the union to treat the created danger as natural and inevitable.

“The message from the EU is clear — that politicians are not responsible for fatalities in the Mediterranean, and the burden of deaths lies in the hands of private rescue operations, smugglers, and ultimately migrants themselves for taking the irresponsible risk of embarking on such a journey,” concludes Sajjad.

LEARN MORE [[link removed]]

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] SHOW US THE RECEIPTS

Shirin Jaafari reported [[link removed]] on the reopening of the Sursock Museum in Beirut, Lebanon. The museum was damaged in the 2020 explosion at the Port of Beirut, a devastating disaster of negligence that killed at least 200 people. Restoring the museum meant repairing the stained glass, a painstaking process that had already been done once, after the glass was damaged in Lebanon’s long civil war. “There was a sense of helplessness because it was such [an] apocalypse. There was a big scare that nothing will be recovered,” Karina el-Helou, the museum’s director, told Jaafari. Now, while signs of damage persist, the museum is open again, changed but recovered.

Taylor Barnes investigated [[link removed]] the long decline in union membership among defense contractors. A part of this story is the automation of the work, as better machines meant the same amount of labor could be done with fewer human machinists. But a lot of it is corporate strategy, with jobs relocated outside of union states to ones hostile toward organized labor. “Among the top five Pentagon contractors, both the number of unionized employees and relative union strength among the total workforce have trended downward, even as the companies have increased their revenue [[link removed]] from the ever-growing US national security budget, which is approaching $1 trillion annually [[link removed]],” wrote Barnes.

Gerry Hadden interviewed [[link removed]] Russian game designers in Serbia. Daniil Kuznetsov, a 24-year-old from Voronezh, had worked remotely for a US company before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. With new sanctions, US companies were unwilling to risk the legal consequence of paying workers in Russia, so the job ended, and Kuznetsov fled to Subotica, Serbia. “I was just praying to heaven,” he told Hadden. “I was going to the passport control. I was sweating. What was I gonna say? I say, OK, I’m going on vacation. [I did] not mention anything about war or army."

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] WELL PLAYED

Hegemony means you don’t need to learn geography [[link removed]].

Soldiers fly now [[link removed]]!

Soldiers fly now [[link removed]]?

Soldiers fly now [[link removed]].

No plan survives first contact with the enemy, which is doubly true when that plan includes “ reorganizing your unit after an enemy atomic attack [[link removed]].”

Out of tanks? The Lada Technical [[link removed]] provides a budget option.

When you’ve got a Battle of Isonzo at 11 am [[link removed]] and a sweet little date at the ski lodge at 8 pm.

Oceanographers may disagree, but this is a compelling case [[link removed]] for exploring the ocean less [[link removed]].

The doves were unavailable for metaphor duty [[link removed]], but the pigeons are picking up the slack.

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] Follow The World: DONATE TO THE WORLD [[link removed]] Follow Inkstick: DONATE TO INKSTICK [[link removed]]

Critical State is written by Kelsey D. Atherton with Inkstick Media.

The World is a weekday public radio show and podcast on global issues, news and insights from PRX and GBH.

With an online magazine and podcast featuring a diversity of expert voices, Inkstick Media is “foreign policy for the rest of us.”

Critical State is made possible in part by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Preferences [link removed] | Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed]

… read about the curious case of cartels that are not cartels.

In Mexico, which had drug crackdowns before the United States, the War on Drugs is plausibly a way for the government to manage illicit trade, rather than trying to stop it. That’s one thesis of “ Do Cartels Exist [[link removed]]?,” in which Rachel Nola reviews two books for Harper’s Magazine on the interconnected topic of drug trafficking and violence. In “Drug Cartels Do Not Exist: Narcotrafficking in US and Mexican Culture,” by Oswaldo Zavala, translated by William Savinar, the author argues that cartels are an invented villain, covering up what is really a relationship between police, politicians, and traffickers. Nolan pairs this review with “The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade,” by Benjamin T. Smith, which adds depth. “Still,” writes Nolan, “from the perspective of the Colombian, Mexican, and US governments, it makes more sense to say you are going after the leader of a group rather than plucking important people out of a swirling mess while leaving the mess more or less intact.” Later, she concludes, even if “you believe that drug traffickers do control extensive territory and supply chains, they shouldn’t be called cartels. If there were a true cartel, operations would be centralized, and there would be less violence.”

depth charges

At the time of this writing, Canada used a submarine-hunting plane, as well as sonar buoys and surface ships, to search for a lost recreational submarine [[link removed]] off the coast of Newfoundland. The extraordinary effort, with aid from the United States, matches the high profile of the reported loss, though not the ultimate scale of lives lost at sea.

“On June 14, what was likely the second-deadliest refugee and migrant shipwreck on record occurred when a boat carrying as many as 800 migrants sank off the Greek coast [[link removed]]. Greek authorities had tracked the vessel and early signs suggest the country’s coast guard was slow to act [[link removed]] despite numerous warning signs,” writes [[link removed]] Alex Shepard in The New Republic.

The contrast Shepard draws is sharp on every level: the passengers of the lost deep sea submarine are tourists who paid exorbitantly for the privilege of potentially getting entombed in a vessel that was built to deliberately skirt safety standards. By contrast, the migrants lost at sea should be eminently more sympathetic, even if limited to their choice of a dry land destination and safety. If we are to invest in saving lives at sea, the lost migrants could have been saved with a far more modest effort. “There’s greater appetite for coverage of lifestyles of the rich and (now) famous than for the deaths of hundreds of anonymous migrants, or at least cable news assignment editors think so,” bemoans [[link removed]] Shepard.

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] blog of war

It has never been easier for militaries to publish pictures and videos of their success in combat, but those images should never be assumed as a complete picture of events. As Ukraine continues its counteroffensive against areas occupied by Russian forces, the selective release of destroyed vehicles, drones, and artillery offers a useful yet incomplete picture of the action.

“We are not going to get footage of everything, but if the counteroffensive was truly a one-sided contest, there would be more of it,” argues Henry Schlottman [[link removed]], in a piece examining open-source information about the counteroffensive so far. “For a rough historic parallel, for Operation Desert Storm, the Coalition side released thousands of hours of combat footage to the media while the Iraqis released almost none of it.”

Instead of a flood of curated releases of captured equipment, both the advancing Ukrainians and Russian forces are carefully releasing what limited evidence they have of success. Should a collapse happen on either end, be it a rout of the Ukrainian assault or a retreat along the Russian line, expect such an event to come with a great volume of fresh footage. Looks like both militaries are trying to tell their story their own way by foraging for the right footage to send to media outlets to tell it.

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] DEEP DIVE Sea Something Say Something: Part I

The European Union (EU) has, for decades, held itself as an alternative to the violence of states. For people who exist outside of Europe, and seek to make a new life there for reasons of opportunity, family, or safety, getting to Europe means navigating deliberately hardened external borders, all while proving the worthiness of individual appeal for residency.

In “ Strategic Cruelty: Legitimizing Violence in the European Union's Border Regime [[link removed]],” Tazreena Sajjad looks at the way the EU’s self-proclaimed identity as a humanitarian beacon to the world is used to justify extraordinary violence along its external borders.

The EU, writes Sajjad, “arguably faced a dilemma: it had to reconcile the openly hostile and inhumane actions of individual member states as well as the harsher centrally devised migration policies, with its core identity as supremely humanitarian. In a sense, then, rather than a ‘migrant crisis,’ what the EU experienced in the period of 2015-2020 was not just a crisis of leadership, migration management, and solidarity but an ‘identity crisis’ — with its sense of self as a ‘normative superpower’ under threat.”

Reconciling that identity, between being a humanitarian powerhouse and actively administering harsh migration policies, was done through rhetoric. Political leaders at the EU and national levels found the language to describe desperate people wanting to be European as instead exploited victims of a criminal enterprise or threats in and of themselves.

“In his State of the Union speech on Sept. 9, 2015, the European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker addressed the ‘refugee crisis’ and expressed a vision for a Europe that welcomes refugees,” writes Sajjad, noting that Juncker described Europeans as having a collective experience of fleeing war and oppression. But, “by utilizing the term ‘refugee’ throughout his speech, he also employs a strategy of distinguishing those who are entitled to refugee status according to the international law and those who do not meet those criteria.”

This pattern repeats, where Europe can aspire to a noble goal of welcoming the worthy, while actively employing border security forces, coast guards, and navies to treat those offering passage to migrants as criminals, instead of small-time players attempting to meet a need no one else will.

“To be sure, like human trafficking, organized smuggling may also be an exploitative act, and thus both ‘trafficking’ and ‘smuggling’ are easy to tout as ‘noble’ causes to fight,” writes Sajjad. “However, by conflating these acts, the EU laid the groundwork for justifying criminal action against anyone who aided migrants on their journey to EU territory — equating the act of rescuing migrants at sea to ‘migrant smuggling.’”

Ultimately, while the EU creates the conditions that force migrants to seek deadly routes and unsafe passage into the continent, the rhetoric of humanitarianism allows the union to treat the created danger as natural and inevitable.

“The message from the EU is clear — that politicians are not responsible for fatalities in the Mediterranean, and the burden of deaths lies in the hands of private rescue operations, smugglers, and ultimately migrants themselves for taking the irresponsible risk of embarking on such a journey,” concludes Sajjad.

LEARN MORE [[link removed]]

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] SHOW US THE RECEIPTS

Shirin Jaafari reported [[link removed]] on the reopening of the Sursock Museum in Beirut, Lebanon. The museum was damaged in the 2020 explosion at the Port of Beirut, a devastating disaster of negligence that killed at least 200 people. Restoring the museum meant repairing the stained glass, a painstaking process that had already been done once, after the glass was damaged in Lebanon’s long civil war. “There was a sense of helplessness because it was such [an] apocalypse. There was a big scare that nothing will be recovered,” Karina el-Helou, the museum’s director, told Jaafari. Now, while signs of damage persist, the museum is open again, changed but recovered.

Taylor Barnes investigated [[link removed]] the long decline in union membership among defense contractors. A part of this story is the automation of the work, as better machines meant the same amount of labor could be done with fewer human machinists. But a lot of it is corporate strategy, with jobs relocated outside of union states to ones hostile toward organized labor. “Among the top five Pentagon contractors, both the number of unionized employees and relative union strength among the total workforce have trended downward, even as the companies have increased their revenue [[link removed]] from the ever-growing US national security budget, which is approaching $1 trillion annually [[link removed]],” wrote Barnes.

Gerry Hadden interviewed [[link removed]] Russian game designers in Serbia. Daniil Kuznetsov, a 24-year-old from Voronezh, had worked remotely for a US company before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. With new sanctions, US companies were unwilling to risk the legal consequence of paying workers in Russia, so the job ended, and Kuznetsov fled to Subotica, Serbia. “I was just praying to heaven,” he told Hadden. “I was going to the passport control. I was sweating. What was I gonna say? I say, OK, I’m going on vacation. [I did] not mention anything about war or army."

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] WELL PLAYED

Hegemony means you don’t need to learn geography [[link removed]].

Soldiers fly now [[link removed]]!

Soldiers fly now [[link removed]]?

Soldiers fly now [[link removed]].

No plan survives first contact with the enemy, which is doubly true when that plan includes “ reorganizing your unit after an enemy atomic attack [[link removed]].”

Out of tanks? The Lada Technical [[link removed]] provides a budget option.

When you’ve got a Battle of Isonzo at 11 am [[link removed]] and a sweet little date at the ski lodge at 8 pm.

Oceanographers may disagree, but this is a compelling case [[link removed]] for exploring the ocean less [[link removed]].

The doves were unavailable for metaphor duty [[link removed]], but the pigeons are picking up the slack.

FORWARD TO A FRIEND [[link removed]] Follow The World: DONATE TO THE WORLD [[link removed]] Follow Inkstick: DONATE TO INKSTICK [[link removed]]

Critical State is written by Kelsey D. Atherton with Inkstick Media.

The World is a weekday public radio show and podcast on global issues, news and insights from PRX and GBH.

With an online magazine and podcast featuring a diversity of expert voices, Inkstick Media is “foreign policy for the rest of us.”

Critical State is made possible in part by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Preferences [link removed] | Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Public Radio International

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor